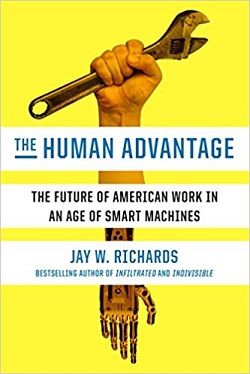

The Human Advantage: The Future of American Work in an Age of Smart Machines. Jay W. Richards.

Crown Forum, 2018. 261 pages.

Catholic University of America business professor Jay Richards has written a humane, economically sound account of the current technological landscape, and argues that coming technological change is no threat to human labor. Labor, Richards argues, will change but not vanish. In contrast to the technophobic discourse becoming increasingly common amongst futurists and financial forecasters, Richards reminds us that the best ways to prepare for the future lie in remembering what makes human beings unique, and then developing the virtues which have sustained civilization for centuries.

The Human Advantage begins with a brief survey of economic history, situating 2018 in a context stretching back to the hunter-gatherers of the Stone Age. He then addresses “the real challenge of our time: the rapid disruption of jobs, firms, ways of life, and whole industries.” In such a world, will “smart machines eat all the jobs?” Richards takes the fear behind this question seriously, but ultimately answers that jobs will not disappear; instead, they will transform. His economic narrative is one of continual disruption. Richards’ explains that ours is the most disruptive economy in history. However, this disruption holds the key to flourishing. Richards argues that no machine will ever contain the virtues which drive human success: “The story of the future is about the five virtues of happy and successful people, each of which matches a feature of the information economy.” Courage, antifragility, altruism, collaboration, and creative freedom are the uniquely human virtues which Richards contends the wise will cultivate to best prepare for this exponentially disruptive market. “Virtue – always the unsung hero of the American Dream – will be more vital than ever in our higher-tech future.” Richards concludes with three chapters meditating on the nature of happiness, the cultivation of virtue, and the differences between human intelligence and machine intelligence.

The Human Advantage begins with a brief survey of economic history, situating 2018 in a context stretching back to the hunter-gatherers of the Stone Age. He then addresses “the real challenge of our time: the rapid disruption of jobs, firms, ways of life, and whole industries.” In such a world, will “smart machines eat all the jobs?” Richards takes the fear behind this question seriously, but ultimately answers that jobs will not disappear; instead, they will transform. His economic narrative is one of continual disruption. Richards’ explains that ours is the most disruptive economy in history. However, this disruption holds the key to flourishing. Richards argues that no machine will ever contain the virtues which drive human success: “The story of the future is about the five virtues of happy and successful people, each of which matches a feature of the information economy.” Courage, antifragility, altruism, collaboration, and creative freedom are the uniquely human virtues which Richards contends the wise will cultivate to best prepare for this exponentially disruptive market. “Virtue – always the unsung hero of the American Dream – will be more vital than ever in our higher-tech future.” Richards concludes with three chapters meditating on the nature of happiness, the cultivation of virtue, and the differences between human intelligence and machine intelligence.

There is a lot to commend about The Human Advantage. The Human Advantage is written to an educated audience, but Richards maintains readability throughout the book. He employs a conversational tone, and tells true stories to illustrate key economic concepts. His writing both educates the reader and prepares the reader to communicate these ideas in a nuanced way. While reading The Human Advantage, one encounters a variety of frequently mentioned economic ideas which Richards dismisses as “myths.” The “lump of labor” myth (which envisions labor as a zero-sum game), the “greed” myth (which argues greed is the foundation of capitalism), and the “follow-your-passion” myth (which argues doing what you love is the best foundation for choosing one’s career) all receive thoughtful treatment and wise rebuttal. His use of economic history draws on common knowledge, and helps the reader put current events into a comprehensible framework.

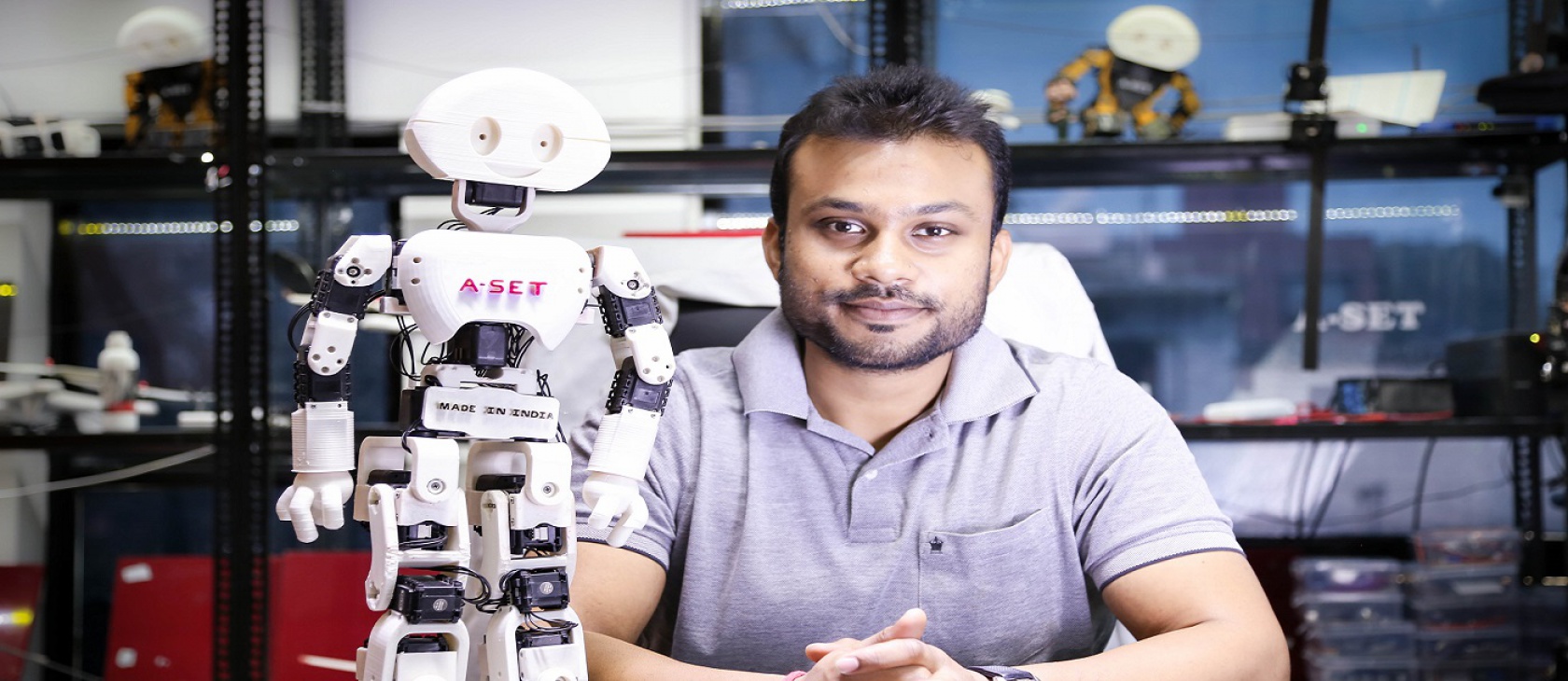

Richards argues that no machine will ever contain the virtues which drive human success.

In Richards’ analysis, we did not simply wake up one morning to discover that robotics have become a real possibility; instead, we are on the growth side of an exponential curve of technological development. He argues, “what’s different about our era is not that technology makes earlier forms of work obsolete but the time scale on which this is happening...In the early twentieth century, we developed mass production, and then, in the blink of an eye, the Information Revolution was upon us.” In the twenty-first century, new technologies arrive, dominate the market, and are themselves replaced by a new innovation within just a few years. In coming years, this speed of change will only accelerate. “The disruption will surely be as profound as it was during the Industrial Revolution, when one form of life replaced another for almost all Americans.” For Richards, these technological innovations are not, at their core, dehumanizing threats to our human activity (work), but the work of the present generation to seek flourishing through stewarding the world.

If there is a weakness in The Human Advantage, it lies in Richards’ reliance on immediately relevant examples. Citing current YouTubers, recent current events, and contemporary technological innovation increases the relevance of Richards’ analysis, but it also makes this book a time-bound volume. Speaking beyond the present historical moment would require substantial revision. It will itself fall victim to the very disruption which it describes; ten years from now, the passages describing the cultivation of virtue for business will resonate, but the pain of the housing market collapse will not speak to readers with the applicability it currently does.

The Human Advantage brings the skills of a professional economist, journalist, and philosopher to bear on a pressing question: Will we have jobs in the future? With the clarity of Thomistic analysis, Richards contends that yes, we will have jobs in the future. They will not look like the jobs of the past, because our world is now a digitally connected, collaborative space with new opportunities; never before have average people had access to the tools and networks which the Information Age places at their fingertips. Richards writes, “An information economy, then, is not an economy where mindless machines take over. It’s an economy shaped by and fitted for us. It’s an economy where human minds, creativity, and freedom predominate. It’s an economy where we purposefully in-form the material and social world in more and more elaborate ways.” Work is not going away, and the best way to prepare for economic success is, in some ways, different (new skills, new ideas, new chances) but is ultimately timeless. Through the practice of virtue, man rises to happiness and, in accord with the “compensatory logic of the universe,” will also find material flourishing no matter what changes arrive.