I have to begin with a confession. I have found myself developing a bit of an allergy to the increasingly widespread use of the word flourishing. It seems to me to be an elusive term that is being asked to do more work than it has the capacity to do. It appears to have been devised to provide us with a way to talk about the achievement of human ends and happiness while prescinding from stating any of the norms and teleological assumptions that make such discourse meaningful. That is to say, it lets us talk about ends without having any agreement about what the proper ends might be.

Why dredge up the past? Why drag around that dead weight impeding our progress? Perhaps it’s time for historians to rethink the effects of their work on the lives and souls of the general public and find a balance between the discipline of critique and the role of gratitude.

Edited by Darrin M. McMahon

(Oxford University Press, 2022)

To have a “flourishing” life sounds very much like having a fulfilled life, but its non-specificity is troubling. If we are to talk about fulfillment, shouldn’t we also be willing to talk about what it means to fulfill the telos that is peculiar to man? The root sense of the word flourishing is that of a flower that blossoms. But flowers don’t blossom in any old way. A rose is not a carnation, even if it in some cases fails to grow into the rose it was made to be. Shouldn’t we have an anthropology in place that can tell us, in a more normative way, what it means for humans to blossom? Or how we recognize the moral valence of flourishing when we see it? Is it possible to have a “flourishing” criminal enterprise?

Setting these quibbles aside, I must also confess that the intention behind this book and the series of which it is a part seems to me wholly admirable. The series editor, James O. Pawelski, begins the volume with an essay outlining the project, and it is extremely attractive. It is grounded in the contention that the academic disciplines making up what we call “the humanities” are most properly concerned not merely with “the creation of knowledge” but also with the cultivation of virtue (another term crying out for definition, but we’ll let that pass). The result is a series of books, like this one, exploring the potential for a “eudaimonic turn” in the academic work being undertaken in fields such as history, literary studies, music, visual arts, psychology, philosophy, and religious studies. It is an effort generously supported by funding from the Templeton Foundation, and it shows some of the effects of that provenance, as do the various centers of “human flourishing” that Templeton funds have helped establish at universities around the country: there is often a forced and artificial quality to the questions being asked, reflecting the clumsiness of the term flourishing.

But the quality of individual contributions in the case of the volume before us is very high. The editor, Darrin M. McMahon, is an outstanding intellectual historian, whose earlier work on the history of conceptions of happiness makes him a perfect choice for such an undertaking. He has found distinguished contributors who have managed to use the occasion to say meaningful things in response to the somewhat artificial stimulus of the larger project.

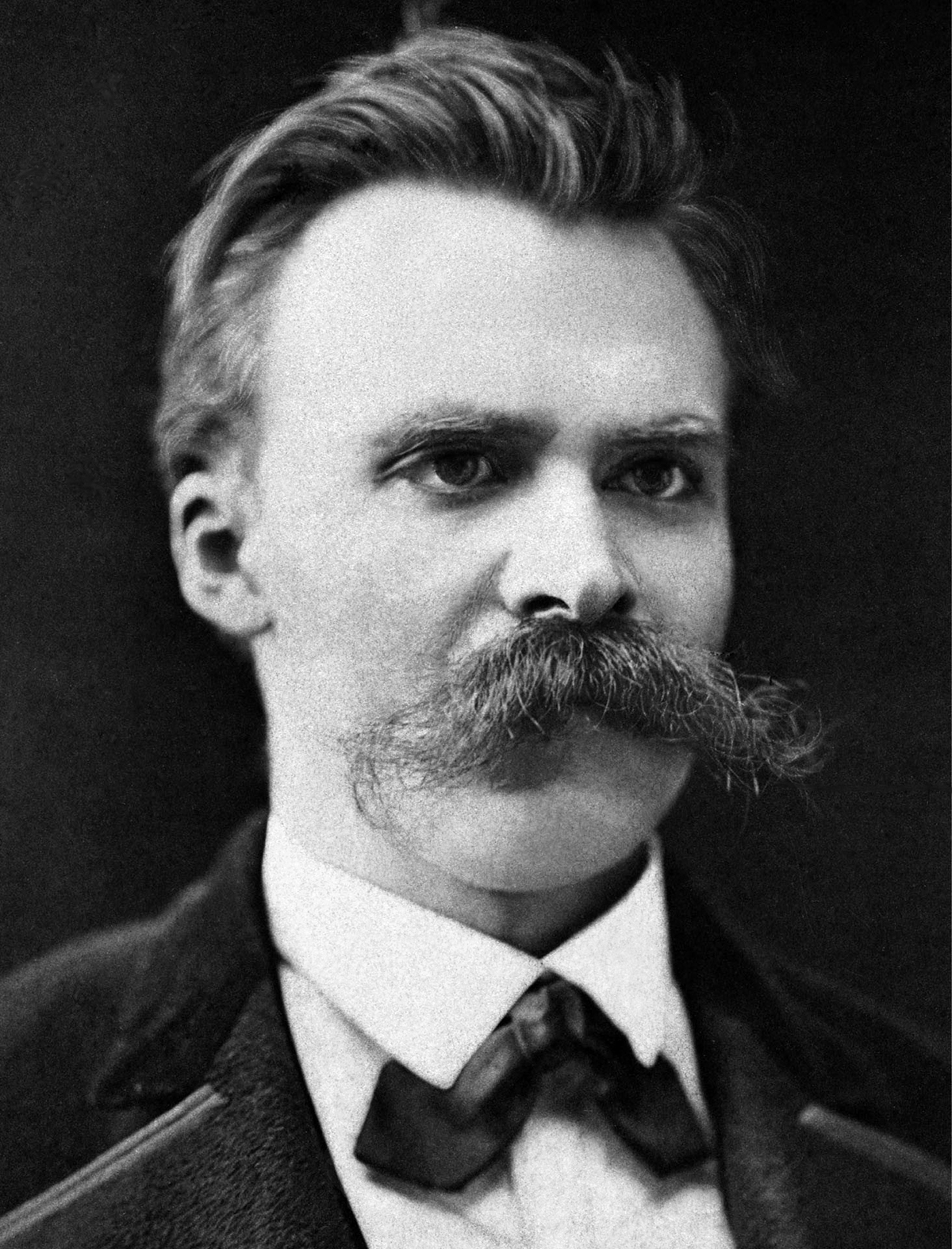

To begin with, McMahon’s introductory essay recasts the Templetonian jargon into something older and better: “What is the value of history for life?” That way of expressing the matter instantly places this question in a larger and longer stream of thought and will recall for students of history Friedrich Nietzsche’s 1874 essay on “On the Use and Abuse of History for Life,” an evergreen source of reflection on this subject. It is a real question, as Nietzsche argued, whether historical knowledge is an enhancement for life or an encumbrance, a dead weight on the soul and the spirit that only serves to inhibit the adventurous energies of—dare we say it?—a fully flourishing individual. Nietzsche began his essay with a quotation from Goethe—the great chronicler of the deeds of that scholarship-bowed figure Faust—that “I hate everything that merely instructs me without increasing or directly quickening my activity.”

That states the problem at hand well. And indeed, there is a tendency in modern thought to regard history in even more sinister terms, as a delusion or fantasy, or worse. Remember Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus: “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.” Or Marx in his Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon: “The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

And the question can be taken even deeper than that. Is it really true, what Socrates said about the examined life being the only life worth living? What if what we find out in our examination of the past is something terrible or embarrassing or morally compromising? Is it really better to remember such things? Or is it sometimes better for the health of the soul for us to cultivate the capacity to forget and not inquire too much into a past that may be more of a drag on us than a source of vitality? Nietzsche argues for the latter, and McMahon partly agrees with him, that Nietzsche’s admonition against too much remembering is an “uncomfortable insight” into the reality of the human condition. Many psychologists have come to believe that the Freudian dictum that we need to “work through” the traumatic past may in fact be false, that “letting go” is a better strategy.

And yet, it is surely a part of historical inquiry to give voice and visibility to those people and things that have been silent or invisible, to expand the scope of our understanding and sympathies, and reckon with past injustices. But the critical disposition that dominates the current practice of history may have gone too far. McMahon mentions Walter Benjamin’s celebrated statement that “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism,” and finds it excessive and unbalanced.

Is it sometimes better for the health of the soul for us to cultivate the capacity to forget and not inquire too much into a past?

So how does one find a balance in these things, a balance between the discipline of critique and the necessary role of celebration and gratitude in a genuinely flourishing human existence? It is to McMahon’s immense credit that he even raises such issues and revitalizes the questions that Nietzsche asked a century and a half ago, which have taken on new relevance in a time when the energies of historical scholarship are so overwhelmingly directed against the “documents of civilization.” Should historians think more about the potential effects of their work on the lives and souls of the general public? That question is not answered here, but it certainly is raised in a way that is hard to ignore.

As in any collection of essays, the contents of History and Human Flourishing vary in quality and relevance, and some show the force-fed quality alluded to above, or read like scholarship composed for other occasions and repurposed for this volume. But most of them rise to the level of McMahon’s initial reflections. For example, D. Graham Burnett’s essay on history as a vocation, as a calling, evokes questions similar to Nietzsche’s, even if it arrives, boldly, at the notion that history ought to point us toward “what is eternal,” precisely by contrasting the things that are ephemeral to those that endure. Peter Stearns, who has for many years been pioneering the historical study of emotions, recommends a grand tour of various forms of happiness over the course of human history, which it is hoped might uncover insights into what is enduringly important and what we stand in need of today.

There are several essays (including McMahon’s own contribution) dealing with the ways history is a consolation for the disappointments and uncertainties of life as it is actually lived by us. This seems to me a good and sober way of thinking about what the study of history, and the possession of historical consciousness—which are two very different things—might do for us. I would especially have liked to have seen more attention paid in the book to how historical consciousness, both on the individual and the societal level, contributes to human flourishing. In general, the essays in the book are academic works composed by academic writers for academic audiences. And historical consciousness—by which I mean an awareness and appreciation of the past’s immanence in the present—is a subject that academic works of history rarely if ever touch on. That this book does touch on it, in places, and ventures into territory where academics rarely tread is reason enough to be grateful for it, and for the project that gave it life.