Society praises equality as an absolute good. Certainly, equality before God and the law are pillars of a free society. However, measuring economic equality is often misleading for three key reasons.

I was reminded of this by a new Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) report on income inequality in Great Britain released on Wednesday. The BBC’s headline “UK inequality reduced since 2008” typifies the media coverage.

However, the study reveals that much of the leveling came about because the wealthiest British citizens are worse off after the Great Recession.

“Incomes at the 90th percentile have fallen by over 10%,” the report says. While low incomes have risen by about the same amount, losing 10 percent of the wealth in the top income bracket far exceeds gaining a tenth at the bottom. The UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) specifies that “income for the richest fifth of households has fallen by £1,900 (or 3.4%) in real terms” since the Great Recession.

The fact that wealth destruction reduces inequality is one indication that “equality” is the wrong measure of economic well-being. The loss of the well-to-do does not improve the lot of the struggling – or those “just about managing,” in the UK’s government’s favored parlance. It merely depletes the pot of wealth available for use within a society.

Inequality is misleading for a second reason: It does not reflect people’s economic conditions or trajectory. The IFS report gets closer to a helpful metric when it notes, “Absolute poverty (according to the government’s official measure) has changed little.” However, this is less helpful than it would seem. The UK government defines poverty as “equivalised disposable income that falls below 60% of the national median in the current year.” That is, the UK’s definition of poverty does not measure privation; it measures inequality.

Surely, someone making 60 percent of the current UK median income would not be considered prosperous by transatlantic standards. However, linking “poverty” to a floating measure like median income muddies the waters because, as a nation becomes richer, so do “the poor.” Imagine a country in which the national median income is $1 million. Someone making $590,000 a year may fall below 60 percent of the median, but that person would hardly be impoverished. Similarly, those making more than $168, the actual median per-capita income of Burkina Faso, are no better off for their neighbors’ poverty.

The British have long understood this. Margaret Thatcher once responded to an accusation that inequality had grown under her tenure by saying, “What the honorable member is saying is that he would rather that the poor were poorer, provided that the rich were less rich. … So long as the gap is smaller, they would rather have the poor poorer. You do not create wealth and opportunity that way. You do not create a property-owning democracy that way.”

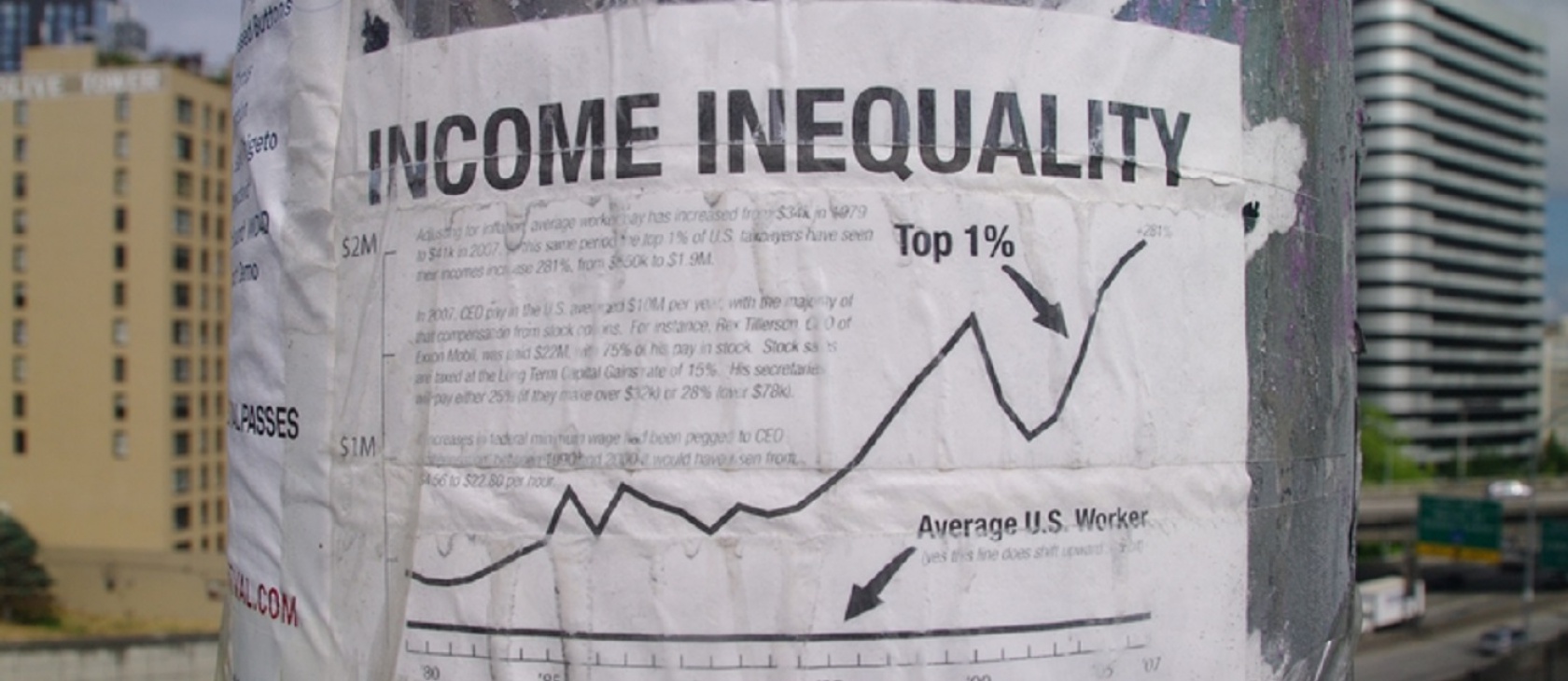

This hints at the third reason that economic “equality” is misleading: It assumes the wealthy become wealthier at the expense of the poor. Experience tells us that the fortunes of every citizen are tied together. A poor person loses ground if a wealthy person lacks the funds to pay his salary, chooses not to invest in his start-up, or does not buy the goods offered by his employer. And the poor person has less ground to lose. The latest ONS statistics reveal empirically how rich and poor have risen together over the long term:

The median disposable income for the richest fifth of households in 2015/16 was 2.3 times higher than in 1977 (when comparable records began). The median income of the poorest fifth of households has also grown over this time, but the rate of growth has been slower (2.0 times higher in 2015/16 than 1977).

For this reason, the Catechism of the Catholic Church upholds the need for “solidarity … between rich and poor … between employers and employees in a business,” and its social teaching condemns “the class struggle.”

Finally, the most important reason that focusing on economic inequality is misleading – which I buried in this article – has nothing to do with economic charts or data sets. Variable annual incomes reflect the differing gifts, characteristics, personalities, circumstances, exertions, and productivity levels of each unique individual as he or she was created by Almighty God. No two individuals are alike; therefore, their life’s work, and the remuneration it is able to fetch on the free market, differ. The wonderful diversity with which the Lord graced the human race is no mistake. It in some sense reflects His own many-faceted glory and allows for some to exercise their spiritual gift by providing for the needs of others. For the human race to thrive, once must appreciate human anthropology as lovingly fashioned by its Creator.

(Photo credit: mSeattle. This photo has been cropped and modified for size. CC BY 2.0.)