How can human society form and raise up virtuous people?

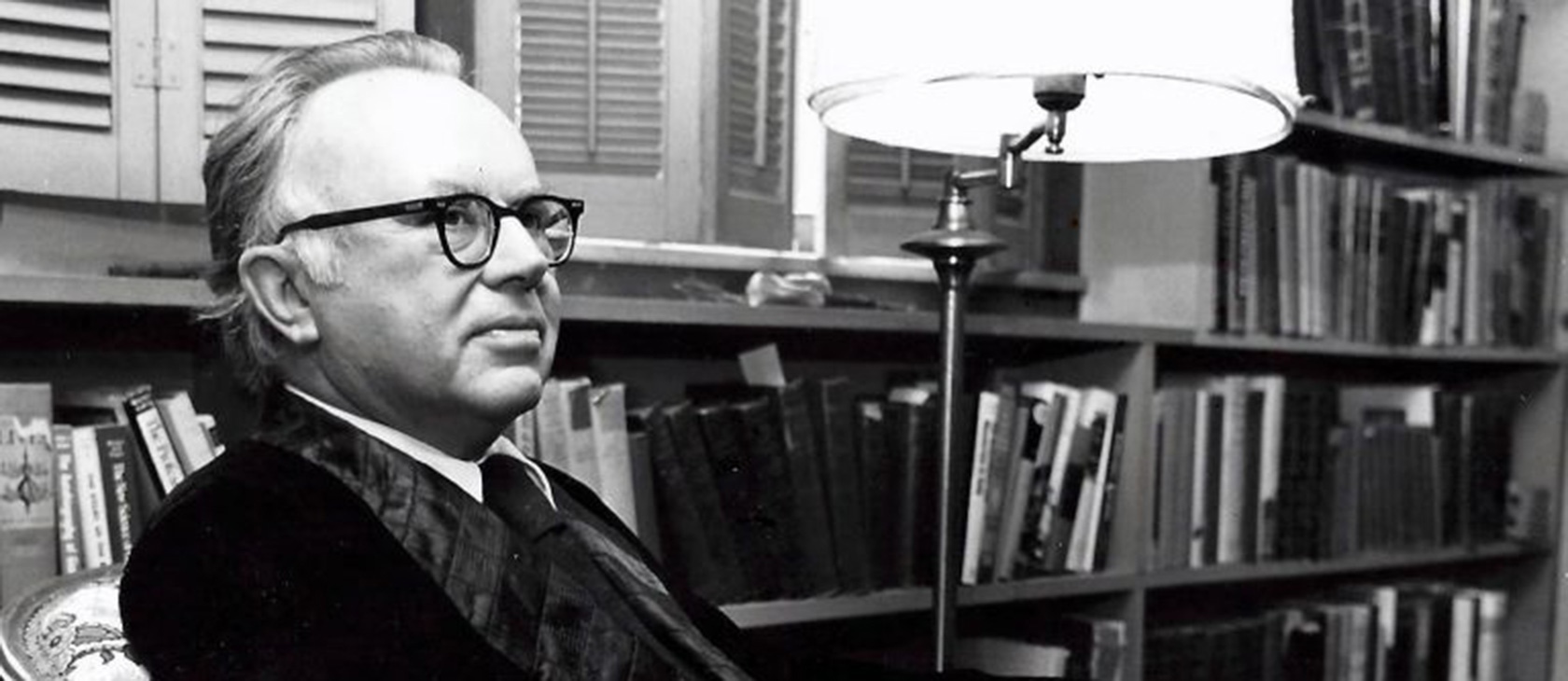

In the Summer/Fall 1982 issue of Modern Age, Russell Kirk explored this perennial question in an essay titled, “Virtue: Can It Be Taught?”

Kirk defined virtues as “the qualities of full humanity: strength, courage, capacity, worth, manliness, moral excellence,” particularly qualities of “moral goodness: the practice of moral duties and the conformity of life to the moral law; uprightness; rectitude.” Despite modern attempts to supplant vigorous, active “virtue” with passive “integrity,” people “possessed of an energetic virtue” are still needed, particularly in more turbulent times.

Can such a thing be taught? Can virtuous citizens be formed by tutoring and other rational forms of education?

Moral vs. Intellectual Virtue

Kirk cited this as the pivotal argument between Socrates and Aristophanes. The former believed that “virtue and wisdom at bottom are one.” “Development of private rationality” could impart virtue to the next generation. The latter, along with Kirk, was quite skeptical of this. “For we all have known human beings of much intelligence and cleverness whose light is as darkness.”

“Greatness of soul and good character are not formed by hired tutors, Aristophanes maintained: virtue is ‘natural,’ not an artificial development,” Kirk explained.

Whether Aristophanes thought that virtue was an inborn, nigh-biological inheritance or a result of nurture was left unanswered. In any case, Kirk traces a compromise with Aristotle, who upheld two kinds of virtue—moral and intellectual:

Moral virtue grows out of habit (ethos); it is not natural, but neither is moral virtue opposed to nature. Intellectual virtue, on the other hand, may be developed and improved through systematic instruction—which requires time. ln other words, moral virtue appears to be the product of habits formed early in family, class, neighborhood; while intellectual virtue may be taught through instruction in philosophy, literature, history, and related disciplines.

Although Kirk understood both of these virtues and saw each as a worthwhile human pursuit, he elevated moral virtue as a universal need for a healthy civilization. He, alongside the great Romans and his own intellectual lodestar Edmund Burke, thought that “the sprig of virtue is nurtured in the soil of sound prejudice; healthful and valorous habits are formed; and, in the phrase of Burke, ‘a man’s habit becomes his virtue.’ A resolute and daring character, dutiful and just, may be formed accordingly.”

Kirk was adamant that intellectual virtue must not be divorced from moral virtue and saw moral virtue as the most important good to secure. Citing the example of Solzhenitsyn, Kirk believed that the former should be wielded to defend and uphold the latter.

The Threat of Modernity

However, Kirk was quite concerned about whether the culture of 1980s America could provide such nurture. He believed that moral virtue required mentoring via “example and precept,” and this was most often conveyed by the family. To see virtue, and then to have it made explicit in pious instruction in duty, is essential in bringing whatever innate (or supernaturally granted) virtue to flower. Unfortunately, modern life threatened the very soil necessary for virtue.

“In no previous age have family influence, sound early prejudice, and good early habits been so broken in upon by outside force as in our own time,” he worried, “Moral virtue among the rising generation is mocked by the inanity of television, by pornographic films, by the twentieth-century cult of the ‘peer group.’”

Unfortunately, modern life threatened the very soil necessary for virtue.

Meanwhile, affluence and increased mobility had further removed the rising generation from their parents and grandparents. Ease of travel has severely weakened the extended family, with thousands of miles separating the generations from each other.

Moreover, the busyness and distractions of modern life have mightily increased, even since Kirk’s day. Not only do both parents (if there are two parents in a household) work full or part-time jobs, but the workplace further intrudes upon the home. Meanwhile, children are sequestered to their own age group in enormous educational facilities and highly orchestrated extracurricular activities. Sadly, many families spend their “down time” in front of various screens, passively consuming digital entertainment rather than interacting with one another (an issue that Andy Crouch has responded to in one of his latest books). Religious participation is also on the decline, again removing an opportunity for children to witness their parents and other adults in “unguarded” social moments when virtue is mostly clearly exemplified.

Toward a Restoration of the Family

Refreshingly, Kirk does not lay the responsibility for addressing this crisis on the shoulders of the church or schools (public or otherwise)—at least not necessarily. Although he sees both in need of improvement and reform, he knows that they cannot replace the family and civil society (the latter of which can be found in churches and schools, but is certainly not limited to them). It is the family that must be recovered and restored to health.

And so it falls on parents in particular to consider how we might better impart virtue to our children. Are we spending enough time with them, where they see our actions, perceive our principles and values, and understand the duties that they will be responsible for? American parents can spend much time, energy, and wealth to secure a bright academic and professional future for their offspring. Do they give the same to impart moral virtue to those given them? Are they complicit in creating an artificial generation gap, effectively leaving their own children spiritual and cultural orphans? And what can shock them from concerns over wealth and status to the preservation and stewardship of the good, to ignore the pressures to pursue an unhealthy domestic life?

Kirk had a similar concern. At the end of his essay, he offered a prognostication: that Americans would need to endure difficulty to be awakened to the need for vigorous virtue. In other words, hard times can make good men, making evident the desirability and necessity of certain qualities that people—individually and communally—must have to flourish.

In preparation for such trying seasons, it is up to us to pursue such virtues ourselves and to instill them in our own children, even as we inhabit a moment of apparent ease.

This is the first in a series celebrating the work of Russell Kirk in honor of his 100th birthday this October. Read more from the series here.

Featured image courtesy of The Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal.