Unless we live in the night when all cows are black, we occupy a multihued world whose contours become more distinct as light intensifies. Our tendency to simplify brings us deeper into the shadows, and perhaps one of our greatest oversimplifications is the uncritical faith in progress, and one of the unfortunate side effects of this tendency is that we too easily identify those on the right side of it and those on the wrong side.

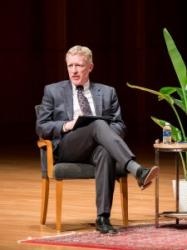

The 19th century reformer believed that “society” had to intervene early in the educational process of its youngest citizens or pay a steep price later. He also saw parents as an impediment to the “common end” of inculcating the Protestant virtues. Ironically, his totalizing vision resulted in the eradication of religious values altogether.

Americans possess the itch for progress deeply in their marrow, with scant attention to what—or who—gets left behind. There are different ways of dealing with that problem: one would involve indifference, with a concomitant accusation that anything left behind wasn’t worth preserving anyway, while another would involve coercive efforts to force the past and its defenders to keep pace. One of the main mechanisms of such compulsion is a system of education. Justice William O. Douglas provided a good example of this in Wisconsin v. Yoder, objecting to Amish people’s opting out of the system of public education:

It is the future of the student, not the future of the parents, that is imperiled by today's decision. If a parent keeps his child out of school beyond the grade school, then the child will be forever barred from entry into the new and amazing world of diversity that we have today. … If he is harnessed to the Amish way of life by those in authority over him and if his education is truncated, his entire life may be stunted and deformed. [emphasis added.]

The obsession with progress tracks what David Corey has called “the politics of unitary vision.” In other words, human beings experience stark divisions; if those divisions are consequential enough that they find themselves unable to live with them, they resort to one of three strategies: they separate from one another (the secessionist strategy), minimize the differences (the pluralist strategy), or permit the dominant faction to subjugate weaker ones (the unitary strategy). The latter can be accomplished through either force or milder forms of compulsion, such as mandated and compulsory systems of education. In contemporary America, we see all three strategies at work, but progressives most actively pursue the unitary strategy and accomplish it through control of the schools (both the public schools and the universities).

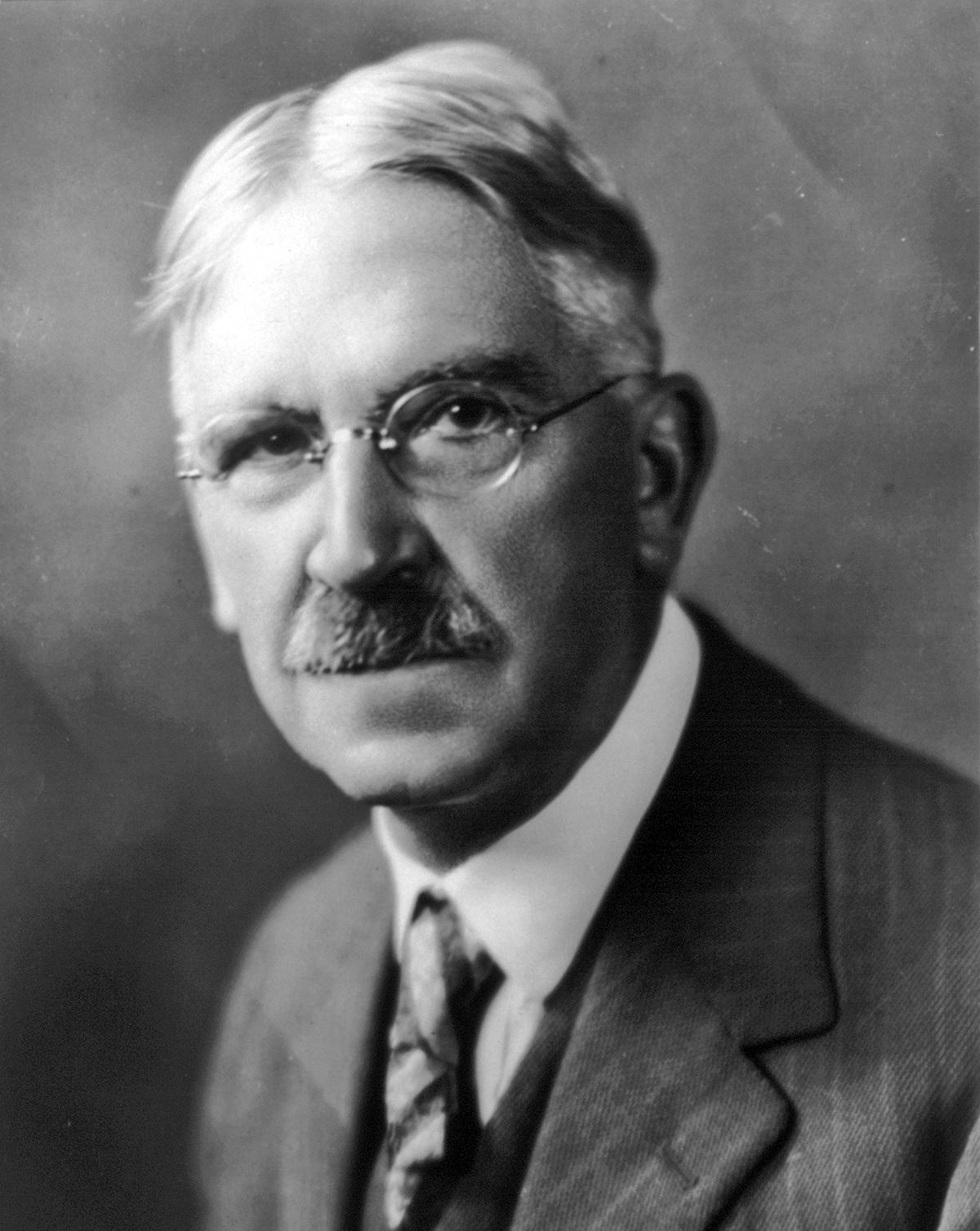

Horace Mann, the 19th-century educational reformer, provided America with a fine “unitary” example. Mann operated at a crossroads moment in American history: the development of “the American system,” with its emphasis on linking the continent together via roads and canals; Jacksonian democracy, with its egalitarian impulses and increased atomization of the population, which also, by expanding the franchise, altered the idea of citizenship; an increasingly intemperate citizenry; a nation struggling through its sectional crisis fueled by debates over slavery; the age of transcendentalism and reform; mass immigration, especially that of Catholics; and the emergence of an industrial economy with its demands on the formation of “workers” who were no longer independent economic actors.

Coming from an uneducated background, Mann was, until his admission to Brown University at the age of 20, an autodidact and in many ways embodied the reformist spirit of the age, including its objections to intemperance and, more importantly, slavery. Stamped by the severe Calvinism of his youth, Mann as a teenager began to follow the more unitarian path so many had blazed before him. Hating the substance of his religious upbringing, he maintained its form and spirit. As a political Whig, Mann followed the policies that focused on national unity. In that sense, Mann was very much an advocate for a politics of unitary vision, and while he didn’t necessarily draw his ideas from classical sources, a detour into their thought will help illuminate his.

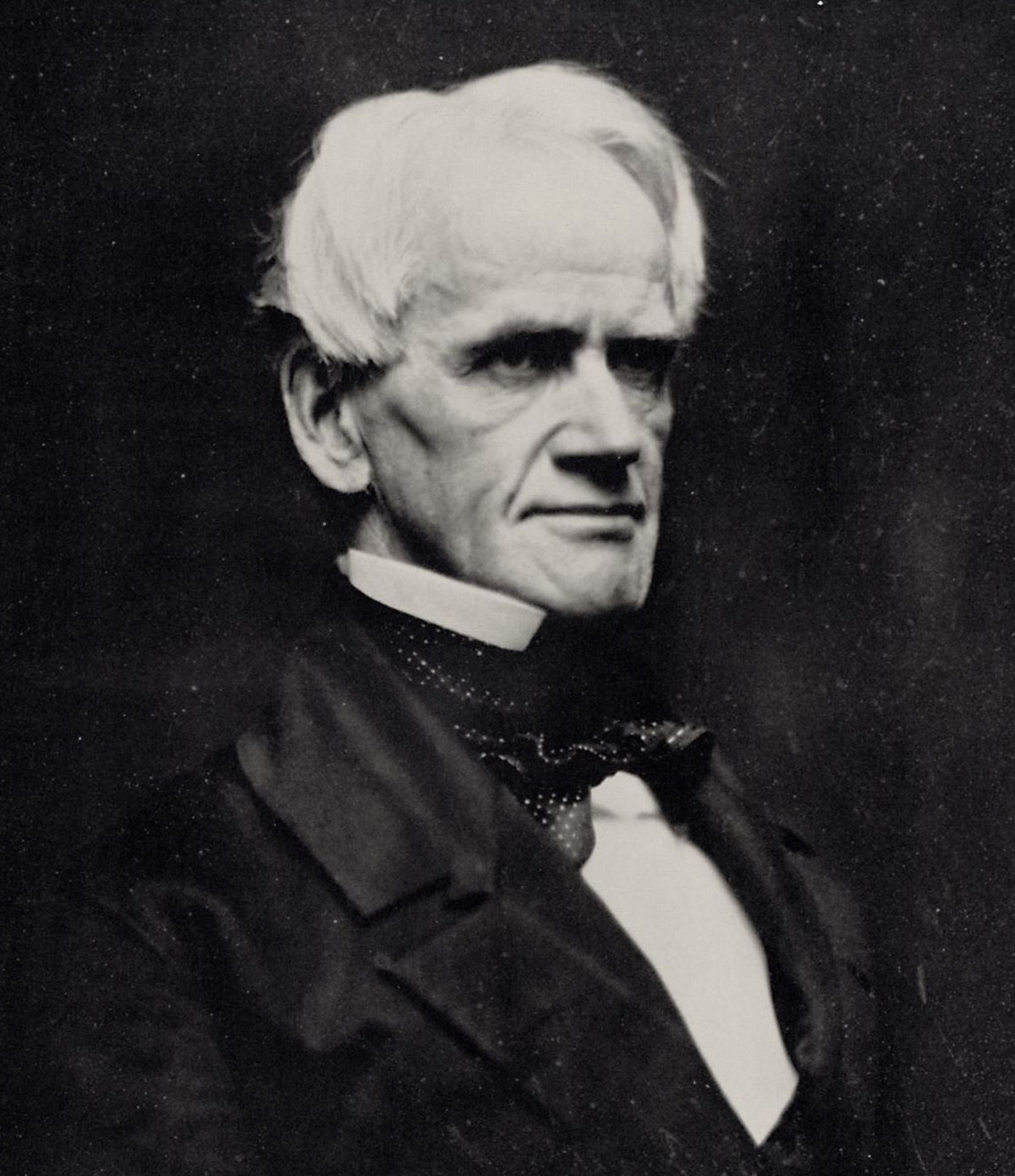

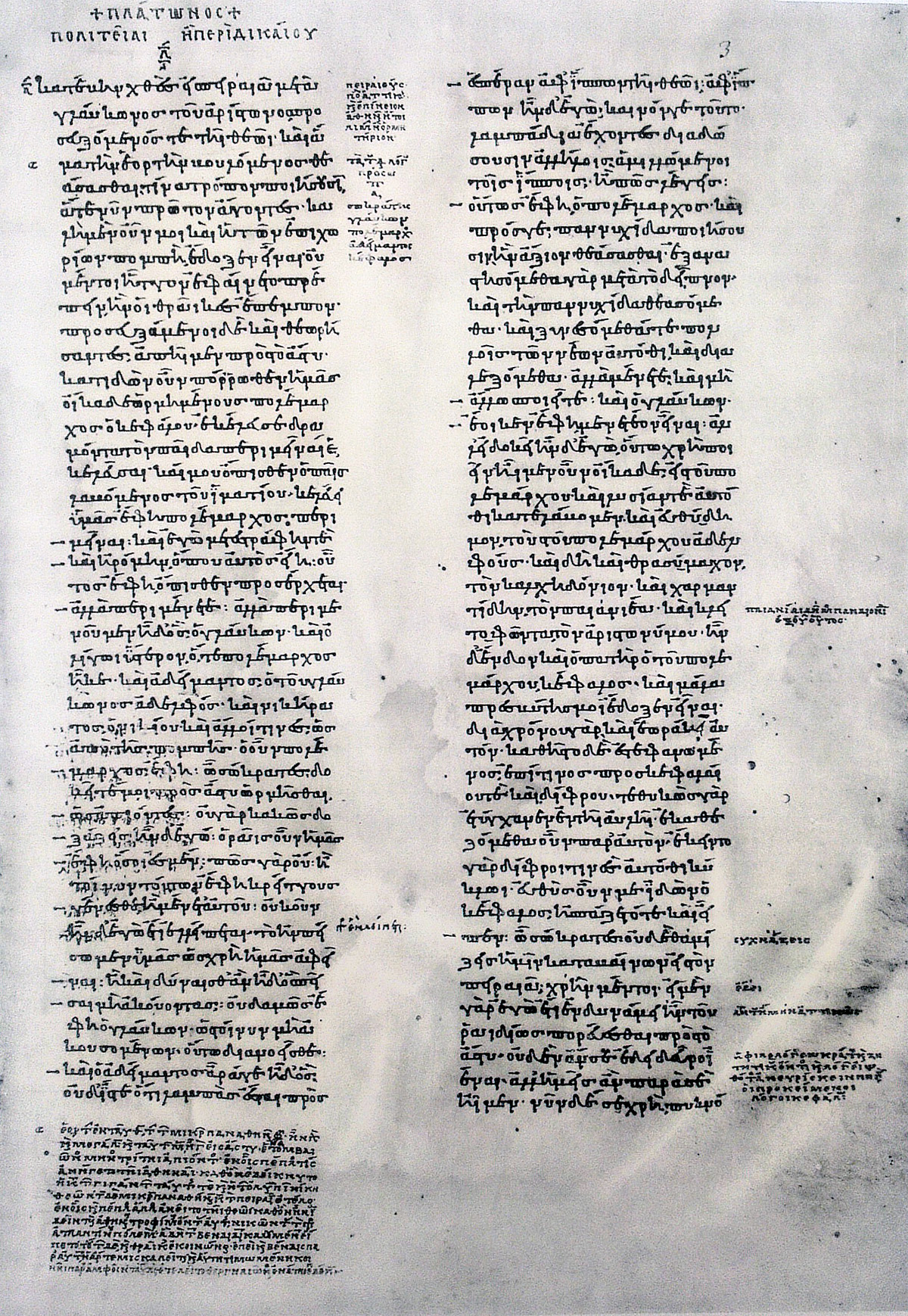

Plato and Aristotle

In his Republic, Plato elevated the well-being of the whole over the parts, ushering in the idea that a nontribal society could still hold together without shared blood lines. Once the ties of kinship were weakened, some other principle had to take its place. Plato never advocated any educational program as that instituted in Sparta, but neither was he indifferent to its advantages. Self-interest, particular loyalties, competing stories, and varieties of parenting meant that political order was constantly on a vertiginous edge threatening to collapse.

In his dialogue The Laws (Book VII), he carefully outlined a system of education that served justice by promoting unity. This system “can be treated more suitably by way of precept and exhortation than by legislation.” The essential problem was that “in the private life of the family many trivial things are apt to be done which escape general notice,” producing “in the citizens a multiplicity of contradictory tendencies” that are “bad for a state.” Like trees that we brace when they are saplings, young people must be properly staked so they grow to be straight and true, and this must take place “when growth occurs rapidly.”

Unless private affairs in a State are rightly managed, it is vain to suppose that any stable code of laws can exist for public affairs; and when he perceives this, the individual citizen may of himself adopt as laws the rules we have now stated, and, by so doing and thus ordering aright both his household and his State, may achieve happiness.

As a political Whig, Mann followed the policies that focused on national unity.

Plato began this comprehensive system of education in utero and continued it through infancy and childhood. Because of the force of habit, it is in infancy that the whole character is most effectually determined, meaning every adult interaction with children had to be regulated with reference to how the interactions cultivated the virtues that served the well-being of the state. When Clinias asked “how the authority of the state [can] be brought to bear on human creatures that are not yet capable of speech,” the Athenian Stranger replied that he was referring to “the unwritten law,” or “the whole of the body of such regulations” that are “the mortises of a constitution”—similar to what Tocqueville meant by mores. The laws are simply the brickwork of the polity, held together by the habits of the heart that operate as the concrete that holds it all together; so any system of education must attend to the cement even more than to the laws, with the proper blending of elements taking place at the beginning. The Stranger insisted that regulating the stories we tell, the behaviors we allow, the music we encourage the young to listen to, the manners we inculcate, the marriages we arrange, the games we play, the work we assign, patterns of sleep, even the amount of alcohol we drink, all helped stabilize and unify the state.

For when the program of games is prescribed and secures that the same children always play the same games and delight in the same toys in the same way and under the same conditions, it allows the real and serious laws also to remain undisturbed; but when these games vary and suffer innovations, amongst other constant alterations the children are always shifting their fancy from one game to another, so that neither in respect of their own bodily gestures nor in respect of their equipment have they any fixed and acknowledged standard of propriety and impropriety; but the man they hold in special honor is he who is always innovating or introducing some novel device in the matter of form or color or something of the sort; whereas it would be perfectly true to say that a State can have no worse pest than a man of that description, since he privily alters the characters of the young, and causes them to contemn what is old and esteem what is new. And I repeat again that there is no greater mischief a State can suffer than such a dictum and doctrine.

Having lived through the constant rise and fall of Athenian governments, Plato’s aversion to “change,” which is always “highly perilous,” resulted in strict rule of children’s lives. “Children who innovate in their games grow up into men different from their fathers; and being thus different themselves, they seek a different mode of life, and having sought this, they come to desire other institutions and law.” He did allow for change in “what is bad,” but only the wise statesman was capable of making such determinations.

The good society required a lawgiver preeminent in wisdom to discern the good and instantiate that wisdom into laws. When the laws are good, obedience to the law results in virtue. “The virtuous man is he who passes through life consistently obeying the written rules of the lawgiver, as given in his legislation, approbation and disapprobation.”

Likewise, Aristotle began Book VIII of the Politics by insisting that “the legislator should direct his attention above all to the education of the youth.” A well-organized state insisted that “education should be one and the same for all, and that it should be public, not private—as it is at present, when everyone looks after his own children separately, and gives them separate instruction of the sort which he thinks best.” Unlike Plato, Aristotle referred such education to “things which are of common interest,” thus allowing for some individuating, but also insisted that no citizen “belongs to himself”; rather, “all belong to the state” for each are a part of it, “and the care of each part is inseparable from the care of the whole.”

Unlike Plato’s Stranger, Aristotle dealt with some knotty political problems, noting that there will be “much disagreement” about what this education should look like, in part because we are “by no means agreed on the things to be taught.” “The existing practice is perplexing; no one knows on what principle we should proceed.” Disagreeing about the purposes of education presents enough difficulties, but we also disagree about the means. Drawing a sharp distinction between the liberal and the servile arts, Aristotle warned against preparing our best and brightest for any kind “of paid employment” that must necessarily “absorb and degrade the mind.” For the general population he recommended an education “partly of a liberal and partly of an illiberal character,” the distinction hinging on whether the education served an extrinsic purpose. Therefore, “the first principle of action is leisure,” since leisure (sharply distinguished from “amusement”) alone allows us to exercise our capacities to the fullest for no other purpose than to enjoy them.

Mann and the Problem of Democracy

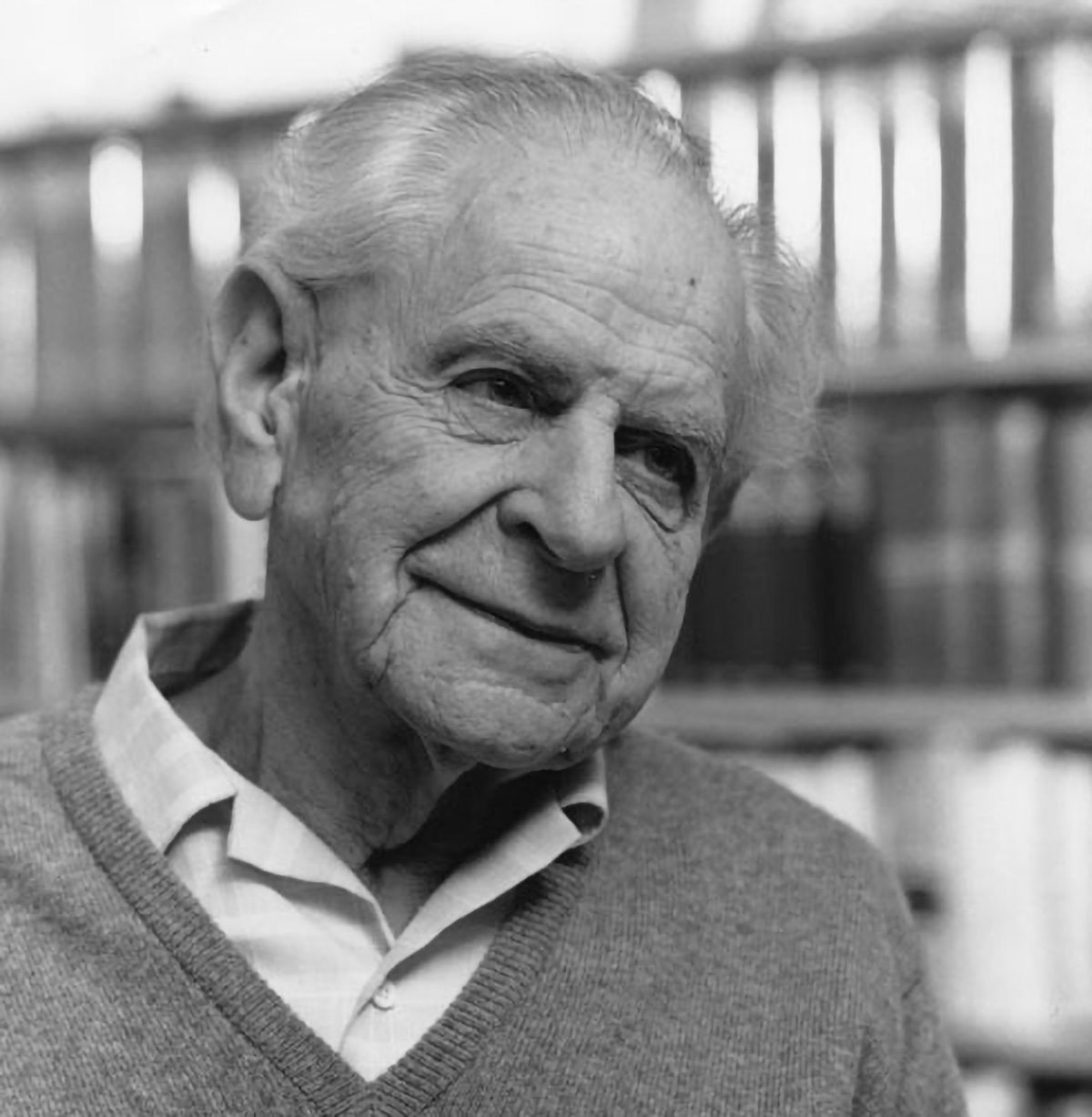

Karl Popper in his The Open Society and Its Enemies designated Plato as a forerunner of modern totalitarianism, and whatever the merits of that claim it speaks to the uncomfortable fit between Plato’s writings and modern liberal democracy. Plato’s world was hierarchically arranged and nonegalitarian, while liberal democracies are deeply suspicious of hierarchies. Balancing the demands of public education and a democratic ethos against the American emphasis on freedom and individual conscience became a central problem for Mann.

Mann’s approach combines this old classical way of thinking with a denuded Calvinist theology and a commitment to the promises of American democratic liberalism, this despite, or maybe because of, his concern about democratic excesses. Permanently stamped by Calvinism, Mann advocated for an education that in substance mirrored Max Weber’s portrait of Franklin as the conduit for the virtues of a Protestant work ethic, and in form resulted in the common-school system we recognize today.

The future of American democracy required “comprehensive organization and … united effort, acting for a common end and under the focal light of a common intelligence.” Mann viewed local governments as “bunglers” who couldn’t move education to its goal of national progress. Parents also often made a hash out of their children’s education, putting society’s needs at the mercy of parental incompetence. Parents would have children for only a short period of time, but society had to deal with them for the long haul. Better, Mann believed, that society intervene early in the process rather than pay a steep price later. After all, “rulers have forgotten that, though a giant’s arm cannot bend a tree of a century’s growth, yet the finger of an infant could have given direction to its germ.”

Nearly 40 years after Mann’s death, John Dewey, in his “My Pedagogical Creed,” expressed his belief that “the teacher always is the prophet of the true God and the usherer in of the true kingdom of God.” Dewey averred that the central purpose of education was to adjust individual interest to “the social consciousness” whose theme was human progress. Granted, there are significant differences between Mann and Dewey, but the latter is clearly in the lineage of the former. Mann observed that the Lord’s prayer wouldn’t say “thy Kingdom come … on earth as it is in heaven” unless it contained the promise that it could be established here on earth, and compulsory, universal education was the key to the kingdom.

But Mann was writing in a different age. Living in what Walter McDougall called “the throes of democracy,” Mann was more keenly attuned to democracy’s excesses than was Dewey. Mann both captured and attempted to correct the excesses and the tumults of the age in his all-too-purple prose. The key to “taming the democratic beast” (Tocqueville) involved promoting the Union and emphasizing a system of education that, rather than indulging the interests of parents or sects, produced citizens not given over to the temptations of rampant individualism. A world that “quicken[s] the activity and enlarge[s] the sphere of the appetites and passions,” Mann insisted, must also “establish the authority and extend the jurisdiction of reason and conscience. In a word, we must not add to the impulsive, without also adding to the regulating forces.”

Mann’s view of human nature maintained its Calvinist pessimism. Our propensity toward selfishness overwhelms our sense of right. The “latent possibilities of evil” overwhelm us when left to their own devices. “The greatest ocean of vice and crime overleaps every embankment, pours down upon our heads, saps the foundations under our feet, and sweeps away the securities of social order, of property, liberty, and life.” Like Tocqueville, Mann saw American individualism as devolving into egoistic self-interest that had “no affinity with reason and conscience,” and the stakes of the divorce between passion and reason would be more than the “Protestant and Republican country” could bear.

Mann had traded his Calvinism for a largely secular faith in progress, accomplished by an ordered liberty, economic stimuli, and moral reform. On the policy end, “moral reform” meant the triumph of the temperance movement, of which Mann was an active advocate, and a Prussian-style system of education that would tame the savage animalism of human nature, which alone could “turn a wilderness into cultivated fields, forests into ships, or quarries and clay-pits into villages and cities.” All prior efforts to solve the problem of human sin and error had failed because they neglected “a solution so obvious” that it is as if it were “written in starry letters on an azure sky: Train up the child in the way he should go, and when he is old he will not depart from it.”

John Pinheiro in his Missionaries of Republicanism drew our attention to the ways in which anti-Catholicism drove the politics of 19th century American politics, particularly after the early waves of Catholic immigration. Mann’s suspicion—nay, hatred—of sectarian schools in general and Catholic schools in particular drove his development of the common-school system. Mann argued vigorously for a system that was compulsory, universal, and managed by a centralized bureaucracy under legislative direction. But the real key was that public education had to be nonsectarian, by which he meant above all “non-Catholic.” Though not a thoroughgoing religious skeptic, Mann became “latitudinarian” in his political thinking, meaning that he was willing to build social life on a broad foundation of religious belief without establishing any one particular church.

His 1848 “Report of the Massachusetts School Board” demonstrated his ability to walk the line between religious establishment and established religion. Responding to criticisms that the state schools were thoroughly secularized, Mann reminded the board that the “consummation of blessedness” toward which public education aimed “can never be attained without religion.”

Devoid of religious principles and religious affections, the race can never fall so low but that it may sink still lower; animated and sanctified by them, it can never rise so high but that it may ascend still higher.

With the influence of religion, men become “the most deformed and monstrous of all possible existences.” But what kind of religion, and how will it be defined and administered? Like Locke in England and some American writers, Mann advocated for a minimalist theology built “upon the most broad and general grounds.” This theology was generally Christian, but one can’t mistake its Protestant overtones. Opposing “doctrinaire” castings of the faith, Mann’s publictheology emphasized the authority of the Christian scripture, Christ as a moral exemplar, and a Providential and Supreme Being who governs human affairs both through intervention and through the creation of a “divine law” that compels moral assent. Mann insisted that their system of education “earnestly inculcates all Christian morals” as revealed in “the religion of the Bible.”

Mann distinguished between two approaches to the question of how “to secure the prevalence and permanence of religion among the people”: one approach advocates for a government-sponsored established church, while the other holds that “religious belief is a matter of individual and parental concern” that government “exercises no authority to prescribe, or coercion to enforce” to the contrary. He clearly identified the former with the oppressive governments of Europe and the latter consistent with the liberty enshrined in the “solitary example” of America. The former results from the fallacious belief “that the faith of their authors was certainly and infallibly the true faith” while the latter emerges from a skepticism of the self and respect for the elusive nature of truth, which had to “struggle for centuries” and “bleed at every pore” and be “wounded in every vital part” before it could “triumph at last,” but not until its martyrs had been sacrificed before “the throne of the civil Power” that fortified its beliefs “by prescription.” What is true for us individually ought to be held vigorously as the standard for our life but can never become the standard for our neighbor.

Mann’s religious grounding of public education could best be understood as a nativist response to midcentury Catholic immigration.

So how did Mann square this disestablishment of any particular religion with his unabashed endorsement of a more general one? He claimed that morality could achieve no proper grounding without religious belief, thus public order itself was dependent on a general religion, while specific beliefs and practices were purely private. Taxpayer dollars could not be used to advance a particular sect, but they could be used “as a preventive means against dishonesty, against fraud, and against violence.” In short, the schools had to provide the kind of biblical instruction that, in the words of the Massachusetts law establishing the common schools, would impress upon the youth

the principles of piety, justice, and a sacred regard to truth, love of their country, humanity and universal benevolence, sobriety, industry, and frugality, chastity, moderation, and temperance, and those other virtues which are the ornament of human society, and the basis upon which a republican constitution is founded.

When Is a Religion Not a Religion?

Rigidly moralistic, Mann’s religious grounding of public education could best be understood as a nativist response to midcentury Catholic immigration and the formation of parish schools. The law was dispositive because it was the state legislatures “who speak for the common heart in self-constituted assemblies” producing laws whose “reformatory power” provide “wise training for the young.” This faith in democratic processes resides alongside but overwhelms his support of religious freedom.

If men decline to coöperate with us, because uninspired by our living faith, then the arguments, the labors, and the results, which will create this faith, are a preliminary step in our noble work [emphasis added].

It is difficult for us to get our minds around the implications of this teaching because our understanding of the Establishment Clause is shaped by court cases from Everson forward that emphasize the “high wall of separation” between church and state, and such cases at their inception involved conflicts between Catholic and public schools. In one of those moments of historical irony, the outcome was to make the public schools less Protestant and less religious, thus more secular, in order to protect those schools against the charge that they were in effect religious establishments.

Just as true religion does not allow you to judge others for not agreeing with you, so too should religious education enable a child to learn to judge for himself what religion is true. Even as one wouldn’t teach the dictates of a particular political party to schoolchildren in hopes that they would vote for that party later in life but must teach politics broadly so that the child can choose a party for himself, so too one teaches religion in hopes that the child will learn how to choose religion. To support via tax dollars a school that one believes is teaching false doctrine, a citizen is “excluded from the school by the Divine Law” while at the same time “compelled to support it by human law,” and “this is a double wrong.” It is politically wrong because, forced to support the public schools financially but required by conscience to send his children to another school, the citizen must “thus pay two taxes.” It is also religiously wrong because “Divine power” itself forbids the use of coercion to advance its purposes.

Mann thus balanced the American emphasis on religious freedom and freedom of conscience against the necessity of producing the sorts of virtuous citizens whose development required a religious foundation. Even while declaiming any kind of religious compulsion, Mann also noted that any school system “cannot be an irreligious, an anti-Christian, or an un-Christian one.” But the disestablishment of any particular faith soon became, in the hands of others, a disestablishment of all faith and, the principle having been conceded, the grounds for contestation were removed.

Such zealous regard for disestablishment became for the believers in progress their own gravedigger.

Such zealous regard for disestablishment became for the believers in progress their own gravedigger, repeating the error of Mann’s optimism that broad religious establishment could withstand the acids produced by nonsectarian disestablishment. Mann took it as obvious that it would be absurd for schools to support a particular party or program or substitute some alternative religion for the Christian one. This is, arguably, exactly what has happened in our schools, and we find ourselves in the middle of a new kind of disestablishment whose legal battles and consequences and heated exchanges mirror those of the past. And it’s no surprise that the adherents of the new faith share Mann’s confident assumption that social life is impossible without its creeds and shaping of moral character. Neither is it a surprise that those who have an alternative faith want to opt out and not bear the burden of the “double tax” Mann so forcefully condemned. And just as the last battle of Protestant disestablishment took over 100 years to settle, it is likely that our current battle faces a similar time frame, if we have but the patience to work it out.