It is always hard to know where to begin with Thomas Jefferson—or where to end. In that respect, he is not that different from a great many other talented political figures in our history. The politician’s art all but requires a talent for enigma, an ability to draw in disparate followers and factions while remaining mysterious, un-pin-down-able, containing worlds of seeming contradiction within both public image and private life. Think of the tangled moral complexity of men like Woodrow Wilson, Lyndon Johnson, or Martin Luther King Jr., for example. In each of those cases, and there are a great many more that could be adduced, one must find a way to account for extraordinary moral lapses in careers that were generally successful, built around high ideals that largely benefitted the nation.

The third president of the United States is another victim of our era’s small-minded rage against the very idea that imperfect men can still be heroes—and that we badly need such heroes.

By Thomas Kidd

(Yale University Press, 2022)

That this moral tangle was especially characteristic of Jefferson has long been so undeniable as to be axiomatic. His illustrious public career as an American statesman and visionary spokesman for the American experiment in self-government, as a man whose words have inspired peoples all over the world, has to be balanced against a private life that had such grievous faults that they have, in recent years, threatened to bury his reputation entirely. It was not that long ago that the biggest annual fundraising event in the life of local Democratic parties was called the Jefferson-Jackson dinner, named after two of the uncontested stars of the party’s early history, Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson. Now… not so much. The dinners are still being held, but the names have been changed. Jefferson and Jackson have gone from being partisan heroes to being personae non gratae. Even one of Jefferson’s incontestable virtues, his sterling record as an advocate for free speech and intellectual inquiry, has come into bad odor, as the academy, and even the American Civil Liberties Union, has soured on the ideal of free expression and turned against it.

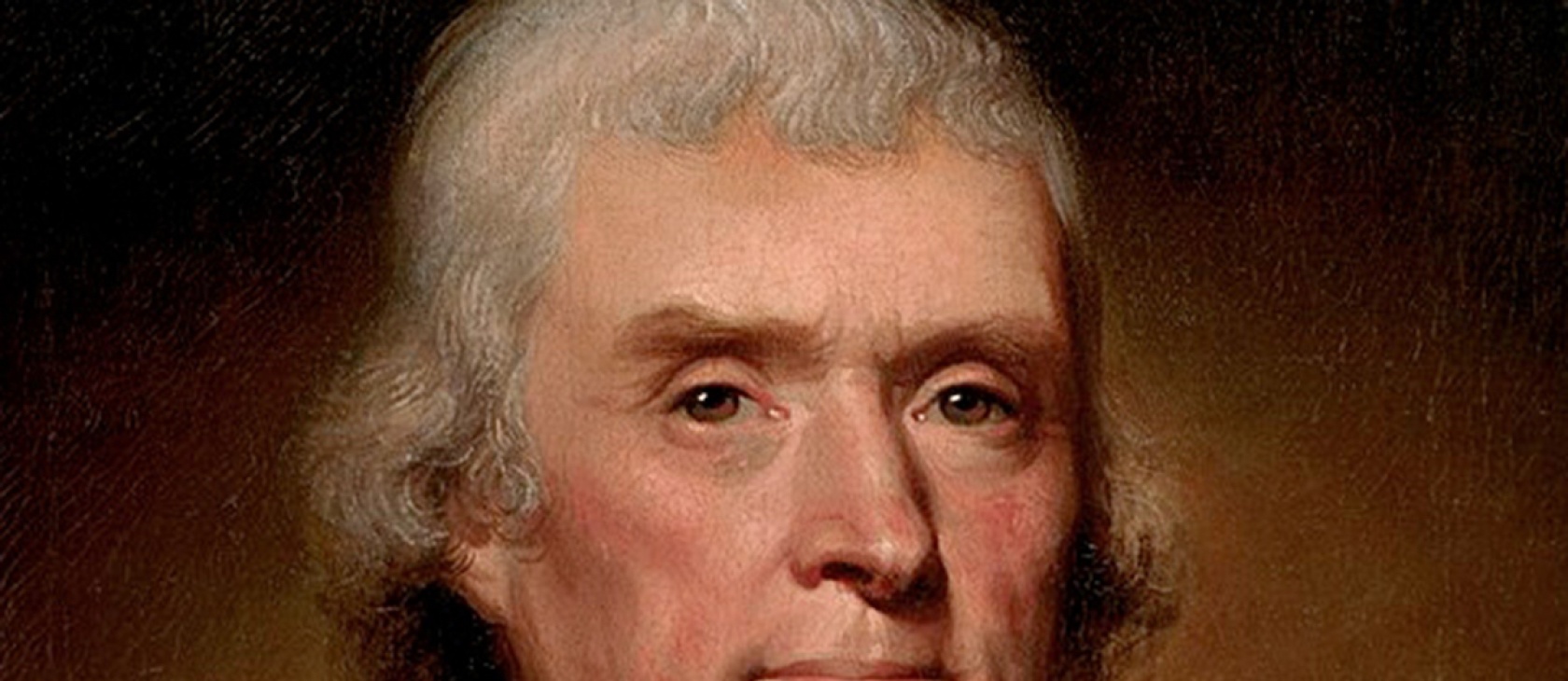

What a fall from historiographical grace there has been. Jefferson’s early biographer James Parton described him in 1775—one year before he wrote the Declaration of Independence—as “a gentleman of thirty-two, who could calculate an eclipse, survey an estate, tie an artery, plan an edifice, try a cause, break a horse, dance a minuet, and play the violin.” And at that point in his life, he was just getting warmed up. The spirit of Parton’s words was still alive as recently as April 29, 1962, when President John F. Kennedy, in welcoming a group of Nobel Prize winners to a dinner in their honor at the White House, uttered the following words: “I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House—with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.”

But no such admiration was in evidence in Charlottesville, when Black Lives Matter protesters placed a black shroud over the statue of Jefferson in front of the Rotunda, or in Portland, Oregon, where mobs used axes and ropes to topple a statue of Jefferson, or in New York, where a statue of Jefferson was removed from City Hall. What a difference a half-century makes! And yet, leaving aside the lawless destructiveness of a great many of the protesters, it cannot be doubted that their protests were in part a product of a sea-change in public opinion, a change that has made Kennedy’s unrestrained admiration for the man far less tenable. Only a small part of this change has occurred because of new discoveries about Jefferson’s life. More of it has come from a changed moral perspective about faults of which we already knew, particularly relating to his ambivalent attitude toward slavery, an institution he criticized severely but from which he was not willing to extricate himself personally. The charge of hypocrisy does not seem unwarranted.

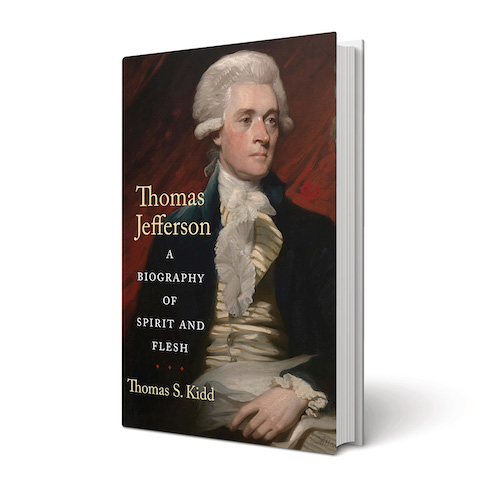

So how do we reckon the balance and arrive at a just assessment of the man? That is the task Thomas Kidd has set for himself in this lucid, balanced, and searching account of Jefferson’s life and of the contradictions he lived out. One of our finest and most prolific historians of early America, Kidd is especially well known for his important work in the history of early American religion, especially evangelical Protestantism, and his biographical accounts of such figures as George Whitefield, Patrick Henry, and Benjamin Franklin. He is attuned to the religious universe of the times and is able to show how a figure like Jefferson, despite the insistence of generations of historians on associating him with deism, atheism, and other departures from orthodox Trinitarian Christianity, was deeply affected by the religious currents of his day and wrestled with questions of faith and providence far more often and far more deeply than the conventional view of him would suggest. His Jefferson is, if possible, even more complex than any Jefferson we have had before. I would place this book alongside the truly magnificent full-scale biography of Jefferson by John Boles, Jefferson: Architect of American Liberty, and the excellent scholarship of Kevin R.C. Gutzman, as an indispensable guide to the understanding of Mr. Jefferson, the American polytropos.

A COMPLICATED MAN

Again, where should we begin in assessing this complicated man? Should we start by recounting his political accomplishments over four decades of public service, ranging from his entry into the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1769 to his retirement from public life in 1809, after two terms as the third president of the United States?

Or do we stress instead his influence in the world of ideas, through his powerful writings in support of American independence—the greatest of these being, of course, the Declaration of Independence itself, with its stirring invocation of the God-given rights of every individual human being—words that changed the course of human history and continue to do so today?

Or his card-carrying status as a figure of the Enlightenment, with a keen and unflagging interest in natural science, as evidenced by his service as president of the American Philosophical Society from 1797 to 1815, years that overlap his entire tenure as president of the United States?

Or his love of architecture, as embodied in the graceful neoclassical home Monticello that he designed and built for himself near his Virginia birthplace on what was then the western edge of settlement?

Not to mention his overwhelming passion for gadgetry, which invariably impresses visitors to Monticello, who nearly always remember the revolving bookstand, the dumbwaiter, the copying machine, the automatic double doors, the Great Clock, the triple-sash window, and countless other gizmos that the ever-inventive Jefferson himself either designed or adapted.

Of how many other men can it be said that their having served two full terms as president of the United States was in the second or third tier of their accomplishments?

And what about his founding of the University of Virginia in nearby Charlottesville, whose serenely beautiful central campus he also designed? Or his great contributions to the cause of religious and intellectual liberty, which for him were essential to the dignity of the individual person and central to the work of a great university?

Should we stress the fact that Jefferson, that inveterate designer, even designed his own tombstone and specified the only things it was to say about his life: that he wrote the Declaration and Virginia’s Statute of Religious Freedom, and that he was Father of the University of Virginia? Of how many other men can it be said that their having served two full terms as president of the United States—which I think we all agree is no shabby achievement!—was in the second or third tier of their accomplishments?

Kidd gives adequate attention to all these marks of distinction in Jefferson’s life. But the underlying spirit of his account of Jefferson is more critical, more insistent that his failings should be highlighted more than they have tended to be in the past. Hence we begin his book hearing primarily about Jefferson’s complexity, his contradictions, his shortcomings, the negative aspects of Jefferson’s life and career that simply cannot be denied or wished away. Let us recollect what those undeniable shortcomings were.

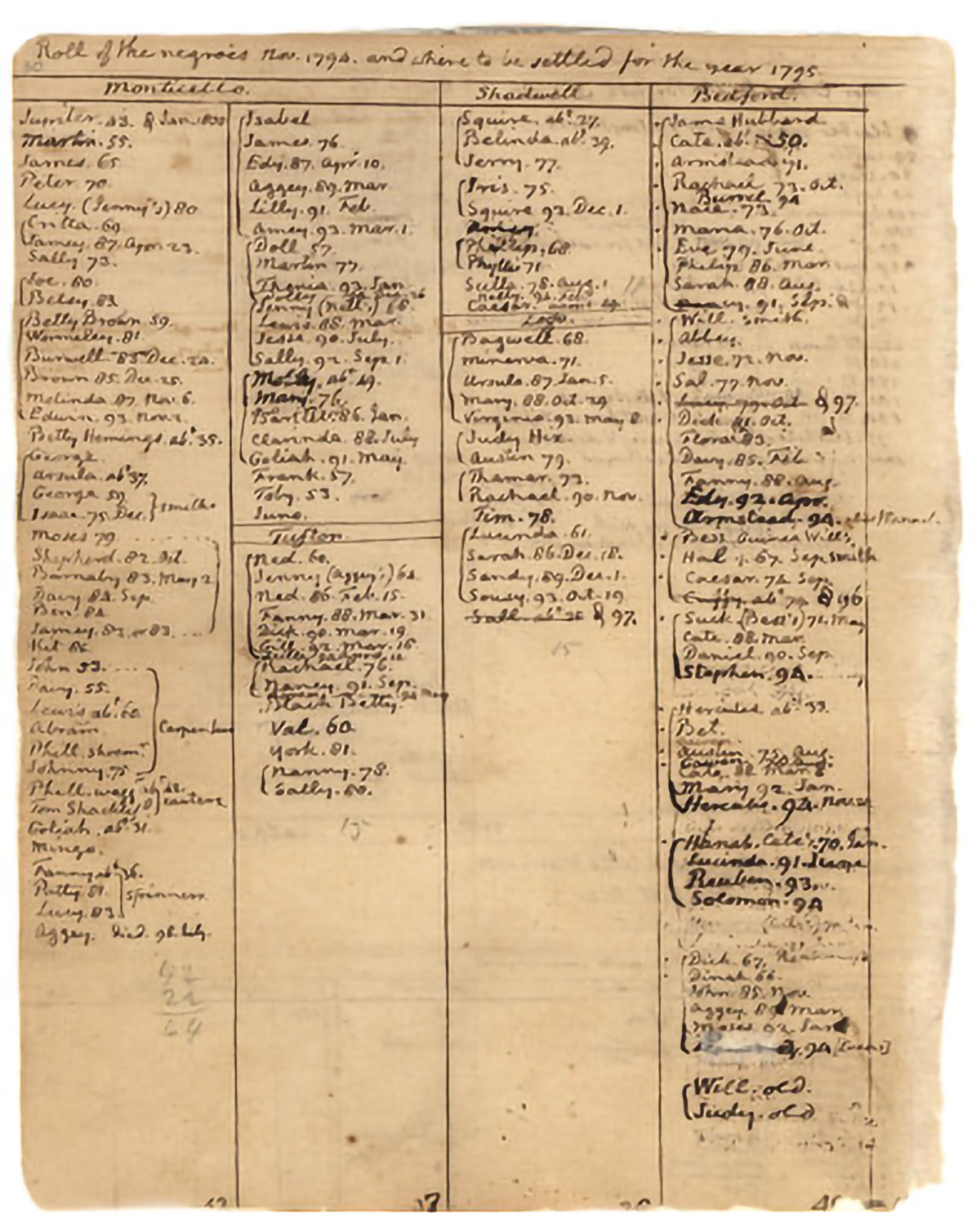

No one can deny that, although Jefferson opposed slavery in theory, he consistently failed to oppose it in practice, including notably in the conduct of his own life at Monticello.

No one can deny that Jefferson’s racial views, particularly as expressed in his book Notes on the State of Virginia, are appalling by today’s standards.

No one can deny that Jefferson often practiced a very harsh brand of politics. His famously conciliatory words “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists” in his First Inaugural Address were quickly belied by his ferocious partisanship, which was relentlessly aimed at stigmatizing the Federalist Party and driving it out of existence. Up until the election of 1800, the principal figures in American political life had hoped (foolishly, as soon became clear) that the country could escape the scourge of partisan politics. But no one made the party system work with more ruthless efficiency than Jefferson. He embraced the role of party leader and, unlike Washington and Adams, appointed only men of his own party to the top Cabinet positions. Over the two terms of his presidency, he had great success in establishing Republican dominance and putting the Federalist Party out of business.

Nor can one deny that his greatest act as president, the Louisiana Purchase, and his worst, the Embargo Act, both represented a complete repudiation of his most basic principles about the dangers of big government and strong executive authority. He could hardly be described as a man of firm and invariant principles.

These are not small flaws, nor are they the only ones. Kidd especially insists that we take more seriously the corrupting influence of Jefferson’s personal lifestyle, which was dependent not only upon slavery but the sexual exploitation of the enslaved, including his relationship with Sally Hemings, by whom it is alleged (and the allegation remains contested) that he fathered children. And Jefferson’s lavish personal spending, in contrast to his budget-tightening approach to public policy, was one of the factors that ensured his dependence upon the institution of slavery and made him ever less able even to consider manumitting his slaves. Kidd ends his book with a bleak depiction of what became of Jefferson’s little world once he had departed it. He had spent like a drunken sailor and made no provision for the future. I don’t think any of Jefferson’s biographers has made a better case for the need to take these personal failings much more seriously than we have. I am persuaded that Kidd is right to insist on it.

IMPERFECT HEROES

Still, if I have a criticism of this fine book, it would be that its moral acuity sometimes shades, ever so slightly, into present-minded moralism. It is hard to resist the temptation to judge Jefferson by our own standards. What makes him morally culpable in our eyes is the fact that we can see that he knew better. He was living at a moment of profound transition in the moral sensibility of the world, and it is small wonder that he could be advanced far beyond his times in some respects and retrograde in others.

Jefferson is, I believe, one of the principal victims of our era’s small-minded rage against the very idea that imperfect men can still be heroes—and that we badly need such heroes. (And furthermore, that imperfect human beings are the only heroes we can ever hope to have. There is nothing else on offer!) We have been living through an era that feels compelled to cut the storied past down to the size of the tabloid present—and then to cancel it altogether. The time has come for this self-congratulatory myopia to change.

For when all is said and done, Thomas Jefferson deserves to be remembered and revered as a great intellect and great patriot, whose worldwide influence, from Beijing to Lhasa to Kiev to Prague, has been incalculable, and whose belief in the dignity and unrealized potential to be found in the minds and hearts of ordinary people is at the core of what is greatest in the American democratic experiment. It is in this sense that James Parton was absolutely correct in making the following proclamation: “If Jefferson is wrong, America is wrong. If America is right, Jefferson was right.”

Of course, we want to know more than Jefferson’s words; we want to feel that we know the man himself. But that is exceptionally hard with Jefferson. He eludes our grasp. He may well have been the shyest man ever to occupy the office of president, awkward and taciturn except in small and convivial settings, such as small dinner parties, where he could feel at his ease and shed some of his reticence.

He loathed public speaking, giving only two major speeches while president, and none on the campaign trail. He often felt that the work of politics ran against his nature and complained that the presidency was an office of “splendid misery,” which “brings nothing but increasing drudgery & daily loss of friends.”

Add to that the fact that he had more than a little bit of the recluse in him. Twice he withdrew entirely from public life, first in the 1780s, after a disappointing term as governor of Virginia, then at the conclusion of his presidency, when he left Washington disgusted and exhausted, anxious to be rid of the place. As he wrote a friend, “Never did a prisoner, released from his chains, feel such relief as I shall on shaking off the shackles of power.” Never was he happier than when ensconced in his Monticello retreat, his “portico facing the wilderness” that he loved and found renewal in. This was a most complicated man.

A MAN OF MANY LETTERS

At bottom, I think Jefferson is best understood as a man of letters. Literally. Jefferson wrote almost 20,000 letters in his lifetime, and it is in these letters that he seems to have felt freest and most fully himself. Although he complained to John Adams that he suffered “under the persecution of letters,” the opposite seems to have been the case. This was a man who lived much of his life inside his own head, and it is in these letters that he comes most fully alive for us. He seems to have needed the buffer of letters interposed between himself and the world; but with that buffer in place, the otherwise awkward and taciturn Jefferson became more open, wonderfully expressive and responsive to his correspondents. As Kidd observes, he was probably too open and too expressive in his correspondence, more imprudent than his cautious friend Madison, and some of the contradictions between and among his letters are particularly attributable to the enthusiasm with which he approached the task of letter writing. In this aspect, Jefferson can seem especially appealing.

The correspondence is always very personal, very much directed toward the particular correspondent. Which is one reason why his thinking was different in different places. It was in his letters to Maria Cosway, for example, that we glimpse his passionate nature and the struggles between head and heart that preoccupied much of his inner life. It is in his letters to his nephew Peter Carr that we see his thoughts as a preceptor and wise guide to the world’s ways. And it was in his magnificent correspondence with his old rival John Adams, a dialogue that spanned 50 years until their deaths in 1826, that Jefferson most fully explored the deeper meaning of the American experiment. He was constantly using his correspondence to organize and sharpen his thinking, and it is there that we see him most fully and vividly.

In any event, it is for his ideas, above all else, that we honor Jefferson, and for the cause of human freedom and human dignity that he so eloquently championed. His failings may weigh against the man, but not against the cause for which he labored so mightily. That should be a lesson to us today. Like Jefferson, we are carriers of meanings far larger than we know, meanings whose full realization cannot be achieved in our lifetime, or even be fully understood by us, but which we are nevertheless charged to carry forward as faithfully as we can.

But unlike Jefferson, we have the benefit of being able to stand on his shoulders, with his words to direct and inspire us. “We knew” about Jefferson’s faults, said the late representative and civil rights leader John Lewis. “But we didn’t put the emphasis there. We put the emphasis on what he wrote in the Declaration. … His words were so powerful. His words became the blueprint, the guideline for us to follow. From those words you have the fountain.”

It is the same fountain that today nourishes our lives and shows no sign of running dry. Today is a good day to drink from it anew. And, if you like, also to say, “We are all Jeffersonians.” Because, in fact, we are.