Lutherans have been in Russia since the time of the Reformation. Ivan the Terrible, wanting to bring Russia into the 16th century, invited German craftsmen and tradesmen to settle in the country. He allowed the first Lutheran church to be built just outside Moscow in 1576. Four years later, he ordered it to be burned down.

The persecution of Christians by the old Soviet regime seems both overwhelming and lost in time. Yet it began by the slow erosion of religious liberty we’re seeing here and now.

By Matthew Heise

(Lexham Press, 2022)

That sums up conditions for Russian Lutherans under the czars. Sometimes they were favored; at other times, repressed. Until the 20th century, it was illegal for any ethnic Russian to have any religion other than Russian Orthodoxy.

And yet the czars had a habit of marrying Lutheran princesses—though a condition of the marriage was that she convert to Orthodoxy—a practice continuing all the way to the final ill-fated holder of that office, who was married to Alexandra of Hesse. Peter the Great was married not to a princess but to a Lutheran serving girl; one of those Lutheran princesses, however, would become Catherine the Great. Both of these “Great” monarchs brought into the country large numbers of Lutheran farmers, merchants, and well-educated professionals.

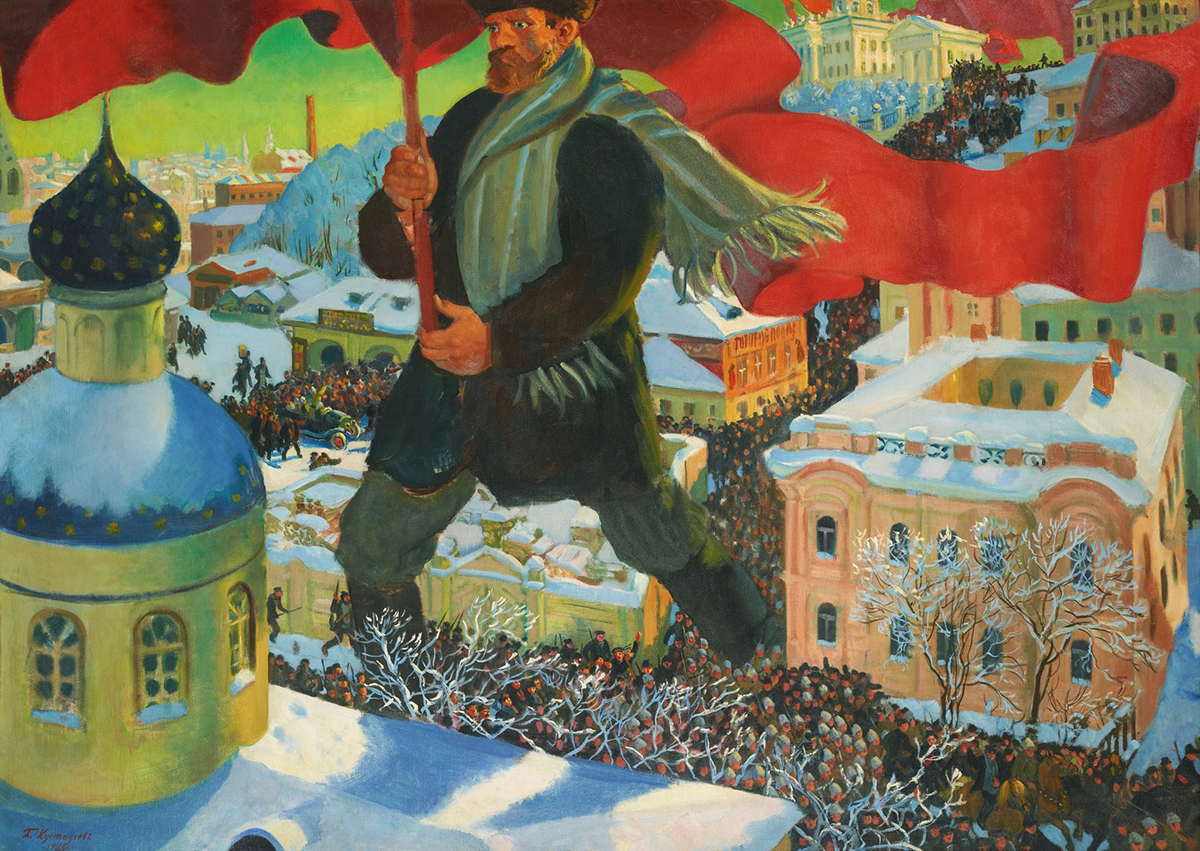

The Germans were not the only Lutherans in Russia. The Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union included the staunchly Lutheran Ingrians, Estonians, and Latvians, as well as a smattering of Finns, Swedes, and Lutheran Armenians. By the 1917 revolution, there were 3,674,000 Lutherans scattered throughout Russian cities, villages, and the vast countryside.

The Gates of Hell by Matthew Heise, director of the Lutheran Heritage Foundation and a long-time missionary in the region from the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod, is a history of the Lutheran church in Russia from the time of the Bolshevik Revolution to World War II. The book is a gripping and instructive account of the state’s efforts to use economic, cultural, legal, and violent means to exterminate a church.

Class Struggle vs. the Golden Rule

At first, with the czar’s restrictions lifted, the Lutherans flourished. They managed to organize themselves into one church body, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Russia, with two bishops. They opened a seminary in Leningrad. They worked with American government and church-related relief agencies in the famine and food shortage that followed the revolution.

Then the Bolsheviks began to implement their anti-religion policies. They proclaimed freedom of religion but only as a private matter; all religion had to disappear from the public square. They confiscated church property, took over all schools, and censored religious publications.

Priests and pastors were labeled “non-productive elements,” since they engaged in no physical or other productive labor, and so were excluded from the “workers’ paradise.” They were described as “former persons,” along with czarist aristocrats and functionaries of the old regime. As such, they had no rights of citizenship, could not vote, were given no food rations, lost their parsonages, and had to pay higher taxes. In addition, their children were not allowed to attend universities.

In response, church members, many of whom also lost their homes and farms, tithed like never before to support their pastors and their congregations. Lutherans from other countries, especially the Russian Germans who had migrated to the American Midwest, sent contributions.

The Bolsheviks proclaimed freedom of religion but only as a private matter; all religion had to disappear from the public square.

Then came Stalin’s first Five-Year Plan, in 1929, one of whose goals was the complete elimination of Christianity in Russia. The main target was the very belief in God, which violated the Marxist tenets of “scientific materialism.”

But the Communist Party sought also to erase Christian ethics. “Love your neighbor” violated the Marxist principle of “class struggle.” Thus, pastors could be charged with “preaching class peace.” Lutherans had an extensive network to help the poor and the disabled, but this was held to compete with the state and to keep the deprived “in thrall to their exploiters.” Consequently, the church was defined as an enemy of the state. One of the Lutheran bishops summed up the goal: “Everything that is connected to the Christian faith or reminds one of it must disappear from the life of the people and its individual citizens.”

It wasn’t just a matter of punishing church leaders and other religious believers for “anti-Soviet activities” or for being “counter-revolutionaries.” Communists assumed that religion would simply die out if they could prevent it from being transmitted to children. But even more than that, the very reminders of religion—the very memory that there used to be a religion—had to be erased.

Although Heise chronicles what happened specifically among the Lutherans, as their ethnic identities and foreign ties brought on an additional level of persecution, the Communists’ primary target was the Orthodox Church, which was woven into the fabric of Russian culture. Most of the anti-religion policies he describes were carried out against not only Lutherans and Orthodox, but also Catholics, Baptists, Pentecostals, Jews, and Muslims, as well as other religious minorities.

Erasing the Sabbath, Crushing the Spirit

In an effort to make religion disappear, the Party imposed a new, five-day week, with four days of work, then one day off. The cycle was staggered so that the day off fell on different days for different individuals. The purpose was to eliminate Sunday. The day set apart for worship ceased to exist. But churches responded by meeting once a week at night.

Taxes were weaponized. Exorbitant taxes were levied on religious workers and institutions, including a special tax “to support atheist culture.” Heise records a church in 1928 having to pay taxes of 393 rubles; in 1931, it had to pay 3,609 rubles. Other economic sanctions were designed to force churches out of existence. Churches had to pay up to 22 times the normal rate for utilities. When a congregation could no longer pay its taxes and other fees—and eventually none of them could—its building would be taken over by the state, to be converted to a factory, a theater, or, in the case of St. Peter’s in Leningrad, an indoor swimming pool.

The new policy forbade churches from holding religious instruction for children. So pastors met in their apartments with Sunday school teachers to go over the lessons for the week. The Sunday school teachers then met with children in their apartments.

But informers from the League of the Militant Godless uncovered this work-around. The pastors responsible were arrested. So were the elderly women and teenage girls who taught Sunday school. They were sent to penal labor camps for as long as 10 years. Seventy-year-old pastors and aged church ladies were given picks and shovels to dig out Stalin’s arctic canal. The elderly died in the brutal conditions, but the younger pastors and young women who survived completed their sentences, after which they returned to their church work.

In 1937 a government poll was taken designed to measure the success of the anti-religion policies. Citizens were asked, “Do you believe in God?” Despite the elimination of Sunday worship, the restrictions on religious teaching, and the suppression of the church, a majority of Russians—56.7%—not only said yes but were bold enough to admit it despite the consequences, as some respondents lost their jobs or their university enrollment because they professed their belief in God.

The Communists were flabbergasted. So they launched a more thorough wave of persecution, targeting not only pastors but also choir directors, organists, and ordinary laypeople. And they increased the use of the death penalty.

The German Factor

The German Lutherans faced yet another danger. Once Hitler came into power and World War II approached, Stalin declared that all German citizens and Russians of German origin were subject to arrest. They were all suspected of Nazism and of spying for Germany. The NKVD—the predecessor of the KGB—began rounding up pastors and church members. The donations the Lutheran church had received from foreign churches became prima facie evidence of treason, subversion, and espionage. Church youth groups were defined as Nazi cells. Sermons were interpreted as pro-Nazi agitation. In at least one case, a pastor’s preaching on “the Kingdom of God” was interpreted as a symbolic reference to the Third Reich.

One might wonder whether there was, in fact, something to those charges. Heise, who had access to the records of NKVD interrogations, gives evidence of torture and coercion but also some confessions. Might German nationalism and support for Hitler have filtered into Russia? But Heise uncovers two confessions from NKVD agents, including the chief interrogator of the Leningrad Lutherans who was himself arrested years later and admitted that the cases against the believers were all fabricated and that the recorded testimonies were written by the officers themselves. As it turned out, the NKVD, like other elements of the Soviet economy, had quotas to fill.

In Stalin’s “German operation,” some 42,000 Russian citizens of German background were executed. Still more, including entire villages, were put into boxcars and shipped to Siberia. Nevertheless, Heise records the astonishing faith of the pastors and laity who persisted even as the persecutions got worse and worse. We read about the seminary, whose students kept coming, even though they knew that upon their ordination they would become “former persons,” lose all their rights, and be targeted themselves for arrest and possible execution. Still, they kept studying. The seminary had to spend half its budget on taxes. One by one the professors got arrested. Yet, when no more were left, the administrators started teaching their classes.

Bishop Meier, knowing that before long no church buildings would be available and the last pastor would soon be gone, began teaching parishioners how to keep the faith alive without clergy. He taught his people how to baptize, how to conduct weddings and funerals, how to teach their children the catechism, how to come together for prayer and worship.

On November 27, 1937, the last pastor was killed.

Glasnost and the Gospel

Heise’s book ends with the apparent extinction of the Lutheran Church and the beginning of World War II. It doesn’t continue with the story of those Lutherans in Siberia and elsewhere who did what the bishop had taught, preserving and handing down their faith by means of the ordinary practices still performed today by Lutherans everywhere—learning the catechism by heart, learning the hymns, memorizing Bible verses—and carrying out the priesthood of all believers by worshiping and baptizing.

Heise does, though, include an epilogue, which jumps past the postwar years to Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost policies and to the collapse of the Soviet Union. During that time, the victims of Stalin’s “Great Terror,” including the Lutherans, were cleared of the accusations against them. Survivors and their children and grandchildren came out into the open and identified as Lutheran. They organized into congregations. Church property, including the “swimming pool” church, was restored to them. The old, vandalized buildings once again became houses of worship. They had pastors again. Just as Jesus promised of His body, the church, the gates of hell did not prevail against the church in Russia.

In reading this chronicle of persecution, we can’t help but see the parallels, faint now but real, with today’s leftist opponents of religious liberty. Religion can be tolerated only if it remains inside a person’s head and is neither acted upon nor expressed in the public square. “Everything that is connected to the Christian faith or reminds one of it must disappear.” Children should be indoctrinated against the beliefs of their parents. Religion is only a mask for oppression. And we see how religion can be persecuted not only through violence but also through economic sanctions (threatening churches with the tax code), cultural pressures (undermining the values Christians try to instill in their children), and the law (punishing those who won’t conform to the prevailing secularist ideology).

Reading this book is a heart-wrenching but inspiring experience. It begins with the mundane efforts to bring Russian Lutherans into one church body, so we hear about meetings, fundraising, personality conflicts, and church politics. This is the ordinary stuff of the “institutional church” that so many American Christians are tired of. But then the pressures begin and intensify, grow worse and worse, more and more lethal. Yet we see these ordinary pastors, church ladies, Sunday school teachers, youth group members—so very much like those we know in our own congregations—holding on to Christ, trusting in God’s Word, no matter what the NKVD does to them, and becoming blessed martyrs, and in some cases even living witnesses.