Debt can be a cruel master, but it can also be a powerful servant. Debt is a tool. And like any tool, debt can be dangerous to those who misuse it and a snare to those who rely on it too much. It can also harm others if used badly. As Christians, we should not fear or shun using debt anymore than we should fear or shun weapons or fire or technology or power.

In our debt-ridden age, paying as we go might seem the most prudent and God-honoring way of handling our finances. But the Bible suggests it’s not that simple.

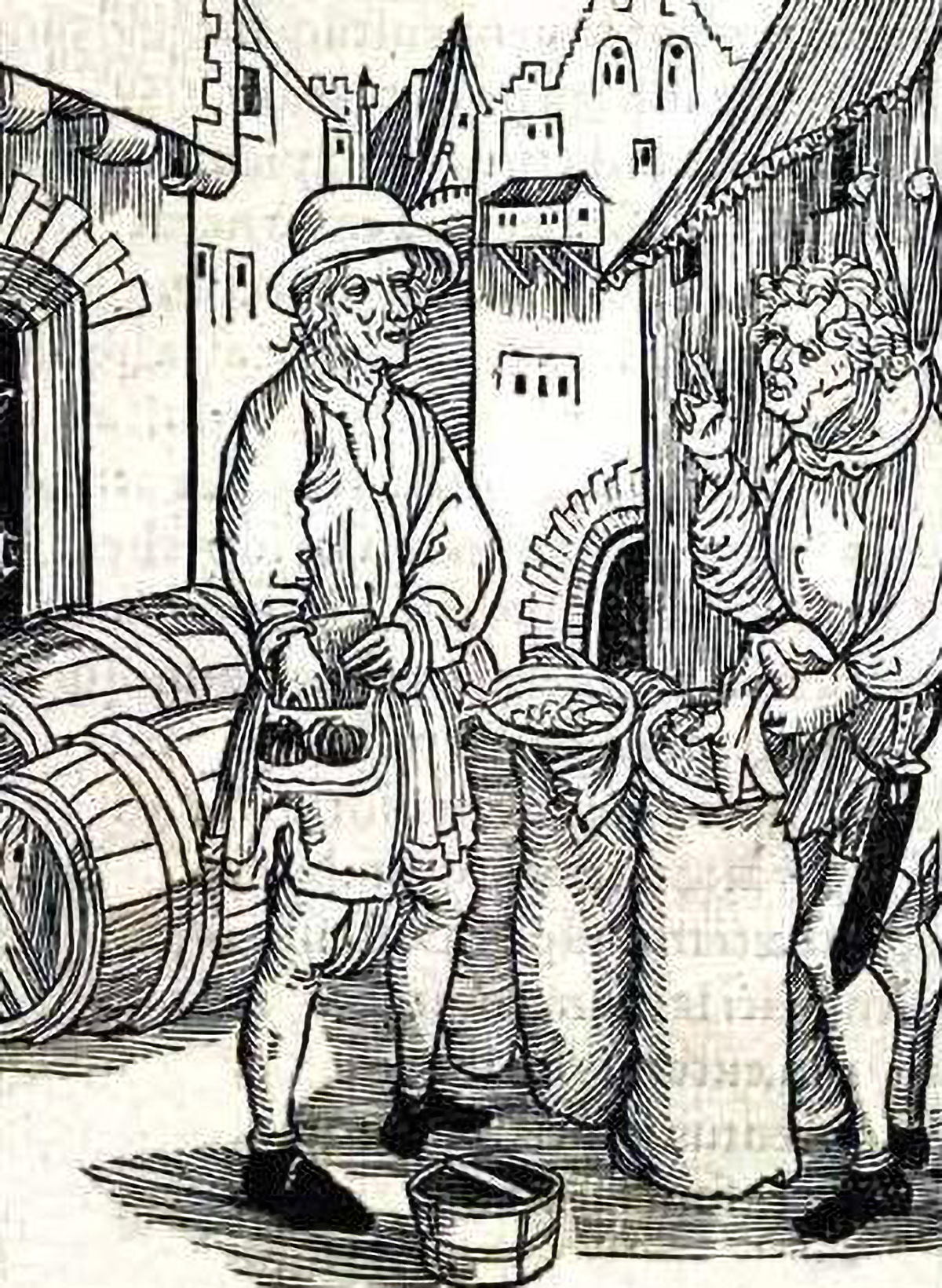

There are many perspectives on debt. From the hostility of Dave Ramsey to the embrace of Richard Kiyosaki, from the condemnation of usury (lending at interest) by Aristotle and Aquinas to the approval of usury offered by John Calvin, debt can be a complicated moral, financial, and spiritual issue. Although today people think of usury as “excessively high interest” debt, historically usury referred to all lending at interest—and that is how I will use the term in this essay.

Considering God’s purposes for humanity from the cultural mandate to the greatest commandments, historical treatments of debt, whether embedded in the Hebrew scriptures, discussed by ancient Greek philosophers and medieval theologians, or as used by men and women in a modern economy, will reveal that borrowing and lending at interest are morally permissible and can promote human flourishing.

The Cultural Mandate and the Greatest Commandments

Theologians have long noted “the cultural mandate” in the first chapter of the Bible. After creating Adam and Eve, God tells them to “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth” (Gen. 1:28, ESV). Before the fall and the curse of sin, God intended men and women to have families, cultivate the earth, domesticate animals, and engage in other forms of cultural and economic activity.

Working, creating, and building involve stewarding resources well and developing technology. Furthermore, creating wealth provides us means for obeying the greatest commandments: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets” (Matt. 22:37–40).

We can demonstrate love for God by how we use our physical resources. God required regular material sacrifices in Israelite worship. In the New Testament, God commends the sacrificial giving of the widow’s mite and the woman who poured perfume on Jesus’ feet. God wants human beings to show Him love and honor with their wealth.

We can also love our neighbor with our resources. In both the Old and the New Testaments, loving one’s neighbor almost always involves material care—sharing or giving of one’s resources as well as forgiving debts (Lev. 25:39–40). Examples abound, from Abraham hosting angels, to Boaz providing for Ruth and Naomi, to David and Mephibosheth, to Elijah and Elisha toward the women who cared for them, to the sharing of all things in common (Acts 2: 44–45), to the gentile churches sharing resources with the church in Jerusalem during a famine.

The cultural mandate and the two greatest commandments demonstrate the importance and purpose of wealth, and therefore of debt. They also explain why many passages in Scripture prohibit lending at interest (usury) and taking profit. In those situations, doing so harmed one’s neighbor, and by extension the community, which reflected badly on God and displayed callous selfishness rather than love. Similarly, philosophers from Aristotle to Aquinas condemned usury because they thought its use was not consistent with the flourishing of one’s community or loving one’s neighbors—especially the poorest and the most vulnerable.

In agrarian societies, most people produced barely enough to survive. Children would rarely be richer than their parents. Income did not usually rise over the course of one’s life as it does today. The risk of starvation was always present for most people. This context presents a problem when you borrow something. Not only do you have to return what you borrowed, but you must generate some surplus to pay interest. That was a nearly impossible task for most people and often led to their selling themselves or their family into slavery.

Borrowing and lending at interest are morally permissible and can promote human flourishing.

But borrowing and lending in our modern era are not inherently sinful. With economic growth and prosperity, borrowing is not undertaken because of dire circumstances only. In fact, wealthy people tend to borrow much greater sums than the poor do. In class, I sometimes tell my students, most of whom are borrowing tens of thousands of dollars to pay for college, that I have borrowed more money than all of them put together. Yet I am far from poor—in fact, the reason why I can borrow so much is because I am not poor! I have assets, investments, and income to service loans and pay interest, and I can put that borrowed money to productive uses in ways that didn’t exist a thousand years ago.

Debt in the Torah

Considerations of usury in the Old Testament are less about the practice of lending itself than about the particular harms caused by the practice in certain contexts. The Israelites were literally family. Therefore not sharing was reprehensible and punished severely by their laws. Furthermore, God hates people engaging in usury in ways that enslave their neighbors or harm and exploit the most vulnerable.

Old Testament authors saw lending in a very particular light and context: rich lending to poor; charging interest as harmful, almost punitive; and lending as power and borrowing as weakness or disadvantage. Nor were they wrong to see it this way.

In ancient and medieval societies, people borrowed because of tragedy, weakness, or desperation—a drought, a blight, the death of a husband or father, etc.—hence the importance of stories about widows and orphans. The poor would borrow from those with wealth, influence, and power. As I mentioned earlier, God created rules regarding slavery, lending, and Jubilee to protect the vulnerable and promote shalom in a society of brothers and sisters.

At first glance, God appears to take a very dim view of usury. He repeatedly prohibits the Israelites from employing usury and taking profit from their fellow Israelites:

Take no interest from him or profit, but fear your God, that your brother may live beside you. You shall not lend him your money at interest, nor give him your food for profit. —Leviticus 25:36–37

If a man is righteous and does what is just and right—if he … does not lend at interest or take any profit… he shall surely live, declares the Lord God. —Ezekiel 18:8

You shall not charge interest on loans to your brother, interest on money, interest on food, interest on anything that is lent for interest. —Deuteronomy 23:19

Whoever multiplies his wealth by interest and profit gathers it for him who is generous to the poor. —Proverbs 28:8

Who shall dwell on your holy hill? He … who does not put out his money at interest and does not take a bribe against the innocent. —Psalm 15:5

While this may seem like a sweeping condemnation of lending money at interest, deeper consideration of the context suggests that God is not condemning usury per se, but rather abusive uses of usury. Consider that: (1) these condemnations take place within a specific set of relationships and situations; (2) other passages allow and even encourage lending at interest; (3) Scripture condemns lending, not as inherently sinful (like, say, adultery or worshiping an idol), but as one of a variety of practices that can be used sinfully—namely, not loving one’s neighbor and not caring for the poor.

Notice, for example, the connections between poverty, borrowing, and debt. The Pentateuch addresses usury in Exodus 22, Leviticus 25, and Deuteronomy 15, 23, and 28. In Exodus 22:25, God tells the Israelites that “if you lend money to any of my people with you who is poor, you shall not be like a moneylender to him, and you shall not exact interest from him.” Notice that the command explicitly talks about lending to the poor. This passage stresses caring for the poor, and it condemns usury as harming or neglecting them.

This fits the preceding verse (22), which talks about not taking advantage of widows and orphans, who would be the poorest and most vulnerable people in society. It also fits the subsequent verses (26–27) about the importance of returning a poor neighbor’s pledged cloak before nightfall because it could be his only cloak and he will be more exposed to the elements if you keep it.

The Leviticus 25:36–37 passage is similar. Before the verse about not charging interest, we are explicitly told that the borrower is poor and unable to support himself. God says we have a responsibility to care for such a brother. Then comes the prohibition: “You shall not lend him your money at interest, nor give him your food for profit.”

God seems focused on the welfare of the poor brother, not on the inherent sinfulness of borrowing and lending.

God seems focused on the welfare of the poor brother, not on the inherent sinfulness of borrowing and lending. By the way, the broader context of this chapter in Leviticus is the year of Jubilee, when debts were to be forgiven and Hebrew slaves were to be freed. God institutes the year of Jubilee because He brought the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt: “For they are my servants, whom I brought out of the land of Egypt; they shall not be sold as slaves. You shall not rule over him ruthlessly but shall fear your God” (Lev. 25:42–43, emphasis added). Canceling debts freed the poor from slavery and destitution.

There is another significant reason why this was part of the Mosaic law: God’s ownership of the land and the inheritance he intended for his people. Returning land in the year of Jubilee is part of God’s rules of inheritance, as the land ultimately belongs to Him.

Deuteronomy 15:8 has similar commands about caring for the poor and not charging them interest, but it adds a further detail of what biblical authors assume when they talk about charging interest: that lenders are rich and borrowers are poor. Why else would God tell Israel multiple times that if they follow him they will be blessed, wealthy, and lenders to the nations rather than borrowers?

For the Lord your God will bless you, as he promised you, and you shall lend to many nations, but you shall not borrow, and you shall rule over many nations, but they shall not rule over you. —Deuteronomy 15:6

The Lord will open to you his good treasury, the heavens, to give the rain to your land in its season and to bless all the work of your hands. And you shall lend to many nations, but you shall not borrow. —Deuteronomy 28:12

If they don’t follow God, however, they will be poor and borrow from the nations: “He shall lend to you, and you shall not lend to him. He shall be the head, and you shall be the tail” (Deut. 28:44). The author of Proverbs echoes this idea: “The rich rules over the poor, and the borrower is the slave of the lender” (22:7).

Similarly, why would God allow them to charge interest to the nations but not to their brothers: “You may charge a foreigner interest, but you may not charge your brother interest” (Deut. 23:20)? In fact, when it comes to a brother, “you shall open your hand to him and lend him sufficient for his need, whatever it may be,” instead of shutting your hand and hardening your heart to your poor brother.

I should note that biblical authors are not always talking about a formal business transaction when referring to borrowing and lending. Letting someone use your hammer or drill or borrow your car for a day, giving a friend your umbrella temporarily, these would all be modern examples of the kinds of lending the Bible speaks about in Psalm 37:26, Psalm 112:5, and Proverbs 19:17, for example.

We can’t always distinguish when “lend” really means “give.” We’ve all experienced situations where we have “lent” something and never gotten it back. This can be irksome if we expected it back, but we will often lend not expecting anything in return. Luke 11:5 illustrates how “lend” can be used to mean “give”: “And he said to them, ‘Which of you who has a friend will go to him at midnight and say to him, “Friend, lend me three loaves.”’”

This is clearly not a business transaction. The friend may hope or expect that you will give him some loaves in the future, but you will clearly not be returning these three loaves the way you would return a plow.

We find more condemnation of usury in Nehemiah, Isaiah, and Ezekiel. These condemnations fit the pattern I’ve described above: God requires us to care for the poor and to practice generosity rather than greedily seeking gain when we interact with the poor and the vulnerable. Doing so honors God and recognizes that He did not make us to rule ruthlessly over our fellow men and women as slaves.

Returning land in the year of Jubilee is part of God’s rules of inheritance, as the land ultimately belongs to Him.

Nehemiah condemns the wealthy Israelites for not dealing generously with their poor brothers and sisters. Instead, the wealthy Israelites charged the poor so much interest and profit that the poor say, “[We] are mortgaging our fields, our vineyards, and our houses to get grain because of the famine. … [We] are forcing our sons and daughters to be slaves, and some of our daughters have already been enslaved, but it is not in our power to help it, for other men have our fields and our vineyards” (Neh. 5:3–5).

These verses show something else God cares about—people’s ability to generate income, which in agrarian societies primarily consisted of food and clothing, to provide for themselves, and to be part of the community. Not only are the poor indebted in Nehemiah’s time but they also have no means to improve their situation because they have mortgaged or sold their productive assets (fields and vineyards). They are permanently poor now and slavery must inevitably follow. Nehemiah explicitly calls out the charging of interest (in violation of the Pentateuch’s prohibitions) as the main problem: “I took counsel with myself, and I brought charges against the nobles and the officials. I said to them, ‘You are exacting interest, each from his brother.’ And I held a great assembly against them. … Let us abandon this exacting of interest” (Neh. 5:7–10).

The context suggests that the problem stems from the particular use of usury, not from the activity itself. Such a reading resolves the otherwise puzzling passages about lending to foreigners and Jesus’ parable of how the servant should have given the talent to the bankers to lend with interest (Matt. 25:14–30).

Ancient Philosophers and Medieval Theologians

Before the 18th century, there were no “economists.” But philosophers and theologians often considered economic questions like “What is wealth and how should it be used?” and “What does justice in the marketplace look like?” They often wrote about usury and generally concluded that it was unjust.

Aristotle, for example, argued that usury was unnatural and a distortion of an appropriate use of wealth. In seeking to live well, people need all kinds of material goods. Many of these goods could be produced within an extended household, but not all of them. Aristotle approves trading one’s surplus for a roughly equivalent amount of someone else’s surplus (e.g., a bushel of olives for a bushel of grapes). Money can serve a useful intermediary function in these exchanges, but fundamentally people are trading commodities for other commodities.

Usury, however, does not fit this paradigm. The lender begins with money and ends with more money. He both gets more than he gives and mistakes means for ends. There are “natural” limits to how much commodities one gathers. At some point people have enough gallons of olive oil or pairs of shoes or sets of dishes. Collecting thousands of these things does not make sense. But collecting a thousand dollars does. Or ten thousand. Or ten million. In fact, there is no “natural” limit to one’s monetary accumulation.

Regarding trading practices, Aristotle writes:

The most hated sort, and with the greatest reason, is usury, which makes a gain out of money itself, and not from the natural object of it. For money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest. And this term interest, which means the birth of money from money, is applied to the breeding of money because the offspring resembles the parent. Wherefore of all modes of getting wealth, this is the most unnatural. (Politics, Book I)

Beyond the danger of unrestrained acquisitiveness, Aristotle was also concerned about usury’s injustice. Just exchange requires trading equal value. But with usury, the lender receives more money or value than he gives.

Thomas Aquinas similarly condemns usury but offers different reasons. He, too, criticizes usury for not being an exchange of value for value—which justice requires. But he picks up on the rich-poor dynamics of lending, going so far as to say: “He who gives usury does not give it voluntarily simply, but under a certain necessity, in so far as he needs to borrow money which the owner is unwilling to lend without usury” (Aquinas, Summa Theologica, “Treatises on the Virtues,” Question 78). This fits the biblical or agricultural paradigm of borrowing being used only in dire circumstances. The concern seems to be about oppression and the lack of virtue in lending at interest.

Reformers like John Calvin took a broader view of usury. Calvin understood that money, along with clearly defined and protected property, was a tool men can avail themselves of to produce more. And producing more fulfilled the cultural mandate. Besides appreciating the prospect of productive loans, the Reformers also added nuance to what borrowing and lending consisted of—namely, it is actually a kind of purchase. In that case, principles of charity and justice apply rather than blanket prohibitions. Furthermore, when lending for a productive use, the lender shares in the fruit or profit of the enterprise when they receive interest.

One must consider the position of borrowers to avoid taking advantage of their situation or impoverishing them. But Calvin also thought it was possible for borrowers to defraud the lender if they had the means of repayment but chose not to repay. This was tantamount to theft. As Christians, he argued, we are primarily under the law of charity, both in terms of how we use our resources and in how we borrow and lend. He would have had no patience for loan sharks, payday lending, or high credit-card interest rates.

Borrowing and Lending in 2023

Today Christians should consider the ethics and prudence of borrowing and lending. As borrowers, we should feel confident that debt is a legitimate tool for us to use prudently. I suggest we use the paradigm of productive debt versus unproductive debt. Productive debt increases our capabilities to work, create, steward, and bless others. Unproductive debt creates burdens, hardships, and reduces our ability to steward resources and bless others.

With debt you acquire an asset right away and then increase your “ownership” of it over time by paying off the debt. Borrowing to buy a house can be a productive use of debt if we are prudent: not taking out more debt than we can reasonably repay with our current and future job prospects or taking significant risk by borrowing the entire value of the house, which may decrease in value over time. Similarly, borrowing to buy or build housing for others can be another productive use of debt.

Borrowing money can also be justified when put toward other productive endeavors like starting a business or paying for education or for job certification. Often these loans have reasonable interest rates and repayment schedules. And most importantly, from a theological perspective, these kinds of loans can increase our capacity to carry out the cultural mandate and our means of loving our neighbors.

In contrast, unproductive borrowing tends to center on consumption and should generally be avoided. Most borrowing for consumption damages one’s financial position—leaving us with fewer resources to share with or give to others. Borrowing for consumption is also usually economically unproductive. Buying a boat or new clothes or dining out are generally superfluous economic activities. This doesn’t mean that owning or enjoying these things are necessarily sinful, but they are not part of the cultural mandate of creative production.

Of course, in rare or extreme cases, borrowing for consumption may be productive. After all, we need food and clothing and shelter in order to live and flourish. While there may be times, often because of misfortune, where we need to borrow to pay bills or to bridge a period of unemployment, such borrowing limits our capabilities. Our options for work, spending, and giving shrink because we have to service our debts. Borrowing for consumption can also amplify our passions and our appetites rather than our creative and productive capacities.

When it comes to lending, Christians need to exercise discernment. Lending at well above market rates should be scrutinized closely. Are we able to charge such a rate because someone is desperate or stuck? Are we their only option for funds? If so, we should remember the teaching of the Old Testament: Are we impoverishing a brother or friend when we should be aiding them? There is no simple rule for the diverse situations we might face.

After all, the risk of default may justify an unusually high rate of interest. But would offering someone a lower rate show more care? Should we offer the loan without interest? Or give the resources away entirely? Or could the loving thing involve not enabling the other person to spend more money? Answering such questions requires wisdom.

In the marketplace of impersonal exchange, however, there is greater latitude in what interest rates we may charge. I suppose, like gambling, Christians should generally avoid creating or working in payday or credit card or consumer debt businesses that deal primarily with unproductive borrowing by people in difficult circumstances. These kinds of businesses have little to do with expanding people’s ability to create or to serve others. Instead, they tend to cater to people’s appetites—or desperation—while ultimately reducing their options and capacity to love God and their neighbor.

So, how should Christians think about debt? As a powerful servant or a cruel master.

Although I have focused on individual borrowing and lending, similar principles apply to government borrowing. Unfortunately, many politicians and governments borrow money to pay for consumption of various kinds, rather than for productive investment. This can hobble countries as their interest and debt payments crowd out other forms of public spending.

President Biden’s proposal to forgive large sums of student debt provides an interesting test case. First, consider what the policy would do. It would “forgive” $10,000 (or even more) of someone’s student debt—that is, money borrowed directly or indirectly from the government to pay for college. While that improves their financial position, it means that the lender (i.e., the federal government) will now receive that much less money from debt repayment. A loan has become a gift.

Now, in a private setting, if a lender chose to forgive someone’s debt, we would consider it an act of charity. But this case is more complicated because the federal government is the lender and it represents the American people. Furthermore, it is only a couple of politicians deciding, on behalf of everyone, to make this “gift.” And it will mean either higher taxes to compensate for less debt-repayment dollars or greater borrowing by the federal government. So we are warranted in asking: What does this policy produce? If the answer is not much, then we can lump this policy in with hundreds of others that create debt for consumption rather than production, further undermining the financial capacity of the nation’s government.

A Tool, Not a Vice

We should recognize lending and borrowing as potentially useful, not as inherently sinful. Rather, debt is a tool that can improve our stewardship or detract from it; that can bless others or take advantage of their situation. To shun this tool would be to close our eyes to a powerful means of advancing God’s work on earth and for promoting human flourishing. But to embrace it unquestioningly sets the stage for our financial ruin or for our participation in the financial ruin of others.

And as with any tool, charity should rule along with prudence and wisdom. We can learn how to use debt better with time—just as you can get better at operating a machine or driving a vehicle with practice. Our borrowing should be for productive uses. And our lending should be tempered by charity and generosity.