This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom

Martin Hägglund | Pantheon Books | 2019 | 450 pgs

In his newest book, Martin Hägglund turns religious faith upside down. This Life constitutes a full-scale denial of the transcendent – on any level of human perception – and a declaration that religion is “unnecessary, ”“boring,” and worst of all, obsessed with “eternity.” Hägglund finds this last feature particularly odious, because religious faith calls people’s attention away from the values that he believes really matter – namely, the needs of the present life – in favor of an “other-worldly” consciousness that prevents them (and society at large) from experiencing true “freedom.” The necessary substitute for this misplaced faith in religious dogma, the author insists, is a “secular faith,” a “new” perspective on the value and extent of our finiteness. In this, he notes, his thought is indebted to the insights of the much “misunderstood” Karl Marx.

This Life is divided into six chapters intended to elucidate the nature of “secular faith” (Part One) and “spiritual freedom” (Part Two). The contents of Part One are organized under the intriguing titles “Faith,” “Love,” and “Responsibility,” which convey the author’s desire to mimic the Christian virtues of faith, hope, and love. However, he imbues them with an entirely secular meaning. Part Two is devoted to the “emancipating possibilities” of that “secular faith.” Its three chapters attempt to develop a philosophical argument for the primacy of the finite, reinterpret Marx’s critique of capitalism with a view to underscore the superiority of Marxist values, and argue that Marx – properly understood – facilitates democracy (or what Hägglund calls “democratic socialism”). Making these sorts of arguments will not be easy, and they will strike the reader as, in many ways, self-contradictory.

Hägglund’s disdain for religion stems in part from the presupposition that “eternal life” is “unattainable” and, in fact, “undesirable.”

Following a sweeping intellectual tour that finds its inspiration chiefly in Marx and Nietzsche, Hägglund’s disdain for religion stems in part from the presupposition that “eternal life” is “unattainable” and, in fact, “undesirable.” Hence, we should understand ourselves as mere mortals, focusing solely and intentionally on the present life. By this measure, “secular faith” is conceived as a life that is temporal, a life that will end and, hence, a life that should focus on material reality. The implication for Hägglund is that religious faith devalues our lives by restricting us in our present life through its eschatological or other-worldly values and concerns.

This sort of philosophy, of course, needs to be substantiated, since it flies in face of conventional thinking, as well as most people’s experience. Here, in marshaling support for his thesis, the author looks to a leading – if not the leading – materialist thinker of recent Western history: Karl Marx. After all, in Marx’s day a growing recognition was afoot that “we do not have to be subjected to the laws of religion or capital … but can transform our historical situation through collective action and create institutions for the free development of social individuals as an end itself.”

In attempting to develop his thesis, Hägglund will find it necessary to circumvent the most obvious obstacle: recent history. Thus, he offers the standard dodge that totalitarian regimes “failed to grasp the insights of Marx not only in practice but also in theory.” One might call this the old “Marx was misunderstood” strategy. For this reason, Hägglund argues that we must “retrieve and develop Marx’s insights in a new direction, ” in order to properly understand the nature and outworking of true “freedom.”

The blitheness with which Marxists circumvent the historical record would be less outrageous if it weren’t for the utterly tragic results in praxis that have followed Marxist thought on every continent. Where in the world, past or present, do we find nations in which the adoption of Marxist ideas has led to a flourishing culture? One is at a loss to find one unless, of course, Hägglund wishes to cite present-day Venezuela (which is conveniently ignored in his book). The most that Hägglund can do is point to Europe’s so-called “democratic socialist” nations, such as Sweden. Even these nations engage in a greater degree of market capitalism than Hägglund is willing to acknowledge. However, to argue for “democratic socialism” is to attempt to have it both ways. Here again we see the parasitic nature of Marxist-socialist thought, for in practice, no human beings or societies are capable of flourishing under its economic, political, and social policies.

Where in the world, past or present, do we find nations in which the adoption of Marxist ideas has led to a flourishing culture? One is at a loss to find one

But there is a reason for this failure – a reason which transcends strict economics. That reason is anthropological. For the materialist, the human person is to be understood solely in material – and hence “economic” – terms. The human person, devoid of the spiritual component, lacks intrinsic dignity and an attendant ability to flourish. And absent the spiritual component, which produces in human beings an awareness of that intrinsic dignity (based on the imago Dei), there can be no moral ecology in which societies function and cultures thrive.

Through his writings, Michael Novak reminds us of the triangle of systems that are mutually dependent on one another, interacting and creating the conditions for human flourishing. These three systems are the political culture, the economic culture, and the moral-social culture. Without the last, the former two suffer and collapse. Hence, the ecology of “freedom” that is so important to Hägglund is utterly impossible without a moral culture. And a moral culture is dependent on the religious impulse, as the Founding Fathers of this nation recognized, as Alexis de Tocqueville observed, and as every generation must learn – for better or worse. For this reason, religious freedom has been called the “first freedom.” If people are not free to follow the sacred rights of conscience – as is the tragic case in many parts of the world and in all nations that are committed to Marxist ideology – they have no chance of attaining any sort of “democratic” character, and they will be unable to flourish. Rather, they will be persecuted, imprisoned, tortured, or killed, since “freedom” is the right to disagree, and the state cannot tolerate any measure of dissent.

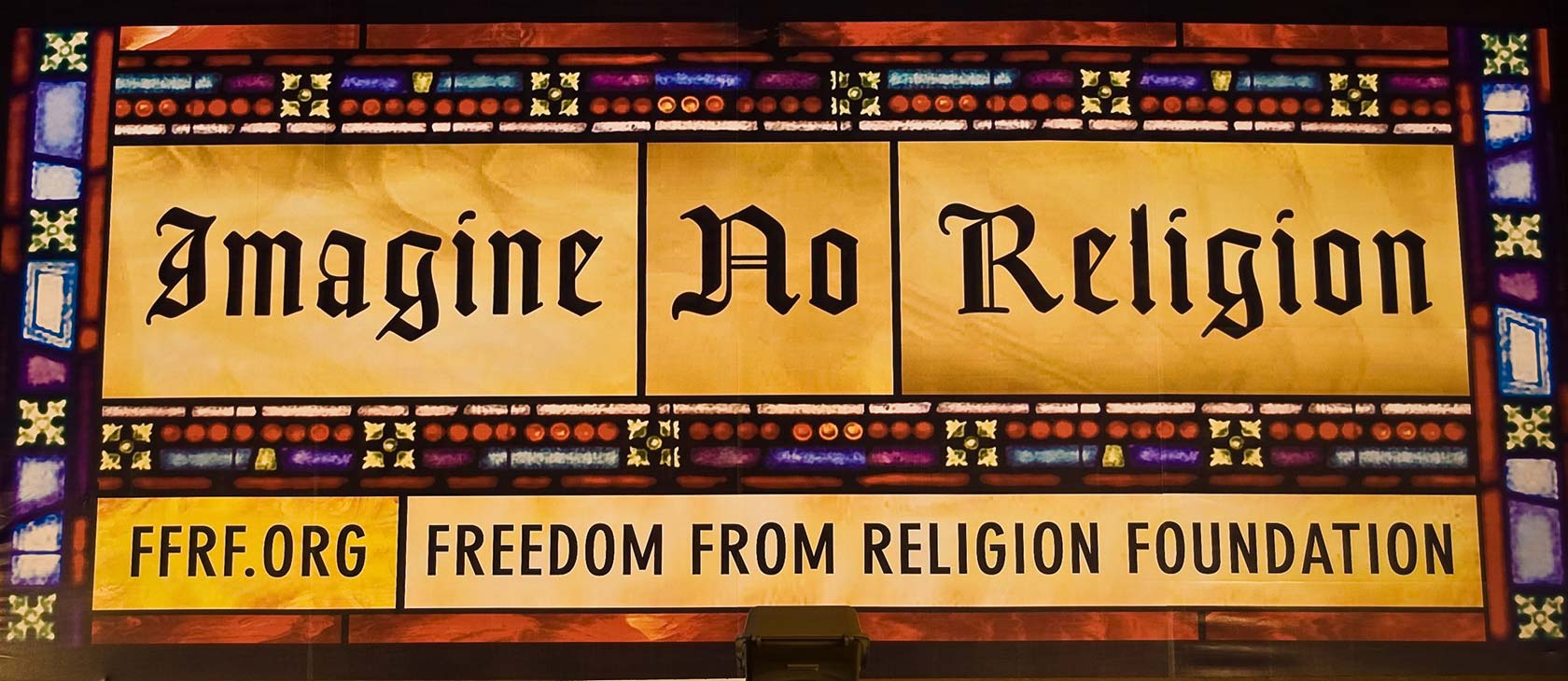

Like all heresy, Hägglund’s work begins with a perversion of the truth. From the standpoint of the reader, perhaps the most frustrating aspect of this tendency is Hägglund’s borrowing terms that convey value and meaning in a religious context and importing them into his arguments for a secular paradise. At the same time, Hägglund is to be applauded for at least being honest about secularism as a philosophy, for indeed it is a religion and it functions as a religion. Since secularism cannot be proven to be true, and since it cannot explain away the reality of the transcendent, it must make pronouncements by faith. Perhaps unwittingly Hägglund hereby undermines the secular argument which he and others would seek to advance: Secularism, too, proceeds on certain metaphysical assumptions, even when it is in denial of them at the theoretical level.

In the end, the secular outlook is to be embraced or rejected on the basis of faith. However, its standard problem is that it is essentially parasitic; that is, it can only exist where there is religious faith and only where claims to transcendent metaphysical reality already exist. Relatively speaking, then, if we view it from the standpoint of human history, secularism is a recent development. Like bacteria, it needs prior life to sustain any sort of “existence” of its own.

In the end, the secular outlook is to be embraced or rejected on the basis of faith.

Over the years I have thought long and hard about the current condition of European nations, perhaps because I married a European citizen and spent the early years of married life living in Europe. What has always struck me is the sheer rapidity with which European nations have become wholly secularized. This is true, not only of Scandinavian countries – the author of This Life is Swedish – and most of what is formerly Lutheran northern Europe, but also of the nations of southern Europe which historically are predominantly Roman Catholic. One gets the impression that European nations are competing to see which country can jettison its religious heritage the fastest.

In the end, the “democratic socialism” being advocated by Martin Hägglund does not, alas, lead to “spiritual freedom.” In fact, the European model of “democratic socialism” would appear to be in the early throes of a new subservience. Consider what Islamists have long predicted about Europe, and the possibility that in 50 years Europe could have an Islamic majority. Strangely, not a word about Europe’s crisis of character and its utter lack of values is found in This Life. Hägglund seems blissfully unaware that Europe may not be “European” for much longer. For into that secular vacuum – wherein people believe nothing, affirm nothing, and live only for the present (as Hägglund advocates) – has appeared another worldview. It is a metaphysical outlook that is decidedly religious and eschatological in orientation. It honors “martyrs” who go to their graves in order to transform European culture into a new religious despotism. This struggle, or jihad, for cultural ascent in Europe need not be violent, although it may – and in fact often does – require violence and intimidation. It is truly unfortunate that Hägglund seems unaware of the practical end to which his commitment to Marxist thinking and so-called “democratic socialism” leads. His call, as developed in This Life, to a “new secular vision” – a call to move “beyond religion and capitalism” – approximates an invitation to political, economic, and socio-cultural suicide. The path that he proposes leads to serfdom, repression, and poverty.

It has been said that the only place where Marxist thinking still exists in the West is in universities. The cynic might observe that this is the natural result when a young professor of comparative literature and the humanities at Yale like Hägglund – possessing no sense of historical memory and engaging no serious economic theorists of our time – starts writing books on “political economy” and “spiritual freedom.” But we must eclipse cynicism to point out that Hägglund is wrongheaded and misguided (when not utterly naïve) to revivify Marxist thinking about capitalism and deem it “misunderstood.” The proof, as they say, is in the pudding, and no one has contributed to more death, destruction, and human misery in our world during the last 150 years than Karl Marx. Hägglund is correct to identify secularism as a faith; at least in this regard, he is honest. He is wrong – dead wrong – to blithely insist that it leads to “spiritual freedom.” It will lead, rather, to a Hell on earth, as we have tragically witnessed again and again for more than a century.