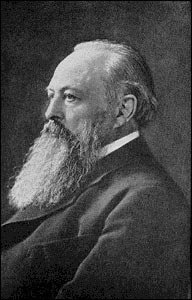

John Emerich Edward Dalberg Acton—First Baron Acton of Aldenham—was born in Naples, Italy on January 10, 1834. His father, Sir Richard Acton, was descended from an established English line, and his mother, Countess Marie Louise de Dalberg, came from a Rhenish family which was considered to be second in status only to the imperial family of Germany. Three years after his father's death in 1837, his mother remarried Lord George Leveson (later known as Earl Granville, William Gladstone's Foreign Secretary), and moved the family to Britain. With his cosmopolitan background and upbringing, Acton was equally at home in England or on the Continent, and grew up speaking English, German, French, and Italian.

John Emerich Edward Dalberg Acton—First Baron Acton of Aldenham—was born in Naples, Italy on January 10, 1834. His father, Sir Richard Acton, was descended from an established English line, and his mother, Countess Marie Louise de Dalberg, came from a Rhenish family which was considered to be second in status only to the imperial family of Germany. Three years after his father's death in 1837, his mother remarried Lord George Leveson (later known as Earl Granville, William Gladstone's Foreign Secretary), and moved the family to Britain. With his cosmopolitan background and upbringing, Acton was equally at home in England or on the Continent, and grew up speaking English, German, French, and Italian.

Barred from attending Cambridge University because of his Catholicism, John Acton studied at the University of Munich under the famous church historian, Ignaz von Döllinger. Through Döllinger's teaching, Acton learned to consider himself first and foremost a historian. Early in life, he nurtured a great fondness for Whig politicians such as Edmund Burke, but Acton soon became a Liberal. His time with Döllinger also broadened his appreciation and understanding of Catholic and Reformed theology. Through his studies and his own experience, Acton was made acutely aware of the danger posed to individual conscience by any kind of religious or political persecution.

Through the influence of his stepfather, Acton pursued electoral politics and entered the House of Commons in 1859 as a member for the Irish constituency of Carlow. In 1869, Gladstone rewarded Acton for his efforts on behalf of Liberal political causes by offering him a peerage.

Earlier, Lord Acton also acquired the Rambler, making it a liberal Catholic journal dedicated to the discussion of social, political, and theological issues and ideas. Through this activity and through his involvement in the first Vatican Council, Lord Acton became known as one of the most articulate defenders of religious and political freedom. He argued that the church faithfully fulfills its mission by encouraging the pursuit of scientific, historical, and philosophical truth, and by promoting individual liberty in the political realm.

The 1870s and 1880s saw the continued development of Lord Acton's thought on the relationship between history, religion, and liberty. In that period he began to construct outlines for a universal history designed to document the progress of the relationship between religious virtue and personal freedom. Acton spoke of his work as a “theodicy,” a defense of God's goodness and providential care of the world.

In 1895, Lord Acton was appointed Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge University. From this position, he deepened his view that the historian's search for truth entails the obligation to make moral judgments on history, even when those judgments challenge the historian's own deeply held opinions. Although he never finished his anticipated universal history, Lord Acton planned the Cambridge Modern History and lectured on the French Revolution, Western history since the Renaissance, and the history of freedom from antiquity through the 19th century.

When he died in 1902, Lord Acton was considered one of the most learned people of his age, unmatched for the breadth, depth, and humanity of his knowledge. He has become famous to succeeding generations for his observation —learned through many years of study and first-hand experience—that “power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”