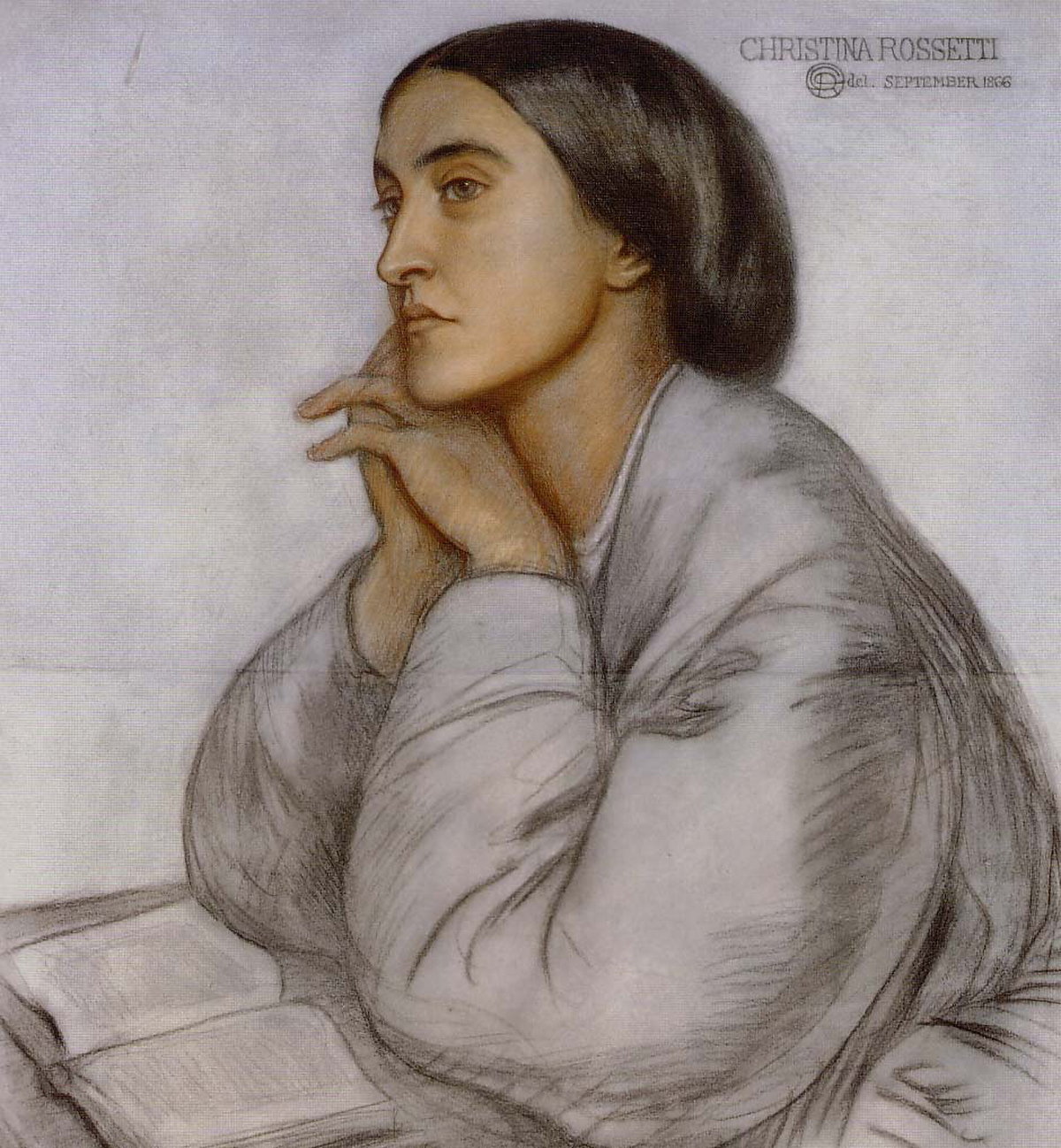

As the Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt was working on The Light of the World (1851–1854), his portrayal of Jesus knocking on a vine-covered door, he found perhaps an unlikely model for the face of Christ: Christina Rossetti, the sister of his fellow Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel. Hunt admired her “gravity and sweetness of expression,” and thus thought this young woman perfect to convey the Savior’s gentle persistence on the door of the human heart. Indeed, “gravity and sweetness” would mark Christina Rossetti’s own faith, as well as her poetry.

Too often it’s assumed that an artist must have a tortured life freed from moral norms in order to produce great art. Christina Rossetti lived a life of fidelity and self-sacrifice, and her poetry continues to entrance with her vivid Christian imagery and unique synthesis of “gravity and sweetness.”

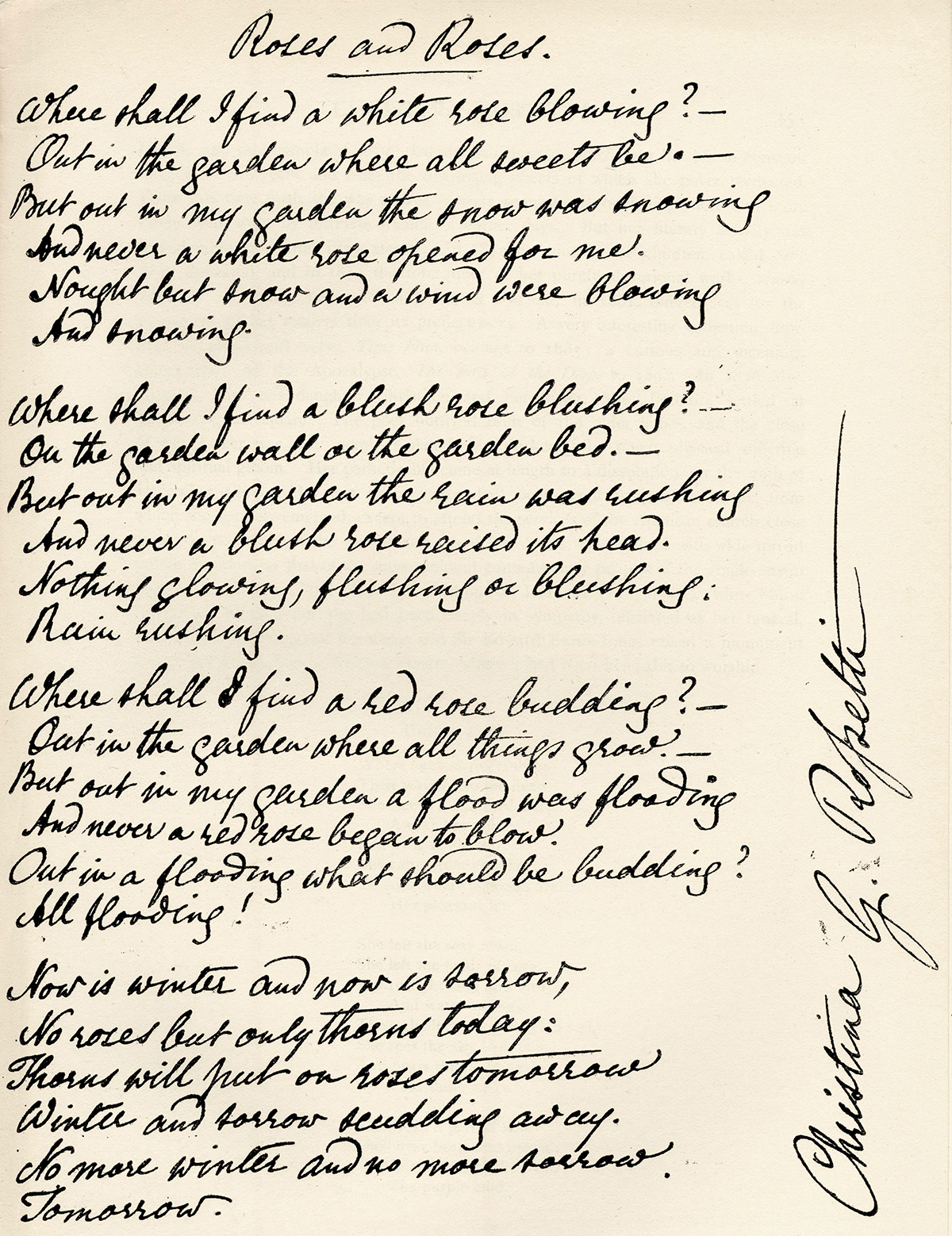

Rossetti’s poems entrance by their vibrant imagery, depth of feeling, and fine craftsmanship. Her sonnets are as moving in their melancholic love as Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s in their ecstatic fulfilled love. She was skilled at dramatic verse, inhabiting different speakers, while also penning personal, powerfully intimate, spiritual poems: Goblin Market, “Up-hill,” “Song” (“When I am dead, my dearest”), “A Birthday,” “A Better Resurrection,” and many beloved sonnets such as “Remember me when I am gone away,” “I lov’d you first: but afterwards your love,” and “Many in aftertimes will say of you.” Several of her Christmas carols have entered English hymnody, most famously “In the Bleak Midwinter” but also “Love Came Down at Christmas.”

While the poet lived what appeared to be a retired life of writing poetry and letters to friends and family, she was born in the midst of the tectonic shifts and debates and personalities of England’s Victorian Age. Rev. John Keble’s Assize sermon “National Apostasy” on July 14, 1833, sparked the flame that became the Oxford Movement. Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species would enter the world stage in 1859. The industrial age was well underway, as were its critics: Charles Dickens was writing his greatest works, and the great William Wordsworth passed away in 1850, when Rossetti was 20 years old. Elizabeth Barrett Browning published Sonnets from the Portuguese that same year. Emily Dickinson and the Brontë sisters were contemporaries, and it was the age of Edward Lear, Robert Louis Stevenson, and John Ruskin. Her life roughly spanned the reign of Queen Victoria, crowned when Rossetti was seven years old; the queen would live only seven years beyond the year of Rossetti’s own death in 1894 at age 64. She became a well-beloved poet, and when Tennyson died in 1892, there were whisperings that she ought to be the nation’s new poet laureate (much to her chagrin; her friend Ford Madox Ford commented that “the idea of such a position of eminence filled her with real horror”).

Rossetti’s poems entrance by their vibrant imagery, depth of feeling, and fine craftsmanship.

Rossetti’s reputation as a poet has only grown since her lifetime; she is now regarded as one of the greatest of Victorian England’s poets. Her life and work were certainly shaped by her experience as a woman in the Victorian Age, and feminist criticism has enjoyed speculating on her love affairs (she turned down two proposals of marriage) and searching for subversive qualities in her art. But underlying Rossetti’s life and work is a deeper and underappreciated subversion: her deep love of the Scriptures, her Anglo-Catholic faith, and, above all, her love affair with Christ.

Among the Exiles

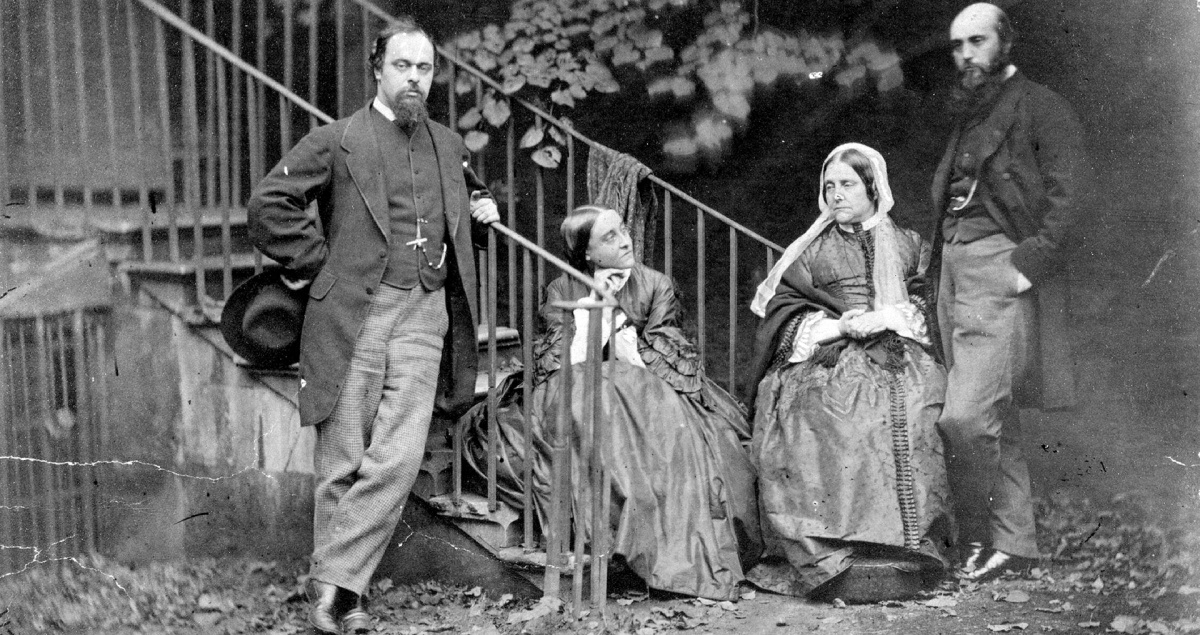

On December 5, 1830, Christina Georgina Rossetti was born in London to Gabriele Rossetti, a lapsed Roman Catholic and Dante scholar in exile from Italy, and the half-Italian, half-English governess Frances Polidori Rossetti. Rossetti and her elder siblings—Maria Francesca, William Michael, and Gabriel Dante—were educated at home by their mother; they were immersed in the Bible and literature, as well as the Italian language. Their home became a haven for Italian expatriates, the wars for unification driving them from their homeland. She grew up reading the Romantics, as well as such tales as The Arabian Nights. Later she would also become familiar with Augustine’s Confessions and Thomas à Kempis’s Imitation of Christ and study Plato, Dante, Aquinas, George Herbert, and William Blake, as well as contemporary theologians John Keble, John Henry Newman, Isaac Williams, and Edward Pusey.

Childhood visits to her maternal grandfather’s house outside the city would also play a formative role for the budding poet: “If any one thing schooled me in the direction of poetry,” she wrote in a letter to the poet and critic Edmund Gosse in 1884, “it was perhaps the delightful idle liberty to prowl all alone about my grandfather’s cottage-grounds some thirty miles from London.” Throughout her life she would maintain friendships with a diverse array of writers and artists—such as the atheist poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, Lewis Carroll, the adventurous William Holman Hunt, the pious Coventry Patmore and his wife, the novelist Hall Caine, painter and illustrator Arthur Hughes, and the families of William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones—but also with the unnamed neighbors and fellow parishioners at her church. Charles Cayley, a translator of Dante’s Commedia and a family friend, also became a dear and intimate friend. Though she turned down his proposal of marriage because of his agnostic faith (many of her love sonnets, those written in English and those in Italian, were most likely written with him in mind), they remained close friends until his death.

The Oxford Movement

Mrs. Rossetti and her two sisters, devout evangelical Anglicans, became committed Anglo-Catholics when the Oxford Movement came to London. One of the movement’s most prominent preachers, William Dodsworth, was vicar of the Rossettis’ parish church, Christ Church, Albany Street, St. Pancras, until 1851. This “Catholic revival” was a phenomenon that covered more than a return to ritual. Rather, it was a spiritual revival indeed; John Henry Newman marked its beginning with the aforementioned Rev. Keble’s “National Apostasy” sermon in 1833. (Newman would publish the first of the movement’s 90 Tracts for the Times later that same year.) Keble excoriated his fellow Englishmen for spiritual lukewarmness and religious indifference. He called for a spiritual and moral awakening, and it was in this context that the Tractarians took on a project of renewal through ressourcement: They sought not only to preserve “the apostolical succession and the integrity of the Prayer Book” that bound together the Church of England’s spiritual life but also to recover some of the richness of the church that had been swept away during and after the Protestant Reformation. These years saw a renewed emphasis on everyday holy living, the founding of Anglican religious orders for men and women, and the publication of 48 volumes of translations from the Church Fathers, the Library of the Fathers, as well as the volume Hymns Ancient and Modern.

Rossetti and her sister, Maria, joined their mother and aunts wholeheartedly in the Catholic revival. In fact, Maria would join one of the Anglican sisterhoods in London in 1874. Rossetti regularly went to confession, took communion twice a week, faithfully attended church services, observed morning and evening prayer, and with the ladies of the household took part in charitable work, such as making scrapbooks for children in the hospital. And though Rossetti herself did not become a religious sister like Maria, for 10 years she volunteered at St. Mary Magdalene Home on Highgate Hill, where “fallen women”—that is, former prostitutes, abandoned wives, or unwed mothers—could receive help and shelter. (She would advocate raising the age of consent after her experiences at Highgate.) She also would spend time at hospitals associated with Maria’s All Saints Sisterhood. And always she tended to her mother, whom she held in the highest regard and deepest affection. As she would write in a sonnet when her mother turned 80:

To my first Love, my Mother, on whose knee

I learnt love lore that is not troublesome:

Whose service is my special dignity,

And she my lode star while I go and come.

The Church of England remained Rossetti’s mother church. Though Newman and others, such as the Rossettis’ former pastor William Dodsworth, would ultimately join the Roman Catholic Church, Rossetti herself never seemed tempted by the Tiber. (She twice turned away the painter and former Pre-Raphaelite James Collinson because of his conversion Rome-wards, though some speculate the rejection was due more to his lackluster personality.) She was content to remain in the church of her youth, while also recognizing the brotherhood of those in the Roman communion. Her brother William wrote that “she considered them to be living branches of the True Vine, authentic members of the Church of Christ.” Indeed, when Cardinal Newman passed away, she honored him with a sonnet:

O weary Champion of the Cross, lie still:

Sleep thou at length the all-embracing sleep:

Long was thy sowing day, rest now and reap:

Thy fast was long, feast now thy spirit’s fill.

Yea, take thy fill of love, because thy will

Chose love not in the shallows but the deep.

Anglo-Catholicism sought to balance the picture by emphasizing the reality of mystery, symbol, and sacramentality—indeed, the poetry of Christianity.

The Poetry of Faith

In a time of sometimes over-rational defenses of the Christian faith, Anglo-Catholicism sought to balance the picture by emphasizing the reality of mystery, symbol, and sacramentality—indeed, the poetry of Christianity. The Tractarians saw creation as pointing toward the glory of God; everything in creation was weighted with the reality that Christ had loved the world into existence. As Rossetti scholar Emma Mason has put it, Rossetti and the Tractarians agreed with the Church Fathers that “every detail carried in it the mark or stamp of God, each stone, ant, bee, and mosquito revealing his wisdom and collectively inviting the onlooker into faith.” The natural world, too, provided a way to “see” the unseen by way of analogy, in which “material phenomena are both the types and the instruments of real things unseen.” Newman himself, in his classic Apologia Pro Vita Sua, argued that Christians have a “duty” to have a “poetical view of things”; the poet then can provide a space for contemplation of the divine through attention to the natural world.

In an essay entitled “Sacred Poetry,” Rev. Keble, himself the chair of poetry at Oxford and author of a collection of verse on the Christian liturgical year, enjoined the religious poet to follow the example of plain chant: to avoid extravagant imagery in favor of “grave simple, sustained melodies,” “fervent, yet sober; aweful, but engaging; neither wild and passionate, nor light and airy,” yet filled with “noble simplicity and confidence” in God’s truth. Indeed, this captures much of the spirit of Rossetti’s poetry: there is a disarming simplicity and sincerity in her poems, as well as a keen awareness of the symbols inherent in the everyday. In his Lectures on Poetry, Keble noted that while “Poetry lends Religion her wealth of symbols,” religion “restores these again to Poetry, clothed with so splendid a radiance that they appear to be no longer merely symbols, but to partake (I might almost say) of the nature of sacraments”—that is, poetry enables one to see “sacramental symbols,” everywhere, just “as the first Christians saw around them at all times and in all places.”

In this way the Catholic Revival paralleled the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (P.R.B.), the artistic compact Rossetti’s brother Dante Gabriel spearheaded and that sought to achieve a kind of secular sacramentality, a reaction to an industrial, disenchanting age. Though not a Pre-Raphaelite herself, Rossetti became associated with the movement through her brother. She served as a model for the Virgin Mary in Dante Gabriel’s paintings The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1848–49) and his painting of the Annunciation, Ecce Ancilla Domini! (1849–50). Some of her earliest and most well-beloved poems were first published in The Germ, the P.R.B.’s short-lived literary and artistic periodical.

Rossetti’s poetry was not “issue-based”; her nursery rhymes, however, were more didactic, as befitting children’s verse. Her collection Sing-Song includes rhymes about country and household, but also about loving one’s neighbor (including the creatures of the natural world) and verse on heavier subjects such as the death of birds and babies, all with a sensitive eye toward the child’s world.

Given her respect for God’s image in humankind and in the goodness of creation, certain causes she espoused nevertheless made their way into her poetry: she contributed a short piece of verse whose topic was kindness to animals, and which benefited the Anti-Vivisectionist Society. Another poem, “The Iniquity of the Fathers upon the Children,” may have been prompted by her experience at Highgate: the speaker, an illegitimately conceived daughter, reproaches the father who abandoned her and forced her mother to live a lie:

Why did he set his snare

To catch at unaware

My Mother’s foolish youth;

Load me with shame that’s hers,

And her with something worse,

A lifelong lie for truth?

In “A Royal Princess,” the princess of the title comes to recognize that she owes her comfortable position to the exploitation of others: “Once it came into my heart and whelmed me like a flood, / That these too are men and women, human flesh and blood.”

The Bible was intimately tied with the book of nature in her art: as the critic Dinah Roe notes, “It could be said that Rossetti’s poetry is in fact constituted by exegesis. She refers to the Bible, either by quotation or allusion, in nearly every poem.” Historian Timothy Larsen has highlighted her rigorous defense of truth and her challenge to comfortable Christianity in her devotional work and scriptural commentary, observing that she “pronounces all bad theology as a violation of the command not to take the Lord’s name in vain.” Hers was no milquetoast faith.

Rossetti possessed what G.K. Chesterton called “the old humility”: She was “undoubting about the truth,” firm in her faith in Christ and His Church, but doubtful of herself. Her poetry, letters, and devotional writing evince a consistent call to self-examination, to continual conversion of heart. Memento mori is a key theme of her poetry. She was keenly aware of the reality of a final accounting and that what we do in this life will matter for the next.

One of her stanzas from her poem “The Lowest Place” is inscribed at her burial place in Highgate Cemetery:

Give me the lowest place: or if for me

That lowest place too high, make one more low

Where I may sit and see

My God and love Thee so.

The Call to Obedience

The sensuousness of her imagery—particularly in the celebrated narrative poem Goblin Market—and the pathos of her sonnets continue to make Rossetti popular, but less enchanting to the modern mind is the unmistakable aroma of piety and duty in her work. This is a poet who felt the tension of the intoxicating fruits of the world and the call to obedience to Jesus Christ. Compared with her oft-intemperately passionate brother Dante Gabriel, Christina can seem like a stick-in-the-mud on a first, shallow glance. And, indeed, Christina wrote during a time when Romanticism was ascendant: the Age of Johnson, an era that emphasized reason, balance, and order in art, was over. This was an era of the elevation of “passion” as not something that one experiences (or suffers) but as nearly itself a virtue: To be “carried away” by one’s feelings, or passions, was a good thing. Indeed, it is a hard thing indeed to dramatize the actual battle that transpires in a soul that is striving for mastery of one’s emotions; it is harder by far to master great passion than to be carried away by it, but the latter is what excites, well, our passions. It is more exciting to read of the wife who gallops away on the instant with her lover than the Anne Eliots or the nurse or nun—or poet—who spends years tending to sick children and neighbors. Perhaps the genius of Christina Rossetti’s work is that it dramatizes the journey of the soul that strives to do good and to love neighbor and God well.

For example, the use of the word sweet in her work illuminates the tension and paradox of the affirmative and the negative way: loving the world and yet rejecting it for the sake of Christ; savoring the short-lived sweet things of this life and the longing for the undying sweetness of eternity.

Lizzie’s sacrificial love for her sister Laura in Goblin Market, a sweeter fruit by far than any of the luscious goblin fruit that finally brings death, becomes an image of the new life brought from death, reflected in the springtime but also imaged in the love of Christ: a real and powerful reality across Rossetti’s poems.

Sinister goblin men are not the only ones who offer sweets in Rossetti’s poems. In “I Will Lift Up Mine Eyes Unto the Hills,” the speaker longs for the “sunshine” of “the everlasting hills,” in the midst of the weariness of this world:

I am pale with sick desire,

For my heart is far away

From this world’s fitful fire

And this world’s waning day …

Each stanza begins with a lament that is then answered by the Saints:

In a dream it overleaps

A world of tedious ills

To where the sunshine sleeps

On the everlasting hills.—

Say the Saints: There Angels ease us

Glorified and white.

They say: We rest in Jesus,

Where is not day or night.

In the final stanza, Jesus, too, speaks—and He is the one who offers sweets.

Say the Saints: His pleasures please us

Before God and the Lamb.

Come and taste My sweets, saith Jesus:

Be with Me where I am.

Here the offer of sweets is an invitation and a gift rather than an advertisement for merchandise. And in “the heavenly day,” nothing can rot or spoil, unlike the sweets—the flowers, the fruits, the friendships—of earthly life. Whereas, in “Paradise,” the fruit of the Tree of Life is “Sweeter than honey to the taste, / And balm indeed.”

“Advent,” a poem that makes use of the parable of the seven virgins waiting with their lamps for the Messiah, compares the sweetness of Christ with honey. The waiting souls on earth discuss:

“Friends watch us who have touched the goal.”

“They urge us, come up higher.”

“With them shall rest our waysore feet,

With them is built our home,

With Christ.” “They sweet, but He most sweet,

Sweeter than honeycomb.”

Here the sweetness of reprised friendship is anticipated in the heavenly realm: Christ is the home wherein even the friends will be reunited, but Christ himself is “most sweet.”

But in the meantime, the earthly life, though it does contain sweet summer weather and the “sweetest blossoms die” (“Sweet Death”), is full of toil, an uphill climb. And yet to know that good things wait, though “long deferred,” and rest that we cannot conceive is “comfort [to the] travel-sore and weak” (“Up-Hill”).

But in Goblin Market, the sweets of the goblin men are not simply harmless, evanescent pleasures. They are rather akin to the wooings of “The World”:

By day she wooes me to the outer air,

Ripe fruits, sweet flowers, and full satiety:

But through the night, a beast she grins at me,

A very monster void of love and prayer.

“The Love of Christ Which Passeth Knowledge” builds and extends the image of Christ as “most sweet,” to the love that he bears for lost souls, just as Lizzie herself is sweeter than honey to Laura, partly because Lizzie loves her. It is not knowledge but love that finally saves Laura.

In the beginning of the poem, Christ speaks of his longsuffering love:

I bore with thee long weary days and nights,

Through many pangs of heart, through many tears;

I bore with thee, thy hardness, coldness, slights,

For three and thirty years.

Who else had dared for thee what I have dared?

I plunged the depth most deep from bliss above;

I not My flesh, I not My spirit spared:

Give thou Me love for love.

In the third stanza of “The Love of Christ,” He calls the souls, “Much sweeter thou than honey to My mouth.” The image of the sweet-as-honey loved one is turned back upon the human being.

Rossetti’s piety would scandalize later critics and writers, who viewed her faith as morbid, even repulsive.

This is how Rossetti sees the tension of this life finally resolved: the sweets of this life—fruit, honey, friends—are foretastes of the sweet love of Christ that is greater by far than both wintertime and evil goblin fruits. Indeed, our loves in this life are made sweeter, rather than spoiled, when they are experienced in light of the ultimate Love.

Piety, then, is rooted in love and hence rendered a sweet duty, while at the same time a painful trial, because of the rightful longing we experience for complete and perfect rest, and true and lasting communion.

Winter to Spring

In 1872, Scribner’s Monthly published Rossetti’s “A Christmas Carol”—more commonly known today by its first line, “In the bleak mid-winter” (accompanied by either Gustav Holst’s 1909 musical setting or Harold Darke’s of 1911). Music continues to be written for her poems to this day.

A few years later, the Irish writer Katharine Tynan Hinkson visited the esteemed poet at her home in Torrington Square and found, to her surprise, not a saint in “trailing robes of soft, beautifully coloured material,” but rather a middle-aged spinster “wearing short serviceable skirts of an iron grey tweed and stout boots.” But the poet herself was hardly as dour as her garment: “I wrote such melancholy things when I was young,” she told Hinkson, “that I am obliged to be unusually cheerful, not to say robust, in my old age.”

Like Mary in “bleak mid-winter,” celebrating new life in the “stable-place” where for the “Lord God Almighty,” a “breastful of milk / And a mangerful of hay” is enough, Rossetti found great sweetness amid her quiet life. She was still writing poetry regularly and would publish a 500-page meditation on St. John’s Apocalypse, The Face of the Deep, while tending to her mother and two aunts. Though she traveled little and spent much of her life in garden-less London houses, she noticed and praised even the smallest of creatures, including a sea mouse given her by her friend Charles Cayley and her pet cats Muff and Carrots.

When her brother William’s baby son Michael was at death’s door, Rossetti asked to be allowed to baptize him. William consented, and “she performed the rite unwitnessed, and I doubt whether any act of her life yielded her more heartfelt satisfaction.” Such an act bespeaks her love and attention toward the least of these. She knew the beauty of this life, but she also knew that it paled in comparison to the beauty of Christ, Love Himself.

When she lay dying of breast cancer, her priest visited her once a week to administer the Eucharist. She was still moving her lips in prayer moments before passing into eternal springtime.

Rossetti’s piety would scandalize later critics and writers, who viewed her faith as morbid, even repulsive. And yet, with cheerful vigor, wit, and determination, Rossetti evinced true joy in her life, not in spite of but because of the beauty of Christ and the reflection of that beauty in creation, and in every human being, no matter how marginal or vulnerable.

Christina Rossetti is a rare poet: the strength of her quiet faith, her self-sacrificial love, and her keen spiritual perception invigorate her art. As in the best of the Anglo-Catholic tradition, goodness and truth meet in her life and work. She demonstrates that a life of ordered, faithful loves, undergirded by the conviction that every human soul is made for beauty, is no stranger to making great art.