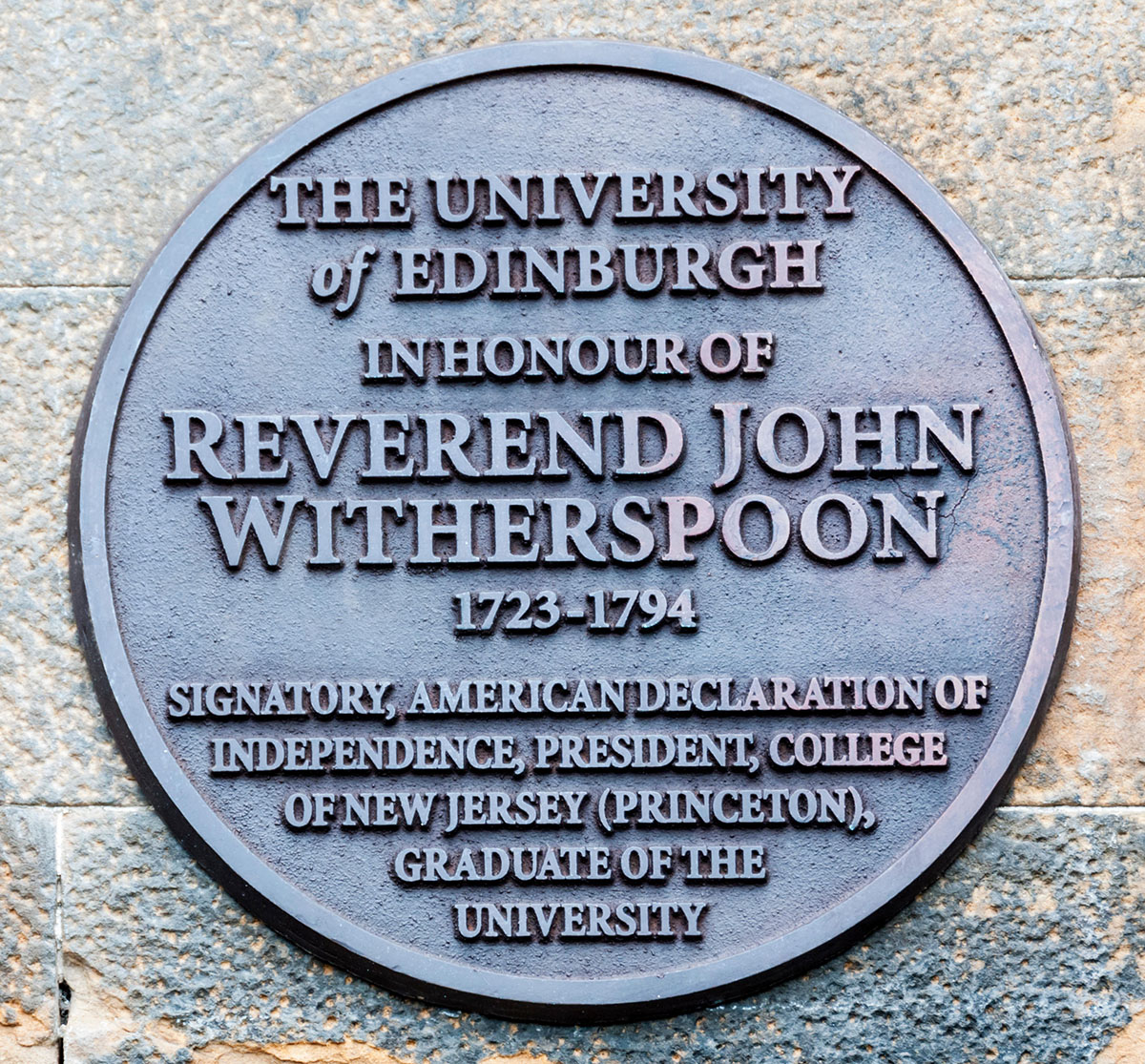

On the campus of Princeton University, near the chapel and the Firestone Library, there is a statue of the college’s president during the American Revolution, John Witherspoon. Outside a few corners of academia, Witherspoon is little remembered anymore. Few Americans know that he was the only clergyman to sign the Declaration of Independence. Even among scholars, he has largely fallen into the faceless category of “Forgotten Founders” of our republic. Far better known, in 2023, is the actress Reese Witherspoon, who claims to be his descendant.

If the American Revolution could be justly called a “Presbyterian rebellion,” one Presbyterian minister in particular was its general. His influence on the founding, and the education, of this nation has remained underappreciated for too long.

Yet in his lifetime, and for at least a century thereafter, Witherspoon was widely esteemed as (in one writer’s words) “one of the great men of the age and the world.” More recently, a small but growing number of historians has concluded that he was probably “the most influential teacher in the entire history of American higher education” and the most important college president America has ever known. It seems not too much to say that, were it not for Witherspoon, American politics in the 1770s and 1780s might have taken a different trajectory.

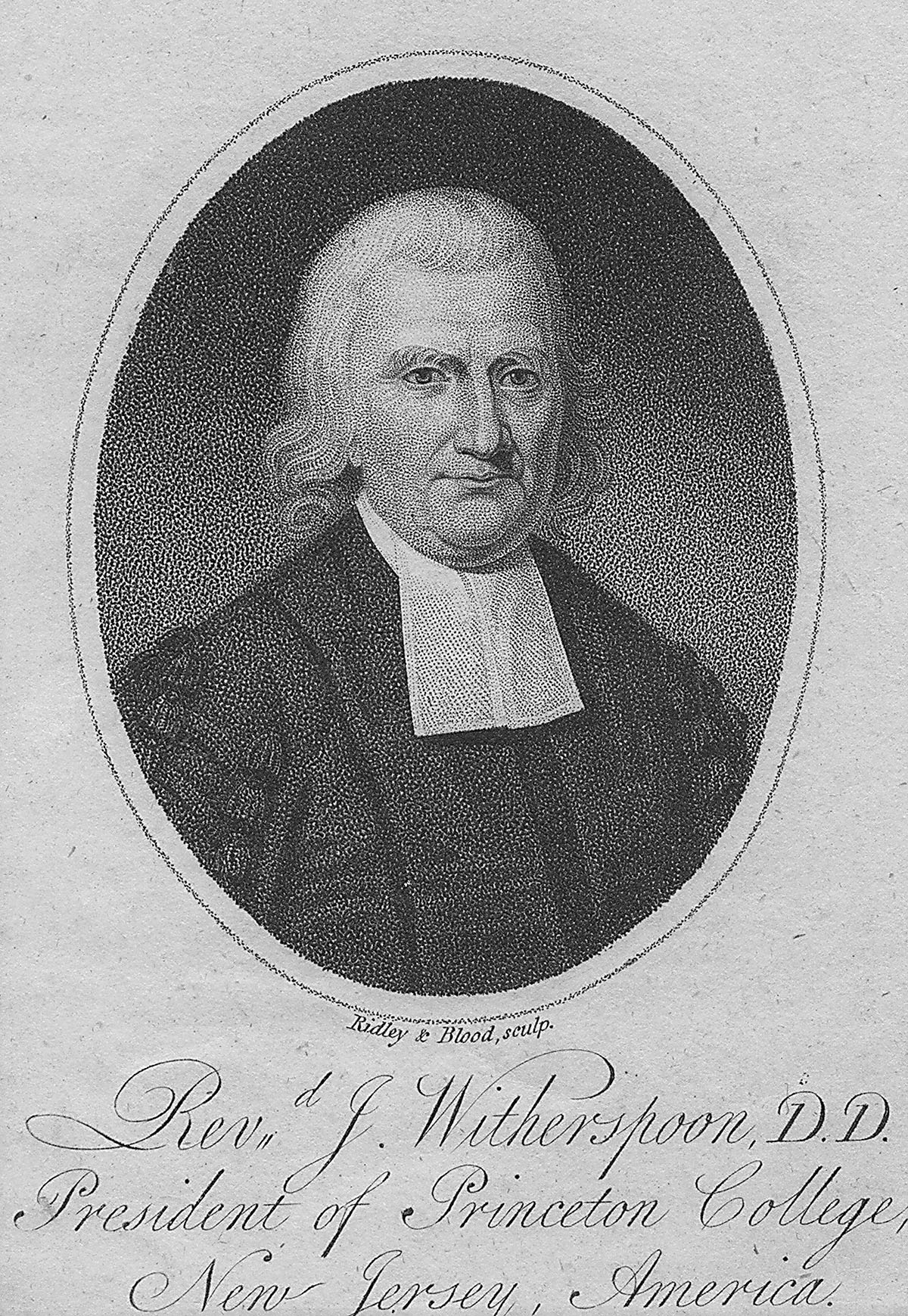

In this essay I wish briefly to explore Witherspoon’s impact on America’s founding generation and the cause for which they fought. He was born in Scotland in 1723, educated at the University of Edinburgh, and ordained into the Presbyterian ministry a few years later. From his early 20s until his mid-40s, he served with increasing distinction as a minister in the Church of Scotland.

During these two decades, Scottish Presbyterians were divided into two contentious factions: urbane and theologically liberal Moderates on the one side, and strict Calvinists, known as the Popular party, on the other. In the protracted contest for control of the national church, Witherspoon became a leader of the Popular party. In 1753 he anonymously published a mordant satire of his opponents in a tract entitled Ecclesiastical Characteristics. Although Witherspoon and his allies eventually lost their battle with the Moderates, his bestselling Ecclesiastical Characteristicsand subsequent writings solidified his reputation as a champion of Christian orthodoxy and brought him to the notice of Presbyterians in the American colonies.

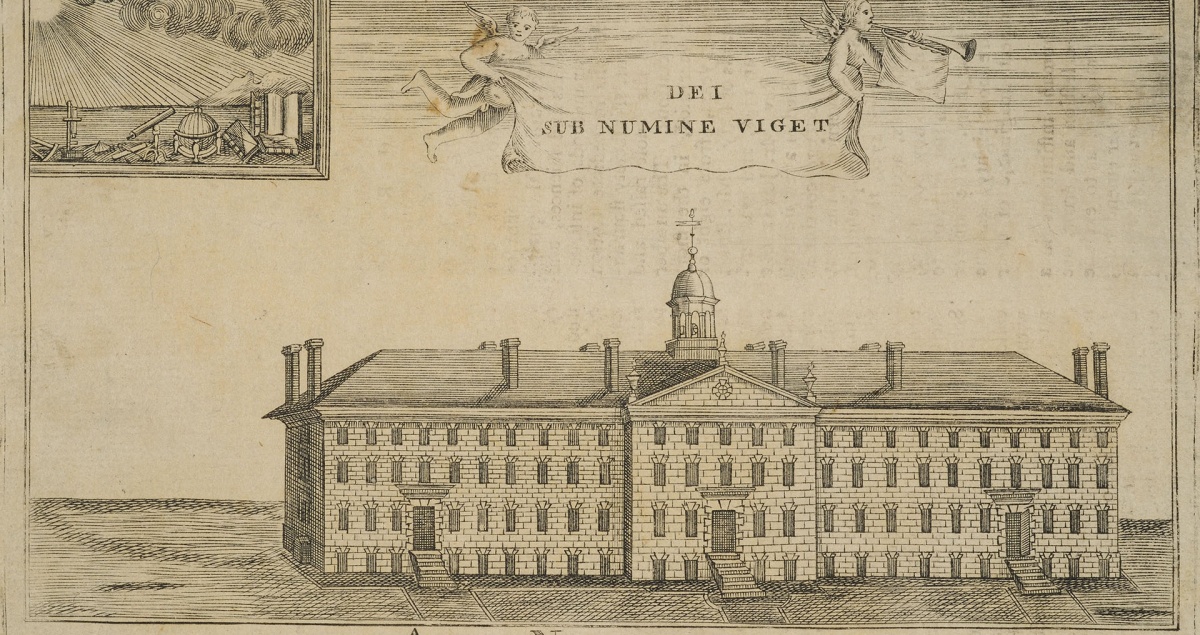

Thus it came to pass that in 1766 the trustees of the little College of New Jersey invited him to become its next president. The college had been founded in 1746 by evangelical, New Side Presbyterians during the ecclesiastical strife unleashed by the Great Awakening. Although the school was officially nondenominational, most of its trustees were Presbyterian. Anxious now to keep their struggling citadel of orthodoxy afloat, and to fend off machinations by anti-evangelical, Old Side Presbyterians to capture it, the trustees turned to Scotland and to Witherspoon. Not only was he an uncompromising Calvinist, a masterful sermonizer, and a learned graduate of the prestigious University of Edinburgh, as an outsider to ecclesiastical politics in the colonies, he also might be able to overcome the residual rivalry between New Side and Old Side Presbyterians and steer the church in America in a healthier direction.

At first Witherspoon declined, in the face of his wife’s impassioned objections. But eventually she relented, and in August 1768 the Scottish divine and his family arrived in America, where they were welcomed with hospitality bordering on rapture. Witherspoon’s new surroundings must at first have given him a dose of culture shock. The town of Princeton contained perhaps 50 dwellings—a far cry from the thriving city in Scotland he had just left behind. As for the vaunted College of New Jersey, except for the new president’s home (which was still being built), its campus consisted of exactly one building: a three-story, stone structure known as Nassau Hall, which served as a combination dormitory, classroom building, and chapel. The teaching staff consisted of the president, one professor, and two or three tutors. The student body comprised fewer than 100 teenage boys.

But there was much about the school that he undoubtedly found familiar and satisfying: its rigorously classical curriculum, for example. Like other colonial colleges in those days, much of Princeton’s curriculum, especially in the freshmen and sophomore years, centered on the intensive study of ancient Greek and Latin literature in the original languages. An accomplished Latinist himself, Witherspoon corresponded with one of his sons in Latin, and when he built a country home a mile north of town a few years later, he named it “Tusculum,” after the town in ancient Italy where Cicero had his villa.

Nor did the new president seem fazed by the highly regimented work environment that he would now oversee. In 1770, early in his tenure, a typical day on campus ran thus: At 5:00 in the morning, students were awakened by a bell and given half an hour to dress. At 5:30 they assembled for compulsory morning prayers, after which they studied until breakfast at 8. After breakfast, they were free until 9, when they went off to “recitation” (class) for four hours. After dinner, which was served at 1 p.m., they were on their own until study time between 3 and 5 in the afternoon. At 5 o’clock, a bell summoned them to evening prayers, followed by supper at 7. At 9 p.m., another bell signaled that they must return to their rooms for study and sleep. On Sundays they were required to attend two services: one at 11 a.m. in the local Presbyterian church, the other at 3 p.m. in Nassau Hall. Dr. Witherspoon, of course, delivered the sermons in both places.

A Felt Presence

The new college president wasted no time in doing what college administrators, even then, had to do: raise money and advertise. Before long he had stabilized his institution’s rickety finances and augmented its library. Between 1768 and 1770 he undertook successful fundraising trips in New England and the South, where he preached sermons, met leading men of affairs, and fortified his connections with fellow Presbyterians, who began to look to him as their leader. His lengthy travels gave him a capacious sense of America that relatively few of the native-born yet possessed.

But Witherspoon had not come all the way from Europe to be a mere administrator. The heavy-set minister was a man of force and strong convictions. In the pulpit he delivered his elaborate sermons entirely from memory, without a note in front of him—an attribute that hugely impressed his listeners. Never flamboyant in his public addresses, he exuded what we today would call gravitas. One of his students later wrote that Witherspoon had “more of the quality called presence” than anyone the student ever met except for George Washington. On campus, Witherspoon soon made his presence felt.

Here we come to the first way in which Princeton’s new pedagogue helped to shape America’s founding generation. Although in Scotland he had made himself notorious by lampooning the worldliness, smugness, and theological laxity of the Moderates in the Scottish national church, on a deeper intellectual level he was closer to them than it seemed. Like many of them, he had been profoundly touched by the 18th-century intellectual cloudburst known as the Scottish Enlightenment. And it was the Scottish variant of the Enlightenment that this Calvinist pastor now imported into Princeton, from which, via his students, it shortly entered the mainstream of American thought.

When Witherspoon arrived in 1768, Princeton’s intellectual atmosphere still bore some of the marks of its revivalistic origins. The college’s tutors were ardent partisans of the philosophical idealism associated with Bishop George Berkeley in England and Jonathan Edwards in America. To the tutors’ dismay, the new president vehemently rejected Berkeleyan idealism, or “immaterialism” as he insisted on calling it. He soon instructed his students:

The truth is, the immaterial system is a wild and ridiculous attempt to unsettle the principles of common sense by metaphysical reasoning, which can hardly produce any thing but contempt in the generality of persons who hear it, and which I verily believe, never produced conviction even in the persons who pretend to espouse it.

Within a year the disappointed tutors had left the college, and Witherspoon had added the professorship of divinity to his duties.

The immigrant Scots preacher was a man with his feet on the ground, and the ground to him was real.

Far from being a fervent, New Side revivalist, Witherspoon turned out to be a vigorous adherent of what we now call Scottish realism—and a tenacious foe of abstract metaphysical speculation of all kinds. The immigrant Scots preacher was a man with his feet on the ground, and the ground to him was real. Disdaining both the turgidity of Berkeleyan idealism and the radical epistemological skepticism of David Hume, he stoutly defended a philosophy of what he called “plain common sense.” In Witherspoon’s world there was no irreconcilable conflict between reason and biblical revelation. “If the Scripture is true,” he told his students, “the discoveries of reason cannot be contrary to it; and therefore, it has nothing to fear from that quarter.” Significantly, his inaugural address as president was entitled On the Unity of Piety and Science.

Historians agree that Witherspoon was the principal conduit of Scottish common sense realism into American intellectual life. As one scholar has written, he “brought the Enlightenment from Scotland to the College of New Jersey and gave it an evangelical baptism.” Thanks to Witherspoon and his disciples, Scottish “moral sense” and “common sense” philosophy came to dominate the American academic landscape for the next one hundred years.

More importantly for our purposes, Witherspoon’s worldview and no-nonsense temperament meshed easily with the pragmatic and experimental cast of American thought at the time of the nation’s founding and beyond. Moreover, his teaching carried profoundly democratic and very timely political implications. If all people (as Witherspoon taught) are endowed with an innate moral sense (called “conscience”) as well as common sense which permits us to apprehend self-evident truths, what did this tell us about the capacity of all people for self-government? When combined with Witherspoon’s unshakable Calvinism, with its insistence on men’s imperfection and depravity, his middle-of-the-road philosophy acted both as a stimulus to political betterment and as a brake on the utopian impulses and faith in human self-sufficiency latent in the Enlightenment project. Good Calvinist that he was, Witherspoon recognized that (as Mark Twain later wrote) “there is a little bit of human nature in all of us.” In other words, man’s capacity for reason does not make man perfect or perfectible. By stressing both a “common sense,” realist philosophy and humanity’s innate propensity to sin, Witherspoon helped to make the American Enlightenment a comparatively pragmatic, nonideological phenomenon. It is not far-fetched, for instance, to discern echoes of Witherspoon in his student James Madison’s hardheaded ruminations about human nature in the Federalist Papers.

“School for Sedition”

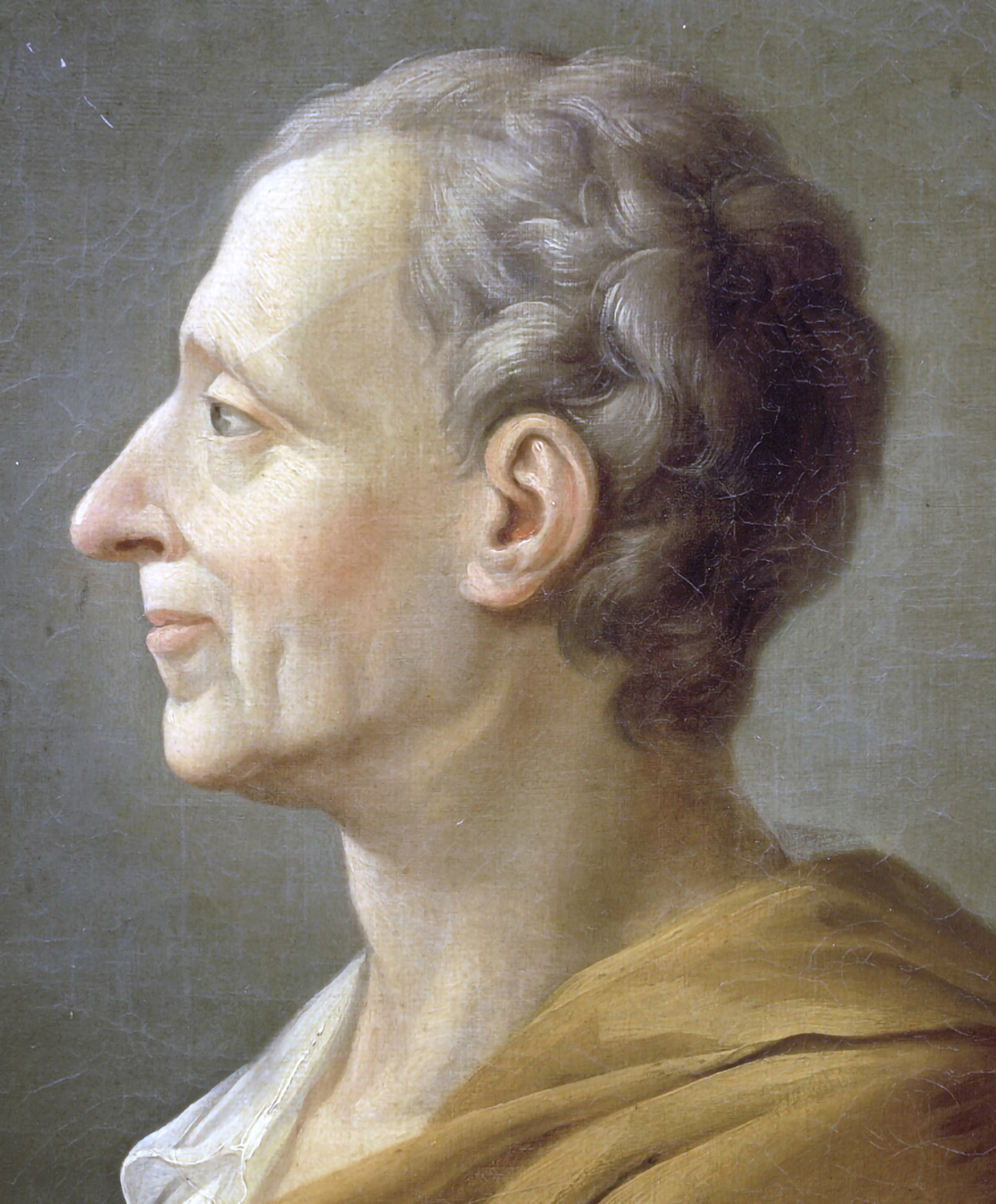

The primary vehicle for Witherspoon’s eclectic teaching was his required senior year course in moral philosophy: an amalgam of ethics, political philosophy, and jurisprudence. Witherspoon used no textbook. Instead, he wrote out an extensive set of lecture notes, which each student was then obliged to copy in toto. It was only after Witherspoon’s death that his lecture notes were published. Long before then, handwritten copies circulated far beyond the College of New Jersey, as his former students—and students of students—disseminated his teachings throughout the nation. By these lectures the president introduced a generation of young Princetonians to the works of John Locke, Francis Hutcheson, and Montesquieu, among others. Heavy on Whig political theory and 17th-century republican theory, the lectures helped to mold his students’ political identity and provide them with the conceptual tools and vocabulary for political discourse—discourse that eventuated in resistance to the British monarchy and the founding of the American republic.

Princeton was becoming known as well as a ‘school for statesmen’—or, as its detractors thought, a ‘seminary of sedition.’

Witherspoon soon put his stamp on the college’s curriculum in other ways. Keenly interested in the sciences (although no scientist himself), in 1771 he appointed the college’s first professor of mathematics and natural philosophy (science). Thus the study of the world was placed on a par with the study of divinity. By 1772, Witherspoon himself was teaching not only divinity and moral philosophy but chronology, history, and rhetoric as well. When published after his death, his Lectures on Eloquence had the distinction of becoming, according to most students of the subject, the first American treatise on rhetoric.

The arts of rhetoric, in fact, seemed to fascinate the new college president. In 1771 he inaugurated the practice of holding speaking contests in English, Latin, and Greek on the day before Commencement. Any student in the college could compete for the prizes. Many of the speeches focused on current political controversies. He expanded the college’s tradition of having freshmen, sophomores, and juniors recite orations every night on a special stage in Nassau Hall after evening prayers. Formerly, two students had been called upon to perform each evening; Witherspoon increased the quota to three. Seniors were permitted to declaim just once every five or six weeks, but they were obliged to compose their own orations and to deliver them in front of invited guests. As if all this supervised speechmaking were not enough, in 1769 and 1770 (with Witherspoon’s apparent blessing) the undergraduates themselves organized the American Whig and Cliosophic societies, which engaged in spirited, literary “paper wars” against each other. In all these ways, the indefatigable Witherspoon prepared his young charges for lives of service on a larger stage.

Increasingly, it was that larger stage—the turbulent world of imperial and colonial politics—that impinged on the consciousness of his academic village. Witherspoon arrived in the New World at a time of growing turmoil brought on by the British government’s attempts to tax its North American colonies. Although Witherspoon did not immediately enter the controversy, it was not hard to infer where his sympathies lay. At the Commencement ceremonies in 1769, the College of New Jersey ostentatiously awarded honorary degrees to John Dickinson, author of the patriotic Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, and to John Hancock, whose sloop Liberty the British had recently seized for supposedly failing to pay import duties on all its cargo. At the Commencement exercises in 1770, Witherspoon’s son James, a graduating senior, delivered an oration in Latin asserting the duty of subjects of a king to resist him if he acted tyrannically. At Commencement in 1771, the seniors Hugh Breckenridge and Philip Freneau (who went on to later literary fame) presented a rousing, original patriotic poem entitled “The Rising Glory of America” to thunderous applause.

Occasionally, the displays of Whiggish sentiment took more dramatic form. Early in 1774, shortly after the Boston Tea Party, the students at Princeton staged a “tea party” of their own. They seized the college steward’s winter store of tea, and, as the campus bell tolled, burned the tea in a bonfire, along with an effigy of Massachusetts’ royal governor, Thomas Hutchinson, with a canister of tea strung around his neck. President Witherspoon did not interfere. Some weeks later, a group of his students organized their own militia company, complete with uniforms. Again the president made no known effort to stop them.

All this patriotic ferment underscored a subtle but deepening trend at the college in the 1770s and beyond. Although still an institution where more than 40% of the students were called to the Protestant ministry, it was becoming known as well as a “school for statesmen”—or, as its detractors thought, a “seminary of sedition.” Witherspoon’s reorientation of the curriculum and his emphasis on rigorous training in public speaking encouraged this secularizing process.

All this might not have mattered too much except for one fact: in the early 1770s, there were only nine colleges in the British colonies on the Atlantic seaboard. Between 1769 and 1775, just 830 young men took their B.A. degrees from these institutions. Of them, 150 (nearly 20%) came from the College of New Jersey. Strategically located between New York and Philadelphia, and drawing its clientele increasingly from the South (where there were no colleges, except for William and Mary), by 1775 Witherspoon’s school had a more geographically diverse enrollment than any of its competitors. By this measure, it was the least parochial and most national of America’s educational institutions.

It was also the educational capital of American Presbyterianism, a rapidly growing segment of the religious population. By 1775 there were nearly 600 Presbyterian churches in the 13 colonies, and immigration from Presbyterian Scotland and Northern Ireland was surging, at the rate of 10,000 new settlers per year. As the most prominent Presbyterian clergyman in the American colonies, Witherspoon knew that when he spoke, more likely than not his religious brethren would listen.

An Imprimatur for War

So far Witherspoon had spoken very little—at least publicly—about the quarrel between the colonies and the mother country. By 1774 his reticence had receded. Meeting Witherspoon for the first time that summer, John Adams found him “as high a Son of Liberty as any Man in America.” Once upon a time, back at his parish in Scotland, Witherspoon had preached that it was a sin for a minister “to desire or claim the direction of such matters as fall within the province of the civil magistrates.” But in the wake of the Boston Tea Party and the British reprisals known as the Coercive Acts, he changed his mind.

Here we come to the second great contribution that Witherspoon made to the forging of an American identity in the founding era: his labors as a public intellectual and activist in support of the American cause. On July 4, 1774, he took his first overt step into the arena by accepting membership on the committee of correspondence for Somerset County. A little over two weeks later, he joined his fellow committeemen at a provincial congress that elected New Jersey’s delegates to the First Continental Congress. The following December, he was reelected to his county’s committee of correspondence and endorsed the resolves recently adopted by the Congress in Philadelphia. A few months later, in May 1775, at the annual meeting of the Presbyterian Synod of Philadelphia and New York, just weeks after the battles of Lexington and Concord, he chaired the committee that drafted a powerful pastoral letter that was read in Presbyterian pulpits throughout the region. While moderate in tone and respectful of King George III, the document nevertheless described Britain’s recent actions as “unmerited oppression” and called upon American Presbyterians to “adhere firmly” to the resolutions of the Continental Congress. Bit by bit, with Witherspoon in the vanguard, colonial Presbyterians were inching toward a break with the British Empire.

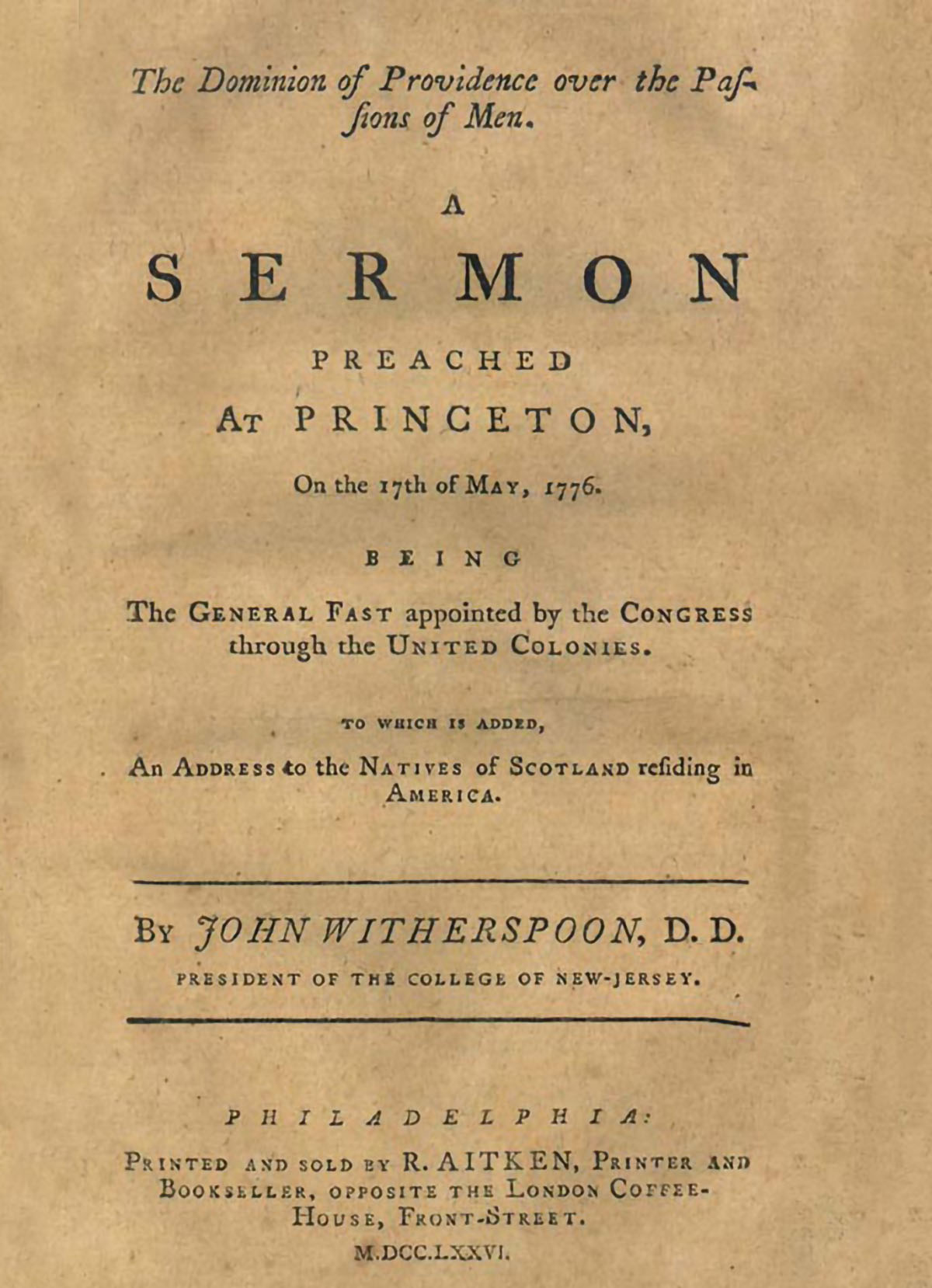

By the spring of 1776 Witherspoon was an outspoken advocate of American independence. This became apparent to all on May 17, when he delivered at Princeton what was probably the most consequential sermon of his life. In it he solemnly asserted that separation from Britain and resistance to its authority were now justified.

You are all my witnesses [he declared] that this is the first time of my introducing any political subject into the pulpit. At this season, however, it is not only lawful but justified, and I willingly embrace the opportunity of delivering my opinion without any hesitation, that the cause in which America is now in arms, is the cause of justice, of liberty, and of human nature. … There is not a single instance in history in which civil liberty was lost, and religious liberty preserved entire. If therefore, we yield up our temporal property, we at the same time deliver the conscience into bondage.

Witherspoon’s sensational sermon was quickly published. Although its precise impact is difficult to measure, its import was plain: the most distinguished Presbyterian and Scottish immigrant in North America had just given his imprimatur to the war for independence.

A few weeks later, after Witherspoon participated in deposing New Jersey’s royalist governor, New Jersey’s provincial congress elected Witherspoon to its delegation to the Second Continental Congress, meeting in nearby Philadelphia. The delegates arrived at the end of June, just as Congress was deliberating whether to adopt a resolution for independence. Even now, some members hesitated to take the final step. But not Witherspoon. When one of the members (possibly John Dickinson) objected that the country was “not yet ripe for so important and decisive a measure,” Witherspoon replied that in his judgment “it was not only ripe for the measure but in danger of becoming rotten for the want of it.”

We shall probably never know whether Witherspoon’s tart rejoinder tipped the scales. But within hours of his speech, Congress voted on July 2 for independence and, on July 4, for the Declaration of Independence that he signed.

‘There is not a single instance in history in which civil liberty was lost, and religious liberty preserved entire.’

For the Presbyterian minister, clad always in clerical garb, this was not the end, but merely the end of the beginning, of his political career. For six of the next seven years, while still serving as his college’s president and pastor of a church in Princeton, he was a leading member of the Continental Congress, where he represented New Jersey and served on 126 committees (more, it appears, than anyone else), including the Board of War.

If his colleagues manifestly respected his intellect and character, so, too, in their own way, did the British. In the summer of 1776, British troops on Long Island burned him in effigy. A New Jersey Loyalist and Anglican minister named Jonathan Odell publicly excoriated him in a poem as “Witherspoon the great”:

I’ve known him to seek the dungeon dark as night

Imprison’d Tories to convert or fight,

Whilst to myself I’ve hummed in dismal tune

I’d rather be a dog than Witherspoon.

Across the ocean, King George and others referred to the war as a “Presbyterian rebellion”; it is likely that they had a certain renegade Scotsman in mind. The British general Sir Guy Carleton later called Witherspoon a “political firebrand who perhaps had not a less place in the revolution than Washington himself. He poisons the minds of his young students and through them the Continent.”

Ravaged by War

Even after the Revolution was won, Witherspoon did not forsake the public square, where he argued for hard-money economic policies and measures nationalistic in tendency. In 1787, as a delegate to New Jersey’s ratification convention, he voted to ratify the proposed new Constitution devised in part by his onetime student, James Madison. It is a mark of Witherspoon’s stature that, when George Washington rode north to New York City in 1789 to take his oath of office as our first president, he visited Witherspoon in Princeton and may have spent the night at Tusculum.

But if the American Revolution brought Witherspoon new influence, it had not been without cost. In 1777 his eldest son, a major in the American army, died in the battle of Germantown. The College of New Jersey also suffered enormously. In the autumn of 1776, as British soldiers pressed down from the north, Witherspoon closed the college, sent the students home, and fled to safety in Pennsylvania. When the redcoats arrived on December 7, they occupied Nassau Hall and ravaged the community. Three weeks later, after George Washington famously crossed the Delaware, it was the British who were obliged to give ground. At the battle of Princeton, on January 3, 1777, some of the retreating British soldiers smashed the windows of Nassau Hall in order to fire upon the Americans. The Americans proceeded to pound the building with cannon fire. One of the cannon balls evidently sailed through an open window and decapitated the college’s portrait of King George II. Not long after that, the trapped British troops surrendered. (The frame of this portrait, by the way, was later recovered. It now holds a magnificent portrait of “George Washington at the Battle of Princeton” by Charles Willson Peale that Witherspoon helped to commission in 1783. The painting is in the collection of the Princeton University Art Museum today.)

For the next several months, American soldiers occupied the campus, with little more regard for property than the redcoats had shown. Indeed, for the next five years the impoverished college was but a skeleton of its former self, graduating no more than seven students a year. Although the Continental Congress eventually awarded the college nearly $20,000 to repair its badly damaged physical plant, it did so in depreciated paper currency worth only 5% of its face value. (This may help to explain Witherspoon’s attitude toward paper money.) It would be years before Nassau Hall was again fully habitable.

But there were compensations. In mid-1783 the Continental Congress itself, in a state of panic, left Philadelphia and took up residence in Princeton after a mob of mutinous American soldiers in Philadelphia demanded their back pay. From June to the following November, Congress conducted its sessions in Nassau Hall. During these months the town of Princeton and the College of New Jersey were literally the capital of the United States. At the college’s commencement that September, the members of Congress, “as a compliment” to the college and its revered president, attended the ceremonies en masse. Among those present was another visiting dignitary, George Washington.

Prestige and praise, of course, could not pay the bills, and in the ensuing decade Witherspoon struggled mightily to improve his college’s solvency as well as its intellectual luster. It was a daunting task, but he lived to see the institution award 37 B.A. degrees in 1792—the most, to that date, in its history.

A Legacy of Accomplishments

More and more, in his final years, Witherspoon spent time at Tusculum, where he pursued his clerical and political interests and his hobby of what he fondly called “scientific farming.” Here, too, his “common sense” approach to life prevailed: to him, scientific farming primarily meant growing vegetables. One day a visiting lady said to him: “Why Doctor, you have no flowers in your garden!” “No, Madam,” he answered, “no flowers in my garden, nor in my discourses either!”

In 1794 the “old doctor” (as he was called) died at his home at the age of 71. How may we sum up his contributions to America’s founding? First, as I have indicated, he introduced and disseminated the tenets of Scottish common sense philosophy in fertile intellectual soil, helping thereby to shape the contours of the American mind for generations to come. You might say that he gave the Enlightenment in America a Calvinist twist, rendering it more resistant to abstract ideology and utopian illusions than it might otherwise have been. Second, his unflagging intellectual and political activism in the 1770s and 1780s bestowed crucial legitimacy on the cause of American liberty. Without his extraordinary influence among Presbyterians, without his aura of gravitas and his nationalistic sensibility, the baker’s dozen of American colonies might well have stumbled in other directions.

Finally, we cannot fully comprehend Witherspoon’s legacy without mentioning his remarkable success as an educator and mentor. Princeton in his time was a tiny institution by modern standards. At Witherspoon’s death its faculty consisted of just five individuals. During his 26 years as the college’s president, it awarded only 478 bachelor’s degrees, an average of fewer than 20 per year.

But think of what these men accomplished! The graduates of the College of New Jersey during Witherspoon’s tenure included:

12 members of the Continental Congress

5 delegates to the Constitutional Convention

1 president of the United States (James Madison)

1 vice president of the United States

28 U.S. senators

49 members of the U.S. House of Representatives

12 governors

3 Supreme Court justices

Thirteen Princetonians who graduated during Witherspoon’s presidency became college presidents themselves. In fact, more than 10 American colleges and academies were founded by men who took their degrees under Witherspoon. Sir Guy Carleton was right: the “old doctor” had spread his influence through a continent.

As the sestercentennial of our national independence approaches, let us hope that the Reverend John Witherspoon will again be recognized for his extraordinarily consequential devotion to the three lodestars of his life: religious faith, higher education, and American liberty. It was a calling that helped make America what it became.

This essay is adapted from a lecture presented at the ISI Summer Institute in Princeton in June 2011.