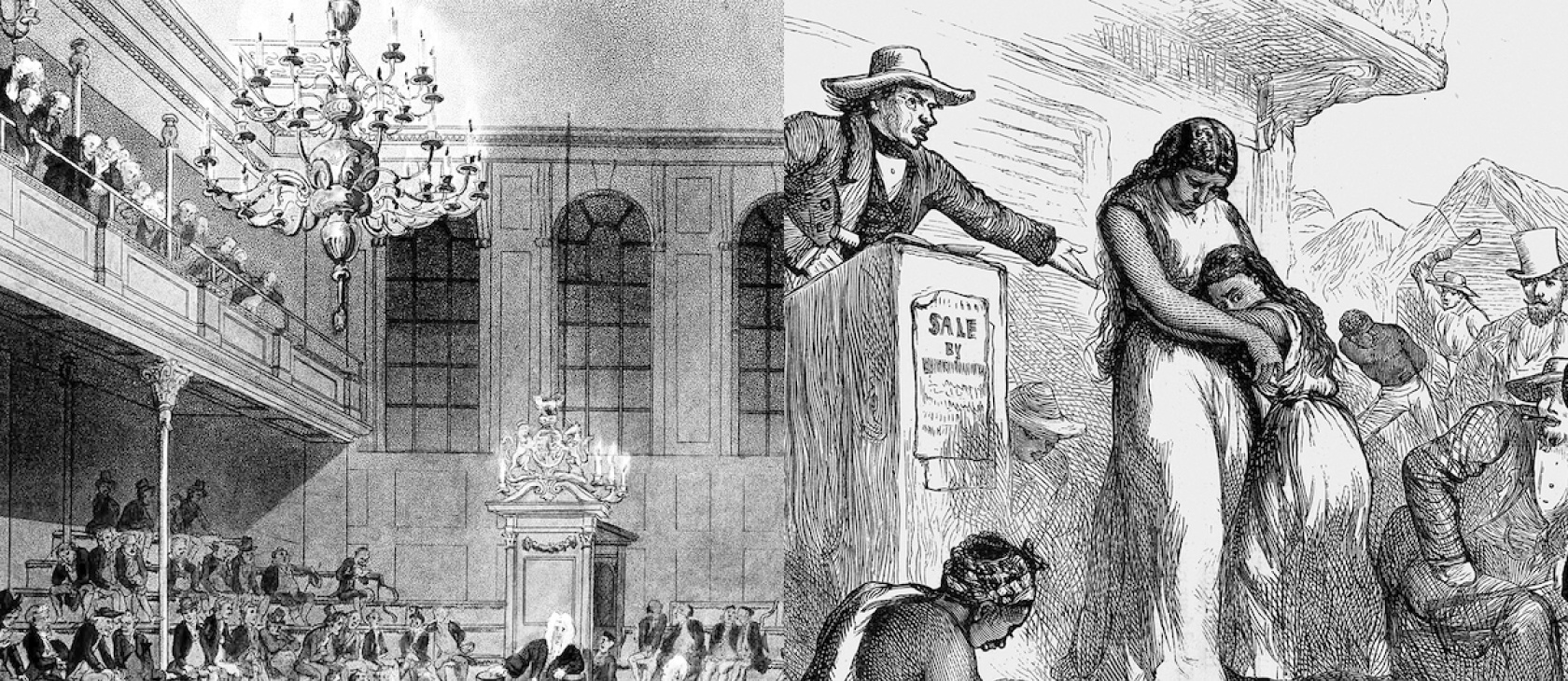

It may be the most decisive and complete victory in any moral argument in human history. European and North American elites had, for centuries, deliberately ignored the ethics of the Atlantic slave trade, or justified it as a regrettable necessity, or simply accepted it as a vast fact of life that could not be wished away. Suddenly, in the 1780s, a previously eccentric and extreme view—that the trade ought to be abolished—won a mass following in both Britain and the newly independent United States. In 1807 both countries legislated to abolish the trade, and over the following decades the other European imperial powers were cajoled or coerced into following suit.

We prefer black and white to shades of gray, especially when it comes to our heroes. But the end of the slave trade, and of slavery itself, involved all manner of compromise and casts of mind we would find repugnant today. But given the results, who are we to judge? Perhaps we have much to learn.

The righteousness of this cause is now so utterly self-evident that the subject is hard to see clearly. We now remember the Atlantic slave trade as an exceptional horror, standing alongside the 20th-century genocides as one of the greatest crimes in human history. Surely only a monster would defend, excuse, or minimize it; surely those who brought it to an end must be heroes.

But while stories populated by monsters and heroes are very comforting, they are not good history. We use such stories to sing ourselves songs we already know and love, but we don’t learn anything from them, and we end up reducing people in the past to bit parts in dramas we have scripted for them. We don’t need to abandon our own hard-won moral insights to recognize that our 18th-century forebears didn’t see this issue in quite the way we do.

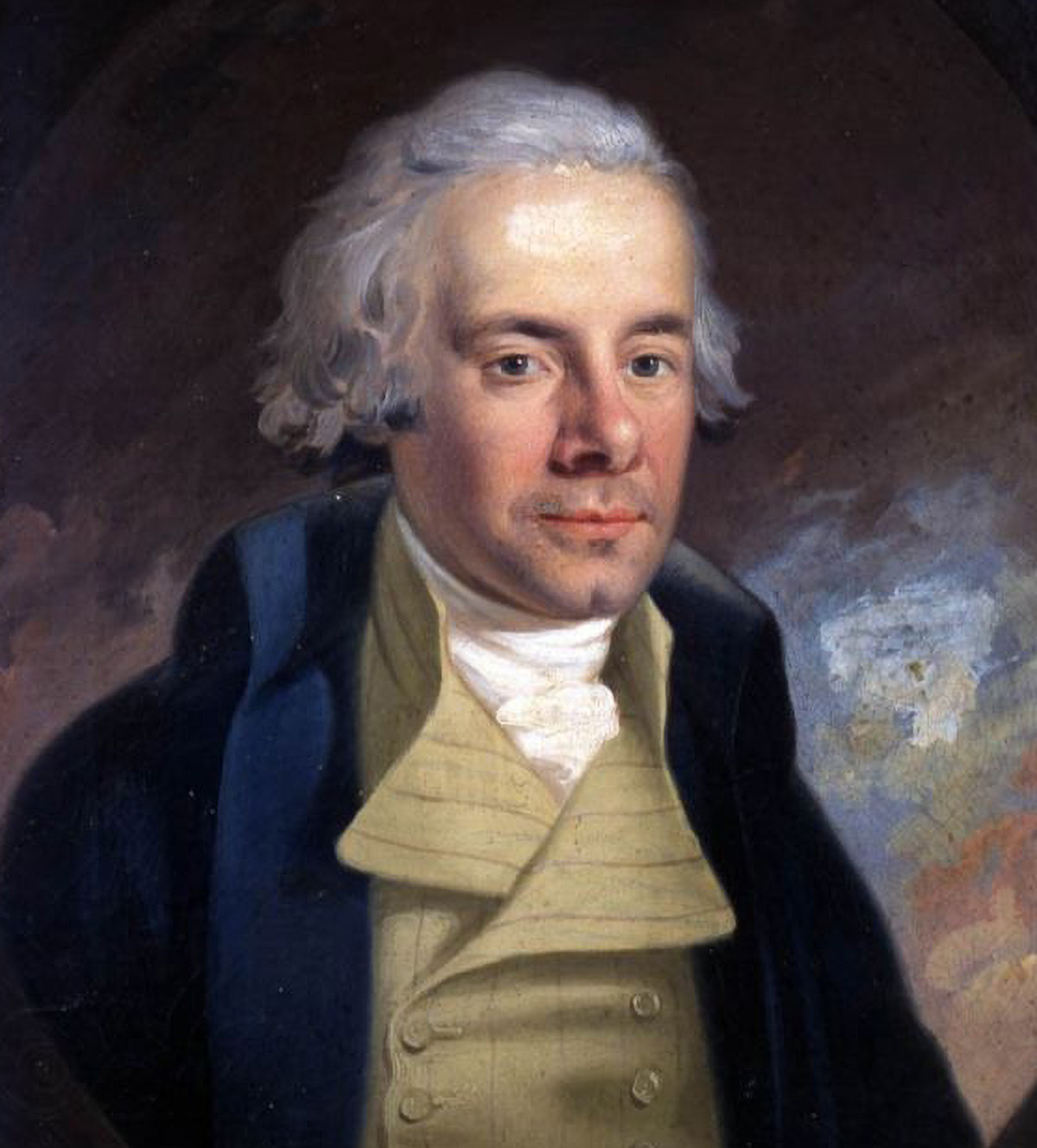

So, what are we to make of the traditional heroes of slave-trade abolition? William Wilberforce, the English evangelical politician and bon vivant, is the best known of the so-called Clapham Sect of aristocratic evangelicals who campaigned for a series of moral reforms. Wilberforce took the demand for slave-trade abolition into Parliament in the 1780s, kept the cause stubbornly alive during the hard years of the 1790s, and finally spotted and seized the moment in 1807, when the British establishment could be persuaded to do the right thing. His moral revulsion at the slave trade was unmistakable. But this is also the man who wrote, in the very year the trade was abolished, that slavery itself ought to continue for a while yet. “Our poor degraded Negro Slaves are as yet incapable” of enjoying freedom, he reckoned: “to grant it to them immediately, would be to insure not only their masters’ ruin, but their own.” Hero—or monster?

Naturally, what we do with people like Wilberforce is to conscript them as cannon fodder in the culture wars. One side finds that a white evangelical who campaigned against slavery provides very welcome political cover and essentializes his admirable qualities while downplaying, contextualizing, and excusing his shortcomings. The other side detects a classic white-savior narrative, in which helpless black people are rescued by the intervention of a kindly white man, reduced to nonspeaking parts in their own story, and expected to be grateful for the judicious recommendation that they endure a few more decades’ enslavement.

If you want to make one or other of those arguments, feel free to stop reading now and to fire up your phone. But the story of how and why some white Europeans and Americans came to this moral awakening; of why this happened when it did, and not before; and why it was real, but partial—this story has more to offer us than heroes and monsters. As our own age wrestles with moral dilemmas that might seem divisive and intractable to us but intolerably clear to our descendants, we could have something to learn from them.

Deliverance from “Pagan Darkness”

Why did Wilberforce and his friends in the Clapham Sect oppose the slave trade? It is hard even for us to ask the question, as the evil they were opposing seems so self-evident. Violently abducting millions of people from their homes; shipping them across the Atlantic in conditions so nightmarish that a sixth or more of them died en route; condemning the survivors and their descendants to a perpetual and irredeemable enslavement in which they were generally denied the most basic of human dignities. Surely we do not need to explain why any human being should be appalled by such things?

Yet people generally prefer not to see horrors. Before the sudden awakening of the 1780s, most of the good Christian people of Europe and the Americas had been at least dimly aware of the slave trade for centuries, and few of them had done much about it. From the start there was a widespread sense that there was something not entirely right about the whole business. In a series of British colonies, from Providence Island in the Caribbean to Georgia on the American mainland, the first founders tried to exclude slavery. But, repeatedly, they failed. Running a successful New World colony in the 17th and 18th centuries without slavery was like running a modern economy without oil: conceivable, desirable, but no one has actually managed to do it.

Atlantic slavery had plenty of white critics, but their criticisms don’t line up neatly with modern perspectives. True, a few voices always insisted that enslavement was no more than institutionalized kidnap and murder. That point was made forcefully by the Massachusetts judge Samuel Sewall in a seminal anti-slavery tract in 1700. Yet Sewall also argued that filling New England with black pagans was undesirable. Even if they were set free, he lamented, “They can seldom use their freedom well,” and “there is such a disparity in their Conditions, Colour & Hair, that they can never embody with us, and grow up into orderly Families.” Instead, they would “remain in our Body Politic as a kind of extravasate Blood.” Others worried that slavery would, as one opponent of allowing slavery in Georgia argued, “be very Mischievous … to the poor white labouring people.” It is, after all, hard to compete with unpaid laborers who can literally be worked to death. The most widely voiced ethical criticism of slavery was that, since slaves were unable to solemnize marriages, slaveholders were (as Sewall put it) tempted “to connive at the Fornication of their Slaves.” Consciences that could swallow enslavement itself revolted at the irregular liaisons it brought in its wake.

Atlantic slavery had plenty of white critics, but their criticisms don’t line up neatly with modern perspectives.

As that implies, the principal Christian critique of slavery before the 1780s was not of the institution itself, but its spiritual effects. When Bishop Gibson of London wrote an open letter to slaveholders in the British Empire in 1727, his subject was “delivering those poor Creatures from the Pagan Darkness and Superstition in which they were bred,” not setting them free. In fact, like many others, he insisted at length that a Christian slave would be a contented, obedient, honest, and hard-working slave. Ideally, the whole distasteful business of shipping Africans across the ocean could be redeemed by paternalistic care for their bodies and Christian ministry to their souls.

The hollowness of Gibson’s call was exposed by a Caribbean Anglican priest, Robert Robertson, who in a brutally honest rebuttal explained that a reformed or Christianized slave system was impossible. Robertson robustly defended enslaving Africans, whom he despised for their “Dulness, Defects, Corruptions, and Perverseness.” But he would have none of Gibson’s fairy tales. These, he reminded his readers, were people ripped from their homes, nearly half of whom died in their first year in the Caribbean; the rest were (and, he insisted, must be) kept in conditions of squalor and degradation. If people in Europe truly knew “the Nature and Circumstances of this abstruse uncouth Trade … the Millions of Lives it destroys,” they might, he admitted, want to abolish it—but such a thing was impossible. If one country did so, the others would swarm in like vultures. He saved his contempt, however, for the do-gooders in England who deluded themselves that slavery could “have Christianity grafted onto it.” “Any Man … who knows what Christianity is, and what this Slavery is,” would know that a “Christian-Slave” is as impossible “as God-Mammon, or Christ-Belial.”

Robertson truly was a monster, but he was at least a clear-sighted one, able to name the evils around him even as he refused to oppose them; few of us can say as much. And he stands as a terrible witness against his generation. As early as 1730, the brute facts of the slave trade were published openly for whoever wanted to see them. It is true that most Euro-American whites remained blind to those facts for another 50 years, but that is because—like most of us when confronted with dreadful and intractable evils—they chose not to see.

African Agency and Revolutionary Fervor

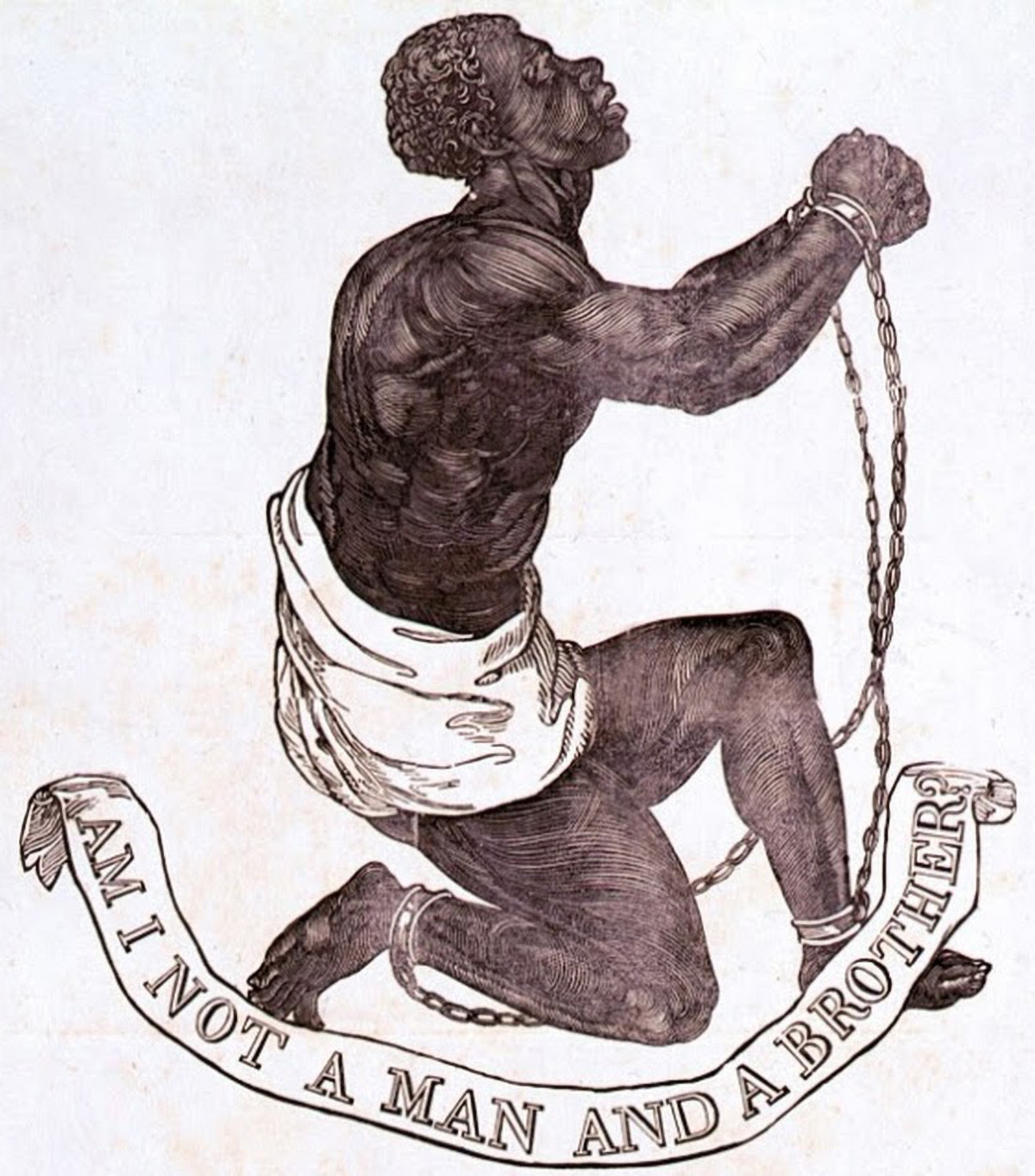

And yet, half a century later, Wilberforce and his allies were able to mount a campaign to abolish the slave trade, which, in its first flush in the late 1780s, secured signatures for a petition from over a tenth of Britain’s entire population, and a thumping majority in the House of Commons in 1792. The bill was then blocked in the House of Lords, and the political winds turned against it, but 15 years later it was finally enacted. It is an exemplary case of transformative moral and political change.

The cause did not properly come to Wilberforce’s attention until 1787, although other members of the “Clapham Sect,” notably Granville Sharp, were some of the way ahead of him. Abolitionism had begun in a few minority ghettos—Quakers, some Methodists, a handful of freethinkers. Some lawyers took up the cause, and while the 1772 ruling that England was “free soil” freed but one solitary slave, James Somerset, it also gave notice that the English establishment’s consciences might be stirring in their sleep.

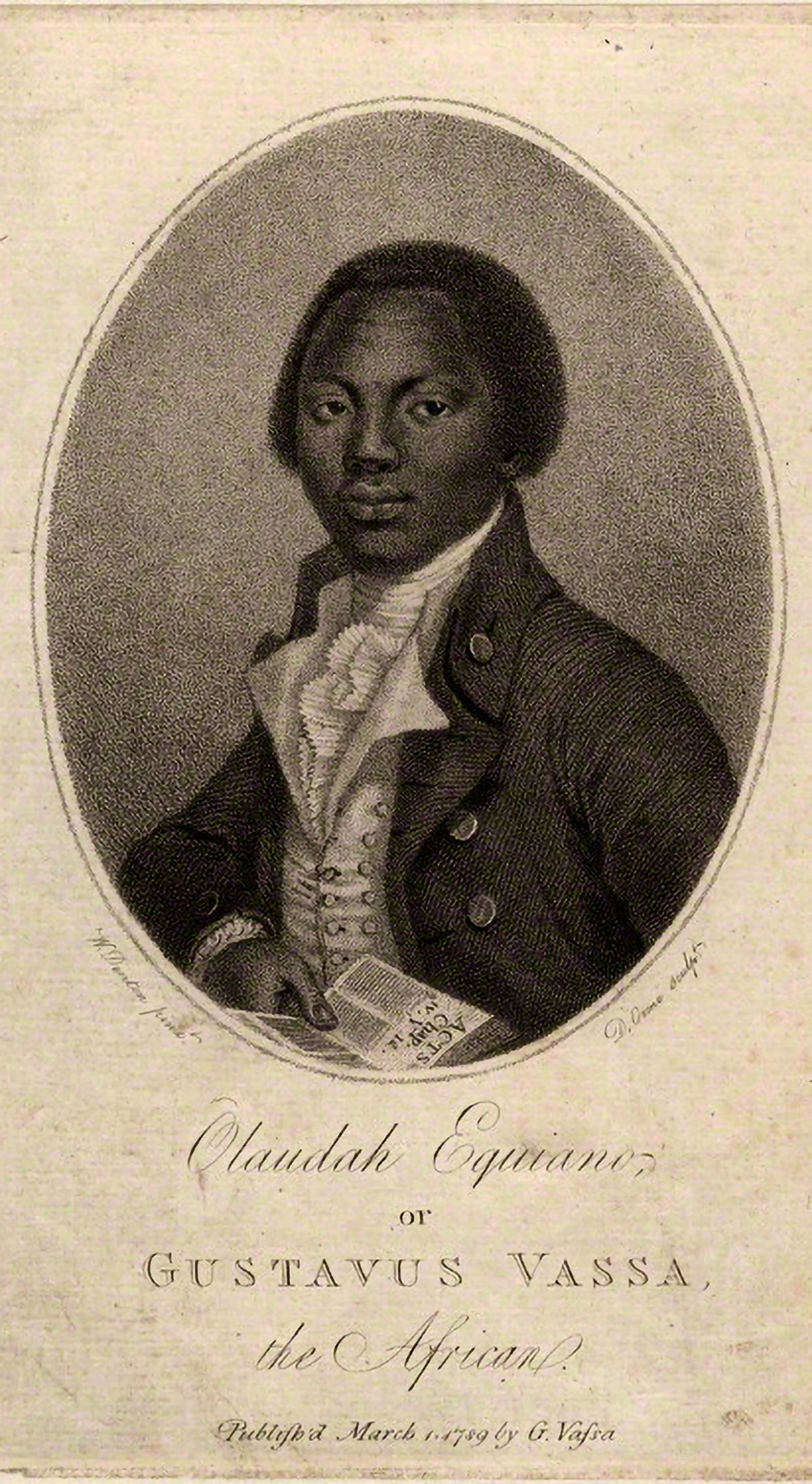

A vital part in awakening them was played by Africans themselves, a tiny but highly visible minority in English society. The most famous African voice raised against the slave trade was that of Olaudah Equiano, whose autobiographical Interesting Narrative (1789) delivered many times over on its title’s modest promise: After being kidnapped and enslaved aboard a naval ship, Equiano was freed, reenslaved and shipped to the West Indies; he bought his freedom and traveled as far as Central America and the Arctic before finally settling in London. His gripping adventures and his disarming literary style made the injustice of what he had endured inescapable.

A less heroic but more telling case was that of Philip Quaque, the first African to be ordained in the Church of England, having been shipped to London for education as a child. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel sent him to his homeland as a missionary, based in a slave-trading fortress. It was an impossible role. “The vicious practice of purchasing flesh and blood like oxen,” Quaque told American friends, made Christian ministry futile. Quite apart from what it did to “my poor abject Countrymen … whom you without the Bowels of Christian Love and Pity, hold in cruel Bondage,” it corrupted the morals of the white traders so profoundly that he could not minister to them either. When he described the obstacles his mission faced for his correspondents in London, he was blunt: “principally the horrid Slave Trade.” As Robertson had observed a generation earlier: Working within, ameliorating, or reforming this system was not an option.

That realization was slowly gathering pace across the middle of the century, as wishful thinking and self-deception were worn down by bitter experience. But what truly brought the matter to the fore was the American Revolution, which created abolitionism as we know it, in three quite distinct ways.

First, most famously but perhaps least importantly, its ideals of liberty were obviously applicable to slavery. Notoriously, many American Patriots refused to draw that conclusion. But it is true that the abolition of slavery in the northern states, and the clause in the 1787 Constitution that (eventually) empowered the federal government to ban the foreign slave trade, could not have happened without the Revolution as an ideological accelerant. It is no coincidence that the briefly independent republic of Vermont had, in 1777, the world’s first constitution prohibiting slavery. True, the abolitionist wave that swept across the North was too weak to reach south of Philadelphia. But had Britain and the colonies managed to resolve their differences peacefully, American abolitionism would have been feeble indeed.

More importantly, American independence transformed the question of slavery in what remained of the British Empire. As long as there were American colonies to be placated, no British government would risk irritating slaveholders. But now the South’s slaveholders were someone else’s problem. The handful of planters on the Caribbean islands, vastly outnumbered by the enslaved population, were in no position to dictate terms to London. The slaveholding lobby in the British Parliament was suddenly flimsy. A united British-American empire would not, could not, have abolished the slave trade.

Most of all, American independence provided Britain with a motive as well as an opportunity. The shattering, unimaginable defeat in the New World felt like divine judgment for a national sin. But what sin? At the start of the American war, a few siren voices, such as John Wesley’s, had warned that God would punish Britain’s empire of slavery with defeat. That prospect seemed laughably unlikely, but in retrospect perhaps they were right. A scandal like the Zongcase—in which 131 enslaved men and women were deliberately drowned in pursuit of a fraudulent insurance claim—would not have had the same cut-through to British readers had it not come to court in 1783, the year that a stunned Britain was forced to accept that the American war was lost. It was also the year the first really commercially successful anti-slavery pamphlet, The Case of our Fellow-Creatures, the Oppressed Africans, was published. It cited the Bible’s warning that “the Righteous Judge of the whole earth chastiseth nations for their sins.”

It was this live fear of divine judgment that gave urgency to abolitionism, which began to seem a matter of immediate self-defense. Every hurricane in the West Indies now looked like a portent of doom. Bristol and Liverpool would be judged like Tyre and Sidon before them. Terrible warnings of national guilt and imminent judgment were a mainstay of Wilberforce’s speechmaking, the more so as, from 1792, Britain embarked on a new, existential war with revolutionary France. If God was using the atheist revolutionaries to chastise his sinful people in Britain, what sin could be greater than the slave trade?

Late to the abolitionist party as they were, Wilberforce and his friends brought something indispensable to it: respectability. The “Clapham Sect” is a later nickname for his south London coterie: Contemporaries called them “the saints,” with a note of mockery. But these were no pious eccentrics. The group included half a dozen MPs, prominent Anglican clergymen, at least one leading lawyer, and, later, the governor-general of Bengal. They had friends everywhere and they knew how to use them. Wilberforce’s own saintliness is undoubted, but so is his appetite for and ease with high politics. He was the kind of evangelical whose diary reveals him solemnly pledging, as a pious discipline, never to drink more than six glasses of wine a day. He believed that a Christian should combine seriousness with sociability and was known to be scintillating company. He tried hard to restrain his knack for biting sarcasm, not with total success.

The Claphamites’ antislavery campaign is a master class in the political power of high principle, tactical cunning, and bloody-minded persistence. Wilberforce in particular was one of history’s great badgerers. One ally described him as “the most damned intractable fellow with whom I ever had to deal.” Grinding the cause forward inch by inch, they accepted tactical victories, allies of convenience, and fair-weather friends. And in 1807, when the moral, commercial, military, and party-political stars were all, for a moment, aligned, they spotted their opportunity and pounced.

Freeing Bodies to Save Souls

Abolishing the British slave trade was never an end in itself for Wilberforce and his friends. It was both a stepping stone to greater aims and part of a wider constellation of causes, and unless we understand that dual context, we will not understand their achievements.

American independence transformed the question of slavery in what remained of the British Empire.

Naturally those greater aims included suppressing other nations’ slave trading. If abolitionism sprouted from a British defeat in the American Revolution, it flowered thanks to a British victory. After the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, Britain could use its mastery over the Atlantic to bribe and bully other slave-trading powers, one by one, into compliance. But while we might imagine slave-trade abolition would be a springboard for abolishing slavery outright, most of Wilberforce’s allies shared his hesitancy. This was not a modern human rights campaign, freeing the enslaved to be the sovereign individuals of liberalism. The point was to free them to be what God had created them to be, which was not simply a matter of unlocking shackles.

Quaque’s observation—that slavery was the greatest obstacle to saving Africans’ souls—was at the heart of the abolitionist cause. Bishop Gibson’s generation had tried to bring Africans to Christ by working with and through the slave system. The effort was abandoned, not because it was immoral, but because it wasn’t working. By the 1780s, the consensus was that a Christian culture could not be built on slave plantations as long as a majority of the enslaved were adult captives: too old to be formed in Christianity and unlikely ever to have a solid command of English. But—so the argument went—if slaveholders were forced to work with the people they already had rather than importing more, they would learn to be more careful with human lives. In addition, the enslaved children they raised on their plantations could be made both civilized and Christian, inheriting a spiritual freedom that (it was axiomatic) mattered far more than the bodily kind.

We can see this most clearly when we look at the Clapham saints’ abolitionism in the context of their other moral projects. They defended the worldly interests of the helpless but did so for spiritual reasons. Their campaigns do not quite mesh with modern moral priorities. Missionary work was a key concern: Several of them were founding members of the British and Foreign Bible Society. The troubled resettlement colony of Sierra Leone, founded as an African refuge for former slaves, was very much a Clapham project, and one of the saints, Zachary Macaulay, was its first governor. Closer to home, reforming the exemplary cruelties of English criminal justice was a persistent concern; but so too was the work of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, founded by Wilberforce in 1787, dedicated to opposing such evils as Sabbath breaking, profanity, the “publication of blasphemous, licentious and obscene books and prints,” gambling, prostitution, and cruelty to animals. As those paternalistic priorities might imply, civil liberties and freedom of speech were not among their priorities: Wilberforce strongly supported the crackdown on political radicalism in the 1790s enforced by his good friend William Pitt, Britain’s prime minister. Hannah More, the most prominent woman among the Claphamites, was a passionate opponent of the slave trade and a supporter of girls’ education, but she vehemently opposed Mary Wollstonecraft’s feminism. When the Royal Society of Literature naively made her an honorary member, she refused, believing that no woman should be so elected. She insisted that the schools for poor girls she founded would teach them to read, not to write. The purpose of education was to inculcate godliness—a concern she shared with another Claphamite, Henry Thornton, a pioneer of schooling for the deaf.

As to Wilberforce himself, he made clear that his political life was dominated by two great moral causes: the slave trade and Christian missions in India, which the British East India Company regarded as bad for business and consistently blocked. “Next to the Slave Trade,” Wilberforce wrote in 1806, “I have long thought our making no effort to introduce the Blessings of religious and moral improvement among our subjects in the East, the greatest of our National crimes.” A door had finally opened for this cause: another of the Clapham saints, Charles Grant, had been elected as the East India Company’s chairman the previous year. When the Company’s charter was up for renewal in Parliament in 1813, Wilberforce and Grant spearheaded a formidable campaign that resulted not only in much increased scope for Christian missionaries in India but also for the Company’s acceptance of “religious and moral improvement” as one of its objectives.

By “moral improvement,” the Claphamites meant specific practices that revolted their Christian consciences—for example, in India, the caste system, infanticide, and above all sati, the occasional Hindu practice of killing widows by burning or burial, which in pious British eyes became a symbol of all that was barbaric about India. It was because of practices such as these that Wilberforce argued in 1813 that Hinduism was “one grand abomination,” a religion that was “mean, licentious and cruel,” whereas Christianity was “sublime, pure and beneficent.” Hence “religious and moral improvement” really were one thing. Indians needed to be freed from a spiritual captivity just as cruel as the bodily captivity of enslaved Africans, and in both cases it was Christianity that would do it.

From our 21st-century vantage point, there are two obvious perspectives available on this attitude. We can admire its moral clarity, its readiness to speak out against oppression regardless of cultural context or commercial interest, and its enthusiasm to give the greatest gifts of which it knew to the people who needed them most. Or we can lament its (to us) jaw-dropping lack of cultural and intellectual humility, its conviction that barbaric peoples needed to be saved from who they were, and its unquestioned imperial assumption that it was the right and the responsibility of the British to do it. But, mercifully, it is not our responsibility to sit in judgment over the consciences of the dead. We can simply admit that both perspectives are true.

Eccentric Causes Can Be Won

What do these far-off struggles have to say to those pursuing urgent moral causes in our own times? There are some practical encouragements and warnings. Eccentric, niche causes, far outside the consensus, can triumph in the end, with patience, persistence, and cunning. Moments can be seized: During times of flux, ideas that had once seemed outlandish can become truisms with startling speed. Entrenched views—such as the belief that slavery could be Christianized—can last a long time in defiance of evidence and of experience, but not forever; even the most wishful of thinkers tire of beating their heads against brick walls in the end. Clearly defined and achievable intermediate aims are much more likely to pave the way to eventual success than simply striking out heroically for the horizon. Broad coalitions can achieve things that narrow campaign groups cannot, and purity tests only serve a campaign’s opponents. You do not need to agree with someone’s views on all subjects, or even to respect their motives, to ally with them. And, in particular, insiders and establishment figures, natives of the structures of power, have an invaluable part to play. Revolutionary rhetoric may make people feel good, but those who know how to work patiently and stubbornly through systems and institutions can actually get things done.

If, of course, getting things done is your goal. Then and now, many campaigners were more concerned to whip up politically useful outrage, or to burnish their own sense of their purity, than to get into the messy business of compromise that is the usual route to substantive change. We might, for example, look at the contrasting fortunes of the actual abolition of slavery in the British Empire and in the United States.

Eccentric, niche causes, far outside the consensus, can triumph in the end, with patience, persistence, and cunning.

Slavery in the British Empire was ended through a very unheroic political deal, the centerpiece of which was the payment of handsome compensation to slaveholders for the loss of their “property.” This, in fact, was the case in every Atlantic jurisdiction where slavery was abolished, bar one. While the perpetrators of the crime of slavery were thus bought off, the victims were, naturally, left uncompensated. The injustice of these legalized ransoms was obvious even at the time. Needless to say, they have never been systematically repaid, nor have the enslaved or their descendants ever received systematic reparation.

The one exception was of course the United States, where the price to end slavery was paid in blood, and where a victorious Union at last simply imposed the legal principle that human beings are not property. It is a far purer, more righteous solution. Yet was it better? It is not simply that it cost 30 more years of servitude and half a million lives. The legacy of slavery also continues to poison the United States more deeply than any other Atlantic-facing society. Would that be different if the former slaveholders had been compensated for their “loss” instead of being defeated in war? To have offered them such a deal would have been morally repugnant; nor, to be clear, would they have accepted it. But would it have been a price worth paying?

Wilberforce would have paid it. Our consciences revolt at the thought. Perhaps it doesn’t matter much anymore—what’s done is done. But in our modern struggles, whatever they may be, there may also be occasions where the grand moral satisfaction of simply defeating our enemies should be weighed up against the prudence of swallowing our principles and buying their complicity. After all, if we are anything like the abolitionists of the 1780s—whose shoes few of us would be worthy to unloose—we ourselves are already far more morally compromised than we think. Giving our “enemies” enough to win their consent may not feel good, but it can actually advance the cause. It may even make it easier for us all to live together afterward.