Another sign of the politicization of all aspects of our culture is the latest Criterion Channel tagline for the 1951 film High Noon: “One of the most politically resonant of all Hollywood westerns.” Really? They’re referencing, of course, the screenwriter Carl Foreman’s brief membership in the Communist Party, which eventually landed him on the industry’s blacklist. Fans of the film need not worry, however: This doesn’t mean playing Tex Ritter’s rendition of the film’s theme song “Do Not Forsake Me, Oh, My Darling” backwards yields “The Internationale” communist anthem.

The Gary Cooper oater has received a political makeover by Glenn Frankel in a book that once again covers the story of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) investigations into Tinsel Town communism in the late 1940s and early 1950s. No matter whether readers believe that HUAC and the Hollywood studio blacklists it prompted abrogated constitutionally protected free speech and free association (true – to an extent) or agree that subversive activities were commonplace within the movie industry (also true – to an extent), this book (High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic, Bloomsbury USA) does little to sway opinions either way.

Frankel falls squarely in the first camp, finding fault with HUAC members, studio heads eager to clean the commies out of Hollywood’s closets and anti-communist celebrities such as John Wayne and Ronald Reagan. At the same time he blames the blacklist era for the early demise of actor John Garfield, director Robert Rossen and several others. This is correlation rather than causation and therefore impossible to verify. If so, it wouldn’t be difficult to attribute the early deaths of 1950s matinee idols James Dean and Montgomery Clift to the blacklists had either actor ever been summoned by HUAC or belonged to the Communist Party (they didn’t, but both men indeed died young). No, instead, Dean was a reckless driver and Clift a chronic abuser of alcohol and other drugs. Likewise, Garfield suffered from a chronic heart condition that may or may not have been aggravated by the blacklists and Rossen conducted an extremely dissolute lifestyle that may or may not have been exacerbated by winding up on the blacklist. There’s simply no way to tell for sure.

McCarthyism slurs

While only the crassest student of film history would make light of the careers destroyed or abbreviated by the Hollywood blacklists, the industry conducted a turnaround immediately after such directors and screenwriters as Edward Dmytryk and Dalton Trumbo returned to prominence. Soon the leftward drift of Hollywood accelerated unfettered. Any challenge to the status quo was met with allegations of witch hunts by conservatives and slurs of McCarthyism. And, ever since, Hollywood liberals have depicted themselves as victims endlessly fighting fascistic, narrow-minded and hypocritical philistines. Such movies as The Way We Were (1973); The Front (1976); Marathon Man (1976); Guilty By Suspicion (1991); The Majestic (2001); and Trumbo (2015) all present one-sided depictions of the 1950s Red Scare. At least the Coen brothers tweaked Hollywood communists as useful and inept idiots in Hail, Caesar! (2015). Turner Classic Movies earlier this year even spent a month spotlighting movies made by blacklisted writers, actors and directors as well as several overheated documentaries and side commentaries by host Ben Mankiewicz – both presuming the complete innocence and benign intent of everyone brought before HUAC.

Soon the leftward drift of Hollywood accelerated unfettered.

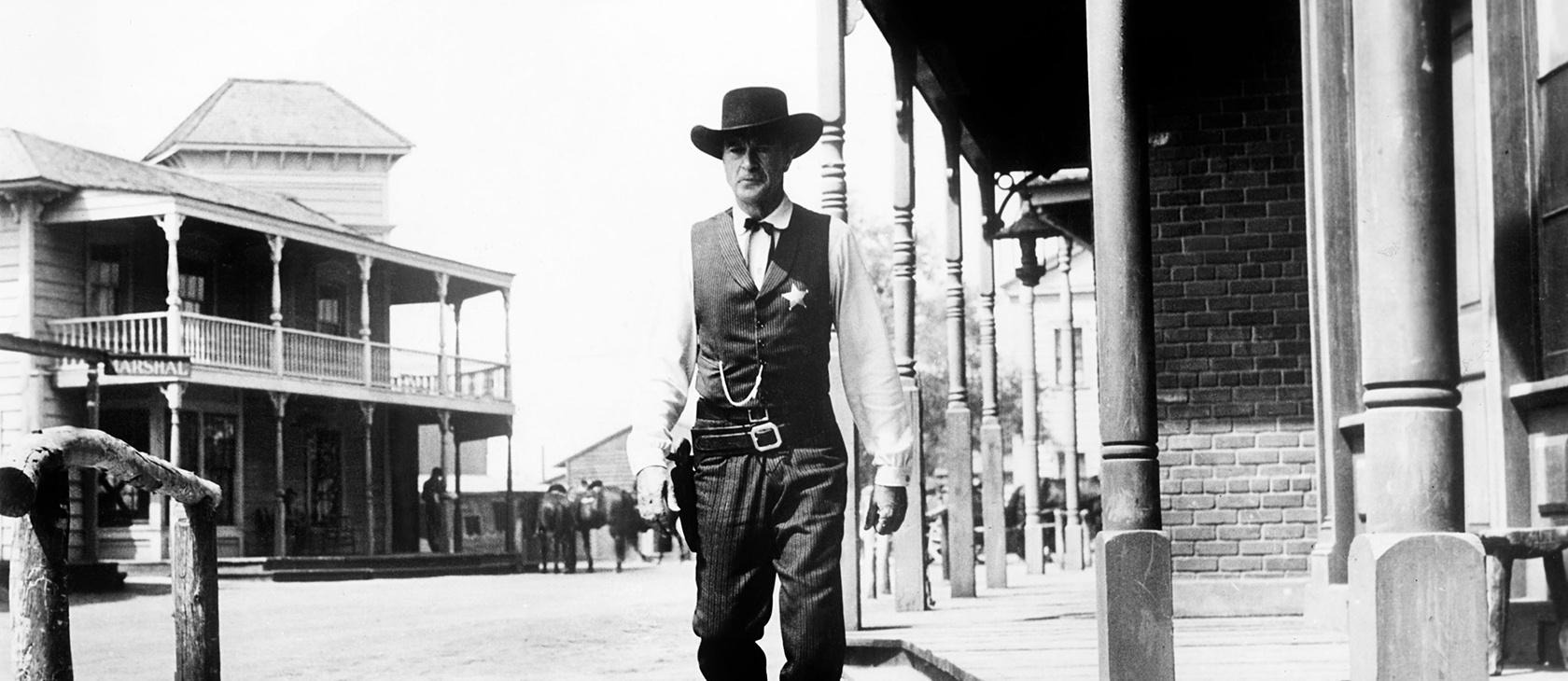

There are shelves full of books dealing with the topic, Frankel’s being among the most recent. It’s long been speculated that High Noon screenwriter Carl Foreman – who received an Academy Award for his efforts – based his story on his own fears of HUAC, which eventually became realized once production of the film began. That explanation holds for those willing to see in Gary Cooper’s Oscar-winning portrayal of Marshal Will Kane a depiction of a man unfairly forced to go it alone against the forces of evil after cowardice infects his fellow townsmen. At least that’s what Foreman seemingly told anyone who would listen in the decades after the film was recognized as a cinematic classic and Foreman was forced to move to London temporarily in order to find work. High Noon supporting actor Lloyd Bridges also found his past membership in the CPUSA a major roadblock in his career.

Trouble is, the allegorical premise Foreman allegedly intended for his screenplay doesn’t necessarily square with its intended target; therefore rendering Frankel’s central thesis more or less a vague and bitter hypothesis perpetrated by Foreman and perpetuated by Frankel for publicity and sales. Other films having nothing to do with HUAC attained classic status by reworking the same premise as High Noon, including those identified by Frankel and familiar to any self-professed film geek. For example, Spencer Tracy in John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock (1955) and Tom Scofield as Sir Thomas More in Fred Zinnemann’s adaptation of Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons (1966) both cover the same territory of one man left alone to fend for himself. Coincidentally, Zinnemann won Oscars for directing both High Noon and A Man for All Seasons. It should be added that, as Cooper’s battle with Frank Miller’s gang relied on the help of Grace Kelly, Henry Fonda had Henry Morgan to assist his fight against mob justice in The Ox-Bow Incident (1943). Further, the script won an Academy Award for Best-Adaptation from another source, which, in this case, was the 1947 short story “The Tin Star” by John M. Cunningham. There truly is nothing thematically new under the Noon sun, to misquote Ecclesiastes.

Hadleyville hypocrites

However, notes Frankel, the film did have its detractors. Right-wing actor John Wayne, for one, was outspokenly dismayed about the scene in which Will Kane attempts to recruit a posse during services in the Hadleyville church. Marshal Kane is at first upbraided by Minister Mahin (Morgan Farley) for possessing the audacity to show up in a church seeking assistance on the same day Kane was married elsewhere in a civil ceremony. Afterwards, Dr. Mahin apologizes and gives the floor to Kane, who quickly enlists a group of able volunteers. Their support fades, however, during a speech by Mayor Jonas Henderson (Mitchell), in which he pronounces bloodshed in the streets of Hadleyville will negatively impact outside investment in the town. This prompts Mahin to conclude in a manner familiar to students of socialist realism: “The commandments say ‘Thou shalt not kill,’ but we hire men to go out and do it for us. The right and the wrong seem pretty clear here. But if you’re asking me to tell my people to go out and kill and maybe get themselves killed, I’m sorry. I don't know what to say. I'm sorry.” In other words, religion does nothing to inspire true heroism but only hypocrisy, and monetary concerns are paramount.

Compare the mayor’s speech with what Howland Chamberlain’s hotel clerk tells Amy Fowler Kane (Grace Kelly). The clerk’s sneering disdain for Kane is explained by law and order being bad for a hotel business presumably reliant on illicit activities. Here, the capitalist smear is not hypocrisy but greed. Coincidentally (or not), Chamberlain’s hostile testimony before HUAC resulted in High Noon being his last cinematic performance for 25 years. Such was Wayne’s rancor; he and director Howard Hawks allegedly created Rio Bravo (1959) as a rebuttal with not only one but two crooners on the soundtrack as well as performing in the film itself: Rick Nelson and Dean Martin. Take that, Tex Ritter!

The Mythic Western

The Duke may have been correct that High Noon grants short shrift to the American ways of faith and prosperity. The mythopoeticized American West is a blank canvas on which contemporary artists may project their social views for the public to both interpret and react accordingly or simply ignore. My preference is to view the town of Hadleyville in much the same way as, say, David Milch’s eponymous town in Deadwood. In that series, the Wild West was a laboratory for spontaneous order in which the rule of law and ethical behavior organically evolve following an initial burst of unregulated financial activity.

Fortunately, however, Frankel’s analysis of High Noon is actually two books in one. The far more interesting and enlightening story is a How It’s Made tale of a much-beloved Best Picture Academy Award winner. Frankel excels at recreating the artistic rumpus that resulted in the collaborative effort between Foreman, Cooper, Zinnemann, studio boss Stanley Kramer, composer and songwriter Dimitri Tiomkin (also an Oscar winner for his efforts) and a remarkable supporting cast of Hollywood veterans (Lon Chaney, Jr., Thomas Mitchell and Morgan) and newbies (Bridges, Kelly, Katy Jurado and Lee Van Cleef). Readers may come to Frankel for the communist controversy, but they’ll be far more engaged by the creative analysis of one of Hollywood’s most beloved films.

So, forgive me if I go it alone against Frankel, Foreman, Criterion and Ben Mankiewicz by refusing to buy into the whole revisionist High Noon anti-HUAC and “politically resonant” megillah. I’d rather help Grace Kelly onto the buckboard, grab the reins of the wagon, and ride out of Hadleyville with the knowledge Hollywood can make great movies without exaggerating the politics of their histories.