A Hanukkah meditation.

Suppose you were to stand, clipboard in hand, in the vestibule of your public library and ask the panoply of patrons who pass by to name a fictional character that captures the essence of capitalism. Chances are, the characters mentioned most often would be miserly or unscrupulous, like Dickens’ unredeemed Scrooge, or Gordon (“Greed is good!”) Gecko from the movie Wall Street. While capitalism certainly allows the greedy, the exploitative, and the corrupt to prosper for a while, it also offers vertical mobility for the generous, the selfless, and the exemplary.

Few library patrons recall that entrepreneur Andrew Carnegie funded the construction of some of our greatest libraries – like the New York Public Library, where Leo Astor and Leo Lenox gaze, with serene marble regard, at and beyond the City’s exuberant pandemonium. By the time of his death in 1919, Carnegie had built more than half the public libraries in the United States, some 1,689 structures stretching from Pittsfield, Maine, to Eureka, California; from Pawnee City, Nebraska, to Palestine, Texas; from Redfield, South Dakota, to Jackson, Tennessee.

Capitalism’s detractors, desperate to minimize Carnegie’s generosity, sniff that he built these libraries to see his name displayed across the land. The truth, however, is quite different. Although Carnegie requested something be carved above each doorway, that something wasn’t his name, but rather the Biblical phrase, “Let there be light.” Largely self-educated, Carnegie knew what it was to hunger for light – for wisdom and learning – as a member of a family unable to provide him with a formal education, or even books he could use to teach himself.

Carnegie was inspired to fund libraries by a businessman who let poor boys, including young Carnegie, borrow books from his personal library. Carnegie wrote in his 1869 book The Gospel of Wealth:

When I was a working-boy in Pittsburgh, Colonel Anderson of Allegheny – a name I can never speak without feelings of devotional gratitude – opened his little library of 400 books to boys. Every Saturday afternoon, he was in attendance at his house to exchange books. No one but he who has felt it, can ever know the intense longing with which the arrival of Saturday was awaited, that a new book might be had.

Carnegie focused his entrepreneurial cast of mind on how to maximize his gift’s positive impact. He realized that, important as access to books might be, equally important was having a safe, comfortable, quiet place to read and reflect, cloistered from the screeching squalor of the slums. Thus, he funded buildings where readers could enjoy comfortable, aesthetically uplifting surroundings. Carnegie also reconceptualized the relationship between borrower and book, an approach begun in his libraries and now the norm in most public libraries across American. During Carnegie’s lifetime (1835-1919), books were luxury items, and librarians were charged with protecting these precious artifacts from the page-smudging, spine-bending, ear-dogging fingers of the Great Unwashed. Damage to books was minimized by locking them up in closed stacks, safe from the depredations of curious patrons. A patron wishing to borrow a book would fill out a slip with the requisite identifying information and present it to the librarian, who would then retreat into the stacks and retrieve the desired volume, a practice still employed in the U.S. Archives in Washington, D.C., today.

In Maimonides' framework, the giver removes from the struggling person the humiliating stigma of the supplicant.

Carnegie, however, wanted the books in his libraries to be tools, not artifacts, and was determined to maximize library patrons’ access to as many tools as possible. Carnegie directed his libraries to put the books out on open shelves where patrons could browse, a democratization of consumption analogous to that of the self-service department store, another innovation of Carnegie’s time. Thanks to Carnegie, the lady who browsed the hats in Kaufmann’s Wanamaker’s could now also browse through Booth Tarkington and James Boswell. This change, the product of an entrepreneurial, rather than an academic cast of mind, increased exponentially the ability of Carnegie’s libraries to uplift the lives of patrons. It is little wonder that Carnegie became known as “The Patron Saint of Libraries” by grateful contemporaries.

Unfortunately, gratitude for, and even awareness of, the generosity of Carnegie and other entrepreneurs was nearly exterminated by college professors, education bureaucrats, and journalists infatuated with Marxism and ignorantly contemptuous of the free market. When they did not omit him from American history, Big Education demonized Carnegie as a “Robber Baron,” despite his having done more to help teachers, scholars, schoolchildren, and journalists access information than any other individual in American history.

With the rise of the high-tech economy, which is highly individualistic, competitive, and entrepreneurial, doctrinaire anti-capitalism is fading faster than roller disco did. It is out of the high-tech world that many of today’s most generous philanthropists come. Although its leaders are liberal politically, unlike previous generations of donors, they don’t reject free-market strategies out of hand but rather seek to harness the energy of capitalism, as well as its culture of accountability. Like Carnegie, these philanthropists are thoughtful, strategic investors in human potential, and, like Carnegie, they approach philanthropy in a strategic businesslike manner. These new philanthropists want a “return” on their investment in the form of demonstrable progress toward solving the problem that is their passion. Rather than being satisfied with merely “raising awareness” of a problem, today’s entrepreneurial philanthropist demands and develops pragmatic solutions that can be scaled up to make the desired impact quickly and significantly.

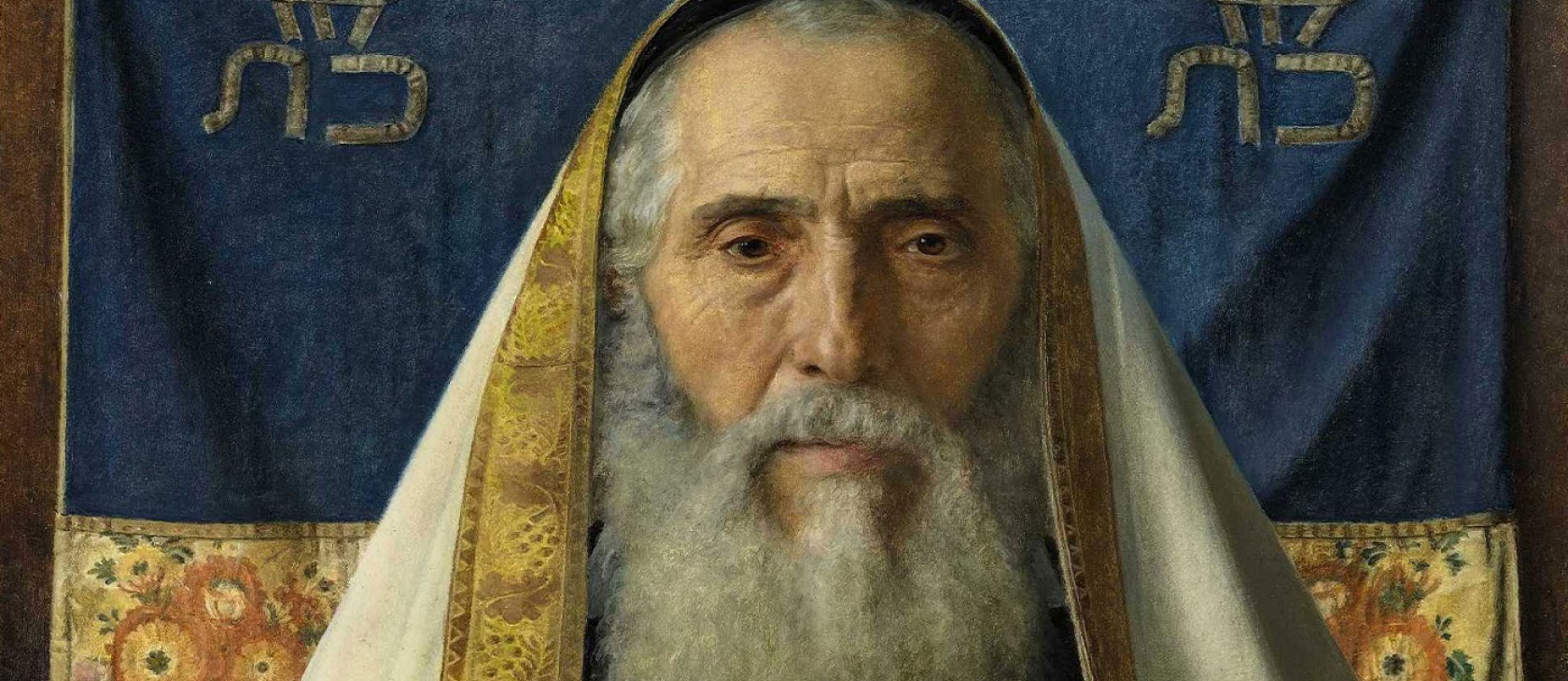

This businesslike approach to philanthropy is at once innovative and ancient. The medieval rabbi and philosopher Maimonides, for example, established a hierarchy of criteria to rank the quality of one’s gift. The concept about which Maimonides wrote wasn’t charity, which is a kind of virtue, but tzedakah, which, though commonly translated as “charity,” means something closer to “justice” or “righteousness.” For Maimonides, giving isn’t a virtue for which you are to be commended, but an obligation presented by our Creator, as a steward, not the owner, of His property. And for Maimonides, all giving is not created equal: a gift’s value in the eyes of the Creator depends on the circumstances under which it’s given, the spirit in which it’s offered, and its potential for what we now call “sustainability.”

Maimonides ranks the quality of giving thus, from minimally virtuous to maximally virtuous:

8. You give, grudgingly.

7. You give less than you should, but do so with a generous spirit.

6. You give to someone in need, but they had to ask you for help. (They shouldn’t have to ask.)

5. You give without being asked, because you see a need. You know whom you’re helping, and they know you’re helping them.

4. You don’t the party who will receive your gift, but the recipients know you are their benefactor.

3. You know whom you’re helping, but they don’t know you are helping them.

2. You give without knowing the recipient, who benefits without knowing your identity.

1. The highest form of charity is to help a person find employment or start their own business.

What a remarkable, refreshing idea: that the highest form of charity is to help talented people find employers who value them, or to become business owners themselves, and thus, potentially, employers of other people in need of work. The giver removes from the struggling person the humiliating stigma of the supplicant. He offers an endorsement of the recipient’s talent and character in the form of recommendations for positions or offers of capital to enable the person to start his own business venture. A time of struggle and despair can be transformed into a time of growth and pride. And she who is raised up by such trust in her talents may well replicate that experience for others down on their luck, and those she benefits may do the same. Such entrepreneurial philanthropy may well generate a kind of multiplier effect that uplifts, not only an individual’s income and his heart, but ultimately generations within his community.

This possibility of replication suggests that there may be a level of charity superior even to that Maimonides ranks highest; perhaps the truly highest kind of giving is that which inspires others to develop a charitable spirit and provides the analytical framework necessary for giving to achieve maximal effect. Such philanthropy Maimonides has extended to the world for nearly a thousand years.

Andrew Carnegie well deserves to be called the Patron Saint of Libraries.

And if anyone would like to nominate a nice Jewish boy as the Patron Saint of Venture Capitalism, Maimonides certainly has my vote.

Further resources from the Acton Institute on Judaism and economics:

Judaism, Law & the Free Market: An Analysis by Joseph Isaac Lifshitz

Judaism, Markets, and Capitalism: Separating Myth from Reality by Corinne Sauer and Robert M. Sauer