If you know the name John Dewey, you may associate him with the decline of American education. Many believe that the absence of intellectual rigor and the lack of responsibility in schools can be blamed on Dewey, who has been called the “father of progressive education.” It’s easy for conservatives to dismiss someone described as the “father” of anything progressive, but it may be worthwhile to reconsider John Dewey (1859-1952) in light of new economic challenges posed by automation. According to a study by PricewaterhouseCoopers, advancements in self-driving technology and robotics threaten up to 38 percent of jobs in the United States. How can American schools prepare students to enter a competitive economy ready to upend itself?

How can American schools prepare students to enter a competitive economy ready to upend itself?

Dewey’s reforms addressed similar problems during the Second Industrial Revolution. The unprecedented economic growth at the turn of the 20th century helped to create immense social and political upheaval, which ultimately produced the modern, top-heavy administrative state and the erosion of liberty we see resulting from bigger and bigger government. Chaotic though this time was, Dewey’s challenges pale in comparison to the disruptions that may occur when robots take millions of jobs from American workers. In a global economy, where the United States competes with rising economic powers like India and China, politicians and educators alike call for increased funding for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics curriculum, commonly known as STEM, to help America create new industries and spur new innovations. But, while public schools and federal agencies have pushed STEM-based education to propel students ahead of this trend, it may only prepare students for jobs that will be automated anyway. Even careers in programming and technology may not be safe, not when robots could learn to program better and faster than humans. Is the “father of progressive education” responsible for our dilemma? A closer look at Dewey’s philosophy of education reveals a more complicated picture.

Dewey derived his reforms in part from children’s natural curiosity. Kids want to experience everything for themselves, so classroom instruction should use meaningful activities to teach problem-solving skills, and to test these theories Dewey founded the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago. The name is not misleading, since the school was a laboratory where students (as test subjects) learned math and history through sewing and cooking. Dewey believed students learned best through meaningful, experiential activities, and discouraged memorizing isolated facts because such facts had no real use for anyone, let alone schoolchildren entering the industrialized workforce. New modes of production and new discoveries in science called for new methods in education, so students could solve real problems, not just recite facts. “The mere absorbing of facts and truths is so exclusively individual an affair that it tends very naturally to pass into selfishness. There is no obvious social motive for the acquirement of mere learning, there is no clear social gain in success thereat,” Dewey wrote in The School and Society (1899).

Central to Dewey’s philosophy is his dismissal of “metaphysics.” “Metaphysics” refers to beliefs concerning the existence of God, of unique substances like the “soul” or the “mind,” and other philosophical issues that exist in a realm outside of human experience. Dewey believed that these beliefs, along with moral judgments and religious values, really derived from social customs, and philosophers placed these customs outside of experience -- in metaphysics -- to bind them on everyone else. By Dewey’s day, advances in science had, he believed, refuted such beliefs and offered real, empirical evidence that human beings are basically animals. Ideas commonly accepted in the Western tradition having been proven obsolete, Dewey proposed reforms that reflected both the changing times and the changing conception of what man is. Hence Dewey argued that students learn best through experiential activities since animals, to the extent they learn at all, learn only by experience.

Thus Dewey’s educational philosophy is something of a mixed bag. Yet, we can glean the wisdom in his emphasis on experiential knowledge without accepting the metaphysical premises that provided part of the foundation for that emphasis. If students are to thrive in an automated, post-industrial society, they’ll certainly need an education that cultivates the whole person. STEM-dominated education may prepare students for a career in computer programming, but it may not be long before a robot takes that job, too. Students do not need an education that treats human beings as basically animals, nor do they need a curriculum that looks with suspicion on the preserved wisdom of the Western canon. Instead, students need a liberal arts education that joins the humanities to the sciences and encourages the critical thinking skills and creativity students need to flourish in society and hold a job no robot could take. Only by educating the whole person does a school prepare that individual to take on the whole world.

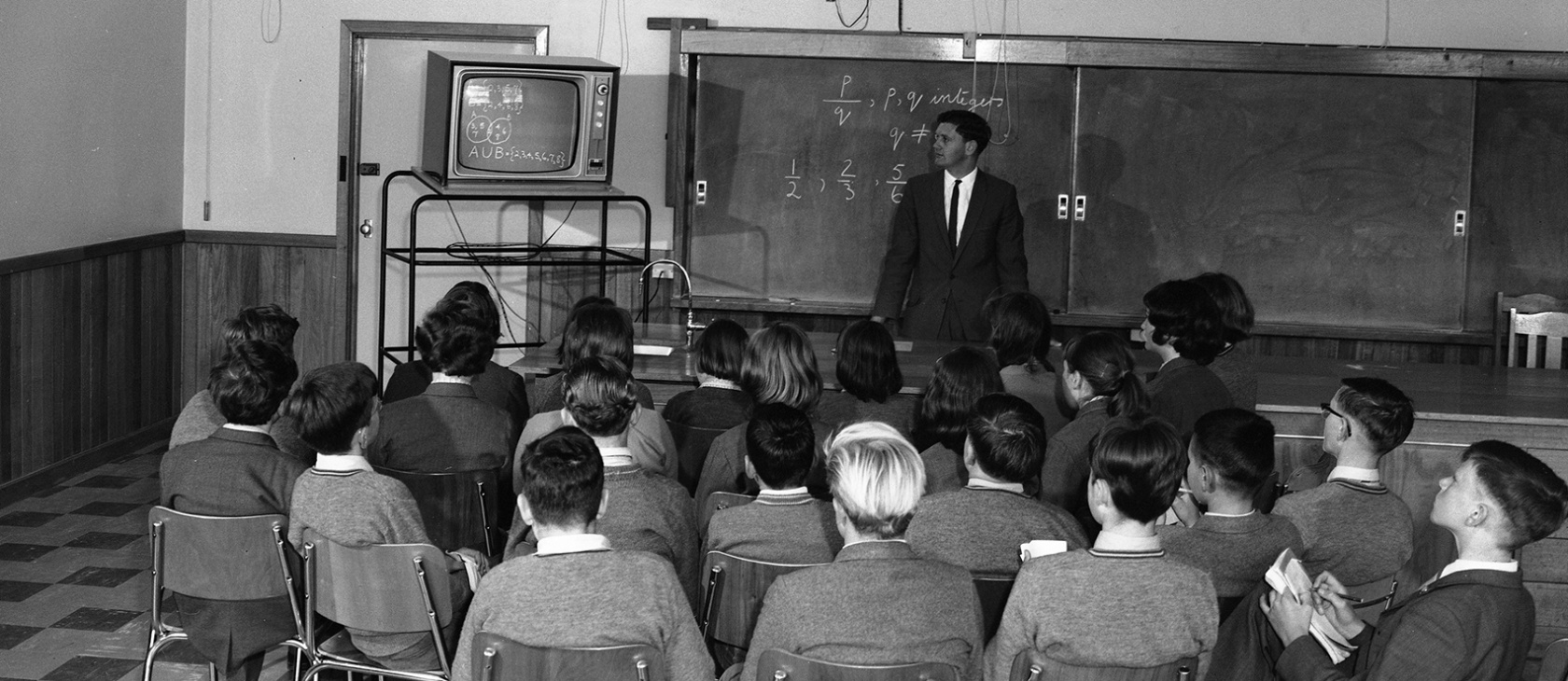

Featured image used under Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC 2.0). Some changes made.