Greetings from Kraków, where I’ve just attended an Acton co-sponsored event on “Europe between post-Enlightenment nihilism and the Islamic question” at the Pontifical University John Paul II.

Dealing with this ponderous subject were some very accomplished scholars: Prof. Francesco Botturi of the Catholic University of Milan, Prof. Stanisław Grygiel of the John Paul II Institute in Rome, and Msgr. Piotr Mazurkiewicz of Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw. Cardinal Willem Eijk of Utrecht, Archbishop Marek Jędraszewski of Kraków, and Archbishop-emeritus Luigi Negri of Ferrara-Comacchio made up the impressive ecclesiastical contingent.

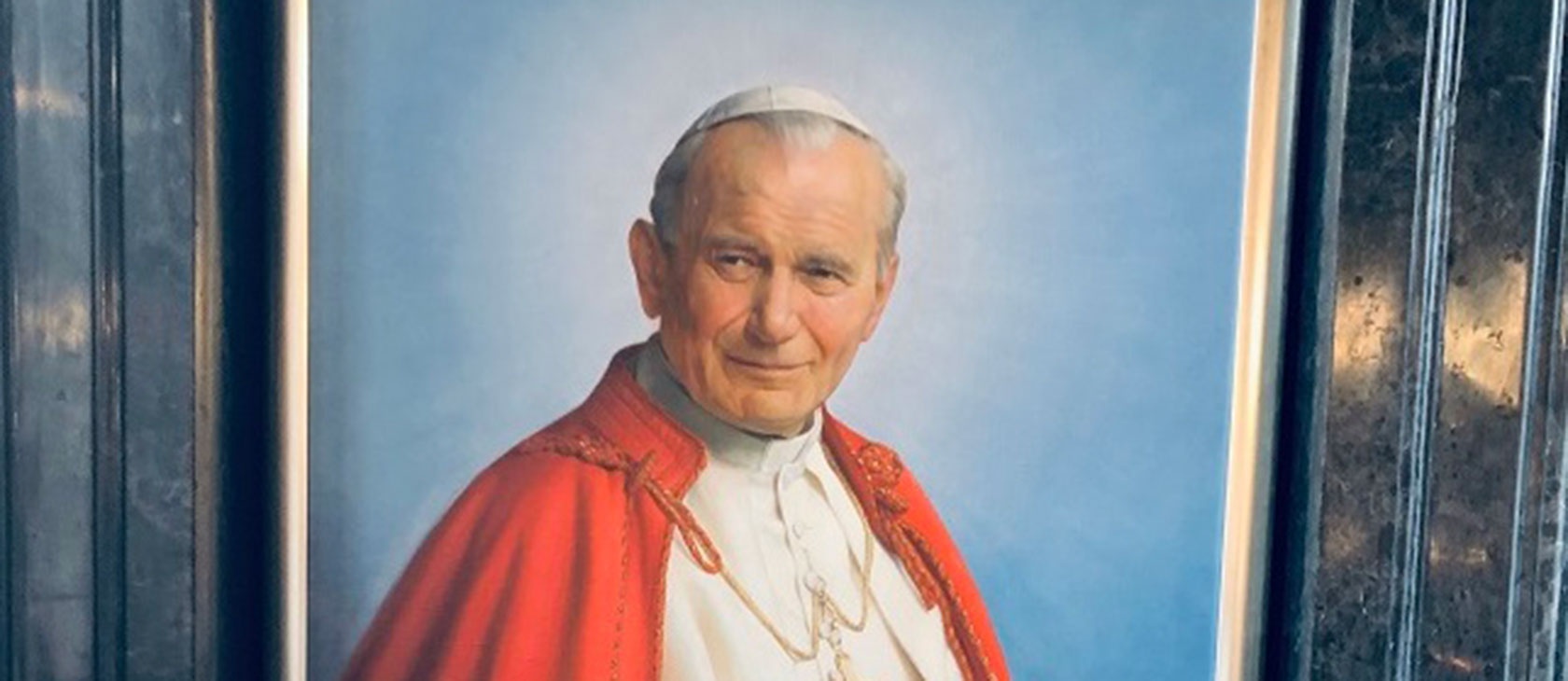

It would be difficult to summarize the discussions other than to say, not surprisingly, that all very much appreciated and loved Pope St. John Paul II. Like last year in the neighboring diocese of Tarnów, I was blessed with the opportunity to speak about my personal and professional experiences with the late pontiff. Then as now, it is clear that his intellectual contribution to the Church is receding from our attention, even in his native land.

Perhaps this is the fate of all but the fewest intellectuals, a humbling reminder to those of us who live and work in the world of ideas. The question of the pope’s governance, especially his handling of clerical sexual abuse, has attracted more attention. JPII’s longtime secretary Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz released a letter thanking Pope Francis for defending the legacy of JPII and his handling of the abuse scandals that continue to plague the Church.

Since it was in the news, I decided to ask the three bishops how they are addressing the scandals. Cardinal Eijk gave the more prepared, organized response, speaking of the need for the Church to take the initiative and create commissions with investigative authority and the involvement of the laity. Archbishop Jędraszewski indicated that, despite all the bad news, the people of Kraków still support their priests. Archbishop Negri said we should never be surprised by the presence of sinners in the Church.

The varied reactions revealed, once again, how different countries deal with the abuse scandals in different ways. To put it bluntly, the Dutch take the most direct approach, the Poles rely on the faith of ordinary people, and the Italians have seen it all before. Context may also explain John Paul’s initially skeptical reactions to abuse allegations. He trained for the priesthood clandestinely during the Nazi occupation of Poland and became a bishop under Communist rule when false accusations meant to discredit the Church were rampant.

None of this is to excuse the shockingly immoral behavior of some priests or the subsequent cover-up by their bishops. But it should not come as a surprise in a two-thousand-year old, universal Church that has always tried to temper justice with mercy. As much as it may satisfy our naturally human desire to see the guilty punished to the fullest degree of the law, it would not be the truly Christian approach in many cases.

With all that’s going on in the US, Italy and Poland, I’ll have more to say about the Church’s involvement with the political world in coming months. For now, I’d like to return to the thought of John Paul II and what it still has to teach us in these chaotic, even depressing times.

Following George Weigel, I’ve long thought that three encyclicals best summarized JPII’s social thought: 1991’s Centesimus Annus, 1993’s Veritatis Splendor, and 1995’s Evangelium Vitae. In the small world of professional Catholic intellectuals, only the first is normally considered a social encyclical, since it commemorates the 100th anniversary of the first modern social encyclical, Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum. Veritatis Splendor is usually claimed by moral theologians of various stripes, while Evangelium Vitae is said to be the pro-life document par excellence. To categorize encyclicals only by their target audience or political/economic content, however, misses what is unique and fundamental to Catholic and by extension JPII’s teaching.

As all the speakers at the Kraków conference noted, John Paul II stressed the centrality of Jesus Christ above all. Russell Hittinger astutely noted that while every pope since the French Revolution wrote about Church-State relations in their inaugural encyclicals, JPII opened his pontificate with Redemptor Hominis, proclaiming the fully divine and fully human Christ as the answer to all our problems. The fact that Jesus did not rule as a temporal king, as many Jews at the time expected the Messiah to do, leaves us perplexed but also free to order our political lives in diverse ways. This is the basis of any kind of Christian liberalism, which is under a fair amount of criticism these days.

Recalling St. John Paul II and his thought should not be merely nostalgic, wishing for the supposedly golden past when the Church and the world were free of problems. It is a strong temptation to fight, I must admit, after spending a week seeing JPII’s image everywhere I went. He himself would urge us to follow Christ, not Karol, just as he would remind that he too is a sinner in need of repentance. In this way, Popes Benedict XVI and Francis have been in perfect continuity with their predecessor, something we proud members of the JPII generation should never forget. We can nevertheless be forgiven for missing the great man.

(Photo credit: Kishore Jayabalan)