From very nearly the beginning, Christianity has wrestled with the question of the body. Heretics from gnostics to docetists devalued physical reality and the body, while orthodox Christianity insisted that the physical world offers us true signs pointing to God. This quarrel persists today, and one form it takes is the general confusion among Christians and non-Christians alike about gender. Is gender an abstracted idea? Is it reducible to biological characteristics? Is it a set of behaviors determined by society? Or is it something more?

Among the many subjects Christian apologist, novelist, and scholar C.S. Lewis addressed was, surprisingly, gender. His imaginative and coherent conception of gender as a revelation of God holds promise for the many confusions in our day.

It may come as a surprise to hear that C.S. Lewis had many thoughts on these questions. In fact, woven throughout his works, Lewis offers us a coherent, orthodox, and imaginatively satisfying vision of gender, one in which gender is a unique revelation of God—an apocalypse—and a powerful sign of reality itself.

Lewis, a master of Renaissance literature (and through it, of the late medieval period and antiquity), allowed his imagination to be formed not by the convulsions of his era but by the slow developments of millennia. He writes from deep within a realm many of us struggle even to enter, let alone explore: that of the Christian imagination, in which every single element of reality is at once itself and also a profound sign of God’s nature.

I have hesitated for a long time before writing about gender from a Lewisian perspective. It is perilous to bring a past thinker into discussion of a contemporary issue. As Lewis himself knew, these topics are best approached through the imagination. Rather than this essay, it would be more effective to write a poem or a song or a story about gender and the Christian imagination. That, after all, is what Lewis did.

But elucidating an imaginative vision, as Michael Ward does for Lewis’ thought in Planet Narnia, can be helpful. For many of us, the landscape of the Christian imagination is so far away that we need guides to point even to the trailhead. I hope here to point the way to that trailhead, where Lewis himself is waiting to lead us into the foothills of a realm in which physical realities, like our bodies, are signs revealing the nature of God.

Ideas Are Not Enough

In Lewis’ imagination, there is no such thing as an “abstract idea.” In Planet Narnia, Michael Ward writes that Lewis believed that “to prefer abstractions is not to be more rational; it is simply to be less fully human.” An idea must have an associated “sign,” a body or a word or a relation, something we apprehend through our senses. We know reality through these signs, which come through our senses into our imaginations and shape how we live.

Gender is a unique revelation of God—an apocalypse—and a powerful sign of reality itself.

Lewis wrote about this in The Abolition of Man: “In battle it is not syllogisms that will keep the reluctant nerves and muscles to their post in the third hour of the bombardment. The crudest sentimentalism … about a flag or a country or a regiment will be of more use.” The idea—here, of loyalty—is meaningless and cannot move us to action unless it captures the imagination through a tangible sign.

But imagination is shaped through the most subtle of movements. A deft stroke here, an obscure tale there—a nudge, a smile—thus a soul is shaped, a soul that either welcomes with joy the fullness of reality (material and spiritual) or shies away from it. That, Lewis reminds us, is what being alive is all about: it is our chance to learn to exist in a happy, correct relation to reality. The physical world is an array of signs, indicating how we are to live.

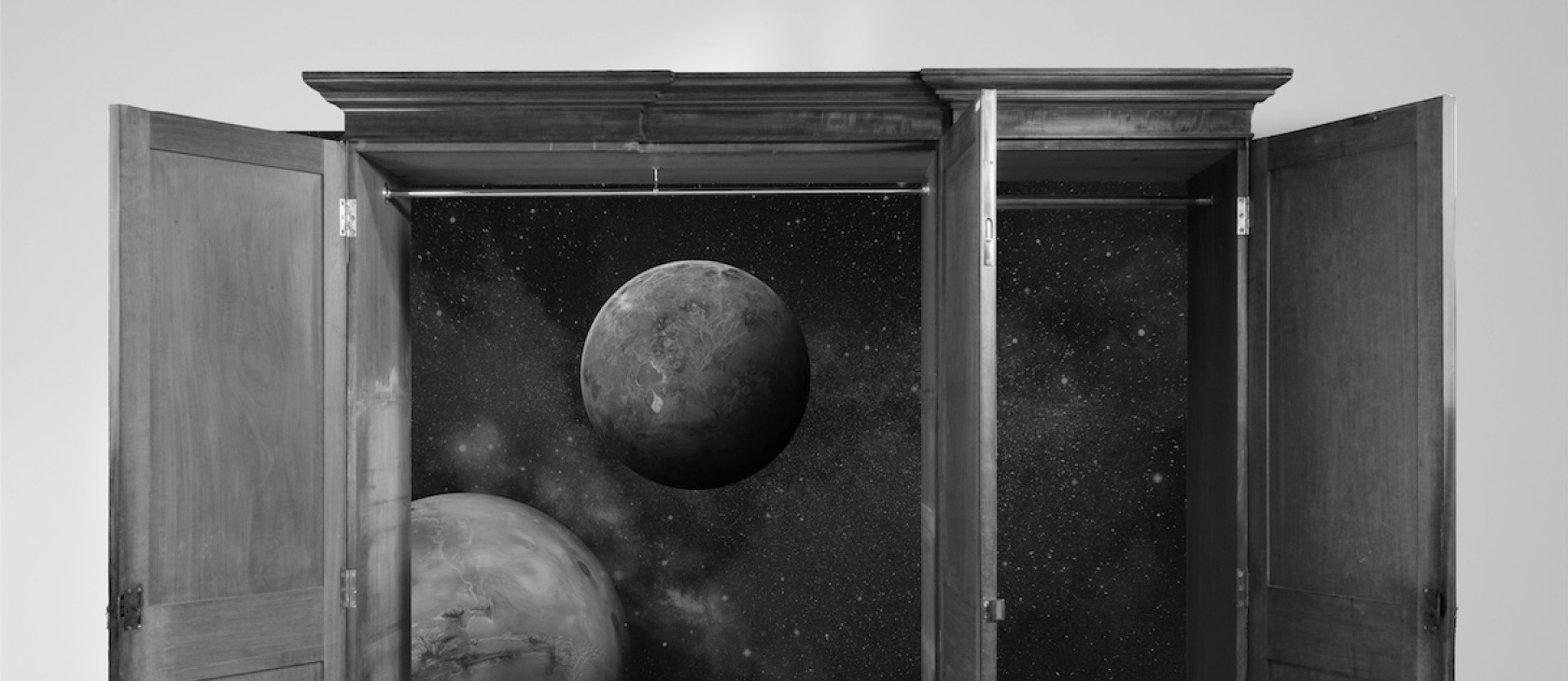

This is not to say that the physical world is “merely” a sign. Just as Lucy’s wardrobe was both a properly functioning piece of furniture—pleasing to the eye and useful for containing clothes—and a way into another world, created things are simultaneously themselves and more than themselves.

The reigning notion of Lewis’ work is that the inside is bigger than the outside. The signs that make up the created world point to realities much greater than themselves. The wardrobe is a best-known instance, but we see the motif repeated over and over, from the valley of Psyche in Till We Have Faces that holds a god bigger than the world to the barn in The Last Battle that opens into paradise.

That is how imagination works: it allows us to house great things inside small ones, just as God has housed eternal souls in physical bodies and Himself in a crumb of bread. The great truth revealed by Christianity is that both physical reality and spiritual reality are eternally significant. All God’s works are doors to Him: meaningful in themselves but also portals to spaces bigger than the world itself. Everything from the patterns of the stars to the shape of our bodies points us “further up and further in” to the heart of God.

The catch, though, is that we can misread—or even misuse and destroy—these signs. That includes the great sign of gender.

What Gender Isn’t

So, in Lewis’ imaginative landscape where physical realities are indications of spiritual realities, what is gender?

On the outset, there are two things it most certainly is not.

Biological sex and gender are not interchangeable, yet they are impossible to separate.

First, it is not interchangeable with sex. By “sex,” I mean “biological sexuality.” I mean it in the sense that we all have sex, even virgins, even the impotent and disfigured. Sex, for each of us, is an outward sign—for ourselves and for the world—of a deeper reality we participate in. Simultaneously, body parts like genitalia matter but they are not ultimate. Genitalia indicates, reveals, something Realer about a person; but changing the sign does not change the Reality. We are not limited to our biological sexuality, but neither can we separate from it.

To illustrate how distinct gender is from sex in the imaginative world Lewis writes from, consider this: in thousands of lines of poetry written over his lifetime, John Milton, a poet Lewis studied deeply, uses the genderless pronoun “its” only three times. Almost without exception, Milton uses either “his” or “her.” He views everything—mountains, air, mind, fruit, joy, everything—as either masculine or feminine. But obviously, not everything is sexed.

Lewis explores this distinction in Perelandra, when the hero, Ransom, encounters the angelic beings that govern Mars (Malacandra) and Venus (Perelandra). He says, “The two creatures were sexless. But he of Malacandra was masculine (not male); she of Perelandra was feminine (not female).” Lewis believes that gender—masculinity and femininity—can exist separate from sex (sexless beings have gender); but sex cannot exist separate from gender, for gender is behind (“at back of,” George MacDonald might say) sex. The physical body is the sign that reveals the thing beyond it: gender. And in its turn, gender too is a sign, revealing … well, we’ll get to that later.

It may seem, with this distinction, that Lewis is giving ground to those who assert that it is possible for a person to exist in the wrong body. He is not. Biological sex and gender are not interchangeable, yet they are impossible to separate. To use a Lewisian image, biological sex is the door, and gender is the house and grounds beyond. You cannot separate the door from the house; you cannot claim that the door opens somehow into the “wrong” house. The door is part of the house. Damaging or blocking up the door does not alter the house. It only makes it more difficult to get to.

So sex is part of gender, but not the only part. No one would reduce a house to its door. A door is practically two-dimensional; it is significant yet fleeting, a plane to be crossed as we enter the three-dimensional house, in which there is music and laughter and feasting and fire.

Sex is like this. It is a temporal sign of gender. In the passage in Perelandra, Lewis goes on: “Gender is a reality, and a more fundamental reality than sex. Sex is, in fact, merely the adaptation to organic love of a fundamental polarity that divides all created beings” (emphasis added). Biological sexuality is only one sign pointing us toward the reality of gender; the distinction between the sexes is one manifestation of a greater distinction that runs all the way up the Great Chain of Being.

This is the first corrective. Gender is not sex. The second is this: gender is not reducible to social “gender norms.” High heels for ladies, beer and sports for men—this is the extent of many peoples’ grasp of gender, and it is (literally) damnably misleading.

These norms come to us not from the deep well of tradition but from the relatively recent Victorian period. In Victorian England, social expectations for the sexes became more sharply divided than ever before. It was then that the notions of women as demure and withdrawn from society and men as taciturn world-builders took hold. The older, more nuanced imaginative principles of masculine and feminine, which went far deeper than these social signals, faded until now we can access them only as psychological archetypes—never as the real principles manifested in our physical biological sex. As Lewis writes in The Abolition of Man, “Another little portion of the human heritage has been quietly taken from [us] before [we] were old enough to understand.”

These Victorian notions have a vice grip on our imaginations; even as our society seeks to rebel against them, it takes all its terms from Victorian norms. Look, for example, at the behavior of drag queens, men who posture as women; drag queens “signal” so-called femininity by adopting a few social signals: high heels, large breasts, puffy hair, big eyes. Even as they attempt to transgress “gender norms,” they submit to those norms by assuming, however cheekily, that the essence of femininity is to be found there, and that by adopting those norms, they have somehow adopted femininity itself. But true femininity, as Lewis writes, is far greater than how we wear our hair; it is a principle of reality itself—of God, in fact—and we cannot participate in it just by changing our shoes, or even our body parts. Participating in the Feminine is much more difficult.

Our contemporary idea of “gender norms” has done more than almost anything else to inoculate us against a profound imaginative encounter with real gender.

Mars and Venus

That said, Lewis would find a surprising amount of truth in the saying, “Men are from Mars and women are from Venus.” Within a Lewisian conception of gender, these are the rough outlines. But “gender” is not a restriction; rather, it provides the boundaries within which to flourish. The way Lewis (following Christian thinkers from the past) reads these signs of Mars and Venus reveals a richer, more expansive encounter with the two genders than our contemporary notions.

In medieval and Renaissance literature (and for Lewis), Mars is the great sign of masculinity. In the Mars section of his long poem “The Planets,” Lewis describes this god as “cold and strong,/Necessity’s son.” He writes, “Like handiwork/He offers to all—earns his wages/And whistles the while.” This is masculinity: fierce, hard, strong, a maker, a warrior, “hired gladiator/Of evil and good.” In Perelandra, Ransom says that Mars, called here Malacandra,

seemed to him to have the look of one standing armed, at the ramparts of his own remote archaic world, in ceaseless vigilance, his eyes ever roaming the earth-ward horizon whence his danger came long ago. “A sailor’s look,” Ransom once said to me; “you know ... eyes that are impregnated with distance.”

Speaking of Venus, the feminine, in “The Planets,” Lewis writes that “her breath’s sweetness/Bewitches the world.” The “reign of her secret sceptre” shows in all the world’s beauty, “In grass growing, and grain bursting,/Flower unfolding, and flesh longing,/and shower falling sharp in April.” Ransom, meeting this goddess as Perelandra, contrasts her with Malacandra:

But the eyes of Perelandra opened, as it were, inward, as if they were the curtained gateway to a world of waves and murmurings and wandering airs, of life that rocked in winds and splashed on mossy stones and descended as the dew and arose sunward in thin-spun delicacy of mist.

Ransom struggles to articulate how he knows that these Malacandra and Perelandra are masculine and feminine when they have no sexual characteristics. Here, in this passage describing Malacandra and Perelandra, Lewis summarizes his idea of gender:

Whence came this curious difference between them? He found that he could point to no single feature where the difference resided, yet it was impossible to ignore. … [Ransom] has said that Malacandra was like rhythm and Perelandra like melody. He has said that Malacandra affected him like a quantitative, Perelandra like an accentual, metre. He thinks that the first held in his hand something like a spear, but the hands of the other were open, with the palms towards him. … At all events what Ransom saw at that moment was the real meaning of gender.

Here we have the elements of an imaginative grasp of gender: the masculine as rhythm, quantity, weaponed (as Lewis describes it in Till We Have Faces), defending; and the feminine as melody, accent, openness, offering. The “spear” in Malacandra’s hand is connected, of course, to phallic symbols, but it is in reverse of our usual ways of thinking about such symbols. The spear is not a phallic sign (for that would make sex the mystery behind gender); rather, the phallus is a spear sign. It is a physical symbol that points us to masculinity’s “something like a spear,” that innate guardian movement that is masculinity. This inversion—seeing sexual characteristics as signs of gender, rather than the other way around—is the Lewisian imagination at work.

This is where an imaginative grasp of gender is quite liberating to minds accustomed to gender as Victorian social behavior. Here is one example: as Michael Ward explains in the Mars chapter in Planet Narnia, Mars, the archetype of war and the masculine, originated as a god of farming. He was the god of the springtime. March is named after him not only because it was the season when martial campaigns could begin but also because it was the season to start preparing the ground for sowing. Masculinity has a guardian element, but also a gardener element. By understanding the symbol in all its richness, men who delight in nurturing and cultivating can see these as deeply masculine impulses, too.

The same is true of Venus: she is stereotyped as the goddess of sex, love, and desire, a passive goddess who simply emerges from seafoam and does little besides sow chaos. But her nature is more complex than that. The pagan Venus is utterly generative; as Lewis says, she is self-fertilizing. She needs no male to make her productive. In the Christian imagination, as Lewis writes in Spenser’s Images of Life, some medieval philosophers used “Venus” as a name for God. Femininity, in this conception, is far from the passive thing we find in the Victorians or even the primal chaos described by some contemporary psychology (which, we hear, must be subdued and shaped by masculine order). The Christian symbol of Venus transcends all this, situating ultimate order—the Order of Creation—in the Feminine, which does not merely receive life but self-generates it.

These Lewisian conceptions of gender are imaginative, not diagnostic. The clear-cut distinctions we try to establish between male and female activities are less important than trying to grasp masculine and feminine essences, these principles that govern the created world. Men can be caretakers and be deeply masculine; women can be bold, inventive creators and be deeply feminine. Gender is not strictly about what we do, per se, but how we do it.

This is where our contemporary culture gets tripped up, for we can only act through our bodies—which carry with them a biological sex. Anyone in a female body must come to terms with her fundamental association with the Feminine; anyone in a male body must come to terms with his fundamental association with the Masculine. The ways of doing that are manifold, but it must be done.

Our bodies, with their biological sex, are the sign of how we, as individuals, will relate to reality. Even by changing those signs, we cannot change what they tell us about reality. We can only seek to read them rightly.

Reading the Signs

In The Abolition of Man, Lewis reminds us,

Until quite modern times all teachers and even all men believed the universe to be such that certain emotional reactions on our part could be either congruous or incongruous to it—believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence or our contempt.

In other words, some emotional responses to the signs we see in this physical world are right, and some are wrong. There are correct ways to read the signs and incorrect ways.

So how do we read the signs of gender? Lewis offers some wisdom on this, though most of it is given through literature, rather than instruction. His books are full of examples of masculinity and femininity, both true and distorted, and throughout we gain a sense of what it really means to fully inhabit one’s gender.

Here are just a few examples.

That Hideous Strength

“Have no more dreams. Have children instead,” Lewis has a character say in That Hideous Strength, speaking to Jane Tudor Studdock, an aspiring academic whose marriage has proved disappointing (and who has been plagued by prophetic dreams). This line might lead a reader to believe that Lewis was condemning women for having ambitions. The correct reading leads to a quite different conclusion.

Lewis made no sweeping condemnation of women’s ambitions to public life. Rather, throughout his career he encouraged female scholars who showed promise, including philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe, whose critiques of Lewis’ Miracles pushed Lewis to rewrite large portions of the book. The line commending Jane Studdock to motherhood is unique to Jane; Lewis recognizes that each woman’s life, just as each man’s, will look different. For her own good, Jane is not to seek the literal nightmares that plagued her, but neither is she to follow the specious “dreams” of academic life—dreams for which she was simply not suited. Jane does not truly love academia; her thesis topic, described at the beginning of the book, is unoriginal. She pursued academic life because in it she found friendship and joy; now she’s using it as an escape from her marriage and call to motherhood.

Jane is not alone in being asked to abandon her false dreams. Mark, her husband, is even more in thrall to dreams; nearly until the end of the book, he lives in a fantasy about himself and his own qualities. He is desperate to assert himself as dominant, powerful, untouchable. His idea of masculinity is entirely out of balance; he has abandoned his masculine roles of guardian and gardener. As a result, he is emasculated and miserable. Jane and Mark are only able to find peace and joy when they both begin to act in accordance with their genders. Jane must truly welcome Mark into her life, while Mark must learn that he is not entitled to her love but must guard and cultivate it every day.

These actions—these turnings of the soul toward each other—are not reducible to Victorian gender roles; Jane is free to make a life that matches her temperament and talents, but she must really welcome and honor Mark in that life. She cannot keep him at arms’ length. She must allow him to enter and change her. Mark, in his turn, need not become a strong silent masterly type, but he must find ways to actively guard and grow the richness of their shared life.

That Hideous Strength also underscores the reality that gender goes beyond marriage and family activities by depicting characters who are single (the Director) or barren (the Dimbles) as fully inhabiting their gender. Mother Dimble cannot bear children, yet she embraces her feminine nature and becomes a mother to everyone she meets. The Director is celibate, yet the other characters encounter him as profoundly masculine. It is clear that Lewis, in agreement with the Christian tradition, recognizes that being married or being a parent is neither a requirement nor a guarantee of a real embrace of one’s God-given gender.

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe

“Battles are ugly when women fight.” This line from The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe could come off as denigrating women’s abilities. But the rest of the Narnia books disprove this.

First of all, both Lucy and Susan receive weapons from Father Christmas, implying that there are appropriate times for women to bear arms. Lewis underscores this in the other Narnia books: in The Horse and His Boy, Queen Lucy fights with the archers in a battle against the Calormenes, and Aravis is a noted swordswoman, confident atop her warhorse. In The Last Battle, Jill is the best archer, which garners praise, not condemnation. Battles certainly are ugly when women fight, but they are ugly when women do not. Father Christmas’ words seem to be an absolute prohibition, but in fact they’re a protection; after all, these are little girls.

Interestingly, Peter and Edmund are not given the same protection, but they are given another. Remember what happens to Lucy and Susan instead of the battle. Far from being tucked away and shielded, the girls become witnesses to a scene even more brutal than the battlefield: the murder of Aslan. The girls are protected from witnessing the horror of war; Peter and Edmund, equally, are protected from witnessing the death of Aslan.

All four of the children, male and female alike, come face to face with evil, ugliness, fear, and death. None is spared. But they confront these things in different ways, ways suited to their temperaments and natures, which include their gender.

The Last Battle

“[Susan] is no longer a friend of Narnia.” In The Last Battle, Susan, unlike the rest of her family, does not return to Narnia or continue on into Aslan’s Country, because she has become “only interested in lipstick, nylons, and party invitations.” This moment has troubled many readers, including Phillip Pullman, who created His Dark Materials as an anti-Narnia, and J.K. Rowling, who became disenchanted with the whole world of Narnia by Susan’s fate. Pullman and Rowling read this passage as saying that Susan is banned from Narnia because she has grown up and learned about sex, which they find deeply unfair.

They both misread the passage. Susan is not excluded from Narnia because she grows up and becomes interested in feminine things. The Last Battle names two causes for her fate: first, she convinces herself that Narnia is not real, and second, she refuses to grow up. These reasons are really one and the same. Susan stops believing that the physical world is a true sign of another world. She disbelieves the very evidence of her senses, which tell her that her experiences in Narnia were real and which also ought to tell her that there are more important things than nylons and party invitations. Growing up is essentially the process of reading the signs of the world ever more deeply and truly, and Susan refuses to do this.

Susan lives in a netherworld between a feminine childhood and a feminine adulthood. She adopts the lowest outward indications of femininity but refuses to become a mature manifestation of the feminine. She reduces femininity to the shoddy external signs of young womanhood. Her body has ceased to be a true sign of the feminine: generative, sacrificial, mothering even in childlessness. For that, she is barred from Narnia. (As a note, Lewis indicated in a letter to a concerned young reader that Susan’s story does not necessarily end in damnation, adding that that, however, was not his story to tell.)

Till We Have Faces

In his last novel, Lewis gives his most finely grained treatment of gender, and the feminine specifically. Orual, the ugly sister of Psyche, spends the book trying to suppress her feminine nature. She participates in many activities perceived as masculine—ruling, fighting, negotiating—and eschews more “feminine” activities, like marriage and childbearing.

But, as she discovers at the end of her life, her feminine nature is inescapable. All her efforts to abandon her femininity only lead her deeper into femininity. Whether she veils her face or shows it, whether she fights or does not fight, whether she rules or submits, she is feminine. Both her sins and her virtues spring from her nature as feminine; she risks damnation by feminine means but is eventually saved by accepting her femininity—and God’s masculine relationship with His creation, which we’ll discuss in a moment toward her—as a gift. After her death, this childless virgin is remembered as a beloved mother of her people.

The Apocalypse of Gender

In this Lewisian world where physical realities are true signs of spiritual reality, where the inside is bigger than the outside, and where we are always being pushed further up and further into the ever-expanding reality that is God, what is gender?

Here as an attempt at an answer: gender is a distinctive way of manifesting one of God’s various relationships with His creation. Each gender is a revelation—an apocalypse—of some side of God’s love.

The masculine is a revelation of God’s great hunter and warrior love, vigilant and protective, which existed before the Beloved and knows what existence without the Beloved is like. This is the love that gave creation the freedom to fall, and the love that dared redeem it. This is the love that fixed a tree on the borders of all the worlds and hung Himself upon it.

But there is another love: the feminine love, “world-mothering” (as G.M. Hopkins calls it), which saw a void, encompassed it, and brought order and beauty and abundance from nothing. This is the love that bears the world, that longs to gather everything under its wings, the love that tore itself open, abandoned itself utterly, in the labor of bringing forth new Life.

You will notice, of course, that both these loves are fully manifested on the Cross. In Christ, who is fully God, the apocalypse of both genders is present.

Through revelation history, God predominately shows Himself as masculine. For Lewis, this is not allegorical.

Some readers may draw back from this, but they need not. Throughout sacred Scripture, God primarily interacts with us through masculine signs. But there are hints of another way, a feminine way. Christ speaks of Himself as a mother hen; in Hosea, God speaks of Himself as a mother bear, and in Deuteronomy, a mother eagle. The mothering nature is as much a part of God as the fathering nature.

However, as Lewis wrote in an article called “Priestesses in the Church?” (which all Christians should read in full), “Christians think that God Himself has taught us how to speak of Him.” Through revelation history, God predominately shows Himself as masculine. For Lewis, this is not allegorical; these masculine pronouns and images are true signs. Through language, God reveals Himself to us—to all of us, male and female—as a bridegroom, a father, a guardian gardener. God is not limited to the masculine, certainly, but His revelation as masculine teaches us truths about how we are to live in relation to Him. Lewis says that to ignore the way God speaks to us requires us to ignore the signs, to follow the sin of Susan, to believe “that sex is something superficial,” and that our bodies tell us nothing about reality itself.

If we are going to begin to grasp the mysteries of gender, we must follow Lewis’ faith in signs. We cannot pick and choose; we cannot accept the meaning of the sign but reject the sign itself. What I mean by this is that we cannot embrace gender as a revelation of God’s love if we reject the signs by which that revelation occurs, of which the physical body and the language of Scripture are the most significant.

Christianity offers us a gift: the belief that both the physical world and the spiritual world are vitally important. The spiritual world is the realm in which God can be experienced directly. For that reason, it is ultimate. Yet the physical world is where we determine how that experience of God will be realized. Christianity teaches that no one can be saved after death; even Purgatory is open only to those whose souls are already saved. Our lives on earth, our habits of thinking and acting, our openness or closedness to God in all His revelations—including the revelation of gender—these things decide how we will experience God in the apocalypse that is death and eternity: as fearful and incomprehensible, or as an unfolding infinity of Love.