It is a common habit of progressives to denounce various aspects of American history as racist, sexist, or in some other way bigoted. The U.S. Constitution, we are often reminded, had a “three-fifths clause” that counted blacks as less than whites—for purposes of congressional representation. The clause, rightly, is denounced as a stain on our founding charter. The missing context, however, is that it was the abolitionists who did not want blacks to be counted at all, while the slaveholders wanted them to be counted in full, so as to give the slaveholding South more political representation and power. The progressive historian Charles Beard launched a new front, arguing that the Constitution was drafted to protect the wealth and property of the people who wrote it. It wasn’t until the 1950s that Forrest McDonald and others debunked Beard’s shoddy and polemical history. Another oft-heard gripe is that the franchise wasn’t granted to everyone overnight. Women couldn’t vote for a century or more, and non–property holding men had to wait a while as well, though not as long.

Another attempt by a New Right thinker to lay out all that went wrong with the American experiment proves to be little more than daft history wedded to worse philosophy.

By Patrick Deneen

(Sentinel, 2023)

My standard response to such progressive indictments is that, yes, these things look bad when measured against the yardstick of the present. But you’re using the yardstick wrong. The correct comparison is between the Founding and what came before it. Prior to the Founding, there was no democracy and precious little in the way of inalienable rights for anyone but nobles and monarchs.

In short, the American Revolution launched a new chapter in human history, and while those drunk on the fierce arrogance of Now may condemn it for not fully implementing its ideals in every particular all at once, those alive at the time saw it for what it was. For instance, not long after the “Shot Heard ’Round the World,” the Holy Roman Emperor, Joseph II, told the British ambassador to the Austrian imperial court, “The cause in which England is engaged ... is the cause of all sovereigns who have a joint interest in the maintenance of due subordination ... in all the surrounding monarchies.” Joseph’s mother, the Dowager Empress, wrote to George III to express her “hearty desire to see the restoration of obedience and tranquility in every quarter of his dominions.”

Grant this to Patrick Deneen, the author of Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future—he doesn’t repeat the progressive mistake. Instead, he proudly holds the yardstick up to the present and finds the past better in almost every regard. I don’t just mean the 1950s or the 1850s, arguable—yet contestable!—claims. Rather, he insists that, by the time of Lexington and Concord, the horse had already left the barn: things had gone catawampus for the West a century earlier.

As with his previous book Why Liberalism Failed, Deneen looks upon the great expanse of progress since the Enlightenment and shudders. His complaint isn’t merely that the West’s embrace of liberalism meant too many sacrifices in pursuit of progress; it’s that embracing progress as a concept—both moral and material progress—was a kind of original sin.

Deneen never adequately defines progress in Regime Change, but he is constantly throwing shade on the term.

Deneen never adequately defines progress in Regime Change, but he is constantly throwing shade on the term. The left’s belief in moral progress gave us wokeness and other horribles. The right’s belief in material progress gave us everything from closed factories and climate change to anomie. As with his previous book, Deneen writes like a prosecutor, downplaying inconvenient facts and evidence in his brief—or leaving them out entirely—while pounding the table about damning circumstantial evidence and anecdotes.

Thus, looking back at some five centuries of rising life expectancy, exploding living standards, population growth, literacy, etc., Deneen could declare in Why Liberalism Failed: “Among the greatest challenges facing humanity is the ability to survive progress.”

In this sequel of sorts, many of the familiar characters are once again in the dock, starting of course with John Locke. His Second Treatise on Government (1690) inflicted upon the world a new metaphysic of self-interest that in turn led to the corrosion of custom, tradition, and the classical political tradition Deneen prefers. Locke’s “radical new definition of property that extended not only to material objects, but to ownership of self [italics his],” inexorably unleashed the execrable notion that rewarding merit should be considered a social good. “The liberal regime came into being not mainly to protect property rights—though that was an important political imperative—but to legitimate the ruling principle that would encourage the formation and ascendancy of the ‘industrious and rational.’” This “progressive” innovation led to the invidious concept of merit and the “despotic” and “tyrannical” rule of today’s “meritocracy.”

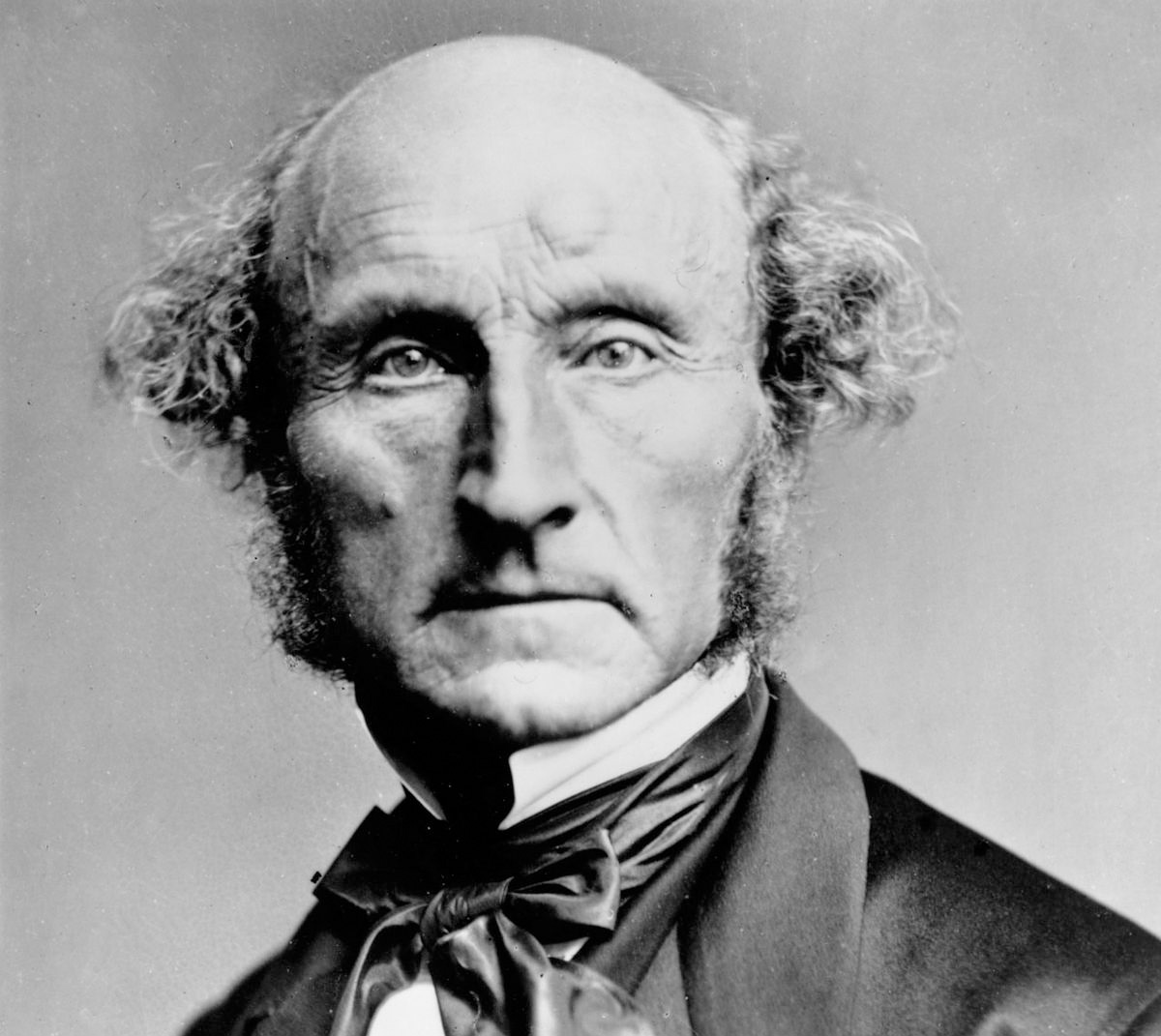

John Stuart Mill made everything worse by declaring war on the authority of “custom,” which let loose a kind of virus of the mind. Mill’s call for “experiments in living” added an acidic libertinism, eroding the institutions necessary to a healthy order, and informs, at a metaphysical level, the morally bankrupt ideology of both the progressive-left and the classically liberal right.

Even poor Adam Smith is charged as a co-conspirator. His crime lay not so much in pointing out that the division of labor was essential for economic progress, but for saying that prosperity was worth pursuing at all. Smith acknowledged that the division of labor could “stunt the reflective capacities” of some workers who would increasingly specialize on specific stages of the means of production. But, Smith argued, the concomitant prosperity generated from such efficiency made it an acceptable trade-off. (Life expectancy in the U.K. when Smith was writing was about 39 years, and about a third to half of children didn’t survive childhood.) But for Deneen, growing material prosperity for all wasn’t worth it. Men, you see, lived much richer lives when they made more expensive pins from scratch by themselves in the isolation of their dimly lit workshops. (I do wonder why Deneen simultaneously laments the opening of factories in the 18th century and the closing of them in the 21st.)

“The many” are far less homogeneous than Deneen’s manifesto rhetoric would suggest.

What unites these and other liberal villains was their emphasis on the benefits of separation—separation of powers, separation of public and private, religious and secular, individual and social, the “few” and “the many.” Deneen writes that the “successor regime” to our current one “must eschew liberalism’s core value of separation, and instead, seek a deeper and more fundamental and pervasive form of integration.”

How do we get to this post-liberal integral order? The author looks to the premodern political theory of Aristotle, Aquinas, and the Greek historian and theorist Polybius as the architects of his new—sorry, old—“common good conservativism.”

Now, I should say that there’s much to his version of conservatism that I have no problem endorsing, in part because so much of it is hardly new to traditional American conservatism. But you wouldn’t know that from reading Deneen’s version of conservative intellectual history, particularly in the first third of the book, in which he stridently lays out his argument that conservatives prior to his “New Right” kin were nothing more than fellow-traveling libertarians or “right-liberals” uninterested in, or ineffectually cowardly in defense of, traditionalism of any kind. Indeed, his whole schema depends on asserting that the “ruling class” is essentially an undifferentiated blob of left-liberals and right-liberals who share power for their own benefit against the interests of the many.

This regime is at best a duopoly of libertarians or classical liberals and progressive liberals, and at worst a Potemkin facade for a monolithic “elite” exemplified by “Woke Capitalism,” which Deneen describes as the “perfect wedding of the ‘progressivist’ economic right and social left.” Similar Twitter-ready claims clutter the early pages and should tip off readers not looking for talking points they already agree with. Not only is there little to no evidence to support the idea that mainstream conservatives favor Woke Capitalism, but there’s no reason to believe that mainstream libertarians support it either. Heck Milton Friedman—scourge of corporate “social responsibility”—would have torched the idea.

In these early pages, “populism” is almost always in scare quotes, a term used by “elites” and “the ruling class” to demonize “the many” who are economically statist and socially conservative. But when Deneen uses populist without scare quotes, it’s always a positive term to describe the virtuous masses who “are achieving ‘class consciousness’—not as Marxists, but as left-economic and social-conservative populists.” With his admiring references to the likes of Tucker Carlson and Kurt Schlicter, and his ad hominem uses of “Never Trump” to discredit arguments he refuses to contend with (including my own), it’s almost as if he hopes that the Very Online right that eats this stuff up won’t read much beyond the introduction or index—or title.

It’s not until much later that Deneen admits the obvious: “the many” are far less homogeneous than his manifesto rhetoric would suggest. We have to wade through many chapters to discover that Deneen acknowledges that elites are inevitable and not inherently illegitimate. Indeed, they are a requirement for his “Aristopopulism” to work. After insinuating that “Never Trump” is code for “elitist” or “liberal” for half the book, he finally concedes on page 152 that Trump is a “deeply flawed narcissist.”

The truth is that the whole point of the book is much more modest—and underwhelming—than the title and revolutionary-cosplay chapter titles suggest. Whereas, according to political theory, “regime change” means the wholesale replacement of a system of government, usually by force, Deneen’s Regime Change boils down to the idea that we need to replace the existing elites, specifically on the right, with a “New Right” of people who think like Patrick Deneen. Still, there is a tiny threat to the actual regime in his mission statement: “What is needed, in short, is regime change—the peaceful but vigorous overthrow of a corrupt and corrupting liberal ruling class and the creation of a postliberal order in which existing political forms can remain in place, as long as a fundamentally different ethos informs those institutions and the personnel who populate key offices and positions” [italics mine]. In other words, so long as my team is in charge, we can keep the Constitution and all that stuff. I’d find this more worrying if I thought this tiny cadre of reactionary malcontents could get a post-liberal integralist elected dogcatcher.

Regardless, given that today’s New Right is, by my rough count, at least the fifth self-declared New Right since World War II, I find such highfalutin tough talk less worrisome—and less impressive—than the integralists might think. This is a very old story about a very old strategy. A cranky faction of the right decides it has that special gnosis and that they are the only legitimate standard bearers for their side. They denounce the (alleged) holders of power and influence as fakers, RINOs, closet progressives, Me-too Republicans, sell-outs, squishes, wets, and so on in order to claim that history must make room for the new priests of the True Faith. Often, the mainstream media will hype the New Right insurgents to use it as a cudgel against the establishment right they already despise. Not knowing that this attention is purely instrumental and short-lived, these rebels become all the more convinced they have History on their side.

The intellectual history of the right—and left—is replete with such efforts. The orthodoxies and heresies change (somewhat) almost every decade, as do the terms for them. People are declaring Libertarian Moments and Neoconservative Moments and Nationalist Moments all the time. It’s moments all the way down.

Stripped of its disquisitions on Aristotle and Aquinas and oddly envious or trollish allusions to various leftist radicals (one chapter borrows its title from Lenin’s What Is to Be Done? and another from C. Wright Mills’ The Power Elite), Regime Change looks more like just another moment where one faction leaps at an opportunity to get to the top of the greasy pole.

So while I can’t begrudge Deneen and his fellow neo-integralists an old-fashioned effort to muscle their way to the commanding heights of the right—which, in fact, commands very little—I must object to much of the analysis he employs to justify his putsch.

Admittedly, part of my objection is parochial. His endlessly repeated claim that conventional modern conservatives over the past half century have been willing aiders and abettors of progressivism amounts to little more than what the cool kids call “retconning”—rewriting the accepted storylines to get right with younger fans. The idea that the likes of free market conservatives such as Michael Novak, author of The Catholic Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, William F. Buckley, Irving Kristol, and Thomas Sowell were willful, or unwitting, accomplices of progressivism is as unserious as Tucker Carlson’s claim that the right side of the aisle in the Capitol is comprised of “libertarian zealot[s] controlled by the banks.”

Much of Deneen’s indictment is simply a restating—with attribution—of James Burnham’s brilliant work The Managerial Revolution. That’s fine (I do likewise in Suicide of the West). But Burnham was a co-founder, columnist, and intellectual lodestar for National Review. There’s some nuance and gratitude missing when you borrow so much from a foundational thinker of modern conservatism while simultaneously denouncing modern conservatism. More amusingly, many of the contemporary conservatives Deneen heavily relies on for his descriptions of America—including my AEI colleagues Tim Carney and Charles Murray—are profoundly libertarian on economics (see Murray’s What It Means to Be a Libertarian and Tim Carney’s The Big Ripoff). Apparently, they’re fools except when they make arguments and observations ripe for neo-integralist cherry-picking.

The biggest problem with the arguments of anti-liberals—most of whom are far less erudite and subtle than Deneen himself—is an almost contemptuous disregard for history and culture despite claims of mastery over both. For example, Deneen laments how university faculty have retreated to specialized intellectual “silos” where the only “shared commonality, according to one legendary half-jest, is a universal complaint about campus parking.” I can’t help but think Deneen would have benefitted from walking down the hall and picking the brains of some historians and political scientists.

Much of Deneen’s analysis seems to float high in the Platonic aether or low upon the surface of the Twitter sewer.

Instead, Deneen stays in his comfort zone, offering an extended appeal to the authority of classical thinkers. The result is that much of his analysis seems to float high in the Platonic aether or low upon the surface of the Twitter sewer, disconnected from both the societies his philosophical heroes lived in as well as the country he looks out upon in 2023. For starters, it’s fine as a matter of bombast or poetic license to compare the sins of the existing “ruling class” with the virtues of the pre-Enlightenment ruling classes. But it would be nice if there were a bit more acknowledgement that the pre-modern ruling classes actually ruled, sometimes over slaves and serfs. Their authority derived from fictions about noble blood and Divine Right. Today’s so-called ruling class aren’t equivalent rulers, not least because those controlling the government must subject themselves to the approval of “the many” through these things called “elections.” And all of them are subject to the rule of law, one of those glorious triumphs made possible by the liberalism he despises. Aristocrats—and philosophers!—of virtuous antiquity could live in the open like Jeffrey Epstein exploiting young girls—and boys!—without apology. The bright light of day in our decadent regime drives such miscreants to suicide. Similarly, you can tell Deneen is ensorcelled by these metaphorical comparisons when he claims that “essential workers” during the pandemic “resemble a class of serfs” ruled by a rootless “liberal aristocracy.”

Most Americans know nothing of Locke and Mill and perhaps only slightly more of Adam Smith. They know dismayingly little—if polls are any guide—about the finer points of the Founding or the fine print of the Constitution. But that doesn’t change the fact that Americans are exceedingly liberal in their attitudes and expectations. According to a 2021 survey by Gallup, 84% have a positive view of free enterprise. A 2019 survey found that majorities prefer the free market to take the lead on “technological innovation” (75%), the “distribution of wealth” (68%), and the “economy” and “wages” (62% each). Polls routinely find that Americans place a very high value on the liberal lynchpins of the existing “regime”—from free speech and fair trials to property rights and religious freedom. “Merit” also polls quite well.

Polls change, of course. When “capitalism” is in bad odor, “socialism” becomes more popular and vice versa. Partisanship often drives public opinion in favor—or disfavor—of all manner of public policies. But the simple fact is that American culture is an extension and amplification of the decidedly liberal culture we inherited from England. As De Tocqueville said, “The American is the Englishman left alone.” The revolutionary generation believed they were seeking to secure “their ancient English rights and liberties.” As Harvey Mansfield has observed, nearly all American political conflicts boil down to arguments over competing rights. Americans love their rights, because Americans are irretrievably liberal. I love the image of populism-enthralled integralist eggheads explaining to members of Bikers for Trump that they need to sign up for a confessional state that bans pornography. Deneen derides “fusionism” as the elitist “top down conservatism” that he seeks to dethrone (as if it still sat on a throne). This is a profoundly elitist, almost cartoonish understanding of how elites operate and what fusionism was. Frank Meyer, the primary author of fusionism, argued that the tensions between liberty and order, freedom and virtue, the individual and the collective, were deeply embedded in the DNA of Western civilization in general and the Anglo-American tradition in particular. And he was right.

The idea that you can easily translate the ideas of Aristotle, Aquinas, and Polybius into an alternative 21st century regime that erases or supplants the deeply embedded cultural preferences of Americans is otherworldly. The best an Americanpolitical movement can hope to do is tease out aspects of their thought that complement the American character. Ironically that is precisely what the Founders thought they were doing. Deneen presents Polybius’ idea of a “mixed regime” or “mixed constitution” as a clearcut alternative not just to what we have now but also to the regime set up by the Founders. But many Founders were well-versed in Polybius—and the Polybius-indebted Montesquieu—and saw their system of checks and balances and divided government as a fulfillment of such ideas. (Ironically, while the Founders were deeply indebted to Locke’s empiricism, they were not particularly influenced by Locke’s Second Treatise.)

America has some deep and worrisome problems. As Adam Smith said, “There’s a great deal of ruin in a nation.” Deneen’s descriptions of some of them are fairly unobjectionable, but his prescriptions will likely join the musings of previous frustrated conservatives and reactionaries unwilling to accept that Americans just aren’t that into them. Because they’re Americans.