In the New Testament, Paul introduces himself to his readers as an “envoy” and an “ambassador” of Christ Jesus. While we might be quick to glance over such designations or translate them into the familiar Christian theological sobriquet “apostle,” such titles carried with them a certain amount of political and cultural significance in the first century. Throughout Asia Minor, various inscriptions bore homages to Augustus Caesar as the world’s “savior,” and emissaries throughout the Roman Empire spoke of the “good news” of his reign. Of course, Paul spoke on behalf of a very different kind of ruler, the crucified and resurrected Jesus, who had commissioned him to preach “obedience of faith among all the nations” (Rom. 1:5). Given the imperial Greco-Roman context that the first Christians moved in, what should we make of these rhetorical similarities between the gospel preached by Paul and the gospel promoted by Caesar? Was Paul being strategically subversive, perhaps even revolutionary? How oblique or explicit was Paul in using these imperial Roman motifs and terminology? Just how political was the Apostle Paul? The Apostle and the Empire: Paul’s Implicit and Explicit Criticism of Rome by Christoph Heilig attempts some answers.

How political was the Apostle Paul? Did he directly challenge the Roman regime by declaring Jesus as Lord and bringer of the true “Good News”? Or is the attempt to paint him a perennial advocate of regime change a reflection of modern obsessions?

By Christoph Heilig

(Eerdmans, 2022)

Since the 1970s, following the lead of scholars such as Neil Elliott, Dieter Georgi, and Richard A. Horsley, such questions have ignited a whole industry of studies on the relationship of Paul and the Jesus movement to the Roman Empire. The Society of Biblical Literature annually hosts a whole unit devoted to “Paul and Politics,” and academic publishers have produced a wealth of titles related to the subject. But such scholarship has not been limited to the halls of the academy; it has also become popular among clergy and laity, and from diverse confessional and theological perspectives. For example, popular biblical scholars N.T. Wright and John Dominic Crossan, despite their numerous theological differences, both claim that Paul’s gospel directly commented on and criticized the Roman Empire.

Much like how Candida Moss and others have challenged the idea of widespread and intense early Christian persecution and martyrdom, Heilig suggests that the Pauline churches may not have faced the “concrete sanctions or looming threats” suggested by other New Testament scholars. This is not to say Paul and his later Christian comrades did not face any legal problems, as the letters between Pliny and Trajan on what to do with Christians attest. Building off the work of Laura Robinson, part of the problem according to Heilig is how these scholars misunderstand the Roman Empire as some kind of “police state.” But even if Rome was not a totalitarian state, this does not mean Paul and the first Christians were ideal Roman subjects. One need only read the Acts of the Apostles or Paul’s own references to his brush with Roman authorities to see that he was a “highly visible troublemaker.” But it is precisely because of the wide reaches but hard limits of Roman religious tolerance that Heilig implores readers to think in more nuanced ways when it comes to supposed “hidden criticism” of the Roman Empire in Paul’s letters.

One need only read Paul’s own references to his brush with Roman authorities to see that he was a “highly visible troublemaker.”

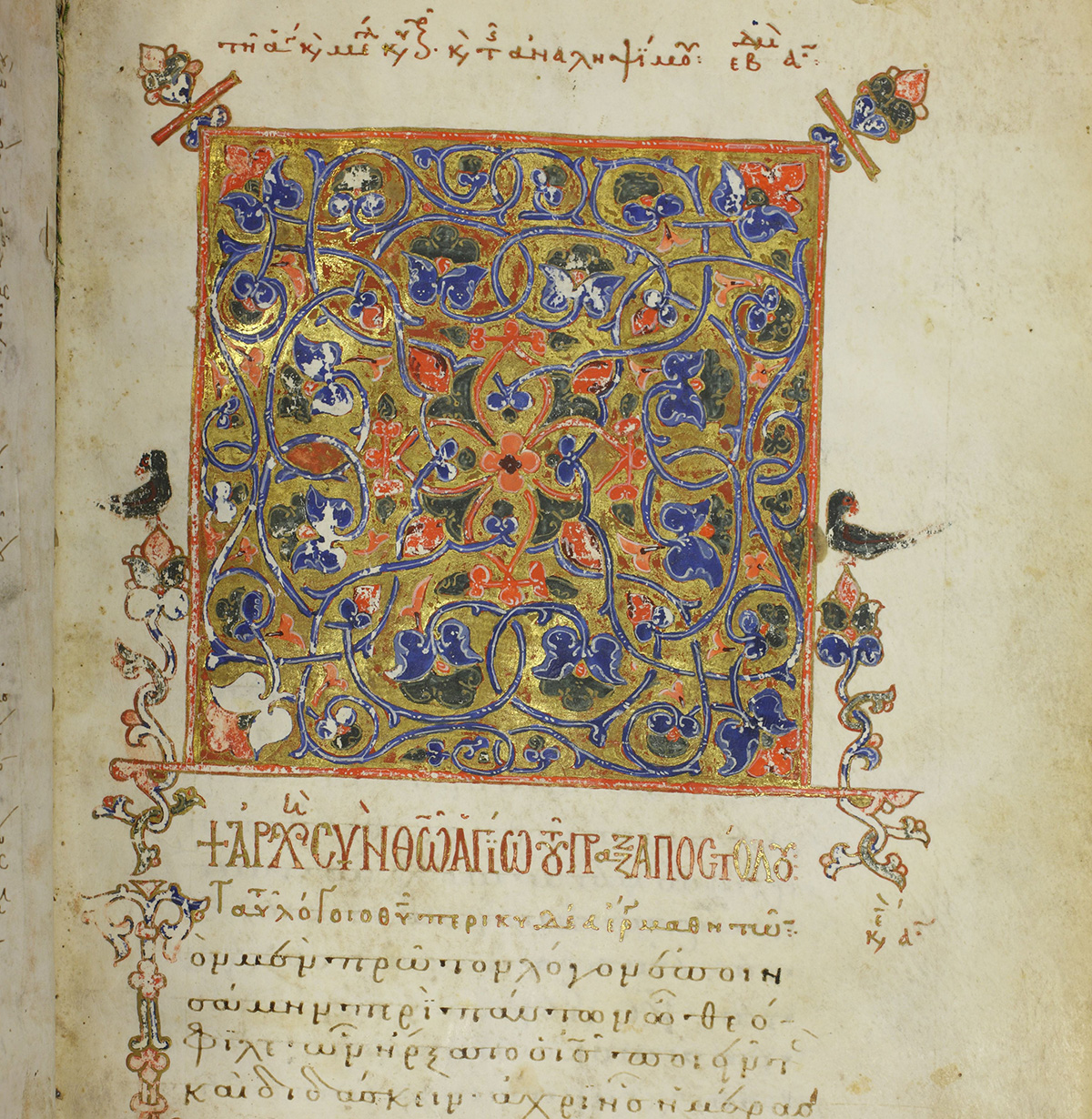

Putting his criticism and approach into practice, Heilig spends the bulk of The Apostle and the Empire focusing on 2 Corinthians 2:14: “But thanks be to God, who in Christ always leads us in triumphal procession and through us spreads in every place the fragrance that comes from knowing him.” With an extensive amount of literary material (such as letters, poems, inscriptions) and archeological evidence, Heilig argues that this is possibly an allusion to Claudius’ triumphant procession in Rome celebrating his victory over Britannia in 44 A.D. Taking for granted that Paul was an “active observer of his contemporary context,” Heilig points out several inscriptions found at Corinth hailing Claudius’ victory, as well as the evidence of the yearly cultic celebrations taking place in Corinth, during which the emperor was personified by a pagan priest during these rituals and celebrated for his conquest. During his stay in Corinth, Paul would have seen and experienced these displays of Roman imperialism, making the allusion in 2 Corinthians 2:14 even more salable. Perhaps more tantalizing is Heilig’s linkage of the celebration of Claudius’ victory to Paul’s co-workers in Corinth, Priscilla and Aquilla. According to Acts 18:1–3, Priscilla and Aquilla had been working in Rome as tentmakers before being expelled in 50 A.D., making them potential eyewitnesses to Claudius’ procession. Given these events and connections, it’s “hard to imagine that Claudius did not feature in these discussions” between Paul, Priscilla, and Aquilla. While still speculative, Heilig’s presentation is as conceivable as it is exciting.

With this context in mind, Heilig highlights what he views as the most provocative elements of Paul’s allusions. By fusing Jewish eschatological expectations with Roman military imagery, Paul’s “metaphorical replacement of the emperor with the Jewish god YHWH” was clearly an act of subversion. Paul’s Corinthian readers, therefore, would draw comfort from such allusions given their new outsider status as Christians. Paul creatively reminds readers, alienated as they were from large parts of Roman society, that God is greater than the emperor. But before modern readers get overly excited by Heilig’s conclusions, he argues that passages speak more to Paul’s “unease” with the empire as opposed to complete apathy or severe criticism on either end of the spectrum. Subversive is not the same as confrontational, after all: completely absent from Paul is the call to open armed rebellion. As Heilig puts it, Paul “seems to challenge basic assumptions of Roman ideology,” which most likely reflects Paul’s “sense of unease in relation to Roman demonstrations of military powers.” In short, Paul may not have been directly attacking Caesar, but he was certainly using contemporary events and his political reality to his rhetorical advantage and situational needs.

Rather than looking for “hidden” clues or anti-imperial Roman “codes,” Heilig implores future scholarship and exegetes to focus on specific historical circumstances. To help in these future endeavors, Heilig champions incorporating modern archeological evidence as well as ancient lexical data being produced by new digital humanities ventures. In Heilig’s view, Romans 13, the most politically fraught section of the Pauline corpus, is in dire need of such a treatment. The result might be a more complex vision of the politics of the ancient church. The first Christians were neither rebels with a cause nor model citizens. Paul was not naive to his Roman reality, but he was clearly uncomfortable with many elements of it, such as the consumption of food offered to idols and some of Rome’s sexual ethics.

One of the remarkable things about Heilig’s work is how many audiences he is writing for. On the one hand, he is addressing a lively debate within the field of Christian origins and New Testament studies while clearly having an eye out for Christians (both clergy and laity) who are excited by or unnerved by the modern political usefulness of Paul’s writings. With these dual and sometimes overlapping audiences in mind, at one moment Heilig is addressing the thorny political situation of first-century Corinth, then a few pages later discussing the violent Christian nationalism displayed at the January 6 insurrection or the references to Paul’s letters by Jeff Sessions. Because much of Heilig’s criticism is not exactly new but rather a popularizing of his 2015 work Hidden Criticism? The Methodology and Plausibility of the Search for a Counter-Imperial Subtext in Paul, this twin approach makes sense as it will offer engaged lay readers examples to draw from.

Despite being such a slim volume, The Apostle and Empire can be dense reading at times, speaking more to those well versed in this corner of Pauline studies than, say, your average politically interested pastor. But given N.T. Wright’s overwhelming popularity with large sections of evangelical American Christians, Heilig’s insights are well argued and should be considered by those too eager to turn Paul into an ancient Malcolm X. Going beyond the false binary of apolitical and political, Heilig’s work is encouraging because of its emphasis on the lived reality of those under imperial threat, as well as the small but meaningful ways power can be challenged. Paul may not have been a revolutionary, but by claiming that Jesus was Lord (and indicating that Caesar was not), he was still a radical.