In his foreword to Cory C. Brock and N. Gray Sutanto’s Neo-Calvinism: A Theological Introduction, George Harinck notes:

Internationally the interest in neo-Calvinist dogmatics is on the rise. A new generation of theologians from all over the world, and often without historical connections with the Dutch neo-Calvinist tradition, came into contact with its theology through the translations of Bavinck’s Reformed Dogmatics, Kuyper’s Stone Lectures on Calvinism, and many other publications they wrote. Since about 2000 this translation got a new and decisive impulse and developed into an industry, thanks to many, but especially through the effort of John Bolt (Bavinck) and Rimmer De Vries (Kuyper).

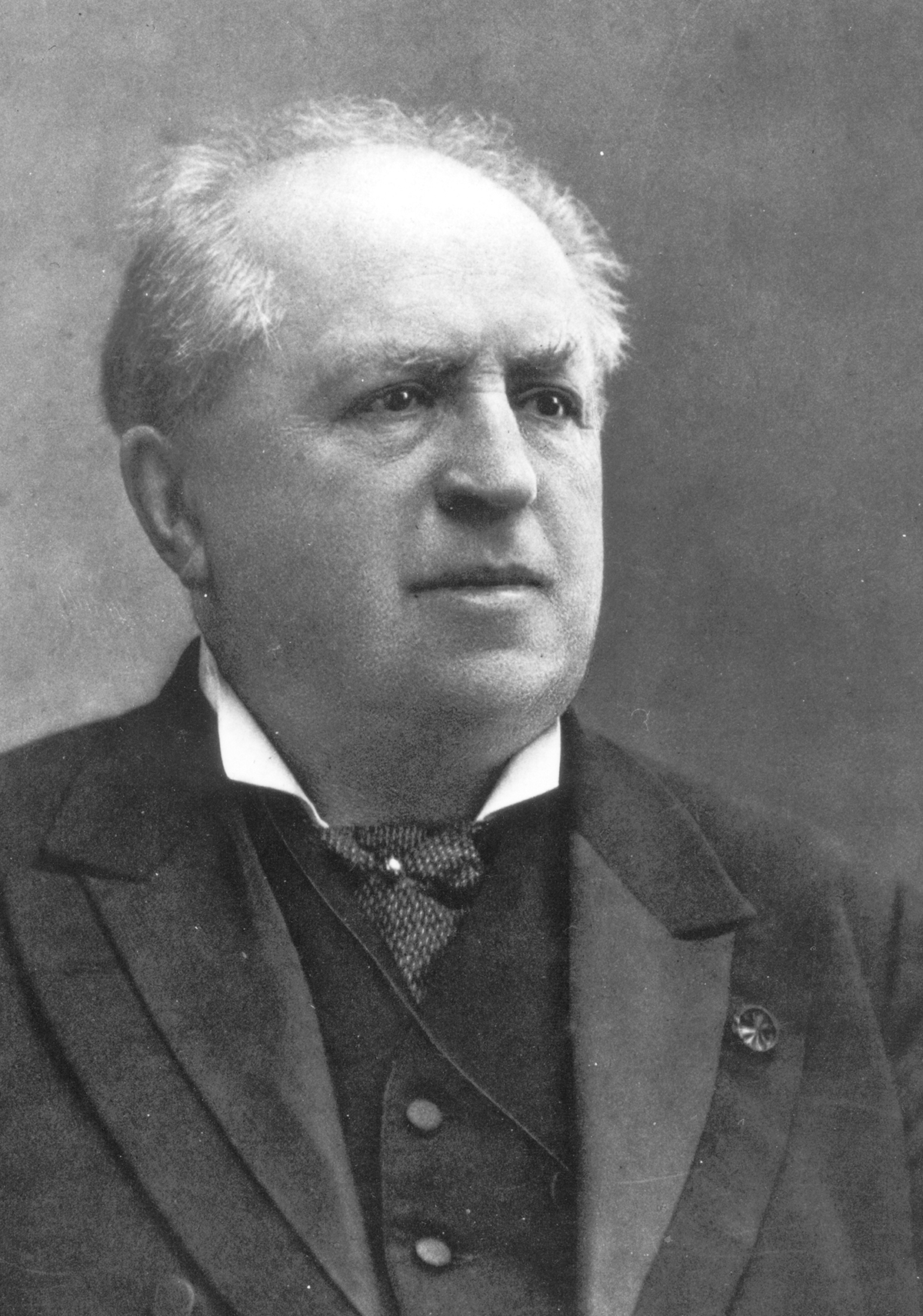

A new introduction to the neo-Calvinist thought of Abraham Kuyper and Herman Bavinck attempts to fill a void in the scholarship on this important theological movement. But does its slighting of one theologian in favor of another ultimately undermine its intentions?

By Cory C. Brock and N. Gray Sutanto

(Lexham Academic, 2022)

Indeed, the Acton Institute has had the privilege, in partnership with Lexham Press, to publish a 12-volume Collected Works of Public Theology by Kuyper, the result of a decade of efforts from the Abraham Kuyper Translation Society and the generosity of De Vries, among others.

In my own academic work on Kuyper, I would appear to exemplify Harinck’s point about the rising international and ecumenical interest in neo-Calvinism. I am a Scots, German, and Irish American, and a Greek Orthodox one at that. But I’m also an alumnus of Kuyper College and Calvin Theological Seminary. My familiarity with and interest in Reformed theology and neo-Calvinism, Kuyper in particular, has been ongoing for more than a decade.

Alas, many popular and even some scholarly works on neo-Calvinism offer a theologically superficial picture of the tradition. Brock and Sutanto acknowledge this problem and aim to correct it: “Though the studies that explore the implications of neo-Calvinism on public theology, politics, and philosophy are exciting, worth investigating in their own right, and intertwined with the work of dogmatics, this imbalance is unfortunate.” Thus, they state the book’s aim at the end of their introduction: “By sketching the dogmatic roots and contours of neo-Calvinism, we hope to reground the neo-Calvinist tradition in its own catholic roots and also to invite nonspecialists from other backgrounds to draw on this tradition for their own work.” A book like this has been needed for a long time now, but have Brock and Sutanto finally filled this long-vacant niche in the neo-Calvinist ecosystem?

I’m of two minds.

Any book that clearly defines its terms gets at least one cheer from me. Brock and Sutanto limit their sources and time period: “We define neo-Calvinism as a specific, historical movement of neo-confessional Calvinism in the Netherlands of the long nineteenth century.” As they are particularly interested in the roots of neo-Calvinism, they further limit this to the works of Abraham Kuyper and Herman Bavinck as the two earliest theological minds of the movement: “The term ‘neo-Calvinism,’ then, refers to their development of [John] Calvin’s theology into a holistic worldview that had a particularly God-centered orientation toward all things within the context of the modern consciousness.” At points they even note influences reaching beyond Calvin to several other early Reformed theologians—such as Franciscus Junius, Jerome Zanchi, and Francis Turretin—as well as back further, to Thomas Aquinas, Augustine of Hippo, Cyril of Jerusalem, and Athanasius of Alexandria. Yet, in emphasizing the modern and contemporary adaptation of neo-Calvinism, they also correctly note the influence of German philosophical sources, such as Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Schleiermacher, and Arthur Schopenhauer. As they put it in the first of the 16 theses with which they conclude the book, “Neo-Calvinism is a critical reception of Reformed orthodoxy, contextualized to address the questions of modernity.”

These theses are another bright spot of Neo-Calvinism. They might serve as a handy checklist for readers. How do you know you’ve absorbed the insights of this book? For example, do you know what Brock and Sutanto mean when they claim in thesis 5, “‘Organicism’ and ‘organic unity’ are fitting terms to describe creation’s many unities-in-diversities, as it analogically reflects the Triune God”? You will if you read chapters 5 and 7. (Spoiler: As the Holy Trinity is one unity with three distinct-but-inseparable members, so also creation reflects this divine reality, constituting an organic whole that nevertheless contains many distinct members.) You can read through these theses and mentally check off each one you now understand after having read what preceded them. I love it. I only wish they were presented in the introduction rather than being buried at the very end, in the conclusion, so that readers could have them in mind from the start. It would have been even better if each chapter had developed Kuyper’s and Bavinck’s arguments for a single thesis. To be sure, those arguments can be found throughout the book, but as it is, finding them could be more intuitive. That’s only a minor complaint, however, as many books fall far short of the clarity of Neo-Calvinism in that regard.

These theses are another bright spot of Neo-Calvinism. They might serve as a handy checklist for readers. How do you know you’ve absorbed the insights of this book? For example, do you know what Brock and Sutanto mean when they claim in thesis 5, “‘Organicism’ and ‘organic unity’ are fitting terms to describe creation’s many unities-in-diversities, as it analogically reflects the Triune God”? You will if you read chapters 5 and 7. (Spoiler: As the Holy Trinity is one unity with three distinct-but-inseparable members, so also creation reflects this divine reality, constituting an organic whole that nevertheless contains many distinct members.) You can read through these theses and mentally check off each one you now understand after having read what preceded them. I love it. I only wish they were presented in the introduction rather than being buried at the very end, in the conclusion, so that readers could have them in mind from the start. It would have been even better if each chapter had developed Kuyper’s and Bavinck’s arguments for a single thesis. To be sure, those arguments can be found throughout the book, but as it is, finding them could be more intuitive. That’s only a minor complaint, however, as many books fall far short of the clarity of Neo-Calvinism in that regard.

A third bright spot is that despite their emphasis on theology in itself, Brock and Sutanto continually connect the theological insights they explore to Kuyper and Bavinck’s principles for Christian social engagement, such as common grace, the antithesis, and sphere sovereignty. Once again, they succeed in offering clear definitions. Common grace “is the fact of [God’s] loving patience in preserving both humanity and the creaturely cosmos despite human rebellion and its polluting corruption for the sake of redemption.” The antithesis is “the antithetical relation between the kingdom of Christ and that of this world [that] is not ontological but ethical…. The enemy is sin, Satan, and the principle of the flesh at work in the hearts of human beings.” Moreover, “Kuyper describes this antithesis through the lens of redemptive history accordingly: “After the fall into sin and curse, a new seed”—Jesus Christ and new humanity of the Church—“had to be replanted that would grow in the fullness of time and refresh the dead body that was once a living organism.” Lastly, sphere sovereignty begins with the reality that

Christ is the King of the kingdom, and … he has determined to administer his rule through the many authorities that occupy the multiple spheres of creation. In each sphere God has granted an aspect of authority and a relative freedom from the authorities of the other spheres. Simultaneously, there are no hard borders between these spheres, but … working at their best [they] are an organism of relations.

Brock and Sutanto continually connect the theological insights they explore to Kuyper and Bavinck’s principles for Christian social engagement, such as common grace, the antithesis, and sphere sovereignty.

Not only do they do justice to the many neo-Calvinist social principles rather than selecting just a few, they helpfully do so in the context of a deeper exploration of their theological grounding.

Neo-Calvinism, despite its improvements over other, similar books on the market, retains some major defects, however. First, Brock and Sutanto do not sufficiently establish the uniqueness of their theses. Comparisons of neo-Calvinism to contemporary Roman Catholicism, or at least Kuyper’s and Bavinck’s perception of it, can be found, but the extent to which neo-Calvinism differs from—or dovetails with—other contemporary Protestant traditions cannot be discovered from reading this book.

The most important of these, to my mind, would be Lutheranism. Kuyper and Bavinck reference Lutheran theologians like Adolf Von Harless and Hans Lassen Martensen in their works. Bavinck lists both as among the foremost ethicists of the 19th century in his Reformed Ethics, in fact. While Kuyper and Bavinck have their criticisms of Lutheranism, they also constructively build upon Lutheran ideas in the development of their theology. These figures demonstrate neo-Calvinism’s “catholic” commonalities with, rather than uniqueness from, contemporary Lutheranism. For example, one can find clear antecedents in Von Harless’ 1842 System of Christian Ethics to the unfolding of what Kuyper called the “progressive” aspect of common grace throughout history, a treatment of which Neo-Calvinism lacks. A comparison with a near contemporary Lutheran like Dietrich Bonhoeffer might have been fruitful as well, given the authors’ appeal to Bavinck’s categorization of “family, church, state, and culture” as “meta-spheres,” which seem to correspond exactly to Bonhoeffer’s conception of four creational “mandates” in his Ethics.

This leads me to a second, more severe defect. While Brock and Sutanto note that Kuyper never isolates meta-spheres in the same way as Bavinck, there are many instances where no differences between the two theologians are acknowledged. On my reading, the book tends in those cases to collapse the neo-Calvinist viewpoint into Bavinck’s at the expense of Kuyper’s.

For example, consider Brock and Sutanto’s account of conscience. They claim that, based on the need for common grace, “Bavinck and Kuyper both sharply question just how common the appropriation of natural law is.” In support of this claim, however, they cite only Bavinck’s account of how “while the moral order and natural law are reality, the domains of historical context, human desire, and sin restrict the epistemic possibilities for the human conscience to receive said moral order commonly and correctly due to the complexity of the embodied self.” Thus, while acknowledging natural law, by the authors’ presentation Bavinck would seem to anticipate Alisdair MacIntyre in claiming that conscience’s witness is mediated, “operat[ing] according to a plethora of situated logics.”

Contrast this with Kuyper’s statements in Our Program. To Kuyper, “conscience is the immediate contact in a person’s soul of God’s holy presence, from moment to moment. Withdrawn into the citadel of his conscience, a person knows that God’s omnipotence stands guard for him at the gate.” Conscience is the moral basis of the sovereignty of nonstate spheres, such that “the only point of support that has ultimately proved invincible and indomitable over against the power of the state is the conscience.” Indeed, as Kuyper begins his treatment of the topic, “The conscience marks a boundary that the state may never cross.”

While Kuyper and Bavinck have their criticisms of Lutheranism, they also constructively build upon Lutheran ideas in the development of their theology.

To be fair, the authors do note that Bavinck supported freedom of conscience, and we can add that Kuyper also believed the conscience to be corruptible and in need of palingenesis (regeneration). But at the very least, there appears to be a sharp contrast of emphases, if not also of content. Does social context determine the content of the conscience (Bavinck)? Or does God through the conscience sanctify the sovereignty, and thus the free existence, of the various social spheres (Kuyper)? Which determines which? Perhaps neo-Calvinism at its root truly embraces both—that is, that our consciences and social contexts create feedback loops into one another. That would be intriguing and compelling. Unfortunately, Brock and Sutanto, in favoring Bavinck over Kuyper, obfuscate this apparent difference between them and thus neglect to explore the fascinating implications for appropriating both of their neo-Calvinist theological insights in addressing the question of conscience today.

This, then, leads to the third and most severe defect. To the extent that Bavinck’s views are presented as the sum of “Kuyper and Bavinck,” even where they conflict with Kuyper’s, Brock and Sutanto fail to accurately represent Kuyper’s views, and thus misrepresent neo-Calvinism as something bound by a view common to both thinkers. To give another example, in exploring the relation between science and worldview, they quote Bavinck at length and then summarize his position that “to build a worldview, one has to begin with science.” Yet this is the opposite of Kuyper’s view. For Kuyper, one’s worldview dictates the starting point of all scientific inquiry. Thus, as the authors note, despite this contradiction Kuyper distinguished between “normalist” science that mistakenly denies the reality of sin and “abnormalist” science that correctly accounts for it. Furthermore, Kuyper insists that only by a common worldview can scientific investigations across the faculties of a university contribute to a single whole. A shared worldview alone makes individual scholars into a scientific organism—namely, a university in substance rather than mere form.

And so I’m conflicted. Neo-Calvinism is the best introduction to the theology of Kuyper and Bavinck available. But on several points, Brock and Sutanto fail to accomplish their own stated goal. So I recommend it … but only until something better comes along.