Devotees of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America will be more aware than most of the debt the United States owes the Puritans. While his account is impressionistic rather than historical, it captures the essential truth that Puritan notions concerning political participation, limited government, and the importance of natural and divine law shaped the nation in a variety of ways.

The Puritans refused to be complacent in the face of threats to their liberty—especially the freedom of the church.

Yet Puritan views of government and the qualifications for godly rulers were largely of a piece with the rest of Christian political theology: All authority, rightly understood, was derived from God, and all rulers, from the king to the town selectmen, were merely His agents, responsible for the welfare of those they governed. Divine law as shown in both nature and revelation was seen as the animating force for positive law, as it not only marked the standards to which positive law ought to accord but also set limits to those things over which the state may legitimately exert its authority. Divine law was the principal source of human liberty, even as it served as the boundary keeper, preventing liberty from devolving into license.

None of this is exclusively Puritan—in the English tradition, John of Salisbury espoused similar views, even up to and including positing the legitimacy of tyrannicide. Nor would the Puritans have claimed to be offering up innovative political ideas; in politics, as in so much else, their own sense was that they were recovering an ancient biblical understanding, one reflected in the tradition of English common law.

Nevertheless, in their own time and in ours, Puritan views of government are worth studying precisely because they strove rigorously to apply biblical principles without the intermediary of tradition. In the English colonial settlements of the 17th century, Puritan thinkers were able to put their ideas into practice, testing the notion of a “godly commonwealth” grounded on a robust understanding of human equality and liberty.

Convinced that Christ’s church must be comprised only of the elect (and not, for example, of everyone who happened to live within the geographical bounds of the parish), English Puritans often adopted the biblical notion of covenanting, the forming of communities bound by ties of mutuality to one another and to God. While the Puritans acknowledged that men might fall into different ranks by the will of God, they did not imagine those to mitigate against the essential equality of men in status as created beings, image-bearers. The Puritans reasoned that human governments in both church and state derived their authority from the consent of the people. In this they were influenced by work in biblical interpretation that emerged in Europe in the 16th century providing a reading of the Old Testament that emphasized the republican elements of Israel’s government before they asked God to give them a king “like all the other nations.” This “Hebraic republicanism” showed God’s original intention to work mediately through consensual, limited types of governments, and stood in stark opposition to theories of divine-right monarchy.

This approach to private associational life logically spilled from religious to civil societies in the context of New England, where the colonists regularly described themselves as “combining together” to create political societies on both the town and colony level. In 1630, John Winthrop wrote in his “Model of Christian Charity” that the goal of such communities was a radical unity: “For this end, we must be knit together, in this work, as one man. We must entertain each other in brotherly affection. … So shall we keep the unity of the spirit in the bond of peace.”

Unity and peace were lofty goals for those stalwart souls who were fleeing England’s shores precisely because of their inability to refrain from dissent in their native land. Covenantal associations were voluntary, and the fractious nature of Puritanism meant that new towns and churches were often started because of an unresolved disagreement among the members of some older covenant. Yet for as long as an individual chose to remain in a particular community, his obligation to “walk” with his neighbors peaceably was also an opportunity—really, an obligation—to participate in shaping the local understanding of what such a walk ought to look like. Town meetings were places for discussion and debate, and historians have long recognized that participation in such meetings was customarily open to all residents of a community and not merely those who met the formal qualifications for freemanship and the suffrage privileges that went along with it.

The Puritans understood their political covenant to be more than just a bond between individual citizens, but rather between their community as a whole and God. This led them to a radically different view of the bond between citizens and their representatives.

In the 1645 “Little Speech on Liberty,” Winthrop argued that the relationship between magistrates and people was akin to that of a married couple. Taking his cue from Ephesians 5:21–24, he wrote: “The woman’s own choice makes ... a man her husband; yet being so chosen, he is her lord, and she is to be subject to him, yet in a way of liberty, not of bondage.” As the husband was the ultimate head of the household, so too the magistrates were (for the duration of their election) the ultimate head of the commonwealth. Just as the wife would, one hopes, be regularly consulted in her husband’s decision-making, so too Massachusetts’ magistrates both expected and invited public consultation. Not only did the Laws and Liberties—Massachusetts’ law code/constitution, whose history stretched back to the 1630s—explicitly protect the rights of “every man whether Inhabitant or Foreigner, Free or not Free” to participate “either by speech or writing” in all levels of civic government “to present any necessary motion, complaint, petition, bill or information,” but the magistrates frequently requested the local town meetings to weigh in on questions facing the colony. It was not a perfect system, by any means, but the historical record indicates a robust level of participation.

This view of the magistrate as head of the civic household had other implications. John Winthrop’s journal provides insights into the problem of those who neglected their obligation to the broader community, recording examples of individuals chosen to serve in positions of civic responsibility who attempted to resign mid-term. These attempts were always met with concern and generally disallowed in much the same way they would frown upon a divorce without biblical cause. To resign was to be guilty of “forsaking [one’s] calling,” as well as a breach of promise to serve the community. After one such incident, Winthrop reports that it was the unanimous opinion of the Massachusetts Bay leadership that a magistrate “could not leave his place, except by the same power which put him in,” an attitude toward representative government that to some extent privileges the act of election (and the will of the electors in that moment) over the independent agency of the elected official who becomes the servant of the public. Then, too, it also suggests a moral if not legal responsibility of the voting public to be responsive to the changing attitudes of their representatives, and to be willing to free them from their public duties should they become overly burdensome.

Thus, the Puritan as governor must be understood to value consent not merely as a formality (i.e., in the act of elections) but as the ongoing dialogue between rulers and ruled, and thus a means of building genuine unity among the disparate members of a body politic. The Puritans faced a tremendous challenge, however, in the degree of unity their covenant required to function well.

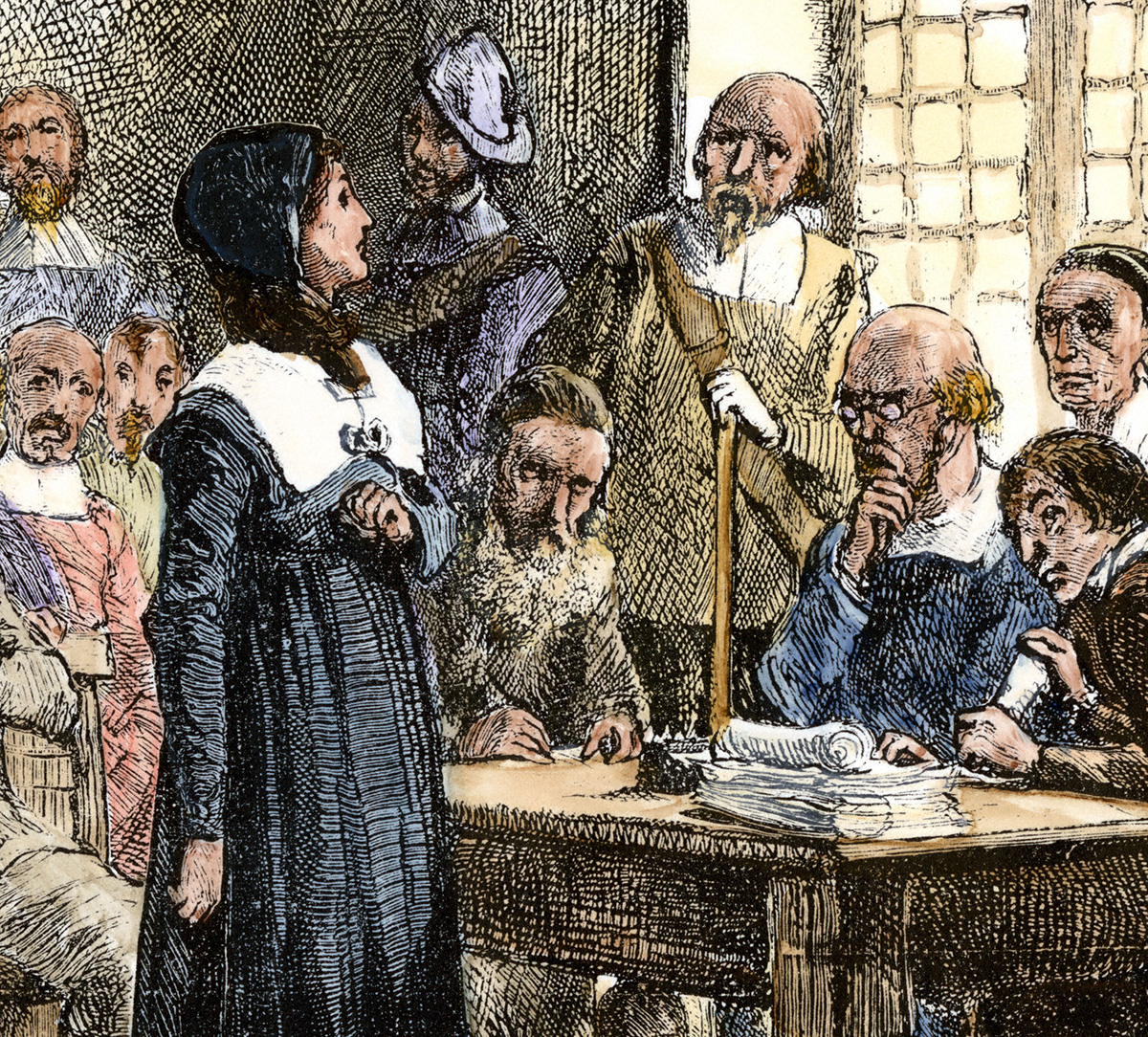

If you ask most Americans what they know about the Puritans, chances are the response you get will have something to do with either witch trials (thank you, Arthur Miller) or their alleged hypocrisy in suppressing minority religious views. If the person you are speaking with is very well informed, they may name Anne Hutchinson when making the latter charge. Hutchinson’s “antinomian” (literally, anti-law) views went against the teaching of the majority of Massachusetts’ clergy that the Bible urged believers to observe morality and orderly behavior as guardrails against personal sin and public chaos.

Often portrayed as a proto-feminist boldly facing down the patriarchy, in fact Hutchinson threatened not just the governing authorities but the very roots of Protestantism. Her assertion that God’s spirit spoke to her “by an immediate revelation” in a clear and incontrovertible way, and her refusal to acknowledge any other authority, went well beyond the pale of mainstream Protestantism and threatened the carefully cultivated sense of public unity that the magistrates valued so highly. Yet in dealing with Hutchinson (and with many others whose names are long forgotten), the General Court—which served as both legislative and judiciary for Massachusetts Bay—was far from hasty, offering multiple opportunities over the span of several years for her to either persuade them of the legitimacy of her position or to recant, despite their severe concerns that those who were saved were absolved from the strictures of divine law and could live by grace alone.

While the goal of the magistrates was to foster a deep sense of unity among the people, they were not to pursue uniformity for uniformity’s sake. The Puritans recognized that there was room for reasonable persons to disagree about even relatively major questions of religious doctrine or public policy and preferred to use the art of godly conversation, as well as the power of the press and pulpit, to change hearts and minds rather than simply to coerce conformity. In dealing with dissenters, as one commentator observed, the ideal was to use “convincing light for the means and compassionate love for the manner” and “till this course prevail … forbearance may be exercised to all sober people so it not be against piety or peace.” Although Massachusetts’ Laws and Liberties provided for the protection of conscience claims, these were restricted to those “orthodox in judgement and not scandalous in life”—a judgment, of course, that lay with the magistrates. Those whose beliefs were considered unorthodox in ways that specifically threatened the colony’s stability found themselves invited to make their homes elsewhere. As foreign as this is to the modern mind, the ability to restrict membership in one’s civil community to those who shared a particular set of fundamental views was not in and of itself controversial in the period. Puritanism as a political project doesn’t make any sense if the community cannot, in fact, take measures to ensure its purity.

Consider the logic: When a civil society is formed by consent around a set of shared principles or beliefs, it is obviously the duty of those charged with governing that society to see that those principles are maintained. This might well require hard or unpleasant work. In a sermon preached in 1667, for example, Jonathan Mitchell wrote: “To [seek] a people’s welfare is to put forth utmost and best endeavors to procure, promote, and maintain it; to study it and to speak for it; to act for it, as occasion is. It is not an empty wishing and woulding … but to do.” Likewise, John Oxenbridge chided those standing for election in 1671: “If ye shall break down the hedge of your churches and commonwealth, you will lay the field open to such as want to make spoil of you. … If you admit of a carnal party into the privileges due here to visible saints, they will be likely to eat out the heart of liberty and religion.” Just as the ministers of Christ’s church were to guard its purity, ensuring that only those who were truly faithful were admitted to communion, so it was the magistrates’ duty to guard the commonwealth, ensuring that only those who were willing to abide by the covenant remained within its fold.

This watchfulness was for the good of all. Thomas Shepard, an esteemed Puritan minister who consulted regularly with members of the General Court, pointed to 1 Timothy 2:2 to assert that the divinely appointed ends for government are “that we may lead a quiet and a peaceable life, in all godliness, and honesty.” Yet the magistrates were not to rely upon their own judgement but on the standards set by the community at large. “Where laws rule, men do not,” Shepard observed, presuming the laws to have been framed with the input of the community as a whole and therefore framed in such a way as to interfere minimally with the liberties of the people.

With their public commitments enshrined in just and well-framed laws, the people themselves provided orderly boundaries to both the exercise of individual liberty and arbitrary state power. Pride, in particular, was a woeful concern to the Puritan magistrate, for it led to the sort of “chronic distemper” of spirit that made men “in their own apprehension good enough to rule and too good to obey.” The magistrates were expected, therefore, to take measures to encourage virtue and discourage vice by passing appropriate legislation. Although it was not possible for laws to address the inner vices that resulted in outward sins, it was nevertheless incumbent on the magistrates to do what they could to encourage “outward Reformation.” The Puritans made much of the distinction between inward and outward government; whatever the true state of his heart, the man who was able to govern his own passions, restraining his tendencies towards sin and cultivating outward virtue, would require less direct rule by others.

Thus, private virtue served as a hedge against public corruption, abuses of power, and even tyranny. Were the people to find themselves with rulers who used civil power to further their own ends, rather than the good of the commonwealth, the people had a right to remonstrance, for, as John Davenport reasoned, “the power of government is originally in the people.” Because men were “reasonable creatures,” Davenport went on to explain that it was necessarily understood that the powers of civil government were limited in both their extent and duration. There were “set bounds and banks to the exercise of that power, so as it may not be exuberant, above the laws and due rights and liberties of the people,” and were it to become detrimental to them, the people might reclaim the power from those they had deputized to wield it.

In dire cases, where ordinary elections were not sufficient to remove the offending magistrate, the Puritans were notable for their willingness to articulate a doctrine of active resistance. In his 1644 book The Keys of the Kingdom of Heaven, John Cotton noted that where the higher powers were acting unjustly, it was the task of lesser magistrates to work together to ensure the “preservation and protection of the laws and liberties” of the people. In Massachusetts, this often took the form of colonial leaders resisting the incursion of royal authority.

Pride led to the sort of ‘chronic distemper’ of spirit that made men ‘in their own apprehension good enough to rule and too good to obey.’

After the Stuart Restoration of 1660, for example, petition after petition came into the General Court from the towns and clerical advisers urging the colony’s leaders to resist the king’s efforts against their charter privileges. Reasoning that their civil liberties were the gift of God and essential to sustaining their political existence, one group of ministers counseled the colonial government that it was incumbent upon them to resist because “men may not destroy their political any more than their natural lives” without guilt.

Thus, the General Court initiated a decades-long struggle with the king. When they did eventually take up arms against the king’s representative in the colony, they were careful to clarify that this action had been done in an orderly and God-fearing way. Using the biblical reasoning that inspired so much of 17th century Anglophone colonization, the authors went on to say, “We have been quiet hitherto; and so still we should have been, had not the Great God at this time laid us under a double engagement to do something for our security.” This “double engagement” was a fear for their very survival under Royal Governor Edmund Andros’ maladministration, as well as the news of the actions of other “lesser magistrates” in England in overthrowing James II. As Cotton Mather would describe it, the Boston Revolution of 1689 was both “just and fair,” for the pious men involved were “not resisting an ordinance of God but restraining a cursed violation of his ordinance” that, in fact, favored individual liberty. This reasoning would prove equally fruitful to the leaders of a later colonial rebellion in the century to come.

The United States is home to many experiments in religious association, but none was more influential than the one the Puritans established on our shores. Although the Puritans’ desire for a covenant community bound by the Reformed faith is unlikely to be replicated, their clarity about what is required for maintaining unity and protecting against tyranny stands as an important reminder. The Puritans knew that a refusal to respect the boundaries of a political community is the surest path to its demise and took strong measures to maintain peace and affection among their citizens. Such clarity on these matters is in short supply today. While many in the West would find the substance of their commitments impossible to follow, they nonetheless show the importance of erecting hedges around a community’s core commitments. That so few are even willing to countenance this today shows our loss of seriousness.

Even as they remain an imperfect model of how to deal with internal threats, the Puritan vigilance against abuses from above stands as a lesson to us today. Here, too, we could learn much from their example, both in terms of the restraint the Puritans showed by patiently petitioning first and only later pursuing rebellion through the lesser magistrates, and in their refusal to stand by and do nothing when their unique political identity was threatened by those charged to protect it. The Puritans refused to be complacent in the face of threats to their liberty, especially the freedom of the church, and this in particular should inspire Christians of all kinds to renew their own defense of the faith in public life.