Review of Brand Luther: 1517, Printing, and the Making of the Reformation (Penguin Press 2015).

In the lead up to 1617, the 100th anniversary  of the beginning of the Reformation, a flood of celebratory and educational publications poured over Protestant Germany. These publications included sermons, plays, prayers, hymns and, of course, reprints of the works of Martin Luther. That the lead up to the Reformation’s five hundredth anniversary would be accompanied by an analogous flood of new books on the Wittenberg Reformer is entirely consistent with Luther’s own life and legacy—a life and legacy intimately tied to the power of the printed page and the explosive growth of the publishing industry.

of the beginning of the Reformation, a flood of celebratory and educational publications poured over Protestant Germany. These publications included sermons, plays, prayers, hymns and, of course, reprints of the works of Martin Luther. That the lead up to the Reformation’s five hundredth anniversary would be accompanied by an analogous flood of new books on the Wittenberg Reformer is entirely consistent with Luther’s own life and legacy—a life and legacy intimately tied to the power of the printed page and the explosive growth of the publishing industry.

The present deluge of anniversary books on Luther and the Reformation has yet to crest, but in Brand Luther, Andrew Pettegree—a distinguished scholar of both the Reformation and the history of communication—has already given us a refreshingly original account of Luther and his movement that deserves particular attention. Brand Luther includes the usual elements of a traditional biography. All the major events and controversies of Luther’s life are recounted. At every step, however, Pettegree shows how Luther’s rise was in a symbiotic relationship with the printing industry. Thus Pettegree simultaneously tells the history of the explosive development printing in Germany—especially in Wittenberg—and argues that Luther became a brand that reshaped both the book industry and the church.

In 1522, still relatively early in his contest with the church hierarchy, Luther gave this famous account of the reason for his movement’s success: “I simply taught, preached, and wrote God’s Word; otherwise I did nothing. And while I slept, or drank Wittenberg beer with my friends Philip and Amsdorf, the Word so greatly weakened the papacy that no prince or emperor ever inflicted such losses upon it. I did nothing; the Word did everything.” Without evaluating Luther’s claim regarding ultimate, divine causality, we can still say that Luther is correct in the sense of secondary causality. That is, regardless of whether it was ultimately the Word of God or merely the word of Luther, the written and printed word did in fact do everything. Certainly iconography, preaching, liturgy and song had their impact as well, but as Pettegree’s account illustrates, the printed word—the book—was central to the success of the movement.

The sales figures and statistics for Luther’s (and his supporters’) books are sprinkled throughout Pettegree’s account. These numbers are astounding. Pettegree writes, “Within five years of penning the ninety-five theses, [Luther] was Europe’s most published author— ever.” Luther’s Sermon on Indulgence and Grace went through at least two Wittenberg editions, four reprints in Leipzig and two each in Nuremberg, Augsburg and Basel—all in 1518, the first year of its publication. And that was merely the beginning. By the end of 1522, Luther had written about 160 works and these had been published in 828 editions. “The next eight years,” Pettegree notes, “would see the publication of some 1,245 more, an estimated total of some two million copies.” Between 1521 and 1525, during the height of the pamphlet war over Luther’s ideas, “Luther and his supporters outpublished their opponents by a margin of nine to one.”

Truly Luther was a prolific author who sent a constant stream of works to the various Wittenberg publishers. But what explains such a voracious public appetite for these books? According to Pettegree, the Luther brand and its many facets are the key to understanding the unprecedented popularity of Luther’s writings and the wild success of his movement.

One facet of brand Luther is so often stated as to be almost cliché: Luther’s great success was due to his decision to write in the vernacular and thus to relocatea theological contest from the academy to the realm of the common folk. Pettegree, however, carefully nuances this well-worn observation. He points out that Luther’s opponents also wrote in the vernacular and attempted to meet him on the same ground. The difference was that the vernacular books of Luther’s opponents sold miserably, and so publishers—largely irrespective of their own individual religious convictions—chose to print what sold. Thus Luther’s opponents could scarcely find German printers who would publish their books.

“Thus Pettegree simultaneously tells the history of the explosive development of printing in Germany—especially in Wittenberg—and argues that Luther became a brand that reshaped both the book industry and the church.”

The size and format of many of Luther’s works also fueled their success. Luther made great use of pamphlets, or Flugschriften. These short vernacular works were inexpensive to print, used very little paper, could be produced quickly in large quantities and were cheap to buy. As Pettegree points out, many people who had previously never owned a book or who could afford only one or two could now buy dozens of Reformation pamphlets. The Flugschriften were also easily and cheaply reprinted, and so publishers across Germany could print their own editions rapidly to meet local demand. An important contextual factor was also at play here. Due to the political divisions of the Holy Roman Empire, Germany’s publishing industry spanned several sovereign territories and cities. It was thus highly decentralized. This made it virtually impossible for the church hierarchy or the emperor to stem the tide of Luther’s works. The combination of the pamphlet format and the decentralized publishing industry allowed Luther and his supporters to reach vast numbers of people who had never before engaged theological and ecclesial issues.

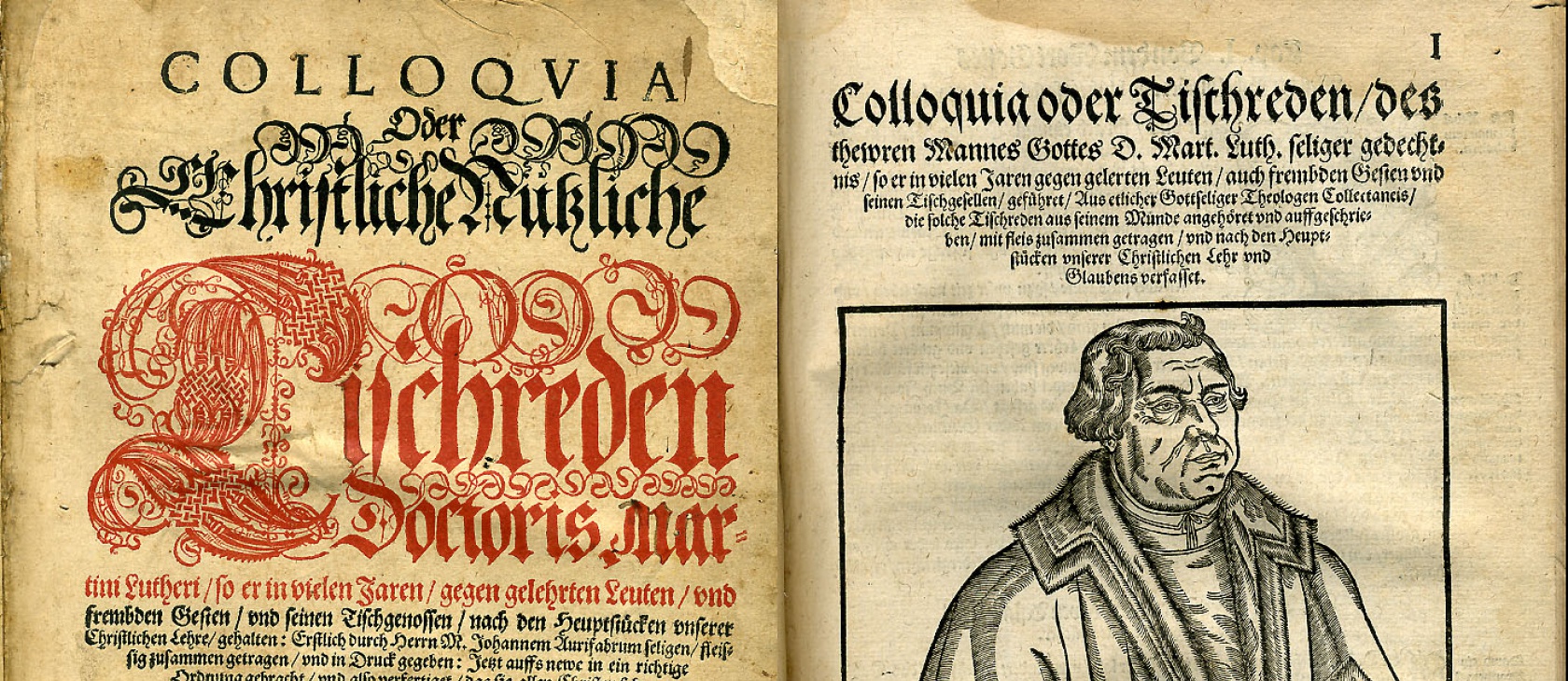

The design of these works was also a critical element in their popularity and branding. One of the most fascinating figures in Pettegree’s account is Lucas Cranach (the elder), who was court painter for Frederick the Wise and whose workshop was in Wittenberg. Cranach was central to the creation of brand Luther not merely for his many famous portraits of the Reformer, but especially for his brilliant iconographical woodcuts that adorned the title pages of Luther’s works. In many ways, Pettegree’s account is as much the story of Cranach’s genius as it is Luther’s. Cranach was central to the crafting of the distinct look of Luther’s works. This gave these publications from back-country Wittenberg a visual appeal that rivaled that of the publications from the traditional printing houses of Europe.

Ultimately Pettegree has carefully elucidated the ingenuity, readability and marketability of Luther’s books and the reciprocal relationship between Luther and the German printing industry. Indeed, in Brand Luther, Pettegree has accomplished a rare feat. He has written something both original and compelling about Luther.

But despite the compelling account of the success of Luther’s books, something still seems to be missing from Pettegree’s answer to that central question: Why these books? That is, why did Luther’s books in particular captivate thousands of people and ignite a movement unlike any in history? Pettegree points to features of the medium and the historical context, such as Luther’s use of the vernacular, the pamphlet format, the decentralization of the German publishing industry, Cranach’s design brilliance and—as Pettegree is apt to note—luck. Absent Luther’s message, however, all these factors fail to explain fully the voracity with which people consumed Luther’s books and brand.

Pettegree undoubtedly knows that Luther’s success was tied to his message of, for example, the doctrine of justification by faith alone and the criticism of the sacramental system. At certain points he mentions how Luther’s early works surgically attacked the church’s doctrine and practice, and he devotes a whole chapter to the way Luther functioned as a pastor for the whole German people. In a short section on Luther’s writings on good works and Christian freedom, Pettegree even recognizes that Luther’s “careful exposition of a healing Gospel . . . struck an increasing chord with the German public.” But on the whole, Pettegree gives little attention to the importance of the message. In fact, he suggests that the radical impact of Luther’s theology “may well have escaped the first generation of readers.” Such a suggestion seems to miss the full picture.

Luther said, “I did nothing; the Word did everything.” Yes, Luther carefully crafted a brand. He did not simply watch the word do the work while he and Melanchthon swigged beer. But it does not suffice to say that Luther’s books alone did the work of reform. Neither does it suffice to say that Luther’s brand alone did the work. A full explanation of the success of Luther’s movement must go beyond the medium to the message. The word did everything.