On May 25, Irish citizens will each have the personal responsibility of deciding a question in our fundamental law concerning the natural right to life of other human beings. We have been invited by the Oireachtas (the Irish legislature – R<) to withdraw the present acknowledgement of the right to life of the unborn in Article 40.3.3, to rescind our guarantee to respect, defend, and vindicate that right, and to create an implied right to elective abortion, which the Oireachtas may eventually regulate to some unspecified extent. This should give any rational person pause for thought.

Some people advocate that we should trust others in this matter, by removing the current protection from the Constitution. It may be tempting to follow this advice, rather than engage in the demanding work of reflection involved in any important act of lawmaking. If we value and respect the notion of human rights, which set limits to what the Oireachtas may do in our name, we will rise to this challenge. Citizens cannot outsource this responsibility when human lives are at stake.

It is instructive to review what the Supreme Court has been saying about human rights. The evidence of the past twenty-five years shows that, whatever the people may agree to or reject in a referendum, the Court will tend to neutralise the notion of natural rights mandated by the text of the Constitution, and follow their own preferences in these matters.

This I believe is the nub of the problem. In five instances in the Constitution, two of them enacted in 2012, the personal and family rights that it guarantees are described as “natural” rights. They are said to be recognised, acknowledged, and affirmed —but never “conferred”— by the Constitution. They are also variously described as inalienable and imprescriptible rights, antecedent and superior to all positive law.

This is a very clear affirmation by the people of the principle that our fundamental rights are not created or conferred by a vote in a referendum, but that we owe them to one another as human beings. A “natural” right is precisely one that is inherent in human nature. It does not depend for its origin or authority on any human law, although it requires such laws for its effectiveness. Recognition of such rights is not optional or elective. As the basic rule of justice in society, our Constitution must and does acknowledge and vindicate them.

The Supreme Court, however, has rejected this constitutional affirmation of an objective basis for natural rights. Despite a generation of supportive judicial observations, they held in 1995 that “the courts … at no stage recognised the provisions of the natural law as superior to the Constitution.” Citing a supposed incompatibility between an inherent human law and the sovereignty of a democratic state, the Court has nullified the constitutional text in this respect.

The principle of objective natural rights was explicitly acknowledged once more in 2012 by a sovereign decision of the people. The text of the new Article 42A twice affirmed an inalterable basis in human nature for the rights of the child. On the “positive law” principles adopted by the Court itself, this should have been sufficient to reverse their 1995 policy decision. If the people reject a judicial policy and insist on acknowledging a “natural and imprescriptible” standard for human rights, the Courts must accept and abide by that. That is what democratic sovereignty means.

We cannot validly make laws that go against our human nature, to the extent of depriving our fellow human beings of their basic natural rights.

Not so, apparently. In a recent case on immigration and unborn rights, known as the “M” case, the Supreme Court completely ignored the “natural and imprescriptible rights” in Article 42A and reaffirmed their 1995 decision on the source of constitutional rights. Thus, the Court asked itself whether it would be “possible to look at Article 42A.1 as creating a standalone provision conferring rights on children?” Putting the question in this way, it was bound to get the wrong answer. As we have seen, the Constitution does not purport to confer natural rights on anyone; it recognises and vindicates them.

Why is Article 42A significant? In the X case, the Court made it clear that a right to life does not extend to the protection of one’s physical or mental health. Every living human being, therefore, also needs a basket of other protective natural rights. These include the right to developmental health and well-being; the right not to be poisoned, abused, neglected, or have pain inflicted unnecessarily; and so on. The wide terms of Article 42A.1 clearly acknowledged such rights and guaranteed to vindicate them for “all children.”

The natural rights due to a born child can also be enjoyed by, and are therefore due to, the same child before birth. To hold that human rights suddenly become “natural and imprescriptible” on cutting the umbilical cord is an irrational superstition. The Court apparently subscribes to this fiction, holding that birth is the “gateway” to constitutional rights. By stubbornly refusing the recognition of natural rights as such, against the plain meaning of the constitutional text, the Supreme Court has expressly denied this vital source of legal protection to the unborn child. It has also emptied it of value for other children also.

The Court held that “it is simply not possible to interpret” the phrase “all children” in Article 42A.1 “as encompassing the unborn. They are separately dealt with in Article 40.3.3 of the Constitution.” This clearly reflects the “positive law” mindset of the Court. The Court had difficulty in seeing “any right contained therein which could avail an unborn child.” This wilful blindness stems, again, from the Court’s rejection of the notion of “natural and imprescriptible rights,” which are reaffirmed in that Article. The denial of the health and welfare protection provided in Article 42A.1 to unborn children has no rational basis in human nature.

To repeal Article 40.3.3 would be to complete the wanton destruction of the very foundations of human rights in our Constitution.

This unjust discrimination reached its nadir in the very stark conclusion of the Court that the unborn child has no inherent or implied human rights whatever, other than the limited right to life set out in Article 40.3.3. If that minimal safeguard is repealed in the forthcoming referendum, and replaced by an implied right to elective abortion, the unborn child will be utterly devoid of any protection in Irish law.

I conclude that the Supreme Court’s stubborn rejection of natural rights undermines and perverts our fundamental law. It appears to acknowledge that the people have an absolute power to make unjust and discriminatory laws. In reality, it leaves the ultimate power in the hands of the Supreme Court, which interprets or ignores the constitutional text as it sees fit.

This is not true law or natural justice. We cannot validly make laws that go against our human nature, to the extent of depriving our fellow human beings of their basic natural rights. The present calamitous policy will remain in force unless reversed by some future Supreme Court judgement. In the meantime, it should inform our decision in the forthcoming referendum.

It leaves me in no doubt that to repeal Article 40.3.3 in such circumstances would be to complete the wanton destruction of the very foundations of human rights in our Constitution, not to mention the countless human lives that would be lost.

This article originally appeared in the April 18, 2018, print edition of the Irish Independent and is reprinted with permission.

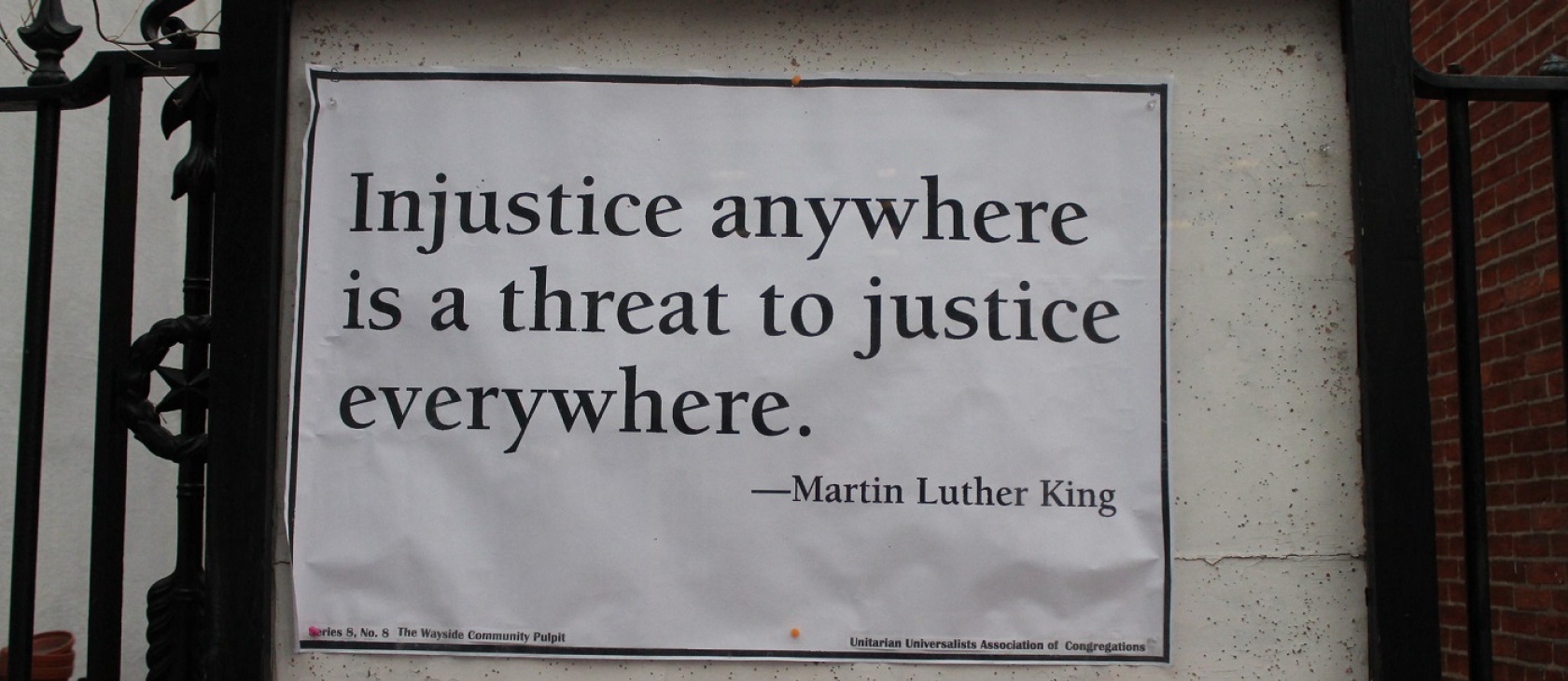

(Photo credit: Evert Barnes. This photo has been cropped. CC BY-SA 2.0.)