National Conservatism’s Statement of Principles, released in 2022, generated a flurry of interesting conservative writing on the relationship between religion and public life thanks to its robust endorsement of a “public religion.” And since that time, several books and articles have been published by people sympathetic to the national conservative movement embracing the “Christian nationalism” identifier initially employed as an epithet from the left.

There have been calls recently for a more robust infusion of religion, particularly some form of Christianity, into the body politic and public policies. But we’ve been down this road before. A confusion of state and church results in neither doing its job well.

Descriptions of this public religion differ from author to author, but most accounts argue that there is a distinct American identity structured at least in part around Christianity or Protestantism and its “moral vision” (to use the Statement’s language). Moreover, government ought to take an active role in promoting and (since it has decayed over the years) reviving this American religion. This might mean laws that encourage church attendance or punish blasphemy. But advocates mostly focus on political rhetoric, symbolism, and religious content in public education and government institutions.

The plurality of American Christian denominations is unavoidable, of course, so most of these calls (exempting the distinctive and politically marginal Catholic integralists) are not aimed at promoting a particular church but rather Christianity or Protestantism broadly construed. Yoram Hazony, in Conservatism: A Rediscovery, argues that “the traditional religion (or religions) of the nation” is to be favored; Josh Hammer has similarly spoken of “ecumenical integralism.” And Christian proponents will generally refer broadly to a Christian or Protestant cultural foundation. Without getting into too many theological details, they argue, our politics needs more God-talk.

One of the most common defenses of this vision is historical—pointing back to American origins and the European Protestant experience that forms the context of early American political and religious life. Religion and politics were never entirely separate during this time, with dynamic interconnections in just about every Christian country. The modern expectation of religious neutrality on the part of the state is a new phenomenon. In fact, many often argue, such a separation is impossible in that the state will always have some religious or quasi-religious preferences that will be reflected in law and policy—why not make them our own?

But in more ways than one, the devil is in the details. Big-picture talk of public religion avoids the question of the particular tasks of church and state and the value of each performing what is distinctive to it. The most common complaint against “Christian nationalist” public religion is that it is a threat to the American political system. But a quick glance at history would show that American democracy is more than capable of handling a public “Christianity.” The real danger is what American democracy does to the faith.

The State Church

For centuries after the Reformation, when government sought to promote Christianity, it did so by the legal establishment of a specific church with a specific confession. To 21st-century eyes, establishment seems like the complete mixing of politics and faith. But that is not entirely the case. For all the many overlaps, the establishments were clearly not intended to challenge a fundamental principle of Protestant church-state teaching: that the task of the Church and the task of civil government were very different, and that the two, in the words of the Augsburg Confession, “must not be confounded.” The Church’s proper task was not the direction of earthly kingdoms but the preaching of the gospel and the administering of the sacraments. The civil government’s task was not to teach the scriptures or provide spiritual fulfillment, but to promote peace and good social order. This distinction of tasks was meant to be an assurance that the gospel would not be corrupted either by political rulers with ulterior motives or by a church distracted by the pursuit of temporal power.

The modern expectation of religious neutrality on the part of the state is a new phenomenon.

The traditional establishment was, in one sense, the recognition by the state of an earthly source of authority outside itself and submission to it within its rightful sphere. The established church was a specific institution that could, practically speaking, be treated as “the Church” for national purposes (with carve-outs and exceptions possible for dissenters). So the confessional state could be seen as distinctively Christian while remaining in its prescribed role in part because it was not pledging itself merely to furthering a generic idea—an abstract “Christianity”—but to this specific institution with its specific confession and its clergy to defend it.

The prince, king, or government more broadly could symbolically support the established church, contribute public money to its coffers, tie legal rights and privileges to membership, and in some cases even play a role in elevating bishops. But such responsibilities could be understood as dealing with externals. The established church itself was still the authority tasked with teaching and maintaining the substantive content of the faith. The state, it was thought, would reap the side effects of a faithful and religious people and could support the church insofar as its strength was seen as important to civil peace, public morals, and unity.

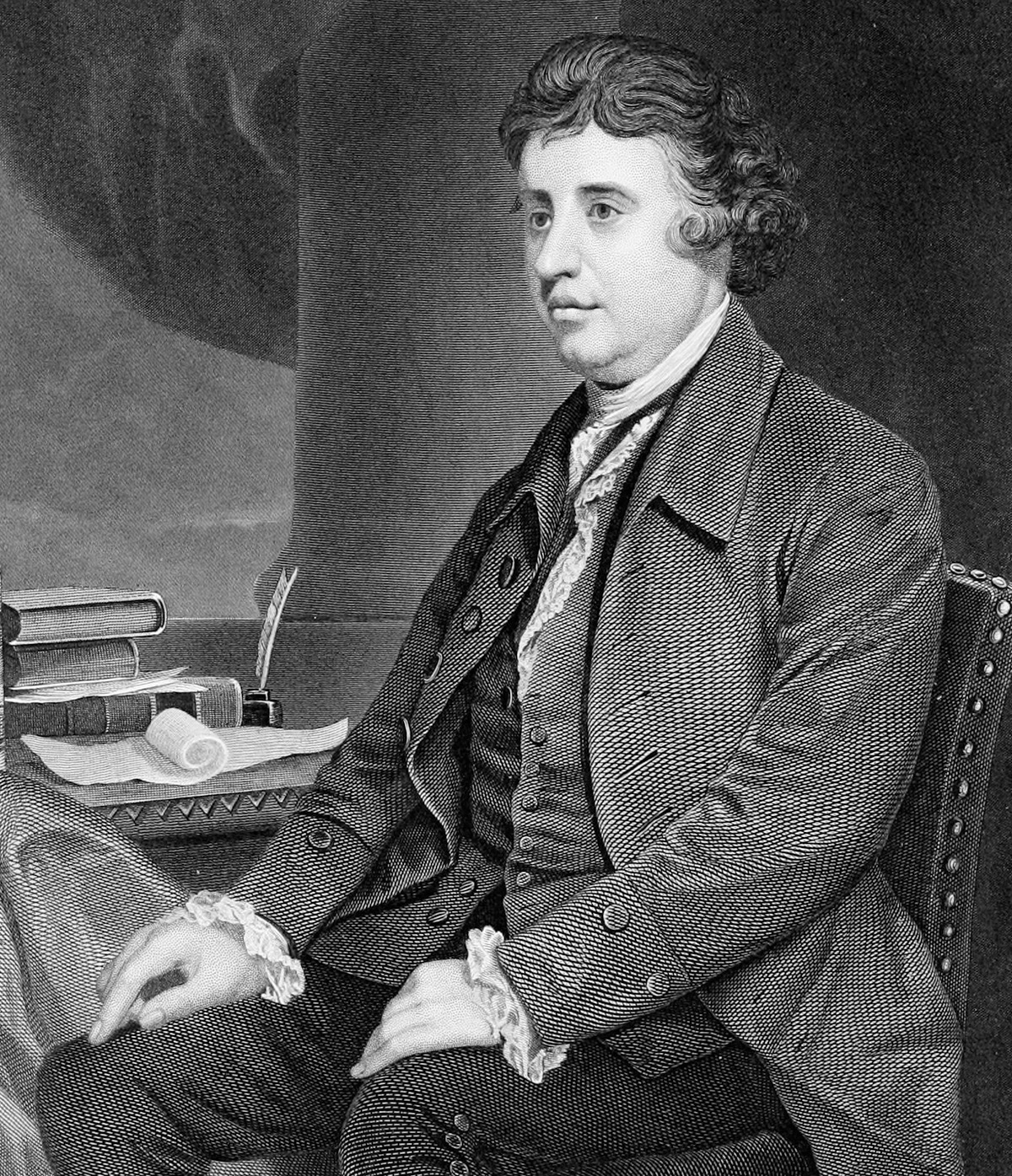

It was this essential distinction of tasks that could allow someone like Edmund Burke to simultaneously affirm that “religion is the basis of civil society”—and even speak of a “consecrated state”—while still maintaining that “politics and the pulpit are terms that have little agreement.” It was the “confusion of duties” that was most to be avoided.

To be sure, the established churches certainly offered plenty of opportunities for confusion, and much civil involvement in the national churches was countenanced through incredibly subtle distinctions; it cannot be said that the separation of tasks was always maintained in practice. And the present state of just about every established church in the world today shows that it was hardly a bulwark against an encroaching modern liberalism. But at least in theory, the arrangement left the substance of the Christian gospel in the hands of the Church.

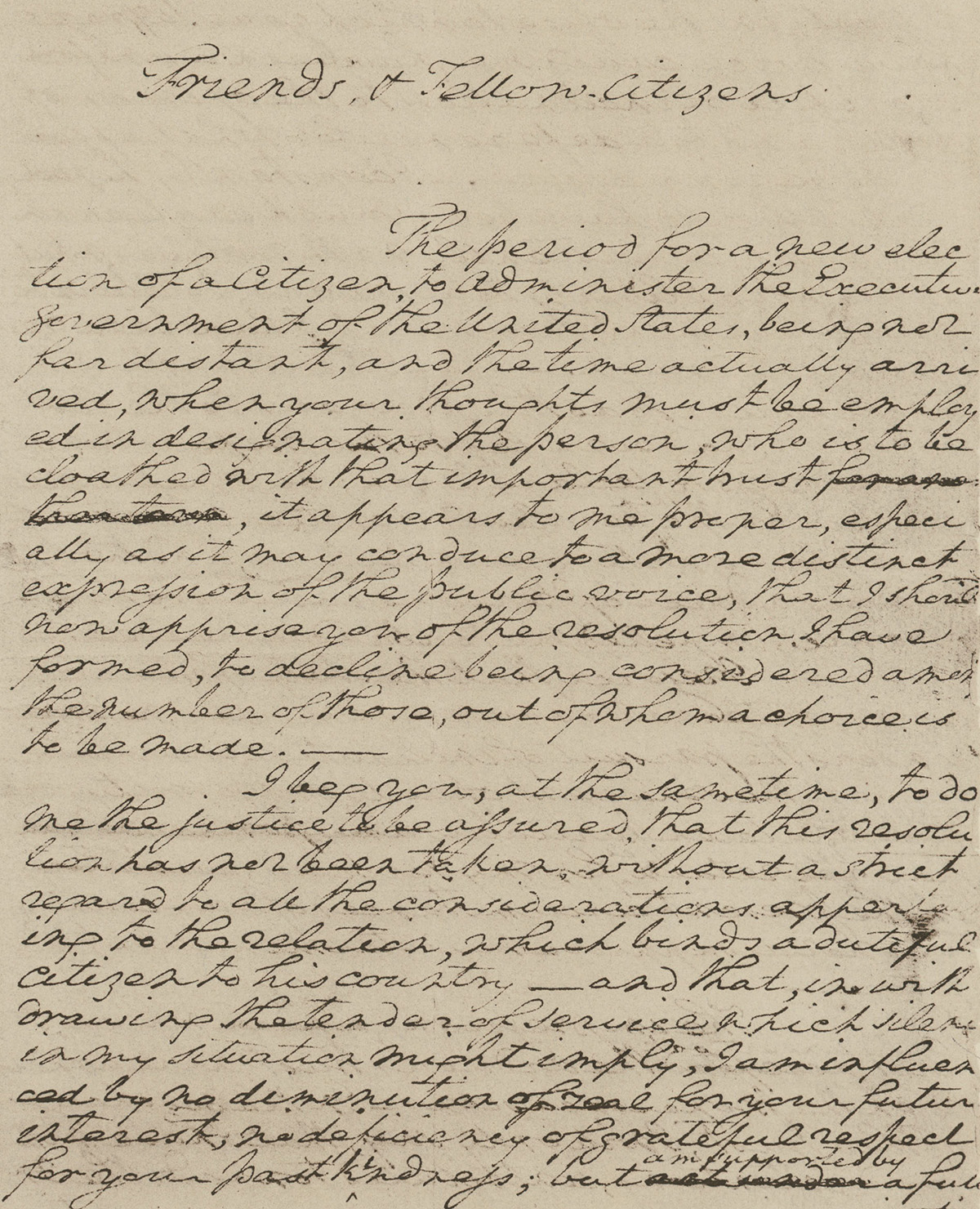

The possibility of this sort of straightforward establishment in America was short-lived and localized. There was never the kind of religious unity that could have allowed for a distinctly American identity to form around a specific national church, and the establishments that existed locally were, as religious diversity rapidly increased, quickly transformed into moderate, “quasi-establishments” that legally favored and rhetorically utilized Protestantism or Christianity writ large. These, in turn, eventually gave way to a system of official neutrality among sects, but robust religious political rhetoric that presented Christianity as an essential aid to public morality and national identity, along the lines of Washington’s Farewell Address. Political figures continued to invoke God; activists sought to fit their programs into biblical moral categories (or extra-biblical providential frameworks); public school children recited prayers and learned Bible verses; government bodies opened with invocations.

This sort of lighter religious politics—without any particular confession—seems to be what most of the mainstream national conservatives today would like to return to. And their accounts of history sometimes downplay the difference between traditional establishment and the lighter, more generic promotion of religion, treating them all simply as evidence of a Christian public identity.

But that distinction is vital. The logic and history of this blending of Christianity and politics show that it tends to render the content of the faith a blank canvas on which politicians may ply their trade.

Establishment Without a Confession?

Two realities of American life are critical when considering the likely tendencies of the political promotion of some form of “common” Christianity: mass democracy and sectarian variety. Aside from some occasional online LARPing about an “American Caesar,” few NatCons seem to have any intention of or plan for changing these realities. Given their existence, establishment-lite, without any particular church or confession, takes away almost all possibility that the vital distinction of tasks between church and state will hold in the public—or the Christian—mind. In the absence of any specific church committed to upholding its specific confession and defending itself against corruptions, public religion will inevitably emerge as a kind of synthesis faith formed around the political needs and ambitions of the moment. It might take more traditional or more progressive forms depending on who is using it, but it will be oriented toward political rather than spiritual aims.

Any consciously formed public religion—one that does not emerge from genuine religious unity on fundamentals of the faith but rather from planned public messaging—would be part of a mass political movement and subject to all the incentives at work on such movements. It would have to start with a lowest common denominator: at best, public Christianity would consist simply of whatever is shared by those who identify as Christians (or, if we’re talking about movement conservatism, those who identify as conservative Christians). Divisive or politically inconvenient doctrines must be downplayed in favor of those inclusive enough to sustain a political coalition.

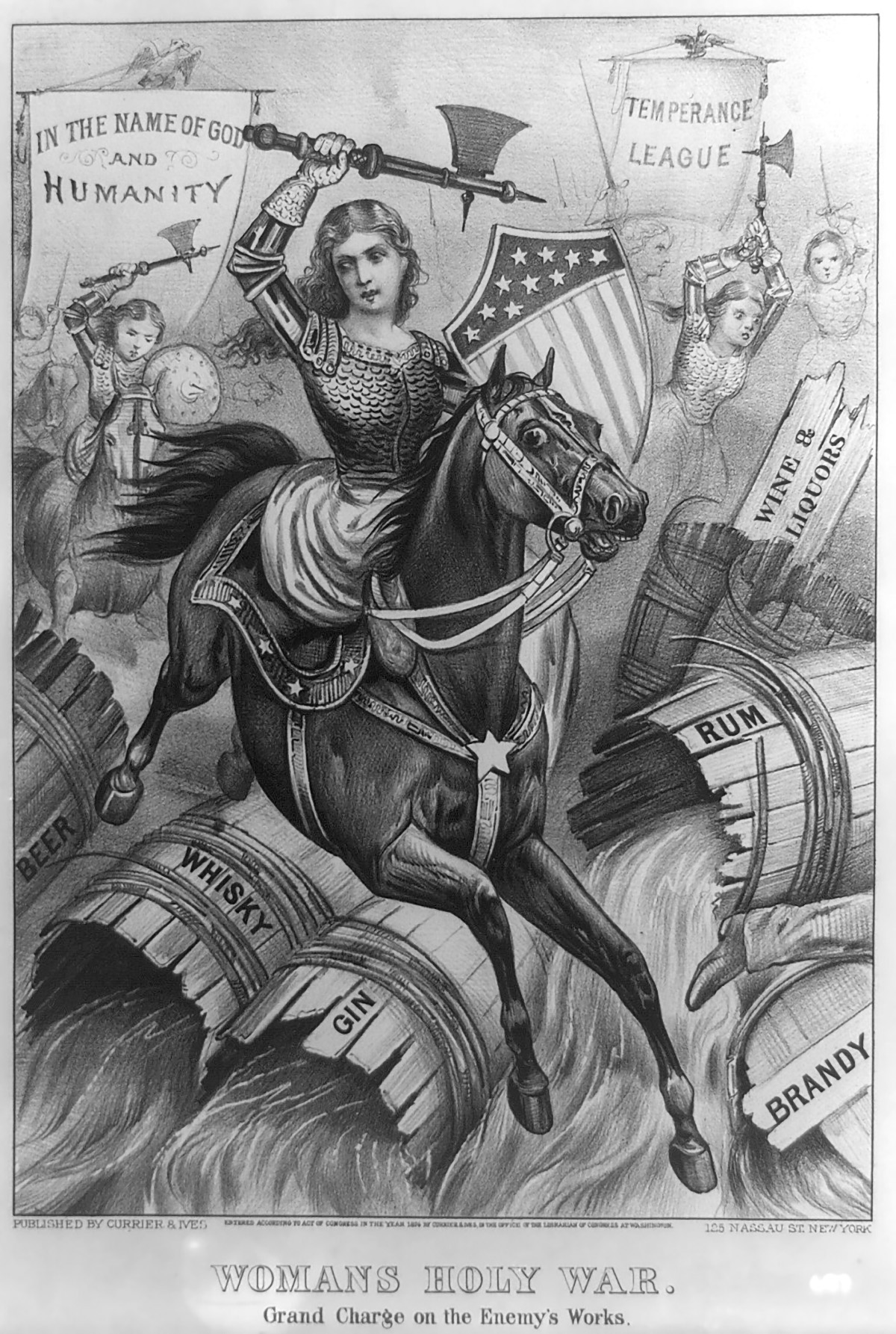

Because it has explicitly political aims (the creation or maintenance of a national identity), this public doctrine would almost certainly be heavily moralistic, focusing on the duties and obligations each has to the collective, or telling us which moral issues “values voters” ought to be most interested in. (Think Prohibition.) Mass political movements seeking to mobilize collective action have little use for the idea that we are made closer to God through faith in Christ rather than through righteous social crusades. And of course, any religion specifically expected to create political unity would naturally place political movements, parties, or nations, rather than the Church, at the center of God’s work on earth.

Divisive or politically inconvenient doctrines must be downplayed in favor of those inclusive enough to sustain a political coalition.

This generic, moralistic version of Christianity, then, would stand as an alternative to creedal, dogmatic, confessional Christianity. It would be a synthesis faith that could cut across sectarian lines, and the incentives of mass democracy would mold it to fit political needs. Like many quasi-religious ideologies on offer, it would claim to fulfill our spiritual longings by channeling it into partisan activity. But unlike other political ideologies and nationalist visions, it would vocally claim the mantle of Christianity. As C.S. Lewis observed in his “Meditation on the Third Commandment”: “The demon inherent in every party is at all times ready enough to disguise himself as the Holy Ghost.”

In contemporary circumstances, a consciously manufactured public religion would therefore do the opposite of what the old establishments in theory aimed at: rather than point subjects to a stable, orthodox Church as guardian of religious truth, hoping merely to glean the beneficial side effects of genuine religious unity, it would appeal to citizens with a contrived political gospel masquerading as Christianity. And given America’s sectarian diversity, this political gospel—preached from state capitols, debate stages, talk shows, and government schools—would have a far more prominent and influential platform than any given church that was mostly focused on the eternal souls of those in its pews. To the extent that such a public religion is pervasive and influential, the churches would have every incentive to conform their messages to it. The state would not be supporting “the Church” as a source of truth that transcends our earthly politics, but rather the many American churches would be led along by the politicians.

Nothing New Under the Sun

If one needs evidence of the likelihood of this scenario, he need only look at American history. The era of nonsectarian “American Christianity” to which today’s conservatives seem to appeal was not a long, stable period of Christian orthodoxy. As Mark Noll has documented, the distinctively American Christianity that cut across denominational differences and appealed to a simply “Christian” or “Protestant” nation wound up taking on the characteristics of the political principles around it, mixing civic virtue with the righteousness of Christ; it was directed toward partisan and national aims; and it steadily marched away from orthodoxy. Even at the time of the Revolution, many appeals to “true religion” consciously papered over points of contention (i.e., fundamental questions of the faith including baptism, the presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper, and the nature of God’s grace to his people) in favor of public morals. The spiritual concept of “Christian liberty” was conflated with civic liberty; invocations of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost gave way to appeals to “the divine being.”

As the 19th century advanced, a decidedly political faith took clearer shape. America—rather than the Church—became the “City on a Hill”; a new “social gospel” defined righteousness not by faith in Christ but by crusading for this or that social outcome; public education taught a safe, moral faith stripped of divisive dogmas that Christians of the past had been willing to die for; the spread of liberty, democracy, and American armies was heralded as the spread of Christ’s kingdom; millenarian nonsense was propagated as support for a Messianic American Cause. There was no shortage of God-talk in public life, but it helped push American churches and their members further away from traditional Christian faith and toward a vague, spiritualized civic moralism.

Though the 20th century saw a salutary, orthodox revival against certain elements of the social gospel movement, American political Christianity showed little signs of reestablishing a firm distinction between a set-apart Church focused on spiritual goods and the civil questions of the city of man. Most public religion—from lofty presidential rhetoric to the daily recitations in public schools—amounted to little more than vague invocations of the Deity, who is recognized as important in some way and expected to bless whatever the present public endeavors happen to be. Unlike Christ’s description of the gospel in Matthew 10, this was a religion specifically crafted to please everyone.

The school prayer at issue in Engel v. Vitale is one such example: “Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our Country.” There is nothing objectionable, but neither is there anything particularly Christian to it. If the NatCons are right, and hold as Hazony does in Conservatism, that government strengthens the things that it honors and weakens the things that it does not, we must ask ourselves whether such rhetoric merely honors the gods of the city. And this is why (as D.G. Hart has outlined in A Secular Faith and The Lost Soul of American Protestantism) Catholics and some confessional Protestants were resistant to or at best unenthusiastic about public school prayer and Bible reading. To them, this was not Christian education.

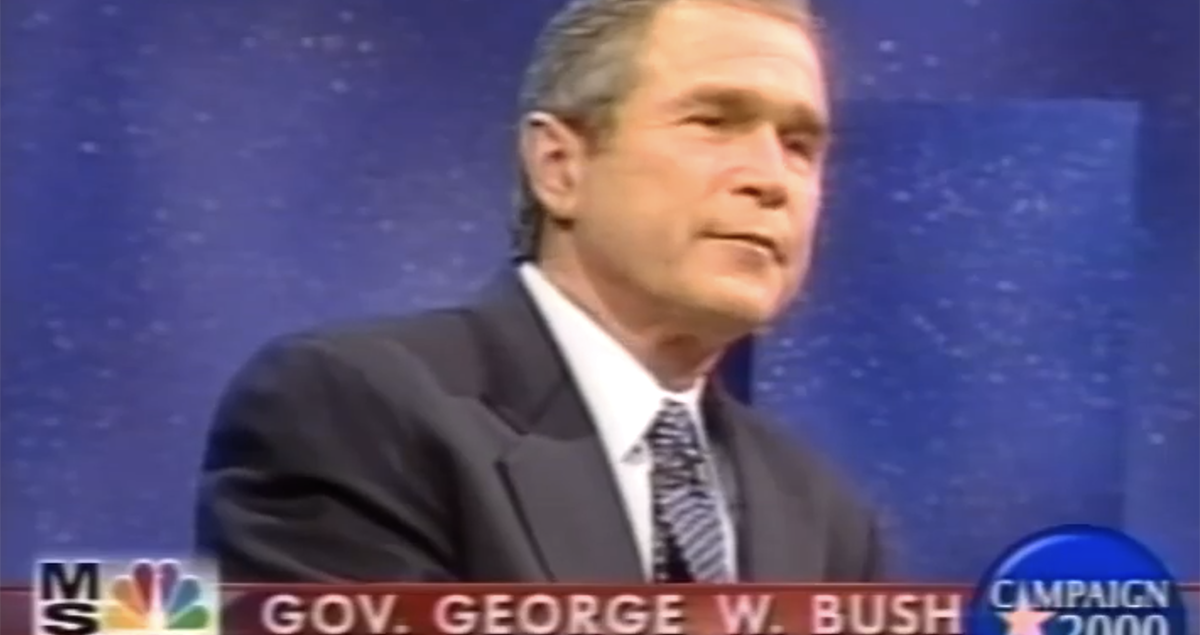

The rise of the “religious right,” moreover, showed that the conflation of spiritual and political goods was not the exclusive purview of liberal Christianity. From the appropriation of practices like the laying on of hands (traditionally a sign of the spiritual setting apart done at ordinations or baptisms) for political candidates, to its susceptibility to millenarian theories about America’s Middle East policy, the movement weaved together Christianity’s spiritual promises with the drive for temporal power. Their moral teachings may have been more conservative, but like the progressives of a different era, they focused much of their attention on an attempt to build a kingdom of this world. When George W. Bush identified Jesus Christ as his favorite “political philosopher” in a 1999 presidential debate, it generated plenty of discussion about cultural divisions, but few asked what it indicated about how American evangelical Christianity presented Christ and the nature of his work.

It’s easy enough to say that this is not the kind of public Christianity that the NatCons are proposing. But the content of any public religion would not be determined by the sincerely faithful think-tankers and pundits who promote the concept. There is no “Christian prince” immune from the influence of mass political movements, and there is no unified national church that could keep the public mind tethered to the fundamentals of the true faith. When politicians or public institutions engage in God-talk, it will be the kind of God-talk people want to hear, whatever that may be.

Moreover, religious indifferentism is already barely hidden in some NatCon writings. In Conservatism, Hazony—an Orthodox Jew who supports a Protestant public religion for America—rather explicitly elevates “a conservative life” over the pursuit of religious truth: “It is obvious that an individual who wishes to embark on a conservative life can do so most easily by taking up the tradition handed down for many generations within his own family, tribe, and nation. This is the way of the human soul, which seeks repentance by returning to the God of his own family.” Likewise, the NatCon Statement of Principles promotes the reading of the Bible “as the first among the sources of a shared Western civilization” and “the rightful inheritance of believers and non-believers alike.” As Dan Hugger observed in the Spring 2023 issue of this magazine, “The Bible as national text is a strange category, somewhat more than literature to be appreciated but a great deal less than the Word of God.”

Sectarian diversity and the forces of mass democracy are realities of American life.

A social life that results from a genuine shared faith is desirable but cannot be manufactured by a national political movement. Anyone concerned with the maintenance of Christian orthodoxy cannot simply desire more public God-talk without some reason to believe it would be spiritually—not merely politically—edifying. While the NatCons and Christian nationalists are correct to observe that separation has not been the historical norm, we don’t live in 16th-century Saxony or Elizabethan England. The Christian churches have existed and adjusted to all manner of political and social circumstances. In states with a high level of religious unity (and a nondemocratic politics), a formal establishment allowed in theory for the possibility of a linkage between church and state without the substance of religion turning into mere political pottage. But those examples are no longer relevant in present circumstances. Sectarian diversity and the forces of mass democracy are realities of American life, and robust religious liberty paired with a nonsectarian state is more beneficial to the task of the Church than a spiritually infused civil morality.

To be sure, governments of modern mass democracies seem programmed to push beyond their proper task and encourage citizens to find spiritual fulfillment in the demands and promises of the collective. In this sense, there is a degree of truth to the NatCon claim that there will always be some form of public religion. But whether directed more by conservatives or more by progressives, this sort of public faith that emerges from the politics of the modern nation-state will always a be human concoction, and it will always be the responsibility of the Church to call out such pretentions as it does all false gods.