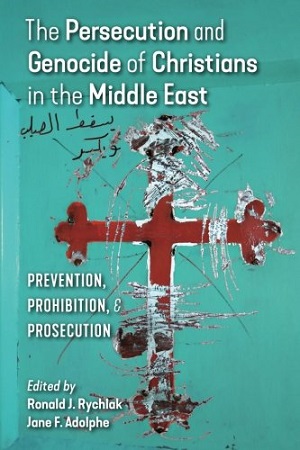

The Persecution and Genocide of Christians in the Middle East: Prevention, Prohibition, and Prosecution. Ronald J. Rychlak and Jane F. Adolphe, editors.

Anglico Press, 2017. 406 pages.

A book about religious persecution is perhaps an unusual place to find a call for Western rejuvenation. Yet readers of The Persecution and Genocide of Christians in the Middle East: Prevention, Prohibition, and Prosecution, edited by Ronald J. Rychlak and Jane F. Adolphe, will discover within its many detailed and expert chapters a special call for the West to live up to its own heritage.

A book about religious persecution is perhaps an unusual place to find a call for Western rejuvenation. Yet readers of The Persecution and Genocide of Christians in the Middle East: Prevention, Prohibition, and Prosecution, edited by Ronald J. Rychlak and Jane F. Adolphe, will discover within its many detailed and expert chapters a special call for the West to live up to its own heritage.

While the collection of essays addresses the persecution of Christians throughout the world, this review will focus on its Middle Eastern observations, while commending readers to avail themselves of its many other insights into the oppression and persecution of Christians elsewhere.

Christian persecution: Ancient hatred, modern export

In her introductory essay, Nina Shea makes clear that the brutal persecution of Christians in the Middle East began long before the rise of ISIS. Her expert findings are enhanced by the fact that she took pains to seek and report the perspective of local Christian clergy and laity who know the persecution firsthand. Their stories are heartrending, and their plight beyond adequate description.

What Christians face is not just one evil faction embodied by ISIS, but a pervasive Islamist sentiment among local Muslims exploding at times in such varied forms as the assassination of clergy, the desecration of churches, and the enslavement of women, all of which are perpetrated specifically for “religious” reasons. Most of the jihadist rebel groups who claim responsibility for these atrocities have only recently morphed into ISIS. Yet Shea makes clear that their destructive mission predates the proclamation of the new caliphate.

Shea’s chapter, especially, deserves commendation for its eyewitness accounts of persecution, which are bafflingly absent from the international mass media coverage of the “rebel” groups and “uprisings.” The fact that these realities are not widely reported or robustly addressed by Western governments is indicative of a double standard that severely hampers the battle against Salafi-jihadi extremism.

Just as Shea’s quotations of Christian victims and surviving leaders is invaluable, so are Geoffrey Strickland’s reliance on direct citations of ISIS’s public pronouncements. Their total ideological commitment to a genocidal cause is, as Strickland writes, “haunting.” In their worldview, every brutality they inflict is not only justified, but proudly proclaimed. ISIS often goes so far as to favorably compare its criminal acts to the immorality of “infidels.” Rape? They compare it to Western pop culture and prostitution (p. 196).

Almost as disturbing are Strickland’s examples of mainstream Islamic failures to sufficiently repudiate some of ISIS’s central tenets. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, while it has officially denounced ISIS, continues its ban on the building of churches within its borders. The country’s Grand Mufti recently called for the destruction of more Christian churches. Strickland writes:

In addition, there are reports "of state-approved primary and secondary school textbooks" that teach "that Christians are enemies of the Muslims and that there is perpetual clash with them; that the Crusades have not ended and the 'Crusader Threat' continues; that the life of a Christian is worth a fraction of that of a free Muslim male; that Christians are swine; and that Muslims are to hate Christians."

Disseminating this information is left to Western Christian organizations such as the Knights of Columbus, and many others, which make a point of applying Christian principles to the plight of the persecuted, and sharing eyewitness accounts with the American public and Western governments. It is perhaps in part thanks to their robustly religious worldview that they are able to clearly identify the specifically “religious” ideology of Islamism, which Robert A. Destro carefully defines as a Salafist-jihadi ideology in his own chapter.

Freedom of conscience and the inviolable dignity of the individual stand at the heart of 2,000 years of Western intellectual, moral, and philosophical development.

Destro, in a perceptively analytical essay, concurs with Shea that ISIS is not a well-contained, singular threat, but rather one front in a global movement. He recommends a comprehensive analysis of what he terms the “malevolent threat matrix” — the global, ideologically coherent system of support that connects the dots linking criminal terrorism across the Atlantic and the Mediterranean – from Mosul, to Paris, to Miami.

Using his malevolent threat matrix, the U.S. would be able to identify a wide support network for Salafi-Jihadi terrorism that includes material supporters — including donors, bankers, and nations like Turkey and Saudi Arabia — and logistical supporters such as the recruiters. Those who radicalize Muslims into violent fundamentalism often do so under the guise of prison chaplaincies, madrassas (Muslim schools), and mosques, not only in the Middle East, but in Western Europe and the United States.

Textbooks such as those disseminated in Saudi Arabia, Strickland writes, "are distributed throughout the Saudi public school system, including to academies it runs in many capitals of nations throughout the world, and to other Islamic schools globally." An ideological storm is brewing.

Applying Western legal and moral thought to the threat of Islamism

As Kevin H. Govern points out in his essay, transatlantic nations and their allies (and potential allies) in the Middle East are extremely well-equipped for an ideological confrontation with global Islamist jihad. Most of the remaining essays of this book accentuate traditions of thought, from the Catholic Church’s history of teachings on religious tolerance, to the twentieth century United Nations and its many pronouncements on the dignity and protection of vulnerable minorities. From the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man, to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, to the many declarations bolstering the rights of minorities, women, and children, the modern world abounds with the legal and moral wherewithal needed in the fight against ISIS. The humanity of the West, and the indefensible barbarism of Salafism, could not be more clearly contrasted.

“Imagine if the Pope today called for the destruction of all the mosques in Europe,” Strickland writes. “Even more absurdly, imagine if the Vatican today issued official educational materials teaching that the life of a Muslim is worth a fraction of that of a free Christian male, Muslims are swine, and Christians are to hate Muslims?"

It is heartening that the suggestion of a pope denigrating Muslims is, as Strickland puts it, “absurd” to Western Christians. Yet it only sounds absurd against the backdrop of a highly sophisticated civilization with Judeo-Christian respect for human dignity at its heart.

There are encouraging signs that Western liberty, when defended, can move mainstream Islam to distance itself from jihadism and respect human rights. In 2000, members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation "officially resolved to support the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam, wherein persons have [the] ‘freedom and right to a dignified life in accordance with the Islamic Shari'ah,’ without any discrimination on grounds of ‘race, colour, language, sex, religious belief, political affiliation, social status or other considerations,’" Govern writes.

The West must be the West again

The book’s last essay (and its most accessible to the layman), written by Ave Maria Radio’s Al Kresta, presents a cogent analysis and call-to-arms for readers.

First, Western media, legislators, and officials exhibit an appalling lack of urgency in response to the persecution of Christians, especially in the Middle East. Kresta recounts activist Michael Horowitz’s story of a Clinton State Department official spurning his pleas on behalf of oppressed Christians. “Don’t you understand how divisive this is?” the dignitary asked. Human rights advocate Nina Shea had no better luck when she approached George W. Bush’s Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, who dismissed her pleas by saying, “We can’t be sectarian.”

Second, Western Christians are also mostly silent, due to a prevailing ignorance of the persecution of their suffering brethren, and to a lack of unity between Christian denominations. If Western Christians were both aware of and united against anti-Christian bigotry and terrorism, Kresta argues, they could present a united front and move national powers toward effective action. Catholic and other Christian researchers ultimately presented the U.S. government with an ultimatum which compelled President Obama’s Secretary of State, John Kerry, to officially designate ISIS’s warfare against Christians, Yazidis, and other Middle Eastern religious minorities as a “genocide.”

Kresta drives home his central argument by quoting Dr. Timothy Shah’s presentation at the 2015 conference titled “Under Ceasar’s Sword,” where scholars presented their findings of the persecution of Christians in some 30 countries:

“[We] cannot subcontract our sense of solidarity with fellow Christians to the government. If we Christians are not on our knees, if we Christians are not mobilizing our parishes, it is a gross hypocrisy to expect our government to do something. If we were to do teachings in our churches, if we were to insist that our priests preach about this issue, if we were to insist that our 'prayers to the faithful' contain not just a phrase but a few sentences invoking God's protection of fellow Christians, we would see these governments acting." In other words, if fellow Christians do not behave as though persecution is a primary concern, why should we expect the world's Ceasars to appropriately value it?

Christians should be valued for their own human worth, as well as their incalculable contribution to modern concepts like religious liberty and tolerance. The West applies legal precepts equally to members of all religions. Freedom of conscience and the inviolable dignity of the individual stand at the heart of 2,000 years of Western intellectual, moral, and philosophical development.

What Kresta’s exhortation amounts to is a call for Western Christians to recover that heritage, and to put it into full effect against the rise of anti-Christian, and anti-human, persecution.

The other essays of this invaluable book demonstrate that this approach has already been effective. The great question before the people of the West is whether we have the strength and wisdom to continue on – or return to – that path. The survival of the Church in the Middle East may very well depend upon it.

(Photo credit: Free Great Picture. Public domain.)