This is the third installment of the "Romenomics” series, which aims to study commerce in ancient Rome in order to better appreciate the economic present. See part one and part two of the series. - Ed.

In the last two Romenomics essays, we reflected on human labor and where commercial exchange took place in ancient Rome. This was not simple, as so many official records and venues have been lost or destroyed. We needed to use some imagination. Now, identifying the major sectors of Caput Mundi’s economy is a far easier task, though descending into particulars, such as gross production, will require some “guesswork” and extra research.

In summary, agriculture always was the largest economic sector in ancient Rome. In its rural context, major sectors also included mining, lumber, and livestock. Other massive slices of the economic pie included the military and related support industries. Of course, there was what we now call retail (shops, stands, and open markets discussed in the previous blog) and the transportation sector (shipping, carts, pack animals, roads) that brought goods to market from near and far. No economy, including that of ancient Rome, can function without a financial sector – from banking, minting, payment collection, and currency exchange. Finally, Rome wouldn’t be Rome without its magnificent art, architecture, and related public works such as temples, stadiums, amphitheaters, baths, et al., that supported its religious, entertainment, leisure, and sports sectors.

Think about it: How could emperors promise to dole out millions of loaves of bread for their popular panem et circenses without counting on massive grain deliveries coming to Rome on a daily basis? A wide variety of cereals were produced exclusively to be given away as cartloads of bread at circus games. Bread was the food staple for the ancients, much like pasta is for modern Romans. In addition, cereals were used to cook daily hot porridge (puls); dried, crumbled, and mixed with soups; and used in various pastries. Around 70-80% of Rome’s daily caloric intake involved some kind of grain.

It was impossible to calculate exactly how many tons of grain were produced, shipped, and distributed annually in ancient Rome. Yet as the UNRV history website rightly notes, Rome wouldn’t have grown without it:

The need to secure grain providing provinces was one of many important factors that would lead to the expansion and conquests of the Roman State. Among these conquests were the provinces of Egypt, Sicily and Tunisia in North Africa.

As was noted in part two, Ostia and other Roman seaports were packed with horrea – massive brick-structure storage facilities – as holding and distribution centers. They were ready to receive hundreds of tons of grains that could arrive on cargo vessels at any given hour. Grain was never stored for long periods for fear of mold outbreak or rodent invasion.

If cereals made up the lion's share of the Roman diet, the second most valuable agricultural product was olive oil (10%). A variety of vegetables, herbs, nuts, and fruits made up the remainder – including fruit drinks, like the omnipresent vinum that was frequently diluted with water and sweetened with honey. Just like today, typical Roman crops included wheat, barley, artichokes, onions, celery, basil, rosemary, asparagus, fennel, capers, cabbages, garlic, figs, apricots, plums, peaches, and grapes of infinite varieties, some of which have been preserved through the centuries - like vinum moscatum (Muscat dessert wine) and vinum caesanum (Cesanese red, now all the rage in Rome and competing with world-renowned Chianti wines from Tuscany).

Agriculture was so fundamental that a good-sized family living in rural conditions (with no nearby trading centers like fora) needed roughly 20 iugera (about six hectares) of farmland to be self-sufficient. A third of their land’s production was often paid as rent to wealthy patricians, if it was not directly owned by plebeian farmers.

It must be further noted that meat, poultry, and fish were expensive, and most Romans did not eat vast amounts, so this was not a huge sector. It was limited more for consumption in restaurants and on special occasions.

Finally, part of the rural economy was tied to other natural resources. Here we are primarily referring to lumber and mining, especially iron, copper, silver, gold, and tin. Lumber was used, just like today, in homes (roofing beams) and for furniture (beds, desks, chairs, countertops) but unlike today for transport (cargo vessels, warships, carriages, carts). Good, hard wood was the “steel” of ancient Rome and was in such high demand that entire oak and chestnut forests were stripped in rural Rome, leading to massive floods and mudslides. Roman mining also inflicted similar abuses of the land, as Romans used hydraulic mining technology to strip topsoil (ground sluicing) and find shallow veins and deposits. The technique literally ruined entire mountainsides in exchange for massive production:

Hydraulic mining, which Pliny referred to as ruina montium ("ruin of the mountains"), allowed base and precious metals to be extracted on a proto-industrial scale. The total annual iron output was estimated at 82,500 tons.

Ground sluicing allowed Romans to scale mining to proto-industrial levels, which were “not matched until the Industrial Revolution” while extracting most of what was once richly available in Spain (gold, silver, tin, lead), France (gold and silver), Turkey (gold, silver, tin), the Danube regions (gold and silver), and Great Britain (coal and iron). Iron and lead production reached incredible levels of production at more than 80,000 tons annually.

Granite and marble quarries played their own part in the ruina montium, slicing through entire hillsides to meet colossal demands for civic buildings such as temples, stadiums, amphitheaters, and the decorative art sector. Wooden cargo ships were often hazardously overfilled and capsized in mildly choppy waters. The same fate met ships containing iron ore and lead being shipped to smelters working day and night to meet demands for constant orders of military equipment and weaponry. The vast majority of precious metals, like silver and gold, were more carefully transported in smaller vessels and accompanied by guards to imperial mints.

Money matters in ancient Rome were not so different from today, though the methods of management, collection, and credit were dissimilar. There were banks (which held deposits and made loans), state treasuries, and tax collection systems. There were mints and currency exchanges. There was also a form of corporate finance.

Money wasn’t easy to lend. Loans were initially given in small amounts and essentially under oral “gentlemen’s agreements." In these cases, one’s reputation was essentially the collateral for any minor lending. Later, as credit included larger sums of money, written agreements developed. Contracts on papyrus were made in duplicate, with one going to the loan recipient and the second sealed between wax tablets for preserving the chirographum, an IOU record. (Today, we might make a scan or a PDF copy.) In the chirographum, the collateral would be clearly stipulated (a home, a plot of land, livestock, even slaves).

For large-scale business loans, wealthy patrician families would act outside the banks by pooling their finances, creating a societas - that is, a small company or corporation. Today, the Italians and French still use the same word (società, société), but there was no such thing as a publicly listed company.

Secondly, private money deposits were not kept in “banks” but in temples. (A bancus, from which we get the word “bank,” was a wooden table used by money-changers.) Needless to say, a money-exchanger’s bancus was never too far from a temple, sometimes on the steps or porch – a bad cultural habit that often violated pious respect of the religious use of temples, as was noted when Jesus angrily overturned the money-exchangers' tables outside the Jewish Temple.

Deposits were kept in temple basements and guarded by military and private security. Since temples maintained sacred fires, the temples were at risk of burning down. So, bankers diversified their risk by spreading out their deposits across several different temples, a strategy not too different from having several “bank branches.” State treasuries and mints also made use of temples to keep money safe, which gives another meaning to the phrase the U.S. Treasury prints on Federal Reserve notes: “In God we trust.”

In the city of Rome, the Temple of Saturn was the main treasury, or aerarium, whose columns are still visible a few meters from the curia (Senate building) in the Forum. Both Senate and treasury officials (quaestores) supervised public funds accounted for at nearby tabularium, where taxes (tributa) were sent after being collected by privately contracted (and hated) publicani. There tributa were counted and earmarked for projects. The Temple of June Moneta on the Capitoline Hill above the Roman Forum served as the mint, the site of which is now St. Mary Altar of Heaven (Ara Coeli) church and would have been the Fort Knox of its day.

When we first visualize Rome in our minds, we naturally imagine the remains of some of the greatest public works that were miracles of civil engineering, like the Pantheon and the Colosseum. It was estimated that during Rome’s Golden Age, one-third of the Roman economy revolved around public building projects for infrastructure (aqueducts, wells, sewers), logistics (ports, roads, bridges), entertainment (amphitheaters, stadiums, arenas), religion (temples, votive altars, statues), hygiene and health (baths, gymnasiums) government buildings (curia, treasuries, accounting offices), and shopping (markets and malls).

Rome’s greatest public works legacy is its road system (much of which is still in use today). Roman roads made for relatively fast, safe, and efficient distribution of commerce. To summarize the “Roman roadmap,” which required thousands of laborers and billions of tons of paving stones:

29 military highways radiated from the capital … and the Empire's 113 provinces were interconnected by 372 great roads. The whole [network] comprised more than 400,000 kilometers (250,000 miles) of roads, of which over 80,500 kilometers (50,000 miles) were stone-paved … Many Roman roads survived for millennia; some are overlaid by modern roads.

Hadrian and Trajan were the leaders of expanding Rome’s superstructure. The empire had built more than 230 amphitheaters that seated at least 7,000 people, hundreds of gladiatorial arenas, circuses for chariot racing with capacities of 50,000 to 250,000. The city of Rome had 11 aqueducts that extended for 260 miles, delivering fresh water daily to 1 million residents. The old saying, “Rome wasn’t built in a day,” refers to the years (even decades) these massive public works took to complete. For example, the Colosseum took 10 years, the Pantheon 12 years, the Baths of Diocletian eight years, and the Forum Romanum was expanded over several hundred years, as were the Roman roads. (It was always “construction” season in Rome.)

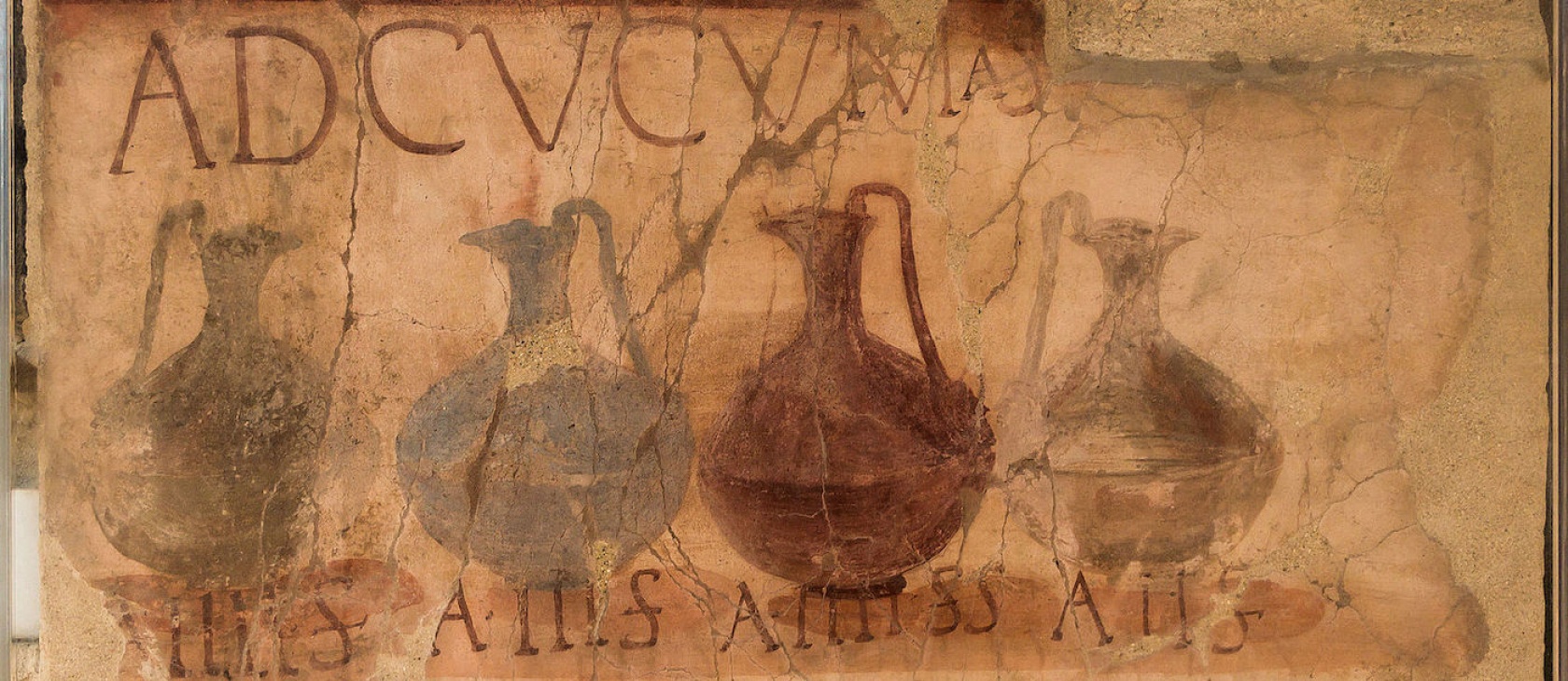

Finally, Romans spared no expense (nor material) in the art sector. Italy’s museums are overflowing with Roman art of every variety. They used bronze, silver, gold, terra cotta, ivory, lead, wood, marble, common stone, and gems. They made statuary, mosaics, sarcophagus tombs, jewelry, frescoes, reliefs, triumphal arches, and columns. Nothing was exempt from artistic creation - even a massive bath carved out of the rarest Egyptian porphyry marble (worth platinum in its day) for Nero's Golden House. It is now prominently displayed in the Vatican Museums, along with the original, lavish mosaic floor.

When it came to the world of art, the phrase “veni, vidi, vinci” could be metaphorically applied, as the Romans admired, conquered, and expanded Hellenistic, Etruscan, and Middle Eastern art traditions and scaled them commercially. The patricians and emperors were noted “consumers” of art, spending the equivalent of billions of dollars a year to adorn their villas, public buildings, and mausoleums with artistic masterpieces.

What we learn from major Roman commercial sectors is that bigger was better - and not just better, but truly necessary to service a giant empire with a never-ending appetite for building and expansion. Rome did not just have to think "big" but also quickly and efficiently to meet the needs of industries which often consumed faster than they could produce. This still holds true today for global industry.

We would never see the above-mentioned sectors “scaled” to such levels until the first Industrial Revolution, when empire-building became all the rage again in early modern Europe. The British, French, Spanish, and Portuguese all looked abroad for resources in the Americas, Asia, and Africa, particularly to replenish those natural materials that were dwindling in their home nations; ironically, these were often the very same resources already plundered by some ancient empire.

Where the Romans failed was not so much scaling their industries but making them sustainable and respectful of nature, a challenge we still face today. Then and now, we must avoid ruina montium, as Pliny noted, while at the same time seeking new summits of industrial prosperity.