Christianity & Social Service in Modern Britain. Frank Prochaska. was published in 2006 by

Oxford University Press. 2006. 228 pages.

Frank Prochaska describes Christianity & Social Service in Modern Britain as “an interpretative study, which seeks to contribute to the history of social service, religious decline, and democratic traditions” (p. vii). There is no doubt that, between the late Victorian years and the twenty-First century, the voluntary provision of social services in the UK was substantially replaced by State provision and, over the same period, Christianity in the UK declined. Frank Prochaska seeks to examine the connection between these two processes.

He does this by first examining the beliefs that underlay nineteenth-century Christian social action and providing a general overview of the nineteenth-century philanthropic landscape, before moving on to consider four specific areas: schooling, visiting, mothering, and nursing. In each case, he examines the motivation, nature, and growth of voluntary Christian action during the nineteenth century and the changes (principally, the decline) that occurred between the last quarter of that century and the years following the Second World War and, to some extent, beyond. In the final chapter, he turns to examining post-war attitudes and endeavouring to draw broader conclusions.

He does this by first examining the beliefs that underlay nineteenth-century Christian social action and providing a general overview of the nineteenth-century philanthropic landscape, before moving on to consider four specific areas: schooling, visiting, mothering, and nursing. In each case, he examines the motivation, nature, and growth of voluntary Christian action during the nineteenth century and the changes (principally, the decline) that occurred between the last quarter of that century and the years following the Second World War and, to some extent, beyond. In the final chapter, he turns to examining post-war attitudes and endeavouring to draw broader conclusions.

These conclusions are damning of UK Christian leaders, especially those in the Church of England. Prochaska suggests that, by the post-war years “The ministerial, civil service state had dislodged civil pluralism, whose foundations lay in Christian notions of individual responsibility” (p. 150) and that “Christian leaders failed to appreciate the consequences of endorsing a collectivist secular world without redemptive purpose” (p. 151). Referring to the Church of England, he comments that “rarely has a British institution so willingly participated in its undoing. The Bishops blew out the candles to see better in the dark” (p. 152).

Bishops and other Christian leaders would do well to reflect on this but they are not the only ones who should pause for thought. The book raises important questions about the impact of the welfare state on moral responsibility, freedom, and democracy. Prochaska’s conclusions should be considered by all those who have enthusiastically supported its creation and enlargement. He asserts that “in what may be seen as the welfare equivalent of urban renewal, comprehensive reconstruction ravaged much of the historical fabric of the voluntary social services” (p. 150) and that, in the post-war years, “Individuals could take satisfaction from paying their taxes, but they were in many ways more impotent in an age of universal suffrage and Parliamentary democracy than their disenfranchised ancestors had been under an oligarchic system” (p. 149).

Prochaska concedes that, to some extent, the landscape has altered in the past 40 years, but he does not believe that the change is fundamental. And he discusses with concern the increasing channelling of government money through charities, suggesting that it undermines the essence of voluntarism. He suggests that “whether a voluntary sector increasingly funded and regulated by government will promote freedom remains an issue” (p. 174).

Those of a left-leaning disposition may well recoil from this kind of analysis, but it would be wrong to conclude that Prochaska is on a crusade against the welfare state. He does not, in fact, analyse the merits and demerits of it. That is not his subject. Furthermore, whilst he clearly has respect for nineteenth-century voluntarism and for what he calls “the religious temper and its role in society and politics,” he is not starry eyed about it. And his comments on the impact of Christianity and its decline come from outside the Church, since he says that he has no personal religious faith (p. vii).

“Christian leaders failed to appreciate the consequences of endorsing a collectivist secular world without redemptive purpose.”

The book has a number of failings. As the quotes above suggest, Prochaska has a penchant for big statements, and many of these are less closely tied to the evidence that he has presented than might be expected of a senior Harvard-based academic. Furthermore, some of his assertions relating to Christianity are misguided. For example, on the basis of his understanding of John Wesley’s theology, he appears to believe that Arminianism had replaced Calvinism within British evangelicalism by the end of the eighteenth century (p. 7), which is certainly not the case.

More seriously, whilst many of the connections he draws between the rise of the welfare state and the decline of Christianity are thought provoking, most readers are likely to be left questioning whether he has truly demonstrated a relationship of cause and effect between the two. The verdict on his fundamental thesis must be “unproven.”

That said, his examination of nineteenth-century voluntarism is fascinating. It will be eye opening to many readers who will have no idea of the enormous scale of Christian (largely evangelical) voluntary endeavor in the nineteenth century. The description of the beliefs and societal structures that underpinned this (including the role of women) is of great importance. Any discussion of the welfare state in the twenty-first century needs to take account of these things if it is to avoid proceeding on the basis of false premises as to what is and what is not possible.

More generally, few people today (whether Christian or not) have a clear appreciation of the extent to which the values and culture of the UK have changed over the past 125 years. In common with most generations, we have a tendency to dismiss our predecessors as ignorant or at least unenlightened and uncritically to equate change and progress. As Prochaska says, “As we reject the pieties and social hierarchies of our ancestors, we tend to forget that benevolence and neighborliness, self-help and helping others, were among the most urgent Christian values. We also tend to forget that much of Britain’s idealism and democratic culture grew out of these values” (p. 2). Prochaska helps us to remember and understand.

What is more, the book is a good read and contains an informative and engaging mix of statistical and anecdotal evidence, the latter bringing the subject to life in a way that mere statistics can never do. Even those who fundamentally disagree with what Prochaska is saying should enjoy reading the book and benefit from doing so.

This article is reprinted with permission from the Centre for Enterprise, Markets, and Ethics.

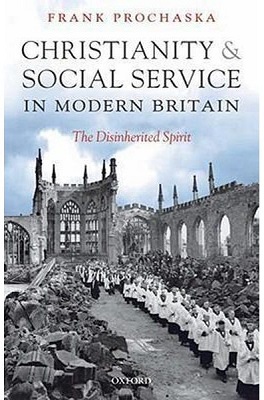

(Photo credit: Acabashi. This photo has been cropped. CC BY-SA 4.0.)