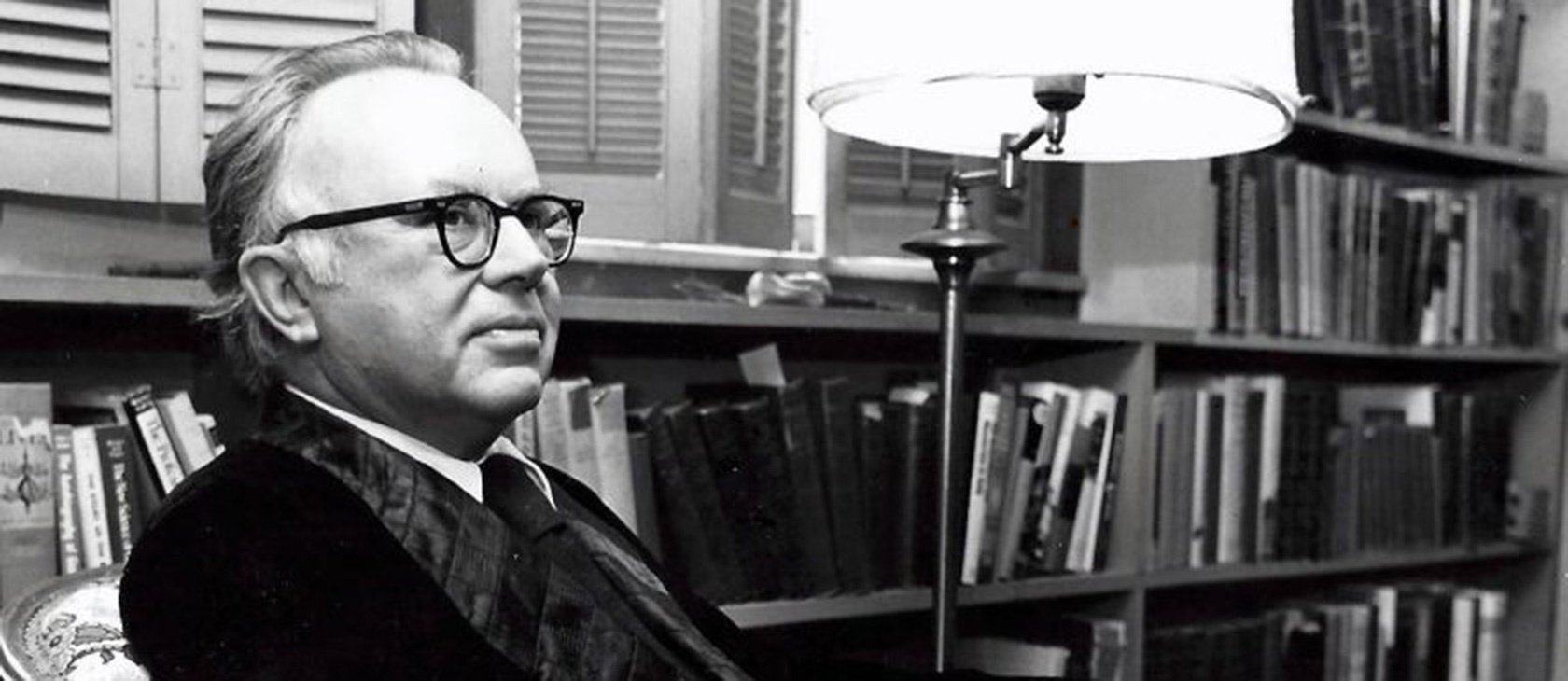

This year, we celebrate the centenary of the birth of Russell Kirk, a member of the Acton Institute’s Board of Advisors from its founding until his death in 1994. His astute analyses ranged from his doctoral thesis – which became The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Santayana (later editions were expanded to include T.S. Eliot) – to an economics primer, ghostly fiction, literary and political biographies, and much, much more; all worth reading.

Eventually, Kris Mauren and I had the good fortune of meeting one of the twentieth century’s great minds as we set out to assemble the Acton Institute’s Board of Advisors. I cannot recall the first time I met Russell or even the location, but I do remember I was quite familiar with his landmark magnum opus, The Conservative Mind, as well as his byline in National Review and elsewhere. Before too long, Russell’s daughter became Acton’s first receptionist, and I became a semi-regular guest at his ancestral home, Piety Hill, and his library, both of which are located in the mid-Michigan village of Mecosta. Russell and his bride, Annette, were also frequent guests at Acton events. In fact, his very last speech was given at Acton in 1994.

I didn’t always agree with Kirk – I still maintain his essay “The Chirping Sectaries” erroneously gives short shrift to libertarians, and his last speech wasn’t exactly a hagiography of our institute’s namesake, Lord Acton. But only the most callow of individuals would allow such minor cavils to stand in the way of fully appreciating Kirk’s massive body of work. (Some of his previously unpublished observations are still working their way into print, as attested by the release this year of a major volume of his correspondence with friends, family, and fellow luminaries.)

We certainly appreciated our access to Russell and easily found common ground. Specifically, his textbook, Economics: Work and Prosperity, wonderfully encapsulates the free-market ideals the Acton Institute espouses. In this 1989 work, Kirk shows himself adept at explaining the basic principles of economics by employing biblical passages from both the Old and New Testaments, as well as fables, poetry, and philosophy. It’s a magnificent work that I highly recommend for those seeking to instruct young people in the basics of economics, as well as those adults interested in a remedial education in the “dismal science.” For example, he wisely notes, “It is better to be relatively poor in an efficient economy than to be absolutely poor in an effective economy with goods of low quality at high prices.” He continues: “[A] society with an efficient economy can afford to help its poorer citizens economically through voluntary charities or governmental assistance. Competition, in short, makes possible a better standard of living for everyone in a prosperous society.”

This paragraph, published the year before Acton opened its doors, presciently summarizes much of what our organization sought to accomplish from its beginning. It is with tremendous humility that I remember Russell Kirk on the 100th anniversary of his birth, thanking him for helping to forge the path that the Acton Institute continues to blaze. He is but one of the giants upon whose shoulders we stand.