Among the many wonders of user-created content on the internet, a person of angelic patience, able to separate the wheat from the chaff, can acquire an amateur education in most anything. Recently, I’ve been delving into music theory. I’m no musicologist, but I play a little piano and guitar, and I wanted to expand my understanding for creative purposes. The more I understand, the more I can do with my own music.

The debate over the relation of God to his creation, of the divine to the human, rages on. But one seventh-century saint may offer a way out of the theological impasse. With a little help from Handel … and Bon Jovi.

By Jordan Daniel Wood

(Notre Dame Press, 2022)

I’ve discovered at least three kinds of song analysis videos on YouTube: The first is the “reaction” video, where a person records his first listen to a popular song. These tend to be primarily emotional, but watching someone hear a song I know and love for the first time can bring a freshness to it. In the second type, some creators add an intellectual layer by commenting on the lyrics or instrumentation. In this genre, to give an example, I find that fans of hip-hop, in which the words are front and center, tend to offer exceptional insight into folk and rock lyrics, sometimes for songs I’ve heard a hundred times. The third kind of song analysis comes from expert music theorists and producers, for whom the songs are not new at all. Instead, they offer a breakdown of songs track by track, isolating drums, bass, guitar, and vocals, analyzing chord progressions, key changes, and time signatures.

Thus, if you want to try this at home, consider “Livin’ on a Prayer” by Bon Jovi. You can find videos of people simply experiencing this song for the first time and offering their raw reactions. Other videos periodically stop to offer commentary on the lyrics or the feel of the song. Lastly, you might find a video or two that breaks down the true artistry of this ’80s rock anthem, pointing out subtle background instrumentation or analyzing how the song’s famous key change actually jumps a minor third, and that the transition preceding it drops a beat with a single bar of 3/4 time. Instead of just listening to a song that resonates with you, you can increase your appreciation by listening as others share their experience and expertise.

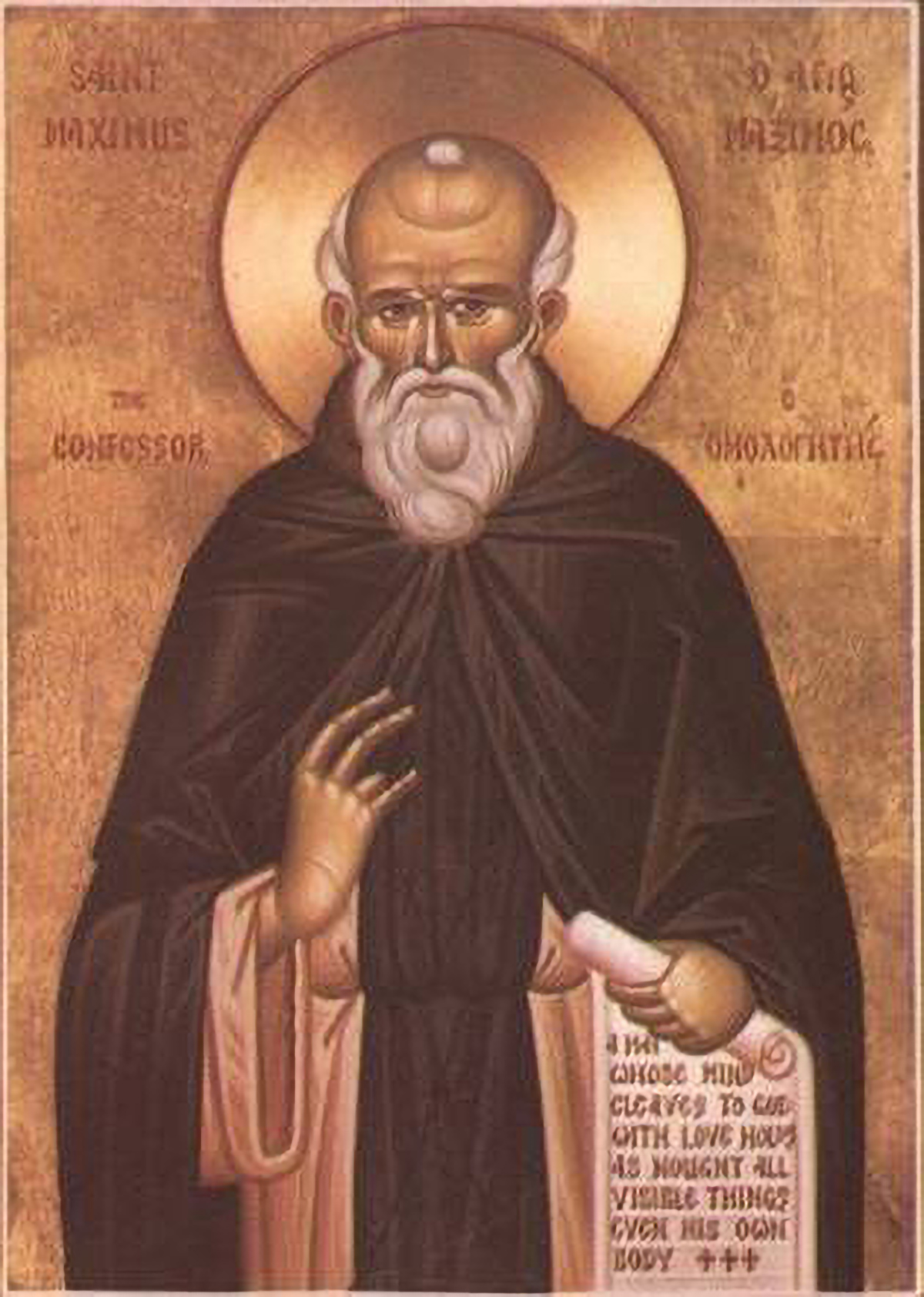

This may seem unique to the 21st century, but as the Scripture teaches, “There is nothing new under the sun” (Eccl. 1:9). Sure, song analysis videos didn’t exist in the seventh century, but theological commentaries by this time had cemented their place in cultural creation, with the highest possible stakes. In The Whole Mystery of Christ: Creation as Incarnation in Maximus Confessor, Jordan Daniel Wood, adjunct professor of theology at Saint Louis University, offers his analysis of the Byzantine saint, theologian, and martyr Maximus the Confessor. Tortured and rejected in his own time, Maximus would finally be vindicated (though not in name) at the Sixth Ecumenical Council and become the focus of philosophical retrieval only in the past few decades. Much of Maximus’ writing, including the passage that is key to Wood’s thesis, comes from his commentary on difficult passages in the homilies of the fourth-century patriarch of Constantinople, St. Gregory the Theologian. And Gregory’s homilies, in turn, consist of his reflections on the Gospel through scriptural commentary, dogmatic disputes, or liturgical feast days. So, to recap: Wood’s book is a commentary on a commentary on a commentary on the Gospel. And this review (as if that weren’t complicated enough) is like an analysis video of the second or third type above. It’s a first reaction to The Whole Mystery of Christ but from someone with some relevant knowledge and expertise.

Now, readers could be forgiven for asking, “Why would anyone need that?” But I’ve already made that case. Just as I’ve learned so much from commentators today about my favorite songs, so also if you love the Gospel, the promise of a book like this is that through reading it you might love Jesus Christ even more, in ways you couldn’t before have imagined.

Wood, for example, teases out profound implications from a single sentence of Maximus: “The Word of God, very God, wills that the mystery of his incarnation be actualized always and in all things.” Whether other scholars will fully subscribe to Wood’s tightly reasoned argument, that the logic of creation and Christ’s incarnation is the same, nothing can detract from the intellectual achievement of this book, grappling with a difficult and ancient text and spanning the entire range of metaphysics (philosophical reflection on the nature of reality) and soteriology (theological study of the nature of salvation). It has, at least, helped me better grasp Maximus’ insights into the mystery of Christ. Saint Louis University would be wise to offer this adjunct professor a permanent position before another institution swoops in and steals him away.

Parsing the Word

In order to understand Wood’s claim about Maximus’ theology, I here offer a brief layperson’s review of some important theological concepts. Hopefully nothing will be lost in translation, but one always risks doing that when trying to communicate academic work into everyday idioms. Not to worry, though. All I need to do is explain the Trinity and Incarnation. Easy, right?

The big controversy in the fourth century, Gregory the Theologian’s day, was how to relate the one to the many in the Holy Trinity. The solution goes something like this: What is the Holy Trinity? God. Who is the Holy Trinity? Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The “what” is nature, essence, or substance. The “who” is person or subsistence.

The church fathers apply this to all persons and natures. Thus, one of their most common examples is Peter, James, and John. They aren’t the Holy Trinity. They are separated by time and physical distance and may act in conflict or discord. But they are a human trinity. How many natures do they have? One. How many persons are they? Three.

This differs from pagan polytheism in which gods like Zeus, Artemis, Apollo, and Poseidon only have similarnatures. This differs from Jewish monotheism, wherein “God” refers to both nature and person, and thus the number of each is one. Rather, Christians are Trinitarian monotheists, believing in one God but three divine Persons who always will and act as one.

Nothing can detract from the intellectual achievement of this book, grappling with a difficult and ancient text and spanning the entire range of metaphysics and soteriology.

Next: the Incarnation. Just as the Council of Constantinople in 381 resolved the disputes over the Trinity, conflict continued over the mystery of Christ as both God and human. Again, it is a problem of the one and the many. Christ’s divinity doesn’t swallow up his humanity, nor does the divine Word simply accompany a man named Jesus. Rather, “the Word became flesh” (John 1:14). In this case, the “what” has two answers: fully God and fully human. The “who” has just one answer: the Son of God, Jesus Christ. The Council of Chalcedon in 451 offered the definitive formulation of the nature of this reality: Jesus Christ is both God and human “in two natures,” united in one person “unconfusedly, immutably, indivisibly, [and] inseparably.” While it took centuries to work out the details—even into the seventh century and Maximus’ work—the most perfect summary comes, again, from Gregory the Theologian: “That which He has not assumed He has not healed; but that which is united to His Godhead is also saved,” or literally “deified.”

So, in the Word of God, God himself, utterly unlike creation—immaterial, immutable, impassible, and so on—became part of creation, the man Jesus Christ. Wood points out that for Maximus it is precisely the radical dissimilarity between Creator and creation that makes this possible: the Incarnation of the Word takes nothing away from his divinity while entirely preserving the fullness of humanity, since created and uncreated nature share nothing in common that could come into conflict with one another. At the same time, the only way this union could come about “unconfusedly, immutably, indivisibly, [and] inseparably” is if the locus of union is the Person of Jesus Christ—a concrete “who,” not an abstract “what.” If readers can begin to grasp that, they can start to see some insights Wood’s work offers us today.

God’s Symphony

One of the many controversies in Maximus’ day had to do with the nature of creation. Origen of Alexandria, the third-century church father, gave the Church a large amount of its theological vocabulary. Thus, we all owe him a debt. Unfortunately, so does nearly every heretic after his time as well. Origen borrowed a bit too much from the Platonism and Gnosticism of his day and theorized that souls originally emanated from God but became dissatisfied with him, and that God only created the material world as a sort of safety net to catch them in their metaphysical fall. Ultimately, they would once again be subsumed into God at the end of all things. Origen’s influence became such a big problem that the Fifth Ecumenical Council in 553 posthumously excommunicated him and his controversial teachings.

Thus, when Maximus writes, “The Word of God, very God, wills that the mystery of his incarnation be actualized always and in all things,” he partly aims to refute Origen’s heretical teachings on creation, salvation, and the end times. Maximus does this through what has become a hallmark of his thought: In God’s creation of the world through the Word (logos), he patterned each and every element of creation after their own unique words (logoi), present within the Word from all eternity. God created the world through speech (Gen. 1), and “The heavens declare the glory of God…. And their words [have gone out] to the end of the world” (Ps. 19:1, 4).

Once again, music can be our metaphor. Consider George Frideric Handel’s Messiah. Handel shares almost nothing in common with his famous oratorio; he’s a man, not an arrangement of musical notes and words, nor the performance thereof. And yet, if you happen to hear a portion of it, you might ask a friend, “Is this Handel?” Why? Because while remaining utterly unlike his music in terms of “what” he is, there is nevertheless something of Handel inhis Messiah, without reducing the one to the other. Similarly, without falling into pantheism, Maximus claims that through the words of creation, the Word of God himself is in all creation. Creation is God’s symphony; Christ, our composer.

Moreover, the Holy Trinity created humanity “in Our image, according to Our likeness” (Gen. 1:26), shaping our body from the earth and breathing in our spirit from heaven (Gen. 2:7). Human nature is a microcosm of all creation. To the extent that we are uniquely created in the image of God, it could not be otherwise. The many words of each element of creation are grounded in the Word of God through whom “All things were made” (John 1:3). Our vocation, according to Maximus, is to unite all divisions of nature—heaven and earth, male and female, and so on—both within us and to God.

Alas, no sooner than we were created, we—and all creation with us—fell away through sin from those words by which we were created. Thus, in the Incarnation and the Cross, says Wood, “God suffers in and with and as us because his personhood is infinite, and so he can, and his will is infinite love, so he wants to.” God does what we could not so that we can do what he did. Or as St. Athanasius the Great put it: “Through the Incarnation of the Word the Mind whence all things proceed has been declared, and its Agent and Ordainer, the Word of God Himself. He, indeed, assumed humanity that we might become God.”

Playing Our Part

To some Christians today, that last statement might sound shocking. However, Fathers like Maximus are clear that this deification (theosis) happens “by grace” not nature. Thus, Wood emphasizes that our embodiment of divine life is possible only in and through the person of Jesus Christ. The Word of God grounds all creation, makes its salvation possible in his Incarnation, and through our salvation accomplishes the end of all things. Salvation, thus, consists not only of a change of status but an endless transformation of each and every person, requiring both the action of divine grace and the free cooperation of our will—for otherwise our will could not be healed. (And Lord knows we need it!)

Creation is God’s symphony; Christ, our composer.

The wide-reaching implications of this cannot be overstressed, and here I must go beyond Wood to offer some tangible examples, though I hope still in the spirit of The Whole Mystery of Christ. We receive divine grace through the sacraments, but we then embody that grace—which is nothing less than God himself—through virtue. We acquire virtue through asceticism, denying ourselves in all things for the sake of love, dying and rising with Christ daily.

Thus, in all our vocations, we live out humanity’s one true vocation: to bring Christ, actually not metaphorically, to all the world and to unite all the world to him. From the tired parent changing a baby’s diaper in the middle of the night; to the janitor cleaning yet another restroom catastrophe; to the musician practicing her instrument; to the student studying for exams; to the athlete hitting the gym; to the writer revising his submission; to businesspeople, conservationists, yes, even politicians—all of us in every aspect of our lives can and ought to embody the mystery of Christ. Even a seventh-century monk, unjustly tortured, abandoned, and forgotten in his own time. Even adjunct professors. Maybe even sinners like me.