On the afternoon of November 3, 2021, I sat alone at a table in the Orlando Airport TGI Fridays, exhausted. Equally travel-weary families (or at least parents), whose children still bustled with energy, surrounded me. I was grateful for getting through TSA security with plenty of time for a meal before my flight, and grateful to be—for the first time in three days—alone with my thoughts. When my salad arrived, I pushed aside my notes from NatCon 2, the National Conservative movement’s flagship conference—a whirlwind of keynotes, panels, and breakout sessions—and my thoughts turned to The Count of Monte Cristo: “How did I escape? With difficulty. How did I plan this moment? With pleasure.”

The publication of a “Statement of Principles” has clarified many of National Conservatism’s aims and premises. Yet the false dichotomy at the heart of this explanatory text only reinforces many of the original objections to the movement itself.

I later crafted those notes, additional research, conversations, and a dash of humor into an article for the Winter-Spring 2022 issue of Religion & Liberty. In that piece, “What I Saw at the National Conservatism Conference,” I tried to come to terms with what “National Conservatism” meant. A neat and tidy definition eluded me. Such definitions are always difficult for political, and especially ideological, movements.

National Conservatism was by turns various things: a brand, an emerging political coalition, and an attitude. The brand I judged amorphous and thus harmless and uninteresting. The political coalition: undertheorized and untested. The attitude: an invitation to stop being polite and start being real, and positively dangerous in its conflation of acrimony with authenticity. In the past year, much has changed, making the “National Conservative movement” worth revisiting. The “National Conservatism” on offer at NatCon 2 was amorphous but anti-establishment, billing itself as “against the dead consensus.” As outsiders, the NatCons sought political alliances with “anti-Marxist liberals” to realize their political ambitions, and their often strident tone could be seen as a rhetorical strategy to raise the movement’s profile.

The “National Conservatism” at NatCon 3 in 2022, however, was different. Kevin Roberts, president of the Heritage Foundation, long the institutional center of what has been called “Conservatism Inc.,” referred to the NatCon movement as “ours.” The conference’s most celebrated speaker, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, is perhaps—with the popularity of former President Trump waning as I write this—the nation’s most popular conservative politician. National Conservatism has been rediscovering itself as conservatism itself. Yoram Hazony, president of the Edmund Burke Foundation, explicitly made the case for this in his popular revisionist history, Conservatism: A Rediscovery.

Only the attitude appears unchanged, leading Stephanie Slade, senior editor at Reason and fellow in liberal studies at the Acton Institute, to refer to the movement as “will-to-power conservatism.” As it turns out, this is not the story of one man’s escape from a conference, but a movement’s attempted escape from idiosyncrasy into something ostensibly mainstream, or at least comprehensible. It was a classic mistake, however, one Michael Chabon forewarns all would-be escapists about in his novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay: “Forget about what you are escaping from. … Reserve your anxiety for what you are escaping to.”

A Movement with a Home

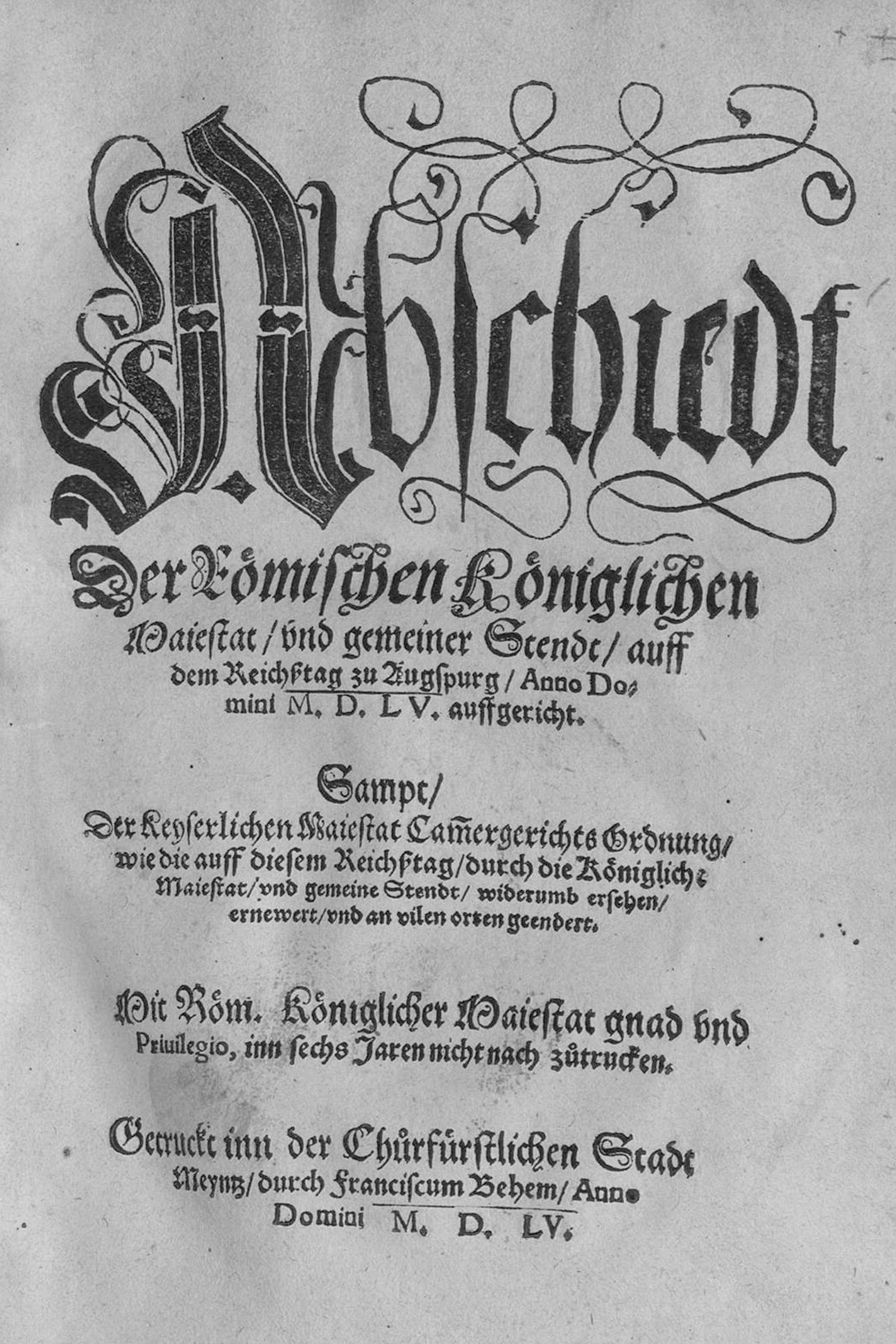

The National Conservative movement continues to evolve. Its rise in prominence is merely one example. Its substance has crystalized as well—a natural development in the course of all movements that pose both peril and promise. The great upheaval in the religious life of 16th-century western Europe, the Reformation and Counter-Reformation both, serve as instructive examples. In his magisterial work The Reformation: A History, Diarmaid MacCulloch observes that, as the Reformation progressed, it “witnessed a process to which historians have given the unlovely but perhaps necessary jargon label ‘confessionalizaton’: the creation of fixed identities and systems of beliefs for separate churches which had previously been more fluid in their self-understanding.” Rival churches and traditions “buttressed their differing positions with an increasing array of confessional statements, saying exactly what they did and did not believe.”

On June 15, 2022, the National Conservative movement entered into its own period of confessionalization with “National Conservatism: A Statement of Principles,” published in both The American Conservative and The European Conservative.(One of the most paradoxical features of National Conservatism is its international character.) An editor’s note preceding the statement disclosed, “The following statement was drafted by Will Chamberlain, Christopher DeMuth, Rod Dreher, Yoram Hazony, Daniel McCarthy, Joshua Mitchell, N.S. Lyons, John O’Sullivan, and R.R. Reno on behalf of the Edmund Burke Foundation.” The statement boasted a long list of signatories, including academics, a college president, journalists, a priest, a filmmaker, publishers, and think tankers the world over.

The statement’s multiple authors suggest that National Conservatism is a genuine movement, not merely the expression of any one individual’s idiosyncrasies. Its drafting on behalf of the Edmund Burke Foundation identifies it as having an institutional home. Its wide and diverse array of signatories evidences its range of influence. And most important, the statement’s collaborative and official nature, as well as its wide reception, affords it a greater weight than the op-eds, podcasts, conference talks, and books by individual authors that had defined the movement less perfectly in the past.

The substance of the statement itself, sans the editorial note and list of signatories, is bipartite. It begins with a concise three paragraphs that outline the identity of its confessors, their motivating concerns, the historical tradition to which they appeal to address those concerns, and the general political principle they see as best suited to address these concerns. The second part lists 10 discreet principles informed by the first. The principles are then each addressed in a single paragraph unpacking the NatCon understanding of them.

In the history of religious confessions, particularly those of the Reformation, there are two ways in which people viewed those confessions: valid “because” (quia) the confession is biblical or merely “insofar as” (quatenus) it is biblical. Does “A Statement of Principles” serve as an authoritative statement “because” or merely “insofar as” it faithfully captures the spirit of National Conservatism?

The editor’s note seems to indicate the latter, drawing attention to its culturally situated and contextual nature: “The statement reflects a distinctly Western point of view. However, we look forward to future discourse and collaboration with movements akin to our own in India, Japan, and other non-Western nations.” One can be an Indian or a Japanese “NatCon,” or at least akin to one, without holding to the letter of the statement or insofar as it captures a distinctly Western form of National Conservatism.

In his opening address to NatCon 3, entrepreneur and venture capitalist Peter Thiel seemed to suggest that viewing the statement, of which he was a signatory, too strictly would be a mistake: “It’s always a little bit hard to know exactly how to define our movement. I think it is strikingly heterogeneous … we’re not even some ‘happy clappy church.’” “A Statement of Principles” is a reliable guide to the movement not because it captures its essence but only insofar as it does so, even within its own Western context.

The Backlash

The “Statement” was well received by NatCons, whose enthusiasm might even be characterized as “happy clappy” upon its release. It resulted in no great schisms within the movement and only occasioned criticism from former fellow travelers who had already become estranged from the movement (more on this later).

Criticism from outside the movement, however, was more forthcoming. Libertarians, fusionist conservatives, and liberals both classical and contemporary offered critiques in line with those of the past, but many welcomed the statement’s more staid and irenic presentation of National Conservative ideas, free from some of the rhetorical pyrotechnics the movement had become known for.

Two “post-liberal” constituencies presented their own forceful criticisms as well. The first such constituency is represented by the authors of “An Open Letter Responding to the NatCon ‘Statement of Principles.’” This open letter includes an eclectic group of academics and thinkers among its signatories, including Phillip Blond, Jennifer Frey, John Milbank, James K.A. Smith, and the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams. All style themselves as “critics of contemporary liberalism … from both the Left and Right.” Their objections to “A Statement of Principles” are multifaceted, but all flow from what they believe to be the insufficient or mistaken theological grounding of the NatCon project.

The second post-liberal constituency was positively prescient in its criticisms of the main threads of “The Statement of Principles.” A month prior to their publication, Sohrab Ahmari, founder and editor of the online magazine Compact, delivered a stinging indictment of National Conservativism in his essay “The Return of Liberal Nationalism,” published on May 12, 2022. Ahmari had spoken twice at NatCon 2 in 2021; he is one of the aforementioned fellow travelers who had become estranged from the movement.

James Patterson, associate professor of politics and chair of the politics department at Ave Maria University, has provided the helpful descriptor of “neo-integralists” to describe this constituency, which includes Ahmari, Fr. Edmund Waldstein, Gladden Pappin, Patrick Deneen, and Adrian Vermeule. As Patterson detailed in his essay published in Religion & Liberty, “An Awkward Alliance: Neo-Integralism and National Conservatism,” this group had always been an uneasy fit within the emerging National Conservative movement.

Ahmari’s critique, although a post-liberal one, is offered on terms different from those of the first constituency noted above: that nationalism is not a sufficient ground on which to oppose liberalism and that National Conservatism is a fundamentally liberal project and better seen as a species of Liberal Nationalism. Whether or not Ahmari had access to “A Statement of Principles” prior to its publication, his piece offers a trenchant critique of the principles in any event.

As Kant observed, getting to the thing in itself (Ding an sich) is more difficult than it seems. The historical development of National Conservatism, the nature and limits of “A Statement of Principles,” and its reception among National Conservatives and their critics, are each necessary to understand and appreciate National Conservatism as confessed in the “Statement of Principles,” which opens by disclosing the identity of its confessors before the motivation for the movement itself: “We are citizens of Western nations…”

The management guru Stephen Covey advised those seeking to be highly effective to “Begin with the end in mind,” advice taken in the rhetoric of “A Statement of Principles.” Those who confess to National Conservatism do so from their identity as citizens of nations. Here Ahmari senses the pungent odor of liberalism, which he sees as nationalism’s natural bedfellow: “Liberalism and nationalism arose in tandem. … Rights-based citizenship made it necessary to delineate who counts as a citizen, and who doesn’t, and the answer more often than not came down to ethnic or linguistic groupings.” Such ethnic or linguistic groupings are commonly called “nations.” Privileging this identity, particular and national, was also a cause of concern for the drafters of the “Open Letter,” who asked, “What after all has underpinned the Western, European, and Christian civilisation that National Conservatism claims to defend and uphold if not a universalist ethical, spiritual and, yes, political vision?”

This is a very worthwhile question indeed, one Lord Acton explored extensively in his 1862 essay “Nationality”:

Christianity rejoices at the mixture of races, as paganism identifies itself with their differences, because truth is universal, and errors various and particular … in the ancient world idolatry and nationality went together, and the same term applied in Scripture to both. It was the mission of the Church to overcome national differences.

In the most startling manner here, we see the Christian liberal, post-liberal, and neo-integralist converge in their critique of the NatCons as privileging national identity over and above others, particularly a religious one.

It should be noted in fairness that here even the National Conservatives may sense a danger. While “A Statement of Principles” refers to national institutions, interests, traditions, constitutions, languages, and religions, it passes over any mention of ethnicity and explicitly denounces any racialist understanding of nation (see “Principle 10—Race”). However, on the question of immigration (“Principle 9”), it states that while immigration has historically been a great asset to Western nations, “today’s penchant for uncontrolled and unassimilated immigration has become a source of weakness and instability, not strength and dynamism, threatening internal dissension and ultimately dissolution of the political community.” It suggests unspecified “assimilationist policies” to mitigate this threat. Presumably such policies would encourage assimilation into national institutions, interests, traditions, constitutions, and languages—but what of religion?

The status of religion is made ambiguous by “Principle 4—God and Public Religion.” This principle privileges the Bible as “our surest guide, nourishing a fitting orientation toward God, to the political traditions of the nation, to public morals, to the defense of the weak, and to the recognition of things rightly regarded as sacred,” and commends its reading as a source of “shared Western civilization,” to be studied in schools and universities by believer and unbeliever alike. The Bible as national text is a strange category, somewhat more than literature to be appreciated but a great deal less than the Word of God.

“Principle 4” goes on to proclaim, “Where a Christian majority exists, public life should be rooted in Christianity and its moral vision, which should be honored by the state and other institutions both public and private.” While not specified, this principle would seem to hold for majority Jewish, Muslim, and Hindu nations. Allowances are made for religious minorities, who should be “protected in the observance of their own traditions, in the free governance of their communal institutions, and in all matters pertaining to the rearing and education of their children,” as well as “adult individuals,” who “should be protected from religious or ideological coercion in their private lives and in their homes.”

The course charted here is analogous to the principle of cuius regio, eius religio (“whose realm, his religion”), which underlay the 16th-century Augsburg Settlement, except here with the sovereignty of princes displaced by that of the people and the addition of some protection for religious minorities and persons within their private lives. Deep sectarian divisions among Christians in America complicate matters, making “Christianity and its moral vision” difficult to describe outside the level of abstraction. This Gordian knot becomes more impossible when one considers that sectarian boundaries among American Christians overlap largely with the racial and ethnic boundaries National Conservatives would rather avoid.

Perhaps the best that could be hoped for is the American civic religion of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which failed to satisfy not only non-Christians but Catholics and the then-emerging fundamentalist movement as well. Neo-integralists would simply, like Alexander, slice through this knot with the blade of political Catholicism, but there seems no reason to abandon our current liberal settlement, imperfect though it may be. For as Lord Acton observed, it is rooted in the New Testament itself: “But when Christ said: ‘Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s,’ those words, spoken on His last visit to the Temple, three days before His death, gave to the civil power, under the protection of conscience, a sacredness it had never enjoyed, and bounds it had never acknowledged; and they were the repudiation of absolutism and the inauguration of freedom.” It was not left to the nation but to the Church to secure its own rights in constant struggle with states that habitually fail to acknowledge their bounds:

For our Lord not only delivered the precept, but created the force to execute it. To maintain the necessary immunity in one supreme sphere, to reduce all political authority within defined limits, ceased to be an aspiration of patient reasoners, and was made the perpetual charge and care of the most energetic institution and the most universal association in the world.

Perhaps the best that could be hoped for is the American civic religion of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Capitalisms Good and Bad

Such difficulties concerning how we define nations, and what it means to be a citizen as viewed through the prism of nationality, remain underdeveloped in “A Statement of Principles.” The reason for this underdevelopment may be the perceived urgency of the unfolding tragedy that animates the movement: “We have watched with alarm as the traditional beliefs, institutions, and liberties underpinning life in the countries we love have been progressively undermined and overthrown.”

The crisis of traditional belief, institutions, and liberties is one universally acknowledged by the National Conservatives as well as their critics. Ahmari, as befitting the founder and editor of a magazine dedicated to challenging “the overclass that controls government, culture, and capital,” locates this crisis in the “material motives” of the bourgeoisie, who aimed and succeeded in toppling “an older order dominated by multinational empires and underpinned by the moral authority of a universal church.” The crises National Conservatives see unfolding within their nations is, in Ahmari’s estimation, the result of an unfolding historical dialectic in which those very nations played a leading role.

The critics who signed the “Open Letter” similarly posit that nations themselves had a leading part in the current crises, although they are careful to avoid the materialist reductionism of Ahmari:

The dissolution of national cultures was anticipated by the wiping out of local cultures, and the centralisation of power away from both local governments and civil society—notably churches, guilds, and other associations. It is nation-states as they are presently understood that have facilitated the ever-greater expansion of global capitalism and the unmediated technology that now threatens our social, civic, and spiritual lives.

The post-liberal answer to the Psalmist’s perennial question, “Why do the nations rage, and the peoples meditate on a vain thing?” (Psalm 2:1) seems to be in large part “global capitalism.” Pope St. John Paul II shared this concern: “If by ‘capitalism’ is meant a system in which freedom in the economic sector is not circumscribed within a strong juridical framework which places it at the service of human freedom in its totality,” then this is indeed a contributing factor to our present crisis. But this is not the only sense of “capitalism”; the pontiff observed a positive and constructive sense as well: “If by ‘capitalism’ is meant an economic system which recognizes the fundamental and positive role of business, the market, private property and the resulting responsibility for the means of production, as well as free human creativity in the economic sector,” then it is in this sense that we can justly state that “capitalism,” or better constructed simply the “free economy,” continues to lift millions out of poverty the world over. The NatCons recognize this sense when it is affirmed in “Principle 6—Free Enterprise” that: “We believe that an economy based on private property and free enterprise is best suited to promoting the prosperity of the nation and accords with traditions of individual liberty that are central to the Anglo-American political tradition.”

“A Statement of Principles” offers many caveats to this, emphasizing the need for a strong juridical framework and a “free enterprise” oriented to the national interest. Both of these caveats classical economists, such as Adam Smith, would have taken as a given. “Principle 7—Public Research,” which recommends the deployment of “large-scale public resources on scientific and technological research,” might clash with Smith’s “system of natural liberty,” but the statement does not divulge the actual details and mechanics of such policies.

Efforts such as this have been most generously mixed and least generously disastrous in the past. “Think Big” efforts of the Third National Government of New Zealand contributed to inflation and industrial troubles. Their failure indirectly set the stage for the economic liberalization undertaken by the Fourth Labour Government (dubbed Rogernomics after Finance Minister Roger Douglas) in the late 1980s and ’90s. These were similar to liberalization efforts under Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom during the same period that saw a worldwide breakdown of the postwar Keynesian consensus.

The Myth of Absolute Sovereignty

This notion that national policy should serve as a catalyst to economic development can be attributed to the centrality that “A Statement of Principles” gives the nation as locus of the historical development that has guaranteed the fruits of mature civilizations, including “patriotism and courage, honor and loyalty, religion and wisdom, congregation and family, man and woman, the sabbath and the sacred, and reason and justice.” This historical account is one Yoram Hazony has developed in his book The Virtue of Nationalism and extended in Conservatism: A Rediscovery. This just-so story has been criticized by many, including the short and incisive review of The Virtue of Nationalism featured in vol. 22, no. 2 of the Journal of Markets and Morality: “While the author claims to add clarity to political theory, the opposite is unfortunately the case. All political philosophies are made to fit a false dichotomy between nationalism, which affirms national sovereignty, and imperialism, which seeks to dismantle it.”

Both Ahmari and the drafters of the “Open Letter” take exception to this false dichotomy in their own ways. The “Open letter” states, “We agree with the signatories of the National Conservatism statement regarding the importance of the substantive goods that are today commonly threatened by globalisation. But these goods must be pursued at every level. There is no safeguard within nationalism that necessarily promotes them, no principle within internationalism that inherently opposes them.” The post-liberals rightly argue for the principle of subsidiarity in addressing the current crisis, and deftly observe:

The absolute sovereignty of the nation-state presented in the Statement of Principles is a modern myth, which traditional conservatives such as Edmund Burke questioned because, as with the French Revolution, it can lead to terror and tyranny. Burke’s alternative was a “cultural commonwealth” of peoples and nations covenanting with each other in the interests of mutual benefit and flourishing.

The principles of national independence and the rejection of imperialism and globalism, Principles 1 and 2 of “A Statement of Principles,” respectively, are not in themselves objectionable but can be a positive danger if removed and abstracted from the human person, society, and the common good. Lord Acton warned of precisely this in his essay “Nationality”: “Whenever a single definite object is made the supreme end of the State, be it the advantage of a class, the safety or the power of the country, the greatest happiness of the greatest number, or the support of any speculative idea, the State becomes for the time inevitably absolute.”

Nevertheless, the sincere, if unartfully grounded, rejection of imperialism in its historic as well as contemporary forms recommends these principles: “We reject imperialism in its various contemporary forms: We condemn the imperialism of China, Russia, and other authoritarian powers.”

These intra-conservative debates have only intensified, as exhibited by the 15 rounds of voting necessary for Republicans to elect a Speaker of the House.

Yet it is precisely this affirmation that Ahmari takes exception to in “The Return of Liberal Nationalism,” where he notes, “As non-liberal states such as Russia and China prosecute geographic claims along their peripheries, a supposed post-national liberal empire increasingly rallies to national flags.” The Russian invasion of Ukraine has been the facilitator, in Ahmari’s reading, for a renewed convergence of interests between liberalism and nationalism: “Liberalism and nationalism embraced for the first time since their estrangement in 1945.” This applies, according to Ahmari, to his estranged former allies the NatCons as well.

While Ahmari carefully notes that the Russian invasion constitutes a “calamity for the Ukrainian people,” he seems more alarmed by the coalition of liberals and nationalists that have come to their defense. His hostility to liberalism is so great that, in a since-deleted tweet, he claimed to be “at peace with a Chinese-led 21st century” because “late-liberal America is too dumb and decadent to last as a superpower.”

It is in opposition to such myopia that the “A Statement of Principles” has exercised its most salutary and responsible leadership. This commitment to genuine and legitimate national sovereignty, “a world of independent nations—each pursuing its own national interests and upholding national traditions that are its own,” may not be, as claimed, “the only alternative to universalist ideologies,” but it does provide concrete limits to the fetishization of arbitrary power.

If the confessionalization achieved in “A Statement of Principles” archives only the marginalization of those who would grandstand for the enemies of the liberal democratic West and humanity itself, it will have achieved much. The statement also addresses issues in a clearer and more coherent way than done previously, which also recommends it, even when mistaken on those issues.

Fear and Its Uses

These intra-conservative debates have only intensified, as exhibited by the 15 rounds of voting necessary for Republicans, the political home of much of the American conservative movement, to elect a Speaker of the House. The divisions in the caucus do not neatly correspond to the divisions between NatCons and their critics, however. They represent the anxieties concerning the future of the nation that motivate the movement. Edmund Burke, namesake of the institutional home of the NatCon movement, saw that “early and provident fear is the mother of safety,” but he also warned of its dangers: “No passion so effectively robs the mind of all its powers of acting and reasoning as fear.”

The post-liberal critics responsible for the “Open Letter” provide great insight in writing, “Political movements must be based on charity and friendship if they are to be in any way aligned with the Christian political tradition.” Here they echo the words of the beloved disciple: “There is no fear in love; but perfect love casteth out fear: because fear hath torment. He that feareth is not made perfect in love” (1 John 4:18).

While confessions can helpfully clarify, they also serve to calcify divisions. MacCulloch provides a moving illustration of this peril, recounting part of the history of the German city Bremen:

Bremen went over in the 1530s to the Lutheran cause against the opposition of its Catholic archbishop, but by 1561 the growth of Reformed belief among the merchant elite delivered control of the city into Reformed hands. … The aristocratic canons of the Cathedral, however, remained staunch Lutherans: the resulting clash between city and Cathedral authorities closed the doors of the building to worshippers. For an astonishing seventy-seven years after 1561, the vast church, locked and silent, cast its shadow over the busy life of the two principal city markets, the medieval treasures of its interior preserved unused though undefaced.

A divided conservative movement is a movement unable to rise to the challenges of the crises of our time. Without responsible leadership we will witness further disintegration into vacuous and ineffectual right-wing populism fueled only by the basest resentments.

The confessionalization of National Conservatism has served to clarify, and one hopes those clarifications will be the basis for further dialog and not the pretext for the ossification of division. While the concerns animating National Conservatism are real, its reduction of today’s problems and tomorrow’s solutions to issues of nationality, if stubbornly held, will lead to stalemate and irrelevance. A constructive political vision must, as Lord Acton concluded, be based on the human person and dedicated to human freedom, for “liberty alone demands for its realisation the limitation of the public authority, for liberty is the only object which benefits all alike, and provokes no sincere opposition.” The Psalmist tells us that often “the kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers take counsel together, against the Lord” (Psalm 2:2). It is not by the nation alone but only through the organic development of all spheres of life—according to their own principles—that God’s order can be restored in these troubled times.