What we mean when we use the word “Black” (and whether or not we capitalize it) causes constant confusion in American life. We are liable to contrast Black with white, and to treat the two terms as though they belong to the same category: race. But this is a mistake. As a matter of historical fact, Black Americans formed separate cultural institutions because they were excluded from white institutions or forced to be subordinate within them on account of the color of their skin. But those separate institutions, greatest among them the Black church, grew into unique and powerful cultural forces that shaped Black American life in ways that are both quintessentially American and distinctively Black. As Denzel Washington says, “It’s not color; it’s culture.”

The role of the Black church in the lives of Black Americans has much to teach all American Christians—first of all, why there needed to be a “Black” church at all. But is it time to look beyond self-segregated institutions in the hope of forming one multiracial, multiethnic institution?

“White,” on the other hand, is a mere legal category. Culture tends to be regional; the vast majority of Black Americans hail from the southeast, while whites are found in every American region. It’s not so much that white people are punctual as that the northeastern great-great-great grandchildren of the industrializing Puritans are punctual, while people from agricultural economies the world over are more relaxed about time. It’s not at all that Black Americans are more egalitarian and whites are more hierarchical as that northeastern elites who draw up these lists about “whiteness” are egalitarians themselves and so want to associate their own culture with minority culture. Sadly for them, Black Americans, like most southerners, are quite hierarchical, as is evident in parenting styles, in the use of honorifics when addressing one’s elders, and in ecclesial structure. In how many white churches, one might ask, do we refer to the wife of the pastor as the First Lady? And so, as it turns out, whiteness is not a particularly helpful category when it comes to describing a culture. Rather, the term is used in some academic circles to refer to the legal category that could, throughout much of the 20th century, afford one the fullest set of legal rights. Unsurprisingly, anyone who could make a case for themselves clamored to get into this category, including many immigrant communities that had never been thought white before.

Distinguishing the use of the term “Black” as referring to a particular slice of American culture and “white” as referring to a historical legal category helps us solve the conundrum of that common online query, “What if we said the same thing for white people?” That is, what if we had a “Buy White” day, celebrated white excellence, or had a White Student Union in our university? The fact that such questions are patently absurd proves the culture-not-race point. Black Americans are celebrating a shared historical experience, a history of cultural solidarity in the face of real oppression, and the particulars of a unique cultural legacy. While exclusion by whites provided the impetus for this cultural formation, oppression is by no means its central characteristic. That honor goes to something far more substantive: the Imago Dei doctrine of the Black church. C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya, authors of The Black Church in the African American Experience, call the Black church the “cultural womb” of Black America. It is this institution and this theological emphasis that gives rise to so much else, including some of the largest social organizations in the history of the United States, some of the most globally influential music in the history of the world, and one of the most ethically sophisticated political movements in all of history. In spite of the decline of all church attendance across the United States, an overwhelming majority of Black Americans today identify as Christians, and they are the most likely demographic group to say they believe in God, pray, and read the Bible.

We need the Black church. All of us. We ought to be celebrating it, learning its history, and bringing its legacy to bear for current struggles, both in the church and in our common life together as Americans.

Why the Black Church?

Having grown up in a multiethnic church with a Black pastor whose background was in the Black church, I assumed that I had a passing familiarity with this tradition. But after doing the research for the chapter on the Black church in Black Liberation Through the Marketplace, I realized I was far more ignorant than I had suspected. I had assumed, for instance, that Black enslaved people became Christians through the efforts of slaveholders, but this is almost completely false. Some of the enslaved were already Christians, as we see with the Stono Rebellion of Portuguese-speaking Catholics in South Carolina in 1739. Many southern planters were fairly unchurched Anglicans who knew just enough Bible to know that Christian slaves could make a compelling biblical case for their freedom based on various warnings to the Hebrews never to enslave one’s brothers and sisters. The planters were right about that, by the way; this is exactly what the enslaved argued after conversion! Rather than being evangelized by their slaveholders, some of the enslaved converted at the tent meetings of evangelical revivalists, and they went on to evangelize one another when they returned to the plantation. As a result, the historical Black church is Baptist and Methodist, as these groups made up the majority of revivalists. (Pentecostalism doesn’t arise until the early 20th century and began as an interracial movement.)

In spite of the decline of all church attendance across the United States, an overwhelming majority of Black Americans today identify as Christians, and they are the most likely demographic group to say they believe in God, pray, and read the Bible.

Slaveholders were often furious, beating zealous new converts for praying with and preaching to one another. When white plantation missionaries came to preach to the enslaved, their every word was vetted by the masters, so that their preaching consisted of warnings against theft and disobedience with nary a word about Jesus Christ. They brought with them religious pamphlets full of pictures of white Jesus, white Moses, and white Paul, too. This, and not Christianity in general, was the genesis of the phrase “white man’s religion.” The enslaved were referring quite literally to the preaching of a false gospel of obedience to whites. In contrast, their own secret, nighttime gatherings of worship in “hush harbors” elevated their status as children of God, their joy in the belief that Christ died for them, and their aspiration for the same freedom that the God of Israel had provided to the ancient Hebrews. It was from these early meetings of the Black church that the tradition of the spirituals emerged, with their explicit celebration of spiritual freedom hiding the implicit longing for physical freedom. Frederick Douglass’ account of his own conversion in his second autobiography is representative. Evangelized and discipled by his dear friend Uncle Lawson, he was ecstatic at the thought of salvation by Jesus and wanted nothing more than to spread the good news. He and Uncle Lawson prayed for and believed that he would someday be free. He was actively persecuted for his faith by his slaveholder, and he contrasted his own spiritual formation with the flaccid teaching that he overheard from his mistress’s pastor.

In Slave Religion, Albert Raboteau argues that the growth of the Black church in secret became the central source of self-esteem for enslaved Black people. It gave them the dreams of freedom that inspired them to take hold of it when the chance finally came. It gave them the intense desire to learn that catapulted their literacy rates from near-zero at emancipation to 80% in 1930. The Black church created a space within which Black people’s leadership mattered, not just to one another, but to God Himself. Their persecution by their slaveholders for their religious faith aligned them with the martyrs of Acts and placed some of them among the “great cloud of witnesses” attested to by Paul.

It’s worth mentioning that the Black church is almost certainly also the genesis of the term “Black joy,” which never ceases to puzzle white people unfamiliar with this history. The revivalists noted immediately that while white converts would wail and moan over their sin, Black converts, though also grieved by their own sin, were more likely to respond with ecstatic joy, leaping and shouting, praising God. It may be hard to convey what an effusion of intense joy came over those who were just then learning that the God of the universe made them in his own image; that God loved them so dearly that he would take on flesh and die for them; and that they would rule with him in eternity, even judging angels! Those who had been told again and again that they were not even worthy of freedom or citizenship were now being told that they were worthy of the status of children of God and citizenship in the kingdom of heaven. The revivalists welcomed their enthusiasm, and many Baptists and Methodists initially accepted Black believers as equal members of the church before the intractability of the slave system wore down their lofty principles.

The Black Church as Cradle of Entrepreneurship

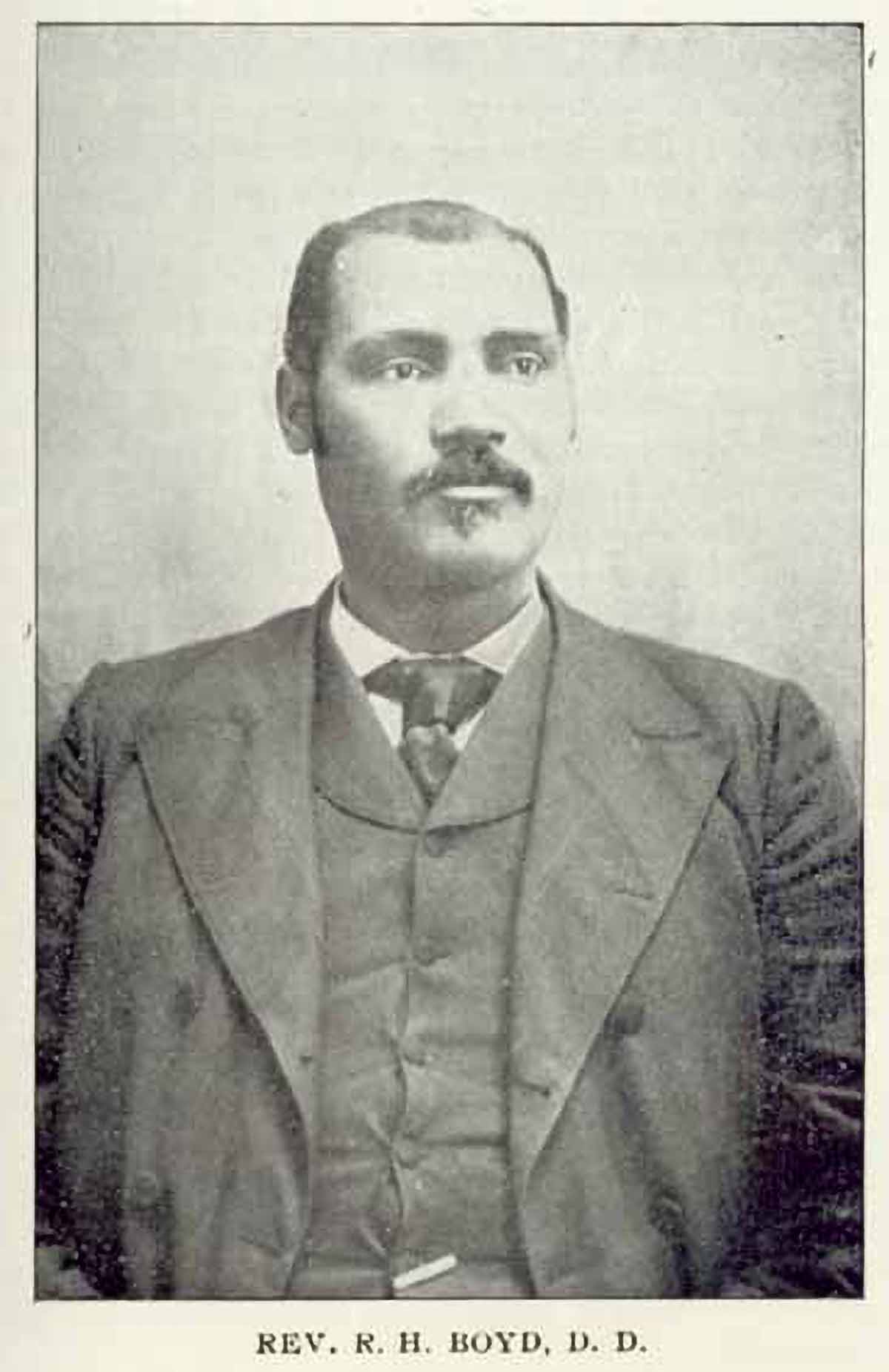

One can imagine the images, the theological emphases, and the hymn lyrics that might suffuse all white-produced materials for churches, even those with a significant number of Black Christians sitting in pews. Were these materials affirming the dignity of Black people? Were they reflecting the artistic contributions of Black musicians or the insights of Black preachers? Almost certainly not. Enter Richard Henry Boyd.

Born Dick Gray, after his slaveholder, Richard Henry Boyd supported his slaveholder and his slaveholder’s sons in the Civil War. He managed their farm and cotton sales for a time after the war but also changed his name and learned to read. Like so many other formerly enslaved people, Boyd rushed to marry and to officially join a Black church in the late 1860s, privileges that had been denied to the slave population until then. He became a Baptist minister soon after and led congregations throughout Texas. Boyd organized the Texas Negro Baptist Convention as well as several new Black Baptist churches while also taking advantage of the opportunity to purchase cheap land in the area. While doing so, he noticed that Sunday school material, as well as the curricula provided for the Freedmen’s schools throughout the south, were entirely written and published by whites. The organizations doing the publishing—the American Baptist Home Mission Society and the American Baptist Publishing Society—had been anti-slavery, so not all Black Baptists were as animated as Boyd about starting separate publishing ventures. But Boyd was sure that the materials wouldn’t serve Black children well. After reaching an agreement with the Southern Baptist Convention, he convinced several important Black Baptist organizations to buy their materials exclusively from him. All this was fairly controversial, as it caused a major power shift away from the American Baptist Publishing Society, with some even accusing Boyd of arranging things merely to further his own business interests.

Upsetting a church publishing duopoly sounds nefarious enough unless we reflect on the fact that the overarching white religious body published only white authors, white musicians, and white Sunday school material. Once again, this isn’t primarily about the color of anyone’s skin, but about Black culture formation through the Black church. What Boyd found objectionable was the way that white publications failed to serve the needs of Black families and children in Black churches. So Baptist church materials were in a very real sense shutting out Black Baptist contributions. The secondary effect of this was that Black creators were shut out of any economic benefit in providing these materials as well. So the problem was both cultural and economic in nature. And it should be noted that Boyd, in true Booker T. Washington fashion, went on to promote Black creators of all kinds through his new publishing company, in ways that indirectly shaped the popular rise, for instance, of Black gospel music.

Boyd went on to promote Black creators of all kinds through his new publishing company, in ways that indirectly shaped the popular rise, for instance, of Black gospel music.

Nevertheless, Boyd’s choice to break away was highly controversial even within his own community, reflecting a philosophical debate between Black Christian separationists and other Black Christians who thought that these sorts of group-focused efforts were merely a distraction from the main work of the church, namely, evangelization. But the term “separationist” probably sounds more militant than it really was. Those Black Christians who felt the need to build specifically Black institutions for Black people still saw white Christians as true brothers and sisters in Christ and were often happy to ally Black institutions with white ones when it made sense to do so. It was less about a principled commitment to separation as much as it was about carving out space for their own culture and culture makers in a white-dominated world that wasn’t quick to include or promote them. It was the best response to an unideal situation.

In a parallel way, Boyd objected to white-manufactured Black dolls, not because they were made by white companies, but because they were of “that disgraceful and humiliating type” that children responded to by using them as “a scarecrow.” Boyd launched the National Negro Doll Company in 1911. In Baptists in America, historians Thomas Kidd and Barry Hankins claim that he probably had more influence in promoting Black dolls than the better known and more secular Marcus Garvey (who launched his own efforts a decade later). Surely Boyd’s influence on the rise of the new dolls as a point of Black pride in households across America depended heavily on his influence within the church, typified by the 1908 National Baptist Convention resolution to remove Caucasian dolls from the homes of every “self-respecting Negro.”

Boyd’s requital of white exclusion speaks to the broader debate today over focusing energy promoting things—whether church-, business-, or education-related—that are specifically Black. This impulse splits down the middle. True, militant separationists who have no confidence in an integrated American future ought to be contrasted with those heirs of the Black self-help tradition who want to support Black creators in order to edify a population that is still sloughing off the legacy of political and financial exclusion. Kidd points out that separatism arose quite specifically in response to the “hardening of racial segregation and black disenfranchisement in the final two decades of the [19th] century.” We often forget that racism and racial segregation got much worse after Reconstruction, and it was nigh 100 years before we can safely say that racial healing was well underway. Cultural consciousness is not the same as racial division. Therefore, it’s not necessary to condemn Black Americans for finding ways to support one another when they are still in the process of correcting damaging racial ideas and closing the racial wealth gap.

Boyd was solidly in Booker T. Washington’s camp when it came to “casting down your buckets where you are.” A serial entrepreneur and highly financially successful, he never questioned the promise of economic uplift through Black self-help in America. When a group of nonseparationists (cooperationists) formed the Lott Carey Foreign Mission Convention, disagreements over how to handle relationships with white Baptists didn’t stop Boyd from joining his organization—the National Baptist Convention of America—to theirs in cooperative missionary efforts. Nor did Boyd hesitate to work with white Baptists once the Black institutions were well established. The camp we now call the “separationists” might better be described as Black culture-preservers. Kidd describes how Black Baptist women’s organizations, for instance, “saw no contradiction between working both in favor of Black separatism and in conjunction with white Baptists to advance female Baptist enterprises.” So-called separationists saw that membership in majority-white organizations would always mean the subordination of their creative efforts and theological emphases, so they created their own opportunities. Confident in the solidity of what they had built, they still joined happily with whites in common Baptist goals.

Mobilizing Massive Organizations

What may prove shocking to many about the Black American church is how massive their organizations were, often dwarfing parallel institutions in the white church. There are towns in the south whose Black Baptist churches pre-date any white Baptist church in the area. Various groups emerged over the years, but Black Baptists displayed great solidarity, even between separationist groups and cooperationist groups, in their mission efforts. In 1895 they finally joined together to form the National Baptist Convention, reaching 2.2 million members by 1906. Consider that, in 1905, the membership of the white Southern Baptist Convention was 1.9 million, and this was at a time when the Black share of the United States population was several percentage points lower than the current 13%. Indeed, Black Baptists prided themselves on their unity, contrasting themselves with white Baptists who had split over slavery.

Today the NBC boasts 8 million members and is second in size only to the Southern Baptist Convention (at 14 million members) among all American denominations. Alas, disputes over Boyd’s control of the ever more influential National Baptist Publishing Board led to his ultimate split with the NBC, to form the National Baptist Convention of America, sometimes referred to as “Boyd’s Convention.” After all, by 1906 the NBPB was the largest Black publishing company in the United States. It was the first to publish the old Negro spirituals and played a seminal role in the popularization of Black gospel music through the publication of Golden Gems and The National Baptist Hymnal. Though never rising to the numbers of its parent, the NBCA today boasts 3.1 million members. For comparison, the American Baptists (formerly known as the Northern Baptist Convention) boasts only 1.3 million members.

As W.E.B. Du Bois pointed out, Black churches are “curiously composite institutions, which combine[d] the work of churches, theaters, newspapers, homes, schools and lodges.” In Kenneth Clark’s interview with James Baldwin, Baldwin explains the way his parents’ loyalty to the church was typical of that generation: Their “relationship to the church was very direct because it was the only means they had of expressing their pain and their despair.” That meant that Black church organizations had a deep personal relevance, and therefore a solidarity, that could out-compete the white church in certain ways. Kidd cites an account of the Black church in Virginia: “There was not an evening or afternoon that had not its meetings, its literary or social gatherings, its picnic or fair for the benefit of the church, its Dorcas society, or some occasion of religious sociability.” The fulfillment of overlapping social needs in church extended to political organization as well. With so much social capital flowing out of the church, it’s no wonder that Black Americans report higher rates of religiosity and genuine belief than their white counterparts, and that Black denominations have remained relatively unified. We should also note that the United States is an unusually religious place all around, at least in comparison to other economically developed nations. This may very well be due, in part, to the deep commitment of its minority communities to their religious heritage.

While white Christians—both theologically progressive and conservative—often associate racial or ethnic consciousness with theological liberalism, Boyd’s NBCA has maintained a stringently orthodox faith, maintaining male-only ordination and traditional Christian sexual ethics. Even more fascinating, they have pursued ongoing racial reconciliation efforts through cooperative endeavors with the Southern Baptist Convention and the Cooperative Baptists. White Americans, whether on the left or the right, may be too liable to assume that Black racial consciousness among Christians is some kind of absolute philosophical commitment. A deeper grasp of American history shows that Black Christians always desired the fullness of spiritual sibling-hood with their white brothers and sisters. The denial of such came from the white church, causing some Black Christians to protect their own spiritual well-being by creating separate institutions. That practical choice organically led to the formation of distinct religio-cultural practices. The hope of reconciliation, however, never died. How does it stand today?

#LeaveLoud

Many predominantly white denominations embraced racial reconciliation efforts in the 1990s, seeing such actions as a basic correction of past injustice and harm, with some of the most conservative movements of the time, including the Promise Keepers, the Presbyterian Church of America, and the Southern Baptist Convention, getting on board. Denominational statements were published, both apologizing for past racial oppression and exclusion and committing to racial healing. Nevertheless, many have soured on such efforts recently in ways that remind us of the separationist/cooperationist debates of more than a century ago. While the most enthusiastic reconcilers formed multiethnic churches, this approach raises the question of how to think about those historical institutions that were formed as an important haven for Black people. (The same could be said for immigrant churches.) Are these institutions now to break apart so that their members can be scattered among the more predominant white churches in order to make them diverse? Perhaps the phrasing of that question is a giveaway; after all, why shouldn’t white people go to ethnic churches to pursue racial reconciliation? If that sounds absurd, it’s no more absurd than asking Black and immigrant Christians to participate in forms of worship and cultural practices that are foreign to them.

Ultimately, the greatest complaint from Black Christians about multiethnic churches is that they too often devolve into white churches with a smattering of other people in attendance but with white people in charge. It’s difficult for members of the majority culture to imagine subordinating the way they do worship or preaching to a minority leader. My own church is multiethnic, and great things are happening there, but the leadership is majority Black. As Black people are only 13% of the population, most white people won’t be able to have this experience.

Ultimately, the greatest complaint from Black Christians about multiethnic churches is that they too often devolve into white churches with a smattering of other people in attendance but with white people in charge.

The complaint about tokenism in the multiethnic church movement recently led to the #LeaveLoud campaign run by Jemar Tisby’s The Witness. Tisby came to the conclusion that white Christians weren’t going to humbly listen to and learn from Black leaders in multiethnic churches, so it was better simply to go. Similarly, Black Baptist pastor Charlie Dates had joined the Southern Baptist Convention in great hope after their MLK50 conference in 2018 celebrating the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. Older members had warned him against this decision, but he assured them that their fears were based on “the old Southern Baptists” and that a new day was dawning. Only a few years later, he felt that he had to admit to them that he had been wrong. SBC leaders argued that the only moral thing to do was to vote for Trump, and six SBC seminary heads chose the closing of 2020—the year of George Floyd—to declare that critical race theory was unbiblical and not allowed in their schools. Since writers associated with CRT seemed to be the only well-known scholars doing the historical digging on de jure and de facto segregation, the SBC had passed a resolution declaring that, while the philosophical underpinnings of CRT were objectionable, it was still possible to learn something from its scholars. But this resolution was later overturned because of opposition from an ultra-conservative faction that failed to grasp that the secular, intersectional association of racial issues with unorthodox views on sex and gender did not align with the vast majority of Black churches. The American Black church has always been awake to issues of genuine racial oppression while maintaining a high view of scripture and deeply traditional understandings of maleness, femaleness, and marriage. Since the Black church has never quite fit into our political binary, the protesting faction assumed that interest in the racial history work from some academics was a slippery slope into affirmation of homosexual acts and transgenderism. The failure to appreciate the uniqueness of the Black American blend of values and concerns is endemic.

I am neither a fan of Tisby’s alliance with third-wave anti-racism nor of critical race theory, and yet I can understand Tisby’s and Dates’ frustration. If the response of white Baptists was to reject critical pedagogy but actively replace it with another account of historical Black oppression, white members could presumably overlap significantly with Black members, even if they maintained different political leanings on secondary matters such as economic policy. Rather than retreating from the conversation about America’s history of racial oppression, conservatives could contribute to that conversation by highlighting the role of the state in socially engineering segregation, attacking Black property and contract rights, and undermining Black economic advancement through well-meaning but foolish policies. While one often hears the refrain from conservatives that, of course we should teach the lamentable elements of our history along with the good, one has rarely seen conservatives commit real time and effort to this task. In the midst of their own retreat from the historical work, they complain that the left controls the narrative. The statement of the seminary heads, particularly given its timing, felt like pandering to the ultra-conservative wing rather than prioritizing racial reconciliation efforts.

Maintaining cultural distinctives through separate institutions may simply be part and parcel of thick civil society institutions, including the church.

But perhaps more relevant to the question of racial reconciliation is whether multiethnic churches were ever the solution. There’s certainly nothing wrong with having such a church, but it may be asking too much to artificially push people in the direction of such projects. After all, the ethnic diversity and spiritual unity displayed in Revelations 7 are promised in the kingdom of God, when all our disparate songs will miraculously blend in perfect harmony. Until then, however, maintaining cultural distinctives through separate institutions may simply be part and parcel of thick civil society institutions, including the church. The desire to somehow reconcile them all in one worship service may simply lead to the poor execution of good traditions in music, preaching, and liturgy. It may constitute a denial of our embodiment, which limits us to this place, this culture, and this tradition. None of these claims denies the possibility of sweet partnerships between churches of different ethnicities, and these could facilitate mutual understanding and racial reconciliation without watering down the particular practices that have meant so much to the process of spiritual formation in a given tradition. Is this separationism or just cultural preservation?

Like minister and entrepreneur Richard Henry Boyd, I think Christians should build the institutions they need to edify the communities they are in, while maintaining hearts full of hope and openness to all other Christian believers. Organic, multiethnic churches will certainly emerge as our neighborhoods become more diverse. For those who choose to remain in the historical havens of Black and immigrant churches, partnerships with majority-culture churches can help us to move ever closer to that beautiful picture of worship that our Lord himself revealed to John:

After this I looked, and behold, a great multitude that no one could number, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, clothed in white robes, with palm branches in their hands, and crying out with a loud voice, “Salvation belongs to our God who sits on the throne, and to the Lamb!”