John Foster Dulles was Dwight D. Eisenhower's secretary of state from 1953 to 1959. In the tense, early years of Cold War politics, Dulles pursued a foreign policy designed to isolate the Soviet Union and undermine the spread of Communism.

In the following video, professor John Wilsey speaks about his research into one of the most influential figures of twentieth-century politics – and how the decisions Dulles made years ago still have consequences for us today. The video and full transcript of his remarks are below.

Transcript

[00:00:00] Dan Churchwell: [00:00:00] Well good afternoon, and welcome to the Acton Institute. We're delighted you're here!

[00:00:09] To introduce, I'm here to introduce our speaker for our February Acton Lecture Series. My name is Dan Churchwell and I'm the director of program outreach here at the Institute. And it's with great pleasure I have to introduce a friend at this one.

[00:00:25] John Wilsey and I have known each other for about three and a half years now. We've traveled the country. He is an affiliate scholar with Acton, which means a lot of our events, he comes and speaks on many different topics in the realm of history, church history, American history.

[00:00:41] Let me read the formal part. John Wilsey is an affiliate scholar here at the Acton Institute. He is an associate professor of church history at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville. Did I say it right? Thank you. He's the author of multiple books, including the American Exceptionalism [00:01:00] and Civil Religion: Reassessing the History of an Idea with IVP Academic. He also edited Alex- Alexis de Tocqueville's famous work, which recently appeared under the title Democracy in America: A New Abridgment for Students. And he speaks widely on Alexis de Tocqueville. And he was also in the year 2000 - 2017 and 18 a William Simon visiting fellow of religion and public life at the James Madison Center at Princeton University.

[00:01:31] He has currently finished his research on John Foster Dulles. The current biography is now with the press and should be released in a few months. So that's one thing off of his plate. But it's a delight; I've traveled, like I said, all over the country with him. He has a wide base of knowledge, and we also love the great state of Montana, hiked many of the same places together. So without further ado, please welcome Dr. John Wilsey.

[00:02:04] [00:02:00] John Wilsey: [00:02:04] Well, thank you very much, Dan, for that wonderful introduction. And Dan and I have have indeed traveled the country together. One place that we went to very memorably was in Alaska, which was one of my favorite trips that we took.

[00:02:19] But thank you so much for inviting me. Thanks so much for, this, this great event. I appreciate the invitation so much from the Acton Institute and this is such a fascinating topic and a fascinating guy. Let's see if I can get this sludge show going here. There we go. There's the title page there on John Foster Dulles.

[00:02:41] I couldn't tell you much about the weather on March 19th, 2018 except that it was cold. I'd spent most of the day in the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library at Princeton University going through folder after folder containing documents and pictures pertinent [00:03:00] to Dulles' life in the late twenties and thirties. About 20 minutes before closing time, I decided to open one more folder and then pack up and head home.

[00:03:11] The folder contained some photographs from 1933. It was a thin folder; just a few pictures to look at, I thought, and then I could stretch my legs and give my bleary eyes a rest. The photograph contained in that folder gave me a start. It showed a large reception room filled with people. The people in the photo were dressed in formal attire. They were smiling, enjoying conversation, making their rounds to friends and associates around the room. Here, a young woman is wearing a hat. She's smiling warmly. Perhaps she's meeting someone for the first time, introducing herself. And there, a man looks to be making his way through the press of people, perhaps trying to catch someone on the way out with a greeting or to get some quick clarification [00:04:00] on a question.

[00:04:01] Everyone in the photo looks to be enjoying themselves. It's a party. A notation on the back of the photograph simply says, JFD 1933. And right in the center of the photograph among all the partygoers in the room is the unmistakable face of the then German chancellor Adolf Hitler.

[00:04:24] In the photo, Hitler is dressed in a white tie and tails, as you can see. If you look carefully at his lapel pin depicting the Nazi party insignia is proudly displayed there and his, on his coat. And there he is talking to John Foster Dulles with his back turns, turned toward the camera. The broad smile on Hitler's face as he talked with Foster demonstrates that he was relishing the moment.

[00:04:50] This is one of those times in the archive that sends the blood running so quickly through your body that you can hear your own heart beating. Up to this point, I had no idea that Foster had ever [00:05:00] met Hitler. I had not seen any other biographers mention it. His brother, Allen, had met Hitler. One biographer described how Allen had met Hitler on an official visit to discuss Germany's massive, outstanding World War I debt reparations, at Nazi party headquarters in the early thirties. Allen cracked a joke with the Fuhrer about the British and the French. And at first Hitler didn't get it, but then when someone explained the joke to him, he broke out into loud guffaws. Allen said later that, quote, "Hitler had a laugh louder than Foster's. I always thought my brother brayed like a donkey when he laughed, but now I know he sounds like a turtle dove compared with Hitler."

[00:05:44] The mystery of Foster's meeting with Hitler in 1933 was deepened by the fact that the photograph has no notation except for "JFD 1933." But a few days later, I came across an unreleased statement from Foster. It was dated many years [00:06:00] later - January 21st, 1952. It said, quote: "I was in Germany in 1933 as representative of American bondholders to induce the German government to resume payment on us dollar bonds. I never had any discussion with anyone anywhere with reference to supporting Hitler, who's coming into power in Germany I deeply deplored." The statement was helpful in providing some needed context for the photograph, but in many ways it raised more questions than it answered. Why was Foster in Berlin in 1933? What was he doing meeting with Hitler? Was he a Nazi sympathizer? Was he an anti-Semite? Was this the only meeting that Foster had with Hitler or were there others? Why did Foster not release this statement to the public? Where was the nature of, what was the nature of his ties to Nazi Germany? What does this meeting, shrouded in [00:07:00] obscurity, say about Foster's religious, political, social, and personal convictions? And then there is the cynical question I tried in vain to suppress, but it persisted in crowding up all this space in my mind: was Foster hiding something?

[00:07:18] As I continued to collect resources, I learned more about Dulles' 1933 visit to Berlin. I discovered that he was accused by some fairly prominent figures many years later of divided loyalties in his dealings with Germany in the 30s. And it occurred to me that the work of writing a biography, and in this particular case, a religious biography, is fraught with the biographer’s peril of having very, very much power over the subject, a power accompanied by the risk of failure to appreciate the responsibility of wielding that power.

[00:07:55] Now the subject of the biography is John Foster Dulles, Eisenhower's Secretary of State [00:08:00] who towered over American foreign policy like a Colossus from 1953 to 1959. He was born in 1888; he died in 1959.

[00:08:12] As a Christian historian, I'm bound to sort of approach the craft of writing history with the teachings of Christ in the forefront of my mind, especially the teachings in the New Testament about the fruit of the spirit. So I'm cognizant of the fact that we have a perspective on the scope of Foster's life that he didn't ever have and his friends didn't have, and his family didn't have it. Nobody had. Even his enemies, you know, who, who dug dirt on him, didn't have the kind of perspective on the scope and sweep of Foster's life that, that you and I have. When he died in 1959, he was buried at Arlington Cemetery. It was followed - it was, the, the funeral was followed [00:09:00] by a state funeral, which was the largest state funeral in the history of the capital of our nation up until John F Kennedy's funeral in 1963.

[00:09:11] When I consider the photo from 1933 showing Hitler having a laugh alongside Foster and all the questions that it raises, I remember that I possess the power of knowledge. I know the details of what to them is the uncertain future. I know what Hitler will go on to perpetrate against humanity. I also know how Foster will react to Hitler's actions in future years, how World War II will shape Foster's most profound convictions - things he could never have known then.

[00:09:47] And finally, I've access to knowledge about the consequences of decisions that Foster made as a central figure in the 20th century. Many of those consequences continue to have their effects today. [00:10:00] And we are all compelled to live with those consequences, whether we like it or not. Foster could never dreamed of having such knowledge and perspective. In short, when it comes to a life like Foster's, in some sense, you know, we know the end from the beginning. We don't know everything. We're still just people. Our knowledge is limited. But we have vast access to stores of evidence from his entire life. As we look back on Foster's life as he lived it from 1888 to 1959, we have a perspective that of course he could never have, and thus we have a decided advantage over Foster.

[00:10:41] And this advantage translates into another kind of power, the power to render moral judgment on him. Historian Beth Barton Schweiger reminds us to use this power responsibly. We do not shrink back from critical moral evaluation of a life like Foster's. But we do remember that- to do so [00:11:00] circumspectly. Just because our historical subject is dead does not mean he loses his humanity. And just because he's dead does not mean that his living students are omniscient, or immune to their own moral failings and limitations.

[00:11:18] So who was he? There's an irony to this question. To a certain extent, this question should be unnecessary. The name John Foster Dulles during the 1950s was a household name. That wasn't that many years ago. Many folks of a certain age can call him to mind quite readily. But still it seems that today, many remember the name of Dulles only in association with an airport being named after him.

[00:11:49] When Foster died on May 24th, 1959, the whole world mourned him. His state funeral, as I said, was the largest state funeral in Washington's history [00:12:00] since Franklin Roosevelt's in 1945, and surpassed only by Kennedy's a few years later. Dwight Eisenhower, his president, wrote that he was a, quote, "champion of freedom." He said he was a foe only to tyranny, and one of the truly great men of our time. "No one," said, said Eisenhower, "has the technical competence of Foster Dulles in the diplomatic field." Eisenhower said this about his secretary of state in 1956.

[00:12:31] Most Americans of the Eisenhower era agreed. In the spring of 1953 only 4% of Americans disapproved of Foster's handling of his job in 1962 a few years after Foster's death, President Kennedy dedicated the newly completed commercial jet airport on 10,000 acres of land outside of Washington as Dulles International Airport. Kennedy praised Foster and the entire Dulles family in his speech [00:13:00] for their tradition of committed service to the United States at the highest levels.

[00:13:06] But over time, since that time, Foster's star has fallen. At the airport dedication ceremony that Kennedy presided over, an unveiling of a, uh, uh, of an imposing bronze bust of Foster was, was introduced. After about three decades, though, the bust was removed, and stored away to prepare for extensive renovations, and it was never replaced. Its removal was to the chagrin and irritation of, well, nobody. One of Foster's recent biographers, Stephen Kinzer, found the missing bust stashed away, in an obscure conference room, as he said, "looking big eyed and oddly diffident, anything but heroic." By the early seventies, many of Foster's biographers began to cast him as [00:14:00] an overbearing Presbyterian, an arrogant and obstinate simpleton, a man with a binary view of the world, uncritically regarding Americans as the good guys, and the communists as the bad guys. In 1981 the editors of American Heritage ignored Foster when they compiled their list of the 10 best secretaries of state in American history. And by 1987, Foster was ranked as one of the five worst secretaries of state in American history.

[00:14:35] Foster's star has fallen to the extent that today he has come to serve as a scapegoat for American foreign policy failures of the fifties and sixties and seventies. Kinzer, for example, is a biographer with no use for subtlety in his contempt for John Foster Dulles. In a 2014 interview he- on his dual biography of Foster and Allen, Kinzer hissed that [00:15:00] Foster was, quote, "very off-putting. He was arrogant, self-righteous, and prudish. Even his friends didn't like him." Kinzer drops the entire burden of responsibility for the Vietnam debacle squarely in Foster's lap. "John Foster Dulles," Kinzer said, "was more responsible for the U S involvement in Vietnam than any single individual." To drive the point home, he said "we could have avoided the entire American involvement in Vietnam absent Foster's decisions at the Geneva conference in 1954." That's saying a lot.

[00:15:46] Speaking of that, on May 7th, 1954, Ho Chi Min and his Viet Minh forces overran the French Citadel of Điện Biên Phủ in Northern Vietnam, as the French took their last stand in a long and [00:16:00] costly conflict to maintain control over their colonial possessions in Indochina. Ho's victory meant that he would have serious credibility representing Vietnamese communists at the Geneva conference, meeting during the late spring. With impeccable timing, his forces defeated the French shortly after the conference had gotten underway. All but one of the involved powers - the United States - agreed that given the combination of Ho's popularity among the Vietnamese people and raw staying power, resisting him would be all but futile. Ho would be negotiating with the anticommunist Vietnamese representatives as well as those from Cambodia, Laos, Britain, France, China, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

[00:16:48] Foster led the American delegation at Geneva. His primary attention was on establishing a lasting peace on the Korean peninsula after the conclusion of the armistice that ended the Korean war in [00:17:00] 1953. He maintained that he would have nothing to do with any compromise at all with the communists on the future of Vietnam.

[00:17:10] Foster was unabashedly contemptuous of the Chinese communists and was convinced that Ho Chi Min was a Chinese puppet. And he was confident that America could succeed in building up an anticommunist bulwark in Indochina where the French had failed. At a London press conference held prior to the conference on April 13th, 1954, Foster had the following exchange with a reporter. The reporter asked, "what would you regard as a reasonable, satisfactory settlement of the Indochina situation?" Foster replied, "the removal by the Chinese communists of their apparent desire to extend the political system of communism to Southeast Asia." The question, follow up: [00:18:00] "that means a complete withdrawal of communists from Indochina?" Foster said, "that is what I would regard as a satisfactory solution." Follow up question: "is there any compromise that might be offered if that is not entirely satisfactory to the communists?" Foster's response: "I had not thought of any."

[00:18:24] Foster's intransigence continued into the conference. When a reporter asked him two weeks later in Geneva if he planned to have any private conversations with the Chinese foreign minister Zhou Enlai, Foster's dry response was: "not unless our automobiles collide."

[00:18:45] Foster was committed, first and foremost, to American national security against what he saw as an aggressive, expansionist, totalitarian, communist regime, and he made no apologies for his inflexibility. In later years, [00:19:00] Foster's style was considered to be pig-headed, dangerous, and the result of religious fanaticism.

[00:19:08] Foster was a man of many ironies. He was a private man, preferring the company of his wife, Janet, and his poodle Peppy, over anyone else. He kept his inner life largely hidden from outsiders. And moreover, the world that he shaped and was shaped by was deeply complex. The historians who know him best consistently describe him as an elusive figure, a very difficult man to pin down. Simplistic pronouncements distort our understanding of both the man and his times.

[00:19:45] Foster was one of the longest serving secretaries of state in the history of the department, serving from January of 1953 until his death, or just before, a month before his death, in April of 1959. His [00:20:00] experience in international politics began remarkably early. He was 19 years old and finishing his junior year at Princeton University when his grandfather, John W. Foster, invited him to attend the second Hague Convention in 1907. Grandfather Foster was serving as representative of the Chinese government, and young Foster went along with his grandfather as his private secretary.

[00:20:28] He served on many subsequent diplomatic missions, representing the United States to Panama in 1917, to the Versailles conference in 1919-20, to London and Moscow in the immediate years after World War II, and the first sessions of the United Nations general assembly. His most notable foreign policy achievement prior to his tenure as secretary of state was his negotiating the treaty of peace with Japan, between the years 1950 and 51. It was a triumph. [00:21:00] His leadership was so effective that President Truman offered him the post of ambassador to Japan. But preferring not to be, as he said, "at the end of the transmission line, if the powerhouse itself was not functioning, but rather at the powerhouse," Foster turned him down, and became Eisenhower's choice to head the department of state.

[00:21:23] Foster's diplomatic experience was direct- was directly related to an aspiration he had as a young man to be what he called "a Christian lawyer" in the mold of his grandfather, John W. Foster. John W. Foster served as secretary of state under Benjamin Harrison from 1892 to 1893. One evening in the summer of 1908, shortly after graduating as valedictorian from Princeton, Foster was having a conversation with his parents about his career plans. He had seriously considered becoming a minister like his father. But in the end, [00:22:00] he decided against it. "I hope you will not be disappointed in me if I do not become a minister", he said. "But I've thought about it a great deal, and I think I could make a greater contribution as a Christian lawyer and a Christian layman than I would as a Christian minister."

[00:22:17] Foster blended his vocation as Christian lawyer with that of diplomat in order to serve his country, but also to serve his church as he understood it. In 1937 he attended the Oxford Ecumenical Church Conference. Prior to attending that conference, Foster despaired of the church ever having any real effect on world problems. But the meeting inspired Foster. He became convinced that Christianity was the fount from which the solutions to all of humanity's problems just bubbled forth. As a 54 year old looking back on his thirties, the fruitful years of his career as an international [00:23:00] lawyer, he wrote a short piece called, I Was a Nominal Christian. He said, "I became only a very nominally, very nominally a Christian during the succeeding years." But then after the Oxford conference, Foster realized that the spirit of Christianity, as he said, he said "that which I learned as a boy was really that of which the world now stood in very great need, not merely to save souls, but to solve the practical problems of international affairs."

[00:23:35] So when I write this, when I wrote this biography, it considered Foster's religious commitments, and how he articulated them during his life as a churchman, as a lawyer, and then later as a diplomat. He regarded his religion as the animating force of his life, particularly during his public career. He was brought up in a devout Presbyterian home, [00:24:00] son of a, of a pastor, Allen Macy Dulles, the pastor of the First Presbyterian Church at Watertown, New York. Both his mother and father instilled in Foster an abiding confidence in the ethical teachings of Christianity.

[00:24:16] Foster's religious commitments ebbed and flowed during the course of his life; he was not always devoted to the faith that he learned from his childhood to the end of his life. But his Presbyterian upbringing established attitudinal patterns. His faith commitment lay - his faith commitment lay somewhat dormant in his early adulthood, but it awakened into a sharply articulated and developed form in his middle to late career.

[00:24:45] This is a picture of the First Presbyterian Church in Watertown, New York, still standing, and this is how it looked when Foster was a boy and his father was the pastor for 17 years.

[00:24:56] Foster's religion can be succinctly described as liberal [00:25:00] Protestant. Although to be fair, he held several conservative attitudes and practices as well. Most importantly, Foster put the practical always above the abstract. For him, the dynamic change in history always prevails over the static. Change, not continuity, was the normative feature of time. And moral forces - what he called moral law, what he called natural law, in sort of a liberal Protestant way of thinking, the power of right over wrong - these forces were invincible.

[00:25:39] The churches were indispensable also to maintaining world peace. Peace, like war, must be actively waged to be secured and advanced. He believed that America was chosen by God to actively champion and defend human freedom, and protect peoples who were [00:26:00] vulnerable to tyranny, mainly communist tyranny.

[00:26:04] God's providence was prominent in Foster's thinking. He understood America's mission in terms of Christ's teaching of the parable of the faithful servant that to whom much is given, much is required. And he believed that God had given him the special purpose of calling Americans to the national divine mission.

[00:26:27] He thought theology had its place in the pulpit, but the essence of Christianity according to Dulles, was operational, not dogmatic; ethical, but not theological. In short, Foster's Christianity was fortified with American values and a hands on religion, a religion stressing the importance of duty, one that solves everyday problems, and one that gives human dignity and freedom, the highest prominence.

[00:26:58] There's another element that formed [00:27:00] his religious and intellectual worldview, and that was nature. From a very early age, Foster developed a love of the outdoors. His grandfather, his uncle, Robert Lansing, who served Woodrow Wilson as his secretary of state, both owned houses adjacent to one another at Henderson Harbor on the Ontario shore in upstate New York, just 20 miles or so from Watertown. And these houses form something like a family compound. And from his earliest years, Foster joined the family as they spent their summers, from May or June, all the way through September, living at the compound, fishing and sailing and camping and reading and all kinds of outdoor activities.

[00:27:45] Early in his life, Foster cultivated the skill of sailing. As a boy, he had a small craft he named Number Five. As an adult, he enjoyed taking long cruises on his 40 foot yawl, the [00:28:00] Menemsha. He took his children sailing; taught his, both of his sons to sail. They cruised as far West as Lake Superior, as far East as Long Island Sound.

[00:28:11] Avery Dulles, Foster's son, who grew up to become a very prominent Catholic theologian, in particular loved to sail, and was a very quick study. Avery recalled how his father had taught him to navigate by dead reckoning, and that he had once navigated successfully across the Bay of Fundy, with his father, in a thick fog.

[00:28:37] A number of biographers cast Foster as something of a cold and distant father. One biographer, Townsend Hoopes, who wrote a book called The Devil and John Foster Dulles - it tells you something about his perspective - wrote that Dulles- that Foster's three children, quote, "were classic cases of parental neglect." [00:29:00] But what cold and distant father teaches his son to navigate a sailing vessel across the Bay of Fundy by dead reckoning? Avery said later, it was one of my great triumphs - he was only 12 years old - as he described navigating against the powerful current and a fog so thick that visibility was down to just a few feet with his father Foster at his side.

[00:29:29] In addition to sailing, Foster owned an Island in Lake Ontario called Main Duck Island. He and his wife, Janet would spend weeks at a time on, on Main Duck in a cabin that he had built by local Indians with no plumbing, no electricity, no direct contact with the outside world. He loved the outdoors. He consistently saw nature as a classroom for learning how to navigate difficult problems in diplomacy. His the idea of moral forces he extended to natural forces. [00:30:00] So sailing through a storm in the middle of the Great Lakes, he saw as being a metaphor of some sort to the challenges of international diplomacy.

[00:30:11] He also cultivated connections with the local folks, Canadian fisherman on the lake, often buying their fish from them, giving them access to the waters surrounding his Island. One fishermen by the name of Herbert Cooper was a fisherman and a teacher, is, he's still alive. But he was a teacher for many decades, and a fishermen from Prince County - Prince Edward County in Ontario. He recalls how Foster maintained good relationships with all the Ontario fishermen earned their respect and their admiration.

[00:30:46] Herb Cooper was a guest of Foster and Janet on their Island when he was 18. They had dinner together, and Mrs. Dulles would not let him join Foster in a round of Old Overholt, [00:31:00] which was Foster's favorite rye whiskey. She said to Herb, "you're too young." And she gave him a cup of hot tea instead.

[00:31:11] So these details describing Foster's family relationships, his religious upbringing, his love of the outdoors, these are all essential to understanding the man, not just as a diplomat or a churchman or lawyer. He was famous for his love of a good joke. His laugh was legendary as it was contagious. Associates and friends describe him as laughing all the time, throwing his head back and roaring a laugh that reverberated throughout the room. Those that worked for him had a particular affection for him because he treated them with respect and with dignity and with affection. His secretary, when he was secretary of state, Phyllis Bernau Macomber, she described everyone in his office as a family. They worked to exhaustion, [00:32:00] traveled with him all over the world, and saw him at his best, and at his worst.

[00:32:06] Macomber was so devoted to him that she waited by his bedside in the last weeks of his life as he was dying of colon cancer. One evening as he laid in his hospital bed, just before his death, he invited her to move on, to leave the staff if she saw him as something of a falling star. She said, "I said, no, I was going to stay. That was it. I wouldn't think of doing otherwise." Foster's humanity is most clearly evident to those closest to him, and especially those who worked under him.

[00:32:46] But at the same time, Foster could be calculating and cunning. As indicated above, Foster had close business ties to German industry and finance in the 30s which brought him into contact with Hitler. Since Foster was not a public [00:33:00] figure during the 30s, his activities escaped wide notice. But in 1944, when it was evident that a, if Thomas Dewey were to win the presidential election of 1944, that he would pick Foster to be his secretary of state, this brought Foster into the public eye.

[00:33:19] A muck raking journalist by the name of, uh - oops. That was, that's uh, uh, Phyllis Macomber. That was his secretary. That was a slide I should've showed you a second ago. There we go.

[00:33:34] A muckraking journalist named Drew Pearson wrote a number of pieces calling Foster's activities into question, most notably his relationships with cartels and banks that did business with Nazi Germany. "Right up to the outbreak of the war in 1939," Pearson wrote, "John Dulles took the attitude that Germany was a misunderstood nation, which had often shown great investment promise, [00:34:00] and now should be treated with sympathy and understanding until she got back on her feet." Foster did in fact defend Hitler as late as 1937 against those who considered him a warmonger and a lunatic. In a letter to the editor of the Forum magazine at the time, Foster Wrote:

[00:34:20] "One may disagree, as I do, with many of Hitler's practices and policies. But such disagreement should not lead one into the error of disparaging his abilities. One who from humble beginnings, and despite the handicap of an alien nationality, has attained the unquestioned leadership of a great nation, cannot have been utterly lacking in talent and energy and ideas."

[00:34:45] It's also true that Foster was reluctant to close his law firm's Berlin office after Hitler had come to power in 1933. Foster was the only voice among the firm's partners that advocated for keeping the Berlin [00:35:00] office open. He was worried about the financial loss that result from such an action. He said, "what will our American clients think? Those whose interests we represent in Germany? If we desert them, it will do great harm to our prestige in the United States." Only after the colleagues at the firm threatened to quit and form a competitor firm did Foster finally relent. And in a meeting called to consider moving out of Germany, faced with rebellion from the other partners, Foster finally said, "who is in favor of closing down an operation in Germany?" Every single hand was raised. Foster said, "then it is decided. The vote is unanimous."

[00:35:45] Still, when he was subjected to criticism in the 40s during the beginning stages of his public career, Foster consistently boasted that he had led his firm to leave Germany once Hitler had established himself in power. He wrote in [00:36:00] 1946: "my firm's attitude toward Hitler can be judged from the fact that promptly after Hitler's rise to power, my firm decided as a matter of principle, to act- not to act for any Germans. That was in 1935, several years before our government broke with Hitler." Twisting the narrative to favor his own role did not seem too problematic for him.

[00:36:28] Foster could claim with credibility to have no direct association with Hitler's government, but it was also true that he maintained ties to powerful men- mineral and chemical cartels that did business with Germany. Foster was a director of the Consolidated Silesian Steel Company, which owned stock in the Upper Silesian Coal and Steel Company, which fueled the German war machine.

[00:36:56] Foster always vehemently denied that he was in any way a [00:37:00] supporter of Nazi Germany. He consistently distanced himself from any ties to Germany during the 30s. And when he was scrutinized, not only by the media, but other figures ranging from United States Senator Claude Pepper of Florida, to everyday church people, pastors around the nation, the question of his attitude towards the Nazis was brought up again and again. As Dulles' biographer, Ronald Pruessen reminds us, these matters are fraught with, with their own complications and complexities. While Foster's denials of direct association with German businesses that strengthened Hitler were technically true, he still maintained indirect ties with those interests all the way up until the outbreak of the war. Ronald Preussen wrote: "A far more accurate gauge of the sentiment of American businessmen toward Germany in the 30s is a measurement of their actions rather than their words." And [00:38:00] this is certainly true of John Foster Dulles.

[00:38:04] If we can say anything certain about Foster as we evaluate his life, we can say that he was a person who had many paradoxes and ironies. Personally, he was known for being principled, but he was eminently pragmatic. He was devoted to his children, but he was often distant and hard on them when they disappointed him, he could be a father figure to his siblings, and at times a sibling figure to his children. He was witty and gregarious, but he was also withdrawn. He boasted that he knew the Bible better than anybody in the State Department, but he rarely read the Old Testament. He was proud and vain, but he also welcomed opposing ideas and was always open to criticism. He was adventurous, but he was not athletic. [00:39:00] He loved to expose himself to danger, but his idea of a good time was an evening of backgammon with his wife, and a good mystery novel. He inspired lifelong loyalty, devotion, and affection from his friends who did like him, but his Princeton classmates had no real recollection of him when asked about him decades later.

[00:39:27] He was scholarly, and erudite in legal and diplomatic matters, but, but rather incurious when it came to private reading and study. He could be urbane and sophisticated, but he also loved simple things, like getting a free haircut when he was a US Senator. He enjoyed wealth and power, but he never lost touch with his provincial, upstate New York roots. He loved competition, but rarely competed in sailing or tennis, which were his favorite sports. [00:40:00] He was devoted to his wife, but encouraged his sister not to marry her partner because he was Jewish. He readily broke from the ministerial tradition of his family, but he personally struggled when his own children charted their own paths away from other Dulles traditions. He was rigid and stubborn. But he often changed his mind on issues of religion and diplomacy. He was sensitive and gentle with his staff, but he drove them hard, and he inspired awe and fear among them.

[00:40:36] He was an introvert, but he loved the campaign trail. He loved press conferences. He was a tireless worker, but he was home every night for dinner and games with his wife and children. He was serious and grim, but he had a hilarious laugh and a quick sense of humor. In his public life, he was a [00:41:00] man of overt religiosity, but not what you would call a prayer warrior. He preached a developed argument for natural law, but he was not a theologian. He was a committed internationalist, but he believed in American indispensability. He was suspicious of alliance systems, but constructed them all around the world to isolate the communists. He admired the dynamism of communism; he recognized it as a religion in and of itself, but he condemned it as godless, and he committed himself to its eradication. He was disparaging of those whom he saw as a reacting emotionally to the Nazis and the 30s, but he himself was uncritically and unstintingly opposed to the communists after 1945.

[00:41:47] He favored international control of atomic weapons prior to becoming secretary of state, but as secretary of state, he advocated for a strategy he called "massive retaliation," [00:42:00] and dared America's enemies to go to the brink of nuclear war. He gave us a lasting and just peace with Japan, but he had little imagination to fashion a similar peace with the Chinese or the Soviets. He was a political operative, but not a politician. At various points during his career, he was accused of being both a warmonger and a pacifist.

[00:42:25] He lacked public charisma. He was bland behind a podium, but he had a magnetic presence in the room. He was tall. He was muscular. People were attracted to him. Women were frequently drawn to him - but he was famously ardent and devoted in his love and attention to his wife.

[00:42:47] Louis Jefferson, Foster's bodyguard while he was secretary of state, reflected on how Americans viewed him. Nearly 30 years after his death. "History has put a cold [00:43:00] face on John Foster Dulles," he said. "The image we are given is more often than not inhuman. Yet Foster Dulles was, if nothing else, a very human man." There's no better way to describe Dwight Eisenhower's secretary of state. Part of the reason that the popular image of the dour Puritan endures is simply that Foster projected that very image to the world.

[00:43:27] He was serious; he was thoughtful - someone who drew a hard line separating the personal from the professional, the trivial from the substantial, recreation from industry, and the joviality from solemnity. But his religious upbringing, his religious ideas, motives, imagination, rhetoric, and practices, for what they were worth, offer us a window into the man. John Foster Dulles' humanity, [00:44:00] animated by his religion, is the subject of what I wrote in my biography, and the subject of this talk. And understanding Foster in this way, you and I can come closer to grasping our own humanity. And in communing with the dead, perhaps we can come to a further understanding of our own stance before our Creator.

[00:44:23] Thank you very much.

[00:44:31] Moderator: [00:44:31] Thank you, Dr. Wilsey. Uh, now we have some time for some questions, so if you could just raise your hand and wait for the microphone, we will get to you.

[00:44:44] Questioner: [00:44:44] Thank you, Professor Wilsey. A wonderful and insightful presentation. Well, as you know, we have a hometown hero here, Arthur Vandenberg. What's the relationship between Foster and Arthur?

[00:44:56]John Wilsey: [00:44:56] Yeah, that's a great question. [00:45:00] So, Senator Vandenberg was something of a mentor to Foster Dulles. In, in 1949, Dulles was tapped by Governor Thomas Dewey to fill out an unfinished Senate seat that was vacated by someone who had gotten sick, and, and this was in the summer of 1949 and there would be a special election held in November for, you know, to finish out the term. And so, so Foster came into the Senate in the summer of 1949, and you know, he didn't have a lot of connections. Well, he had a lot of connections - he had a lot of personal connections, but he didn't really, I guess I should say he didn't really intend on staying in the Senate. Um, but, but he, he had a very close relationship with Senator Vandenberg when he was in the Senate himself. And he was, he came around and he said, I think I'll, I think I'll run for the special election. I think I'd like to, I'd like to be a Senator. Right? And it was largely because of his relationship with Vandenberg.

[00:45:56] He lost in 1949. But, [00:46:00] but Vandenberg and he continued their relationship. Prior to this Vandenberg had helped him get involved in the formation of the United Nations. He invited him to go along with him to San Francisco in 1946 for the very first meetings that, that formed the United Nations. They, they had a very close relationship. They had a very, involved correspondence that the files in the archive of the letters between Dulles and Vandenberg are very thick.

[00:46:31] They were very close friends. They both had a love of nature. They both had loved the outdoors. They, they saw eye to eye on politics. And Dulles is - when Vanderburg died, in 1950 or 51, which one was it? 50? I think it's 50 or 51, it was a loss for Dulles. He lost a friend and, um, he lost an important, a mentor in his life. I think you can also see the loss of Vanderburgh in his life [00:47:00] when he was secretary of state.

[00:47:01] So, yeah. I mean, he has that really important Michigan connection and they were very good friends. Yeah.

[00:47:13] Questioner: [00:47:13] In your research, did you find any evidence of Dulles studying or even reading Abraham Kuyper? I sense a similar characteristic.

[00:47:23]John Wilsey: [00:47:23] That's a great question. I don't see really any evidence that he read Kuyper or any theologian at all. Not just a cursory read. He, he wasn't interested in reading philosophy; he wasn't interested in reading theology at all.

[00:47:42] And when I say that, I mean that's illustrated in his relationship to his son Avery, who became a theologian, and his son, John, who became a historian. When they decided to go into theology and history, Foster was angry with them. You're [00:48:00] wasting your life, you know, he said. You need to be doing something practical!

[00:48:04] So, so Dulles really wasn't very interested in these things, so, so I found no evidence, you know, that he, that he read Kuyper. Although I think you're right, I think that he would resonate with a lot of Kuyper's ideas. Yeah.

[00:48:23] Questioner: [00:48:23] I'm curious what his reaction was when his son became a Catholic priest. The other thing that's interesting, there’s an Acton connection, because Avery Dulles was a mentor to Father Sirico.

[00:48:33]John Wilsey: [00:48:33] Absolutely, yeah. And, and Father Sirico's - when I first met Father Sirico, and he told me the story of his relationship with, with, Cardinal Dulles, and it was really, really fascinating.

[00:48:46] So, yeah, that's a, that's a great question. I developed this pretty extensively in my book. So Avery, when he went to Harvard in [00:49:00] the early forties, and by the time he was a student at Harvard, Avery was sort of a party animal. And he talks about this in his reflections on his conversion. You might've read this. But he was, um, he was tutored by a professor at Harvard who was there on a, on a limited appointment, who was, you know, a deep Catholic theologian, a very conservative Catholic theologian. Avery writes about this; describes him in medieval terms, right? And he really admired this man, and that sort of laid the groundwork for later.

[00:49:38] So in his junior year, Avery writes about being in the library on a cold February day. It was raining outside, it was gross. And he was reading Augustine. And he's decided to get up and to take a little walk, you know, and to get some fresh air. And he walked around and he, for the, he said, for the first time in my life, I noticed the beauty and the intricacy of [00:50:00] God's world around him, right? And he reflected back on what he had learned in his sophomore year from this mentor that he'd had, and he started visiting churches again.

[00:50:09] He hadn't been to church since he was a child. He went to the Presbyterian churches cause he was raised in a Presbyterian home, and they were all, they were all really liberal, right? And he said that, I didn't recognize the God they were talking - I don't... Who is this person they're talking about when they talk about God? I didn't, when I read the Bible, it's totally different from the person they were preaching about. So he decided to go to the Catholic Church, right? And in the Catholic Church, he found the Lord, right? He found the same God in Scripture, he said.

[00:50:38] When he converted to Catholicism. Avery, you know, is a very gracious man. He didn't ever have anything negative to say about any of his family's reactions to it. But, but Foster really struggled with it. Foster, Foster actually took his best [00:51:00] friend at the time aside, his name was Arthur Dean. And Arthur Dean was a, was a, a fellow partner at Sullivan and Cromwell, a New York law firm where he was the managing partner. He said to Arthur Dean, I want you to drop everything you're doing. You need to come to my house right now. The worst thing in my life has happened. Yeah.

[00:51:21] So Arthur and his wife both come and they are, they're both talking to Janet and to Foster about it. Foster had, according to Arthur, Foster had written a letter to Avery disowning him, and he asked Arthur to read the letter and to tell him what he should do. Should I send it? And Arthur said, you don't want to send that letter. You know, a man's faith is a man's faith. And you don't want to coerce your son - this is not worth it. And Foster took his advice, [00:52:00] didn't send the letter. You know, the letter is gone. I don't know. I don't know where it is. He probably destroyed it. And both Janet and Foster, who had at first struggled with the decision of him to convert Catholicism, you know, they, they, it didn't take them long to, to come around. And Avery and Foster carry on a very, very interesting correspondence, especially during Avery's early years as a priest. You know, he's ordained in the 50s, and this is the same time that, that Foster is a secretary of state. They carry on a very interesting correspondence where Avery will write prayers that he is saying on behalf of his father, and his father will respond by thanking him. And he says things like, it gives me a lot of peace knowing that you're praying these prayers for me.

[00:52:50] And so they were, they- I think that Avery and Dulles- and Foster were the closest of the three children. And I think [00:53:00] that the conversion, while it was at first difficult, enhanced their relationship in later years, and that's reflected in the correspondence. So thank you for that. It's a great question.

[00:53:19] Questioner: [00:53:19] Foster - how did he see the United States of America at the time as becoming involved as a world leader, and also did he believe in the United Nations?

[00:53:32]John Wilsey: [00:53:32] Wow. That's a whole other lecture in and of itself. So I'll boil it down, I'll boil it down. In the 1930s and in World War II, through about 1946, definitely 1947, Foster is an internationalist, he is very anti-war. He's not a pacifist, but he is a product of Woodrow Wilson. Woodrow Wilson is one of his most powerful influences, [00:54:00] right? Woodrow Wilson's idealism, Woodrow Wilson's internationalism, really rubbed off on Foster. He was just a young man in 1919 when he went to Versailles. So on the reparations commission from 1919 to 1920, Woodrow Wilson took a very special interest in Foster as a young man, asked him to stay on for several more months in, when his role, his reparations commission- had a lot of faith and confidence in him. And, and Foster looked up to Wilson very much. And, and that admiration lasts a definitely all the way into his negotiating the treaty of peace with Japan in 1950 and '51.

[00:54:42] So he's an internationalist and the mold of, of Wilson, definitely through '46 and '47, but in '46 and '47, with the beginning of the Cold War, and through the end of his life as secretary of state, he still somewhat of an [00:55:00] internationalist, sort of. The way he views international cooperation, though, is in the context of the free world joining together in alliance systems and partnerships for collective security against the Soviets and the communist Chinese.

[00:55:19] And so some historians have looked at this and said he has a radical change. He goes from being an internationalist to being this hardcore religious nationalist, right? And I disagree with that. I developed this disagreement in my book. Foster, it's as though - so for us, as we look back, especially for me, I mean, I'm, I'm 51 years old, so I didn't live through World War II, I was just a baby during Vietnam. So, you know, as his - as we look back on the period of the 1930s and '40s, it's easy - and '50s, it's easy for us to say, okay, we have World War I. We got the depression, we've got World War II. World War II is over in September of [00:56:00] 1945; the cold war starts with, you know, there's a whole bunch of things you could mark the beginning of the cold war: George Kennan's, long telegram, long telegram; you could say the Berlin Airlift. You know, the, all, all of these little markers for the beginning of the Cold War, sometime in between '46 and '48, you know. And the Cold War is different than World War II. This is the way, this is our perspective. This is sort of the way we're all taught about it. This is the way we kind of think about it. But Dulles lived through it all.

[00:56:35] In 1946 he wrote a very lengthy essay for Time magazine, called "Thoughts on Soviet Foreign Policy." And he says in that long article, he says, we cannot let our guard down. It's tempting because we fought this great war. All our, you know, all of our resources gone to the war for the last several [00:57:00] years. We really want to be done with war, but we can't afford to let our guard down with this rising Soviet threat. And the point of all this is to say, Dulles never really stops fighting war between 1945 and 1950; he simply changes in his mind who the adversary is. Whereas the adversary had been Nazi Germany, now that that now the adversary is Soviet communism. But he never stops fighting and, and Americans really didn't stop. They didn't really leave that mindset of being a nation at war. It was just a different manifestation of it, of course, right?

[00:57:42] So I don't think that there's a, there - I think there are changes in the way that he, you know, applies natural law, for example. In his internationalist days, he applied international law to, well, you know, universally to humankind. But in the 50s, particularly from [00:58:00] '50, '51, when he's negotiating the treaty of peace with Japan, because the communists reject natural law, they stand outside of natural law, they're condemned by it. The free world embraces it. So natural law, the moral law really only applies to us and it's opposed to them. And ultimately what will defeat Soviet communism are moral weapons, not physical weapons, which is an idea that Reagan picked up on in his presidency. He talked about that all the time.

[00:58:37] So it's a very interesting, you know, sort of transition that he goes through, but it's a, it's a transition that that is reflected in the times, right? Everybody was going through the same transition, transitioning from seeing the Nazis and seeing expansionist Japan as the enemy - rightly so - to seeing expansionist Soviet totalitarian communism as the enemy, [00:59:00] right? Uh, the war just continues. And you see that dynamic in his life and in the life of Americans in general.

[00:59:10] Moderator: [00:59:10] We have time for one more question.

[00:59:13]Questioner: [00:59:13] As a biographer, can you comment on the current trend of kind of trashing historical figures by viewing them through the lens of political correctness?

[00:59:21]John Wilsey: [00:59:21] Hmm. Yeah. Like so, the only reason I bring Stephen Kinzer in by name is 'cause he's in print. And, when you go in print, you just have to sort of expect that your name is going to be used. And he's all over. He was all over the country when his book called The Brothers, um, how, Allen and John Foster Dulles - Allen and John Foster Dulles and Their Secret World War was the subtitle. He went all over the country and spoke and everything. So all of his ideas are on record.

[00:59:49] And I think that Kinzer is a, is an example of someone who, who, has a very presentist historical framework. When you read his [01:00:00] book, for example, it's like, communism wasn't that bad, you know? We could've lived with it. We could have coexisted. And certainly people in the 70s, Nixon's policy of detante was sort of predicated on coexistence. So, but, but it goes beyond just coexistence, you know. It really wasn't as bad as like the cold warriors said it was.

[01:00:23] And that's, that's, that's a presentist framework. It's looking at, you know, taking our sort of, you know, 21st century mindset and attitude and, and foisting them on these people in the past. And, you know, Dulles, he's sort of an easy target, because yeah, he, he was staid, you know. He was sort of, you know, I mean, for you, he might be described in 2020 as, something like a, uh, you know, a, a, humorless, old white man, you know? And he was [01:01:00] that.

[01:01:01] But just as we are products of our time, he was a product of his time. He was an adult in the room. Nobody knew foreign policy better than he did, just as Eisenhower said when he was secretary of state. Nobody had a better handle on international relations than, than, than Dulles did. He was the exact right man for the job at the time he was there, because his knowledge was so deep, he'd had so much experience. He lived and breathed diplomacy. He was an - all this to say he was a serious adult in the room as a policy maker. And we could definitely use a little bit of that today, not just in politics, but in American culture. It'd be nice to have some adults in the room. Yeah.

[01:01:52] Well thank you very much. Thank you to the Acton Institute. This has been great.

[01:01:57] Thank you, Dr. Wilsey.

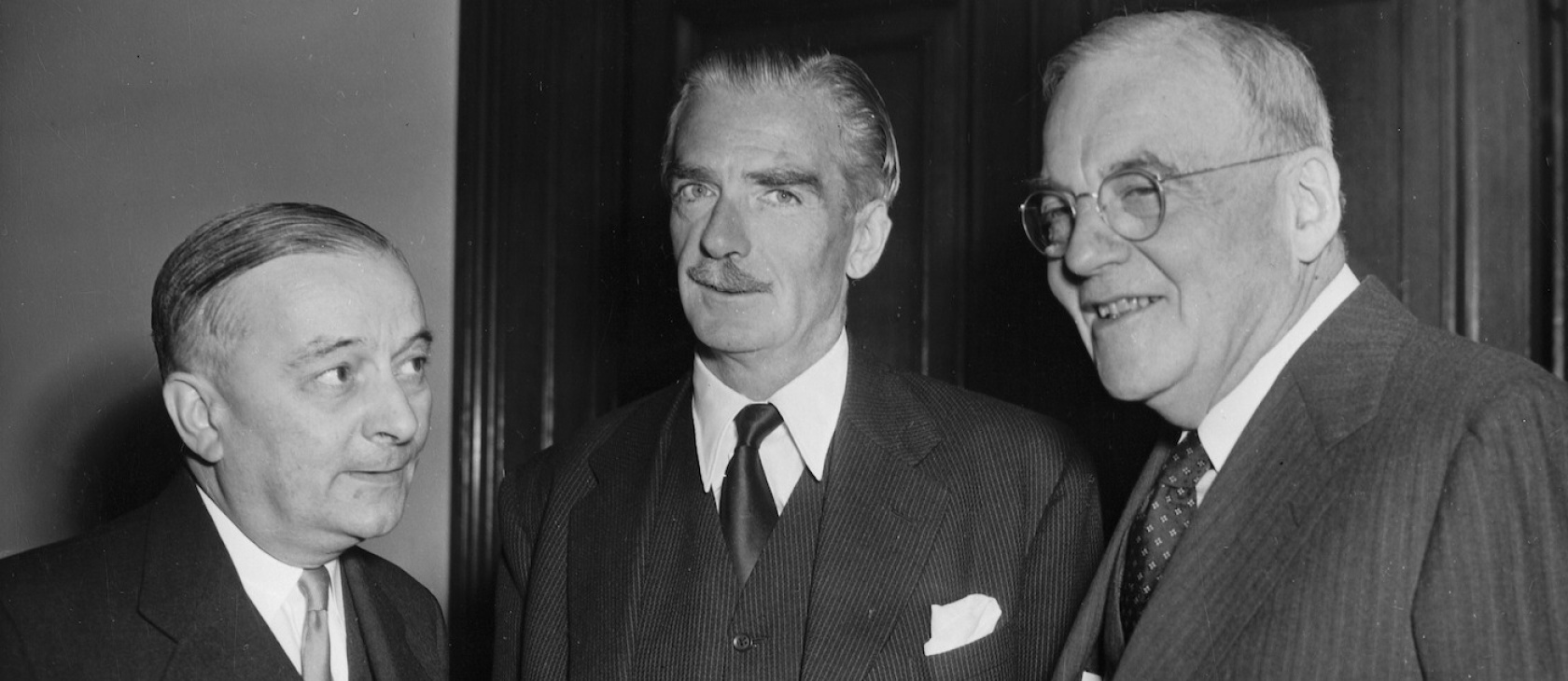

(Photo credit: Dutch National Archives. This photo has been cropped. CC BY-SA 3.0 NL.)