Your book, The Forgotten Man, has played a major role in challenging the consensus about the New Deal that prevails in the academy and in popular culture. I'm interested in what motivated you to write the book.

We grew up with various versions of the 1930s. One version was that Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office and made it better. That Roosevelt cured the depression, in essence. A less simple version was: Roosevelt didn't cure our economic ailment in the 1930s, but that didn't matter because he gave us back our confidence. Another version said the Depression was caused by monetary problems and the rest doesn't matter. That the Depression was about monetary problems the way the play Hamlet is about a prince – there's no play without the prince. That's the version that markets-oriented people grew up with, following Milton Friedman. I'm not sure if Friedman over the course of his life meant the message to be quite so exclusive of other factors, but that was the message as it was received. When I was working on the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal, I thought maybe I should look into this more because lots of things happened in the 1930s, in addition to monetary events. Writing editorials or columns as I did later, you bump into these edifices—The Wagner Act, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Many of them were erected during the New Deal period. Maybe it was time to look at them. And also it came to me, that we were becoming a culture where we believed in eternal prosperity, and that couldn't last. It couldn't be right. Roosevelt said the only thing we have to fear is fear itself. The economist John Lipsky once said some time early in this decade that the only thing we had to fear was the lack of fear itself. That made sense to me. So maybe it would be worthwhile to go back and look at the time when we didn't have prosperity, and look at what caused the Depression to endure so long.

Amity Shlaes in Brooklyn.

In The Forgotten Man, you talk about the Depression within the Depression, especially in the years of 1937 and 1938. What happened?

The Forgotten Man starts with the story of a boy named William Troeller who hangs himself rather than asking for food. In some of the accounts it even says that he ate two grapes and then he hung himself, rather than ask for food. And the striking thing was that this did not happen early in the depression. This did not happen in the England of Dickens, or in the United States at the beginning of the Great Depression. This happened rather in 1937 or 1938. So that was news, that the Depression within the Depression was so bad, and it seemed important. The recovery disappeared or, to put it more precisely, the recovery chose to stay away. Industrial production went down more than 60 percent. Non-durable production slowed. The stock market dropped. The stock market prices fell 40 percent, and then they fell another 10 percent. The unemployment rate went way up. By some measures it went from around 12 percent up towards 20 percent. So what's happening? Gene Smiley, who was a professor at Marquette, details this factually in his crucial book, Rethinking the Great Depression. Some of these factors had to do with a new sense of a caution. The government was afraid of inflation. So policy was often "too tight." Washington was also afraid that banks would fail. So it said banks especially should have more reserve so that they'll pass all the stress tests, to put it in modern language. And the banking act of 1935 gave the feds the authority to raise reserve requirements. Federal authorities said, this won't matter, and it won't be contraction because the banks have already accumulated lots of reserves now—they are concerned about a repeat of the early 1930s. The point is they wanted a great cushion between them and failure. But what did the banks do when the government increased requirements? They took it as a signal to accumulate yet more reserves. So it's like you pay someone to put their seatbelt on and they already have their seatbelt on. Well they put on a second seatbelt. What else kept recovery away? High labor costs. This was a fact that was discussed thoroughly at the time, but less since. We think that the Wagner Act, which is our great labor law of 1935, is benign and good. But in fact, it gave John L. Lewis, the great labor leader, the authority to bully, which he did, and wages went up higher than companies could afford. And therefore, companies had more trouble. The Forgotten Man is a narrative book, but there are two economists who document this labor cost disadvantage thoroughly and technically. One is Harold Cole at University of Pennsylvania, and the other is his partner, Lee Ohanian at UCLA. Ohanian recently noted in Senate testimony that total hours worked per hour were 20 percent below their 1929 level at the end of the 1930s. So, wow, they made labor more expensive during a downturn and thereby increased unemployment. This was the decade that lived the phrase "nice work if you can get it."

How much has Depression-era literature, such as John Steinbeck's, The Grapes of Wrath, shaped our views of the New Deal?

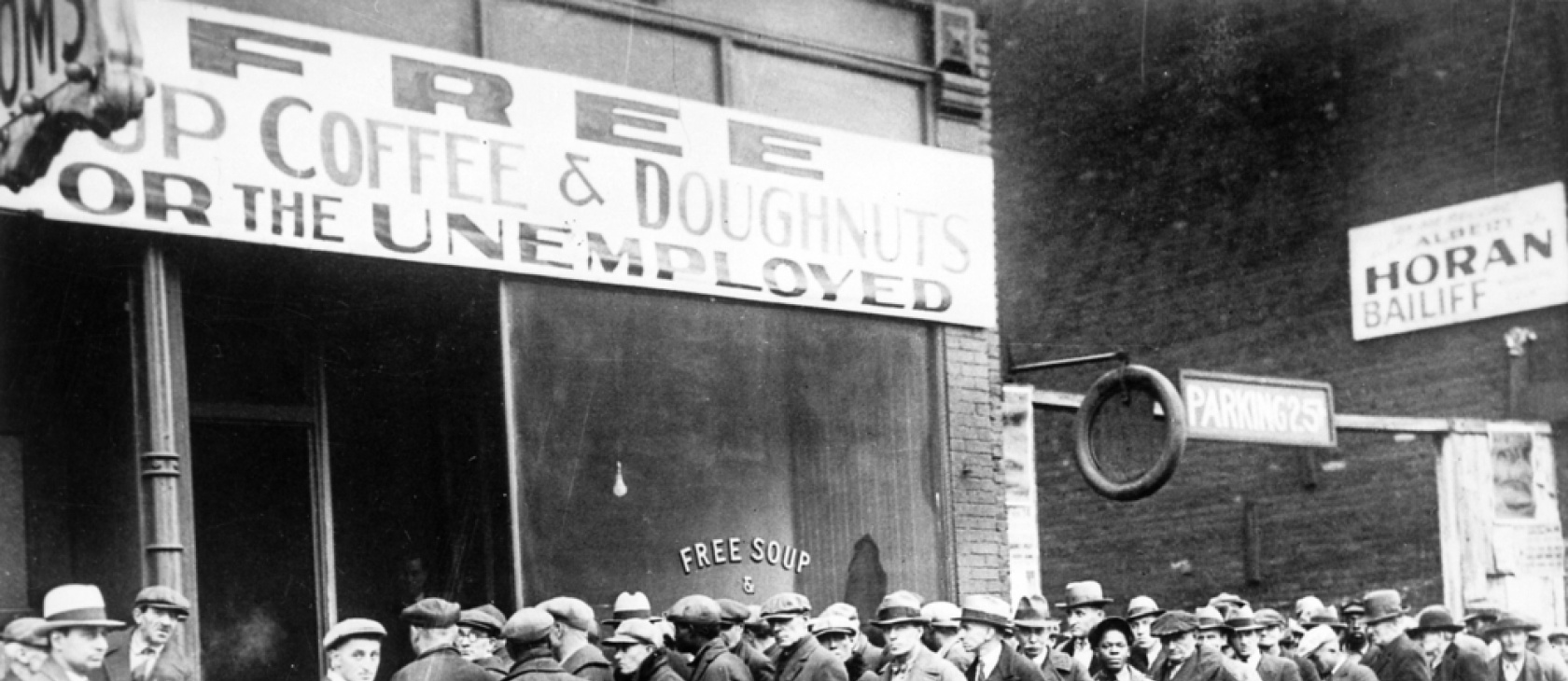

New York after the bank failures during the Great Depression.

Art shapes what we think. And the art of the period was powerful. John Steinbeck's writing or the photos taken by famous photographers like Dorothea Lange who took the picture of the Migrant Mother, these are the type of photos that we continue to study. We think of these as holy documents, holy artifacts. When viewers look at Migrant Mother, they think they were looking at an image that was made for Life Magazine. But that's putting a modern spin on history. The reality was that Migrant Mother was photographed for the government—the Farm Security Administration. Such pictures were representing true poverty, but they also had a propagandistic side. Roy Stryker, who ran the photography project that yielded such images, later spelled this all out. He wrote about the specific political goals of the photography project: his department "could not afford to hammer home anything except their message that federal money was desperately needed for major relief programs. Most of what the photographers had to do to stay on the payroll was routine stuff to show what a good job the agencies were doing in the field." What's the takeaway? We know the Depression was terrible. But we want to be quite discerning in investigating the causes of it and that's the area where we've been a little too emotional.

Is there anything we can learn from Calvin Coolidge today about a good and positive way to respond to the economic crisis, whether on a personal or governmental level? Are his views even relevant in approaching the post—New Deal, post—Great Society era?

I'm at work on a biography of Coolidge and am fortunate to have the support of the Calvin Coolidge Memorial Foundation. Coolidge definitely would have responded differently to these crises. He had his own Hurricane Katrina, the 1927 flood of the Mississippi, and he didn't go down to see the damage or supervise recovery. He thought it was inappropriate. He sent his commerce secretary. Coolidge didn't like public sector unions to strike. He was the governor who did an early version of Reagan's clash with the air traffic controllers, quite dramatically. Coolidge fired the Boston police when they struck in 1919. Coolidge believed in smaller government. He cut taxes a number of times. Overall in the 1920s, taxes were cut five times by Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon. Coolidge called Herbert Hoover, whom he saw as an activist, "Wonderboy." Coolidge didn't understand Roosevelt. In fact, he said as much right towards the end. Coolidge died after Roosevelt's election, but before his inauguration he said "I feel I no longer fit in with these times." So I think the country would have gone much differently. There were many, many factors driving the Depression, especially early on. We can't say Roosevelt broke it, or Hoover broke it, or Coolidge would have fixed it. That's a little simple, but Coolidge was a withholder and a refrainer.

We always seem to hear so much about the federal programs and New Deal in the 1930s, but how did private charities and churches respond? Did they wither or flourish?

In The Forgotten Man there are several examples of private charities endeavoring to make an effort during the New Deal and feeling squeezed by the New Deal. Father Divine, the black cult leader, wrote to the Roosevelt administration saying that he felt some of the programs were disturbing the work ethic of his constituents. So it's clear that these charities, and more important, the fraternal societies that did so much work in the United States, felt squeezed. Professor David T. Beito effectively showed the relationship between emerging welfare states and the decline of fraternal services. So, was there crowding out? Probably. Beito documents that well. And when the government provided, the fraternal societies no longer felt the need to. And one has the sense that people turned to government rather than to such societies.

How does faith figure into The Forgotten Man?

I tried to portray faith and fraternalism, and also other self-help innovations. And I was happy with the self-help innovation I was able to cover, which was the creation of Alcoholics Anonymous by Bill Wilson. That's an innovation that's remained today. We all belong to some kind of self-help group, whether it's a chat discussion about our bunion, or a discussion group for the grandparent or parent of a two year old. So I was able to convey that through Wilson, how he popularized that format. And then I thought to have a religious figure, it ended up being Father Divine who was in New York, and he's a large presence. He's a black leader. There are hundreds of stories about him in New York in the 1930s in the papers. He believed in property. His gospel of plenty was in opposition to the gospel of scarcity preached by the New Deal most of the time. Roosevelt believed that our economic frontier was reached. And he said as much in his speeches. One stunning thing about Father Divine was that he actually dared to joust with Roosevelt. FDR had a house on the Hudson River, and Father Divine acquired property just on the other side, in order to be in FDR's face about an issue that was important to him and to all of us, which is the failure of the New Dealers to stop lynching. Father Divine thought that if Roosevelt could fool around with the Constitution in other areas, he might fool around in the area of civil rights to halt lynching. And that action between Father Divine and FDR was quite compelling and fun to convey in The Forgotten Man.

Shlaes talks about the current recession on FOX news.

But I didn't really get to the Catholic Church. I didn't get to a lot of other churches. In retrospect I think Father Divine is a bit questionable as an exclusive choice to represent the faith because he was a cult teacher. He believed he was God. He's not someone most churches would be proud of for that reason or select as their representative. It's sort of a mockery of their faith. And in that sense, I should have had someone else in addition, along with Father Divine. What I tried to get at in the book was that in the secular vacuum the government came to take the place of the church.

In the midst of this current economic crisis, what kind of warning can you offer young people about the changes they are likely to face, such as their own tax burden and their retirement? How is the current expansion of government likely to impact their daily lives?

The forgotten man in The Forgotten Man book was that person who endured the Great Depression, and whom the New Deal did not help. This is the person who didn't happen to be in one of the constituent groups whom Roosevelt sought out and connected with, or whom Hoover sought out and connected with. The forgotten man today would be the person who isn't remembered by lawmakers this go-round. First of all, that individual would be the man or woman who paid their mortgage and now is going to lose his job and find it harder to continue to pay the mortgage because others did not pay theirs. Everybody has sympathy for the latter party. We know how hard it is to meet a mortgage, but we also are not sure whether one party should suffer for that other party's failure. In addition, our own children and grandchildren are forgotten men because they will pay the taxes in the future that will result from our overexpansion today.

What do you like most about America? Are you optimistic about its future?

Resilience is our abiding characteristic. We don't get mired and we change a lot. We're proud in a good way. You can think of market recovery in terms of rock climbing. Equities people always say of the stock market "the market climbs a wall of worry." But you can also say that "the market wants to go up, and the only question is, what is stopping it"? The economy wants to recover now. It's our job now to figure out what is stopping it and reduce the scale of that obstacle. So we don't know what America will be like. We don't know what kind of inventions will come. Also, the forgiving quality of the United States is crucial. You can make an error and start over and that is represented in our bankruptcy law. In the olden days when people went into debt on the East Coast, they'd head west. Did they drop the keys in the mailbox of the bank? They did the equivalent. Was it right? Not particularly but it also reflected energy. There's always a trade off between risk taking and prudence, and honoring the law and the contract. Anyhow this idea that people are throwing keys into the mailbox or dropping them off at the bank and leaving, this idea that that will mean the ruin of the United States is, perhaps, exaggerated. It's happened before and we've still had prosperity. The prosperity can only happen if property rights over the longer term do get honored.