Cultural critics, in politics and academia, insist that the United States must atone for its shameful history of discrimination against minorities. Thankfully, the Supreme Court’s Espinoza case gives our justices the opportunity to do just that: to strike down antiquated, counterproductive, and discriminatory laws disfavoring religious schools and paving the way for greater school choice.

Perhaps the only prejudice in U.S. history not highlighted by the Woke is America’s pervasive anti-Catholicism. John Winthrop wrote in 1631 that the first reason the Pilgrims wished to establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony was “to raise a Bulwark against the kingdom of AntiChrist which the Jesuits labour to rear up in those parts.” Anti-Catholic bigots worried aloud that Catholicism was incompatible with the American experiment (a position they strangely share with today’s Catholic Integralists). As a result, North Carolina did not allow Roman Catholics to hold public office until 1835.

Perhaps the only prejudice in U.S. history not highlighted by the Woke is America’s pervasive anti-Catholicism.

The same year, abolitionist Lyman Beecher encapsulated this view when he wrote that Catholicism is a “despotic religion” that “never prospered but in alliance with despotic governments … and at this moment is the main stay of the battle against republican institutions.” (Emphasis in original.) The hub of the purported conspiracy, he wrote, lay in Catholic parochial schools. “Catholic powers are determined to take advantage” of American children “by thrusting in professional instructors and underbidding us in the cheapness of education – calculating that for a morsel of meat we shall sell our birth-right,” he wrote.

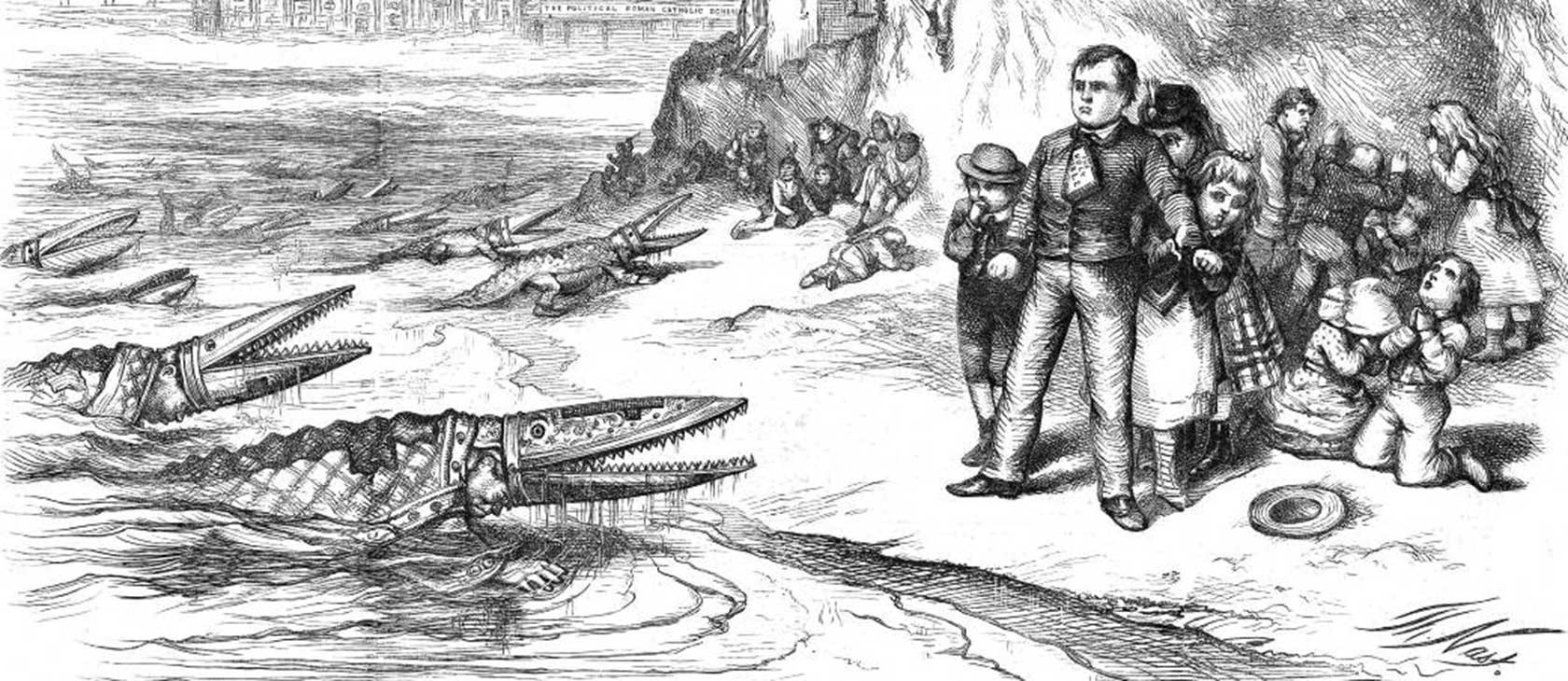

His views took pictorial form when cartoonist Thomas Nast produced the most virulently anti-Catholic cartoon in American history for Harper’s Weekly on September 30, 1871. Nast depicted Catholic bishops as alligators, rising from “The American River Ganges” to devour innocent American children, as the “U.S. Public School” stood as the ramparts against the Vatican’s onslaught. The magazine reprinted the cartoon, by popular demand, in May 1875.

The high-water mark of bigotry against Catholic schools came that winter with the Blaine amendment, introduced by James G. Blaine, the onetime Speaker of the House, President James Garfield’s secretary of state, and failed 1884 Republican presidential candidate. Blaine tried to amend the U.S. Constitution so that “no money raised by taxation in any State, for the support of public schools, or derived from any public fund therefor, nor any public lands devoted thereto, shall ever be under the control of any religious sect.” Blaine fell four votes shy of Senate ratification, but 37 states added similar amendments to their state constitutions.

The amendment targeted the burgeoning number of Roman Catholic schools, as U.S. public schools already taught Protestant Bible lessons, prayers, and hymns. But soon, government-sponsored discrimination would boomerang. The Supreme Court struck down state-led prayer in public schools (Engel v. Vitale, 1962), state-led Bible reading (Abington School District v. Schempp, 1963), direct state funding of religious schools (Lemon v. Kurtzman, 1971), posting the Ten Commandments in public schools (Stone v. Graham, 1980) and state-sponsored prayer at public school graduations (Lee v. Weisman, 1992). The public schools – established to teach “religion, morality, and knowledge” – had become the freeway to the Secular City. And the Blaine amendment in 37 states now denied Protestant schools state funding. This should serve as a lesson for those of any faith who embrace “The Caesar Strategy” of using the power of the state for their own religious ends; the power they establish will be used against them once the state is controlled by their opponents.

[s]tudents and teachers do not 'shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate'

However, “[s]tudents and teachers do not ‘shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,’” as the Trump administration recently noted in a federal guidance to school districts. This comes against the backdrop of the U.S. Supreme Court, which heard oral arguments last week in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, which could strike down all 37 Blaine amendments.

In 2015, the Montana legislature gave a dollar-for-dollar tax deduction of up to $150 to anyone who donated to a private, nonprofit scholarship fund for needy schoolchildren. The independently administered scholarship let parents send their children to any private school, religious or secular. But state officials told Kendra Espinoza not to apply, because she sends her two children to a Christian school in Kalispell.

With the help of the Institute for Justice, she and two other parents sued, arguing the state infringed their religious rights under the First Amendment. In December 2018, the Montana Supreme Court ruled that, through the program, state revenues “indirectly pay tuition at private, religiously-affiliated schools.” To assure no such entanglement of funds, justices struck down the entire program.

There is reason to believe the Supreme Court will overturn their ruling, and more reason people of faith should hope it does. One of these is plain logic: A tax deduction is not a subsidy. By offering a tax deduction, the state does not give anything to the school or the taxpayer; it merely refrains from taking some portion of the taxpayer’s earnings. The IRS allows tax deductions for charitable gifts, the largest share of which go to religious institutions. This does not constitute government “funding,” unless you believe all citizens’ money properly belongs to the government.

Supreme Court precedent is on Espinoza’s side. In the 1983 Mueller v. Allen ruling, justices upheld a state tax deduction for the cost of tuition, books, and transportation to any school, public or private. The write-off constitutes an “attenuated financial benefit, ultimately controlled by the private choices of individual parents, that eventually flows to parochial schools from the neutrally available tax benefit.”

Indeed, in 1947, justices ruled that the state could directly reimburse parents for the cost of transporting students to parochial schools (Everson v. Board of Education of the Township of Ewing). And in 2002, the Supreme Court upheld Cleveland’s school choice program in Zelman v. Simnmons-Harris, even though 96 percent of students chose religious schools. Justices found the city “provides assistance directly to a broad class of citizens who, in turn, direct government aid to religious schools wholly as a result of their own genuine and independent private choice.”

The danger is that government funding will bring government regulation, such as insisting on a curriculum that violates the religion of the recipients. A tax deduction solves this problem, while respecting parental rights.

The danger is that government funding will bring government regulation, such as insisting on a curriculum that violates the religion of the recipients.

The rights of parents to educate their children in their faith should be primary to all people of faith. “The prime truth in the whole schools issue,” Abraham Kuyper wrote, is that parents are the only people “called by nature … to determine the choice of school” for their children. “Parental rights must be seen as a sovereign right in this sense, that it is not delegated by any other authority, that it is inherent in fatherhood and motherhood, and that it is given directly from God to the father and mother.”

Similarly, the Roman Catholic faith defines parental rights as primary and pre-political. “Parents have the first responsibility for the education of their children,” according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

Curiously, those who decry paternalism when the government bans people from using food stamps for junk food have nothing to say about the state constricting the authority of parents to educate their own children. Often, they demand it.

Those who believe education provides the key to lift bright young students out of poverty should champion children’s access to the best quality education, public or private. And those concerned with making reparations for America’s “tragic history” should support overturning these relics of anti-Catholic discrimination.