In my introduction to this Romenomics series, I wrote of the diversity of labor and remuneration. It certainly was not a full-technicolor account of business, exchange, and compensation in ancient Rome but, nevertheless, it was a decent overview. Likewise, when addressing “centers of commerce,” that is, where ancient Romans actually did business, I cannot fill in every minute detail, especially because so much physical and written evidence has been lost. Yet I will have as much fun and imagination in providing the extant information as this short blog post allows.

When visiting Rome and what remains of its great imperial cities, one fact stands out: Vital hubs of commerce were built around a few dozen hectares of rectangular land called fora (from fores, meaning “outside”). In effect, rain or shine, from sunrise to sunset, fora were always ready to host commercial activity in these large outdoor spaces. They provided outlets for both spontaneous and ordered exchange, not too different from American flea markets, Italian mercatini, or Turkish bazaars. In concept and design, Roman fora eventually became ever-more architecturally complex, incorporating permanent buildings, just like Europe’s famous broad plazas with integrated shops, bars, restaurants, commercial offices, temples, and even town halls.

When visiting the ruins of the Forum Romanum, tourists are often bewildered and even disappointed. They find piles of rubble, stone columns like fallen logs in a forest, walls that looked carpet-bombed by air-raids, and just a lot of “junk” everywhere to trip over. What often remains are not commercial structures but religious and political venues (temples converted into Christian churches and the Roman Curia). It takes a wild imagination and patience in the searing Roman heat to contemplate what went on during a bustling business day. Even more difficult is to envisage where exactly it was conducted in the forum before it was completely ransacked and destroyed by bands of raiders and barbarians throughout the fifth century.

First things first: While the Forum Romanum started out as a relatively small, open market from converted swampland during the early Republican period, by the time of Julius Caesar it would be considered the “downtown.” It was the place “to be seen,” where major deals were made with gods and men. The main portion grew to become 250x170 meters (practically two football fields) and with later add-ons by Augustus and Trajan. The Forum Romanum grew to become absolutely congested with sophisticated brick and marble structures: 10 major temples; three massive basilicae (used as spaces for formal negotiations, legal consultation, and cover during bad weather); the convent for the vestal virgins (whose job was to conserve the perpetual sacred fire that protected Rome); the Curia (Roman Senate); the Rostra (a raised colonnaded platform used for promulgations and political speeches); a prison for the most dangerous criminals; and little open space for day-to-day shopping, banking, and exchanging goods and services. The Forum Romanum ended up being more an elite point of assembly for religious, civic, and political actors rather than its original purpose of facilitating enterprise.

So, where did all the real business take place in the city of Rome? The short answer is in many other much smaller specialized fora scattered around the city center, along the banks of the Tiber River and the periphery. There were dozens of open markets which have left virtually no archeological trace, but we do know their names. In brief, the main fora minores were for butchered meat (Forum Macellum); fresh fish (Forum Piscarium); pigs and salted pork (Forum Suarium); cattle, leather, milk (Forum Boarium); goats and cheese (Forum Caprarium); sheep, wool, and textiles (Forum Lanarium); olive oil, fruits, and vegetables (Forum Holitorium); wine (Forum Vinarium); bread, flour, and cereals (Forum Pistorium); housewares, statues, and vases (Forum Archemonium); and spices, delicacies, and luxury goods (Forum Cupedinis).

Later, attempts were made to consolidate the many smaller, specialty markets into what we might call “one-stop shopping centers” like the completely destroyed Macellum Magnum built by Nero on the Caelian Hill, and the first-ever “indoor mall”: the Mercatus Traiani, which is still standing on the Quirinal Hill. This five-story building housed dozens of shops (tabernae) that mostly sold luxury goods but also everyday items. Like today’s malls, Trajan’s Market also focused on selling hospitality and entertainment: there were several bars in the attached Via Biberatica (“the drinking alley”), terraced restaurants on the second floor with views over the Forum Romanum, and theater (outdoor) for drama and music festivals. It has had high-end office space for legal and commercial entities. Its shops are still perfectly intact today, so one can get a clear idea of the physical space that Emperor Trajan rented out to entrepreneurs and luxury traders from all over the empire.

One simple structure whicb was a fixture of all tabernae and outdoor stands, particularly at money-exchange kiosks, was the bancus. The bancus - essentially wooden planks tied together to be easily dismantled at the end of each business day - served as a wide countertop at which transactions were conducted and where money tills were kept to collect payments. No wooden bancus has survived natural decay, but linguistically they still survive in the word “bank,” the precious institutions we still require for making transactions possible!

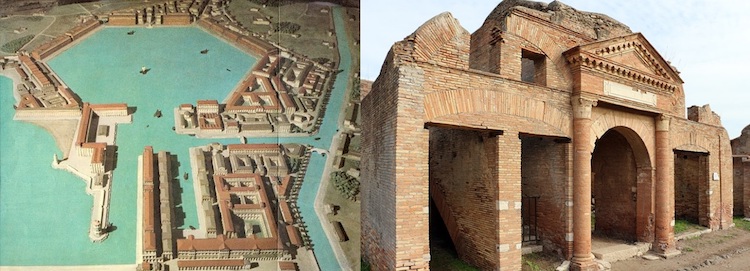

Enough said about commercial life in the city centers. What about the seaports? Since Rome’s ancient port – Ostia – has been fully excavated, we have many visible clues. First, if the large cities were dedicated to trading, the port cities were commercial centers par excellence. When visiting Ostia today, several square miles are dotted with small and large tabernae, together with all the above-mentioned fora for imported delicacies, raw materials, grains, and, of course, seafood. Restaurants and bars were numerous and often specialized in recipes made from luxury foodstuffs and drink from abroad.

Port cities, like Ostia, were often built along shallow coasts that had naturally calm waters and bays, or along river estuaries so as to connect to inland shipping waterways. Most importantly, port cities had special facilities called horrea to warehouse tons of merchandise until it could be transported, redistributed, and sold in other markets. Typically, horrea were designed to store grain, salt, and building materials such as marble and granite. Luxury items - such as precious metals, gems, and spices - were not kept here but in smaller guarded tabernae with locked rooms.

Warehousing becomes such an important part of the commercial port infrastructure that Romans built secondary man-made harbors with attached docks and huge horrea. In 46 A.D., Emperor Claudius commissioned the supplementary town of Portus (where we get the name “port”), a few miles north of Ostia, to relieve the high volume of imports it received every day. Emperor Trajan later expanded Portus and modified its dock structure into a hexagon for enabling six separate docking sites that operated night and day. Portus was then connected to Ostia's Tiber docks via a canal for inland delivery.

While we have spoken about cities and port towns, Roman centers of commerce were for the most part agrarian - gigantic estates used for farming, raising livestock, logging, mining, etc. Plebeians could purchase small private plots (a few hectares), and retired military received small fertile lands; however, the large commercial agrarian operations (hundreds and thousands of hectares) were owned by the patrician aristocrats and senators. They focused on industries that had large profits and demand, such as viticulture, cereal production, raising cattle, logging, and quarries. Their lands were frequently adjacent to waterways for cheap and immediate shipping. The latter factor was especially necessary to avoid spoiling of farmed goods and to urgently service large-scale imperial projects (construction, road building, smelting for arms, and military gear).

What can we learn about ancient commercial centers that still applies today? Firstly, we need both primary and secondary centers of business and distribution. No one metropolis can have a single center. The great Forum Romanus tried that; then, due to overcrowding, it had to splinter into specialized markets dotted throughout the city. This relieved traffic congestion and allowed for much larger volumes of trade and competition for the individual sectors. As cities grow and become more and more spread out, the splintering of market centers eventually creates a new logistical problem of distance. (Imagine walking – the blisters! – and hauling carts several miles between separate meat, oil, and vegetable markets in ancient Rome.) Eventually, the convenience of the Forum Romanus is found in a middle-ground solution via malls and shopping centers, such as Trajan’s Markets and the Marcellum Magnum. In fact, this is the most enduring Roman model of commercial real estate in today’s big cities. The same is true for the use of seaports, where primary and secondary centers must be built to work in harmony with each other and with interconnecting logistical routes.

If there is anything we admire about the ancient Romans, it is their constant cognizance of efficiency. They would continually rethink, restructure, and redistribute to make a vast empire commercially serviceable more quickly. In business, then and now, tempus pecunia est ("time is money"). Rome’s ancient business centers were well equipped to maximize this eternal maxim.