This essay is an edited transcript of Bishop Robert Barron’s plenary lecture, delivered at Acton University on June 21, 2023.

It might be argued that the central preoccupation of the cultural conversation in the West today is “wokeism.” This system of thought and action has rather remarkably found its way into practically every nook and cranny of our political, economic, and cultural arenas, and it’s having a massively deleterious effect on our culture. One of our major political parties has largely organized itself around defending woke ideas and implementing woke strategies, and the other major party has begun to organize itself against the same.

The word “woke” is heard a lot these days, but what is it? What are its roots? And what does it mean for politics, religion, and the future of our culture? Bishop Robert Barron provides some much-needed insights.

There is much heat and energy around the conversation, but very often, I have found, people don’t know precisely what they’re talking about when they advocate or attack wokeism. My basic argument is that wokeism is hardly an ephemeral ideology that sprang spontaneously forth in the summer of 2020; rather, it has a long and clearly discernible intellectual pedigree. If we are to stand against it—as I do—we must do so in a sophisticated way, understanding where it came from.

If I might begin with a description more than a definition, I would say that wokeism is a popularization of critical theory. Critical theory, which I will endeavor to describe throughout this talk, is an intellectual movement that flourished in the mid-20th century, largely in the French and German academies. Some of the names associated with it include Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, Jacques Derrida, and Michel Foucault. It made its way, during the 1960s and 1970s, into the American academy. René Girard, though he would have been an opponent of wokeism, was involved in organizing a conference at Johns Hopkins in the late 1960s, when Derrida came over to these shores for the first time. Girard said it was the moment when French structuralism and postmodernism made its way into the American academy. There it gestated for several decades until it sprang forth as a bacillus into the wider bloodstream of the society during that summer of 2020.

In order even adequately to grasp this complex intellectual tradition, we would require at least two or three semester courses, but I will try, in this brief presentation, to draw together five of the strands that make up critical theory, and in doing so persuade you that it functions as the intellectual matrix for wokeism. Then I would like to suggest how Catholic Social Teaching stands dramatically athwart the assumptions behind wokeism. My hope is that this exercise will enable us better to engage, both intellectually and practically, this dangerous movement.

The Radicalization of the Modern Self

The first quality of critical theory is what I will call a radicalization of the modern sense of the self. The two most important players among the modern philosophers are René Descartes and Immanuel Kant, both of whom effect a sort of Copernican revolution in regard to the subject and object. If you want to see the place where modernity was born, you can find it in the German city of Ulm, where Descartes, then serving as a soldier in the Bavarian army, retreated to a heated room in a search for the foundations of philosophy. There he came up with the famous Cogito ergo sum—“I think, therefore I am.” I can doubt tradition, religion, and even sense experience, but the one thing I cannot doubt is that I’m doubting.

Notice that Descartes recommends that the whole of objectivity be brought before the bar of subjectivity for adjudication, since the one absolutely certain truth is the cogito. On this basis, he made a sharp demarcation between what he called res extensae and res cogitantes—that is to say, “extended things” out in the world and “thinking things” on the inside. The radical division between body and soul is bequeathed to modernity as a typical anthropology.

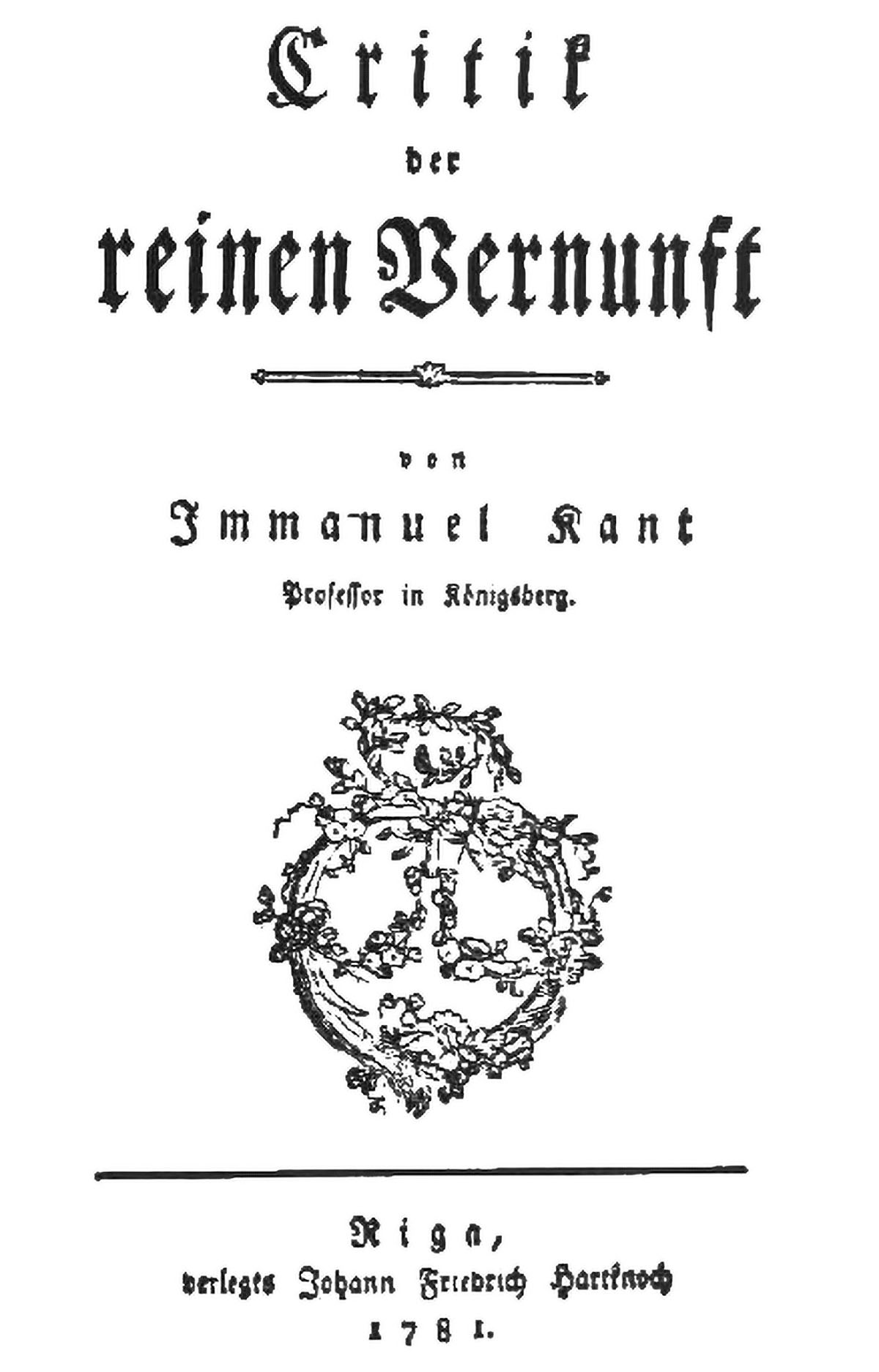

Kant, the second figure, famously argues in his Critique of Pure Reason that the great organizing categories of traditional philosophy—time, space, causality, identity, etc.—are not actually in the world but rather in the mind as a priori structures. Therefore, the mind does not revolve around reality; rather, reality, as it were, revolves around the mind.

We find something very similar in Kant’s account of the moral life. The only thing that can be called good in an unrestricted sense, he says, is a good will. Kant privileges the interior over the exterior: I do not look to my acts in the world to determine what is right or wrong; rather, it is the will, governed by the categorical imperative discovered at the root of its own existence, that determines moral rectitude or turpitude.

Now, these philosophical moves in both Descartes and Kant, which place the real self in the deep, hidden center of one’s identity, over and against the body, have their roots in ancient gnosticism, which in a very similar way privileged the inside over the outside. Read Cyril O’Regan on this point. But the postmoderns and critical theorists, I would argue, radicalize this modern sense of the self effected by Descartes and Kant, giving the hidden, interior, “true” self complete dominance over the body.

This viewpoint came to perhaps fullest expression in Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialism, which he defined as the primacy of existence over essence. In Sartre’s terms, this means that freedom precedes and determines meaning and purpose. Who I am is a function not of certain objective givens but rather of my sovereign choice.

If you don’t see the influence of this revolution in the rhetoric today regarding gender identity, you are not paying attention. Time and again, we are told that the “real me” can be something other than the body that I carry around, and that the former can exercise a sovereignty over the latter. Though gender fluidity was not a thing in Sartre’s time, it follows neatly from his philosophy of the radicalized modern self, the privileging of the interior over the exterior. And instead of Descartes’ cogito or Kant’s a priori ideas, the postmoderns insist that cultural prejudices, preexisting in our minds, inevitably color our perception of reality.

In Sartre’s terms, who I am is a function not of certain objective givens but rather of my sovereign choice.

Opposing this, of course, is the biblical and classical idea of the true self as a union of body and soul. The insistence of my intellectual hero, St. Thomas Aquinas, that the soul is the “form” of the body is telling in this context, for it assumes that the soul does not have a manipulative sovereignty over the body. It includes the body, animates the body, makes the body what it is. Thomas specifies that the “soul is in the body, not as contained by it, but as containing it.” Therefore, this dichotomization between the “real me” in here and the body out there simply doesn’t work. This terribly erroneous anthropology is now taken for granted, and we have to stand athwart it.

The Relativization of Truth

A second principal mark of postmodernism and critical theory is a profound skepticism in regard to truth claims. An argument against this position goes back to Plato and Augustine: Whenever you take a radically skeptical position, are you also skeptical about your own theorizing? The irony is that those advocating a relativization of truth do indeed think their own theory is true!

In this skepticism, critical theory stands as much against the Enlightenment as it does against classicism. Taking a cue from Nietzsche’s perspectivism, the critical theorists argue that we never get a grasp of the way things are but only of our limited perspective on them. They consistently pull the curtain back on claims to objective truth and see behind them plays of power. If there is only your truth and my truth, then “truth” is in fact a weapon used by powerful people to maintain their privileges.

The inspiration for much of this is in the theorizing of the patron saint of critical theory: Jacques Derrida. His densely complex texts are famously unreadable, but they function as a sort of scripture for postmodernism. Derrida is most famous for what he called the “deconstructionist” approach to the logocentric tradition of classical philosophy in the West. From the time of the ancients, we had a conviction that logos—language, words—could get us into touch with truth, with reality as it is. Think here of Aquinas, who argued for a correspondence of mind to reality mediated by language. Words give us access to the way things are.

Derrida deconstructs that approach, speculating that “Il n’y a pas de hors-texte”: “There is nothing outside the text.” Rather, what you have is an endless play of what he calls différence. Words refer only to other words, and I stay permanently within the context of the text, where meaning is always deferred. Hence his famous play on words: différence, the difference of words, leads to différance, the deferral of meaning. I never know what things really are, and truth is always open-ended. Does this sound familiar? What was once sort of whispered in the recherché heights of the French academy has come now to be the default position of most young people today.

I once heard Derrida at a conference where someone asked him, “How would you define deconstruction?” He answered in his French that deconstruction means “Viens, oui, oui”: “Come, yes, yes.” What he means is the permanent openness to something new, some fresh configuration of meaning. This sounds positive, but the shadow side, of course, is that there is no final truth, no ultimate settling of a question. There is always something new that can come, some new way of configuring a text. Who am I? What is the purpose of my life? What gender am I? “Viens, oui, oui. Think about it in a fresh way. Don’t be tied to old perspectives. Be open.”

In its comically absurd form, this becomes the distinctively woke idea that even math and science are expressions of white supremacy or exclusion of the powerless. Even basic mathematical statements like two plus two is equivalent to four are epistemic oppression. To insist that one follow the scientific method is just a play of power and the imposition of one way of knowing. You can never say that something is true.

An Antagonistic Social Theory

A third quality of critical theory and therefore of wokeism is a fundamentally antagonistic theory of social relations. The critical theorists get this idea from Karl Marx, whose influence can be seen all over critical theory and, at least implicitly, wokeism. Marx takes Hegel’s dialectical understanding of history—thesis and antithesis converge in a synthesis in the ongoing development of Absolute Spirit—and turns it on its head with his dialectical materialism. Marx opined that the social world is divided into oppressors and oppressed. On his reading, this always came down to economic oppressors and oppressed, those who control the means of production and those who are exploited by this control. He also takes from Hegel—and this is very influential in the present-day conversation—the category of the master-slave relationship. Thus, history is the endless antagonistic conflict of warring groups: the domineering and the dominated, the masters and the slaves.

The point of Marxist philosophy is to foment the class struggle that would lead to the overthrow of the system and the liberation of the oppressed. In his theses on Feuerbach, Marx wrote, “Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways. The point is to change it.” This adage was enthusiastically adopted by all of the critical theorists; in fact, it is what makes their theory “critical.” The purpose of their philosophizing is to bring about the Communist revolution by prompting a violent conflict between the slaves and their masters, the haves and the have-nots.

A major development of this doctrine, undertaken by the critical theorists, is that the categories of oppressor and oppressed were expanded beyond the merely economic. They began to see colonial oppression, sexual oppression, racial oppression, gender oppression, etc., and these have been even more enthusiastically expanded by woke activists today. But the same dynamic holds: the binary of master and slave, oppressor and oppressed.

An exceptionally interesting connection in this context is Derrida’s insistence that certain binaries haunt our linguistic system. Our language, he argues, does tend to favor fundamental divisions: male/female, straight/queer, Western/non-Western, civilized/uncivilized, white/black, etc. We tend to generate meaning by playing these binaries off one another; indeed, meaning is often a function of the dominance of one side of the pair over the other. So, “male, straight, civilized, and white” rules over “female, queer, non-Western, and uncivilized.” It is almost like a computer language: on or off, one or zero. Can you see how so much of the woke rhetoric today follows from this? Woke theorists want to privilege the underside of these classic binary oppositions.

And much of the strategy, Marxist in form, remains the same: the encouragement of conflict between the oppressor and the oppressed for the sake of radical social revolution. Everyone in the society has to fall on one side or the other of this divide; there is no third option or blending of the two, and a social theory predicated upon cooperation necessarily serves the interests of the oppressors.

Substructure/Superstructure

Marx is certainly one of the strongest influences on critical theory, and wokeism has often been described as a form of cultural Marxism. We have already seen this in relation to the antagonistic social theory, but I would also draw attention to Marx’s doctrine of substructure and superstructure, which has proven massively influential today. I was especially struck in the summer of 2020 by this, because I heard it all the time in the rhetoric of the woke activists.

Marx was fundamentally reductionist in his thinking. At bottom, all of social life is predicated upon economic struggle. At the heart of every society is the manner in which it organizes its economic life. Hence, the ancient world was a slave economy, the medieval world was a feudal economy, and the modern world is a capitalist economy. This is the core of society, its substructure.

But this single economic form throws up around itself a protective shell, which consists of practically everything else in the society. The sole purpose of this massively complex superstructure is to protect the substructure. Thus, for Marx, the capitalist system protects itself through politics: what politicians are interested in, finally, is defending the substructure. It protects itself through the military: every war that is fought is, fundamentally, an economic struggle. It protects itself through the arts, which are patronized by the wealthy and therefore tend to support the wealth-generating quality of the economy. Most famously for Marx, it protects itself through religion, which is the opium of the masses, drugging us into an insensibility that keeps us from realizing the pain produced by our oppressive economic system. What’s the point of someone like me? Why are priests fostered by a civil society? Because we are the drug dealers; our whole purpose is to calm people down and protect the economic substructure. Politics, the military, the arts, religion—all of it is simply part of the superstructural defense mechanism.

Marx is certainly one of the strongest influences on critical theory, and wokeism has often been described as a form of cultural Marxism.

Critical theory took this on, but they expanded it beyond economic oppression. They commenced to speculate whether race or colonial empire or gender relations stood at the center of civil society, and therefore to wonder how everything else in the culture served to protect that precious substructure. Can you see this practically everywhere in wokeism? Once we see this Marxist framework, we can understand “The 1619 Project,” which is a good example of this quality. The claim being made by its advocates is that something like slavery and the defense of the slave economy stands at the very heart of the American project, and that everything else is subordinated to it. It reads all of society through that very particular lens.

I thought of this often during the terrible summer of 2020, when there were these almost manic attempts to tear down all of the major institutions of our society, from the judicial system to the federal government. Most famously, there was an effort to “defund the police.” This is all part of a Marxist analysis: these things exist simply to protect a form of oppression, and we should get rid of them.

Power as the Supreme Category

Lastly, critical theory, and therefore wokeism, sees power as the supreme category. The theme of power is a fascinating one in the history of philosophy, and the classical theologians speculated quite a bit about God’s power. The Thomist tradition represents the sane idea that God is all-powerful but also simple. God’s power, which is indeed infinite, is therefore not separate from or at odds with his being, his goodness, his justice, and his other perfections. All the divine attributes and qualities are finally one.

This may sound very abstract, but there is a very interesting upshot to this: it prevents God’s power from becoming arbitrary and absolute. Could God, in his infinite power, make it the case that two plus two equals five? If he’s infinitely powerful, why not? Could God, in his infinite power, make adultery a virtue? If he has declared adultery to be bad, couldn’t he declare it to be good instead?

Thomas’ answer is no, because you would drive a wedge thereby between God’s power and God’s manner of being. He strenuously argued that it is no restriction of God’s power to say that he can’t do the impossible, like make two plus two equal to five, because two plus two being equal to four is simply a participation in the truth that God is. It is also no limitation on God’s power to say that he can’t do the immoral, like make adultery a virtue, because that would be at odds with his own goodness. God cannot embrace either falsehood or sin because it would be repugnant to his own manner of being.

But there was an alternative viewpoint in the late medieval and early modern periods, referred to typically as “voluntarism”—from the Latin voluntas, meaning “will”—which put an enormous stress on the primacy of God’s will. The result was that God’s will was effectively divorced from his being, and his potentia absoluta, his absolute power, became the arbitrary determinant of truth and value. Hence, certain acts are morally wrong because God said so, and certain claims are true or false because God so determined. Descartes goes so far as to say that, if God wanted, two plus two might be equal to five. The voluntaristic God, in a departure from Aquinas, has a power that can overrule and redefine reality.

This voluntarism in regard to God in late medieval and early modern philosophy was transposed to the human order during the modern period, where power again becomes hyper-emphasized. One thinks of William of Ockham’s definition of freedom as a sovereign hovering above the yes and the no; of Schopenhauer’s “world as will”; and, most obviously, of Friedrich Nietzsche’s “will to power.” If God is dead, where does the potentia absoluta go? It goes to us. Our will to power, unlimited by any constraint provided by objective value, is analogous to the power of the voluntaristic God. And all of this comes to full expression in Sartre’s existentialism, according to which an individual in his freedom has a godlike mastery over good and evil.

The voluntaristic God thus morphs into the voluntaristic, all-creating, all-defining self: I can decide on the basis of my absolute freedom the nature of reality; don’t tell me what to do, and don’t tell me who I am. Does that sound familiar? In Casey v. Planned Parenthood, the infamous 1992 decision of the United States Supreme Court in an abortion case, the justices said, “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” Is that all? Here again is the transplanting of the potentia absoluta of God now into the potentia absoluta of the self.

Much of this came together in the thought of Michel Foucault, who is, along with Derrida, arguably the most influential of the postmoderns. When I commenced my doctoral studies in Paris in 1989, just five years after Foucault’s death, the philosopher’s owlish face looked out from every bookstore window in the city. He was the dominant philosophical figure; it was simply impossible to avoid him.

At the center of his project was what he called an act of intellectual archeology, digging under the surface of various social practices today to find their often contradictory antecedents. Thus, he looked at questions of madness and sanity, the manner in which we punish criminals, human sexuality—and he found that at different times, these themes were treated very differently indeed. This led him to set aside claims to objective truth and value and to look, as we have seen, for the power relationships that obtained and the strategies of language and coercion employed by powerful people to maintain their power.

When we listen to the wokeist theorists today, the capacity for self-invention is rampant, and games of oppression are everywhere. It is, finally, all about power. It is Michel Foucault for the masses.

Wokeism and Catholic Social Teaching

If I’ve presented even a relatively adequate account of wokeism, I think you can see, clearly enough, that this ideology stands very much athwart Catholic Social Teaching. First, our social teaching would assume that each person is indeed a subject of infinite dignity, but not the creator of value. To say, in line with critical theory, that the sovereign self invents value—this is supremely dangerous talk. Catholic Social Teaching, it seems to me, stands athwart the value-generating self. Instead, the heart of its social theory is love. Each person is called to love, and love, as Thomas Aquinas said, is not a feeling but rather an act of the will: it is to will the good of the other.

Relatedly, Catholic Social Teaching does not hold to the relativization of truth or a Derridean permanent postponement of meaning and knowledge. Rather, it affirms the objectivity of values, both epistemic and moral, which can be known by the inquiring mind. If we are inventing value for ourselves and vaguely tolerating each other, then we cannot truly love each other. Love has to display itself, as it were, against the background of a hierarchy of objective values, and each person must situate himself in relation to that hierarchy. Otherwise, without a keen sense of the objective good, I don’t know what to will for you.

Thirdly, Catholic Social Teaching does not advocate an antagonistic understanding of social reality in the Marxist manner. Rather, it posits a cooperative view according to which classes and individuals and institutions subsist coinherently and in a mutually corrective manner. Individuals, social classes, and owners and workers all cooperate with one another. Seeing society in antagonistic terms and fomenting violence has no place in Catholic Social Teaching.

Fourthly, Catholic Social Teaching does not resolve the dilemma of the one and the many in the Marxist manner, holding to a substructure-superstructure framework. This reading of society is hopelessly simplistic and dangerous, reducing everything other than the substructure to a problem to be unmasked or undone. Rather, Catholic Social Teaching sees society as a complex web of individuals and institutions subsisting in mutuality. It doesn’t all come down to economics or politics or culture; rather, all of these coinhere. In fact, whenever you say, “It all comes down to [fill in the blank],” you are wrong. Society is complex, and beautiful for that very reason.

Finally, Catholic Social Teaching decidedly does not hold to the primacy of power as the supreme value in the quasi-voluntarist way. Rather, it sees justice and love—which is to say, rendering to each his due and willing the good of the other—as supreme. They are both values in se, valuable in themselves. Could you ever imagine it would be right to do something unjust? Would it ever be right not to be loving? No, of course not, because justice and love are absolute values. The language that Catholic Social Teaching tends to use to express both of these ideas is subsidiarity and solidarity. Power is a dynamic, obviously, within any sort of social arrangement, but it is subordinated to the moral values that it serves.

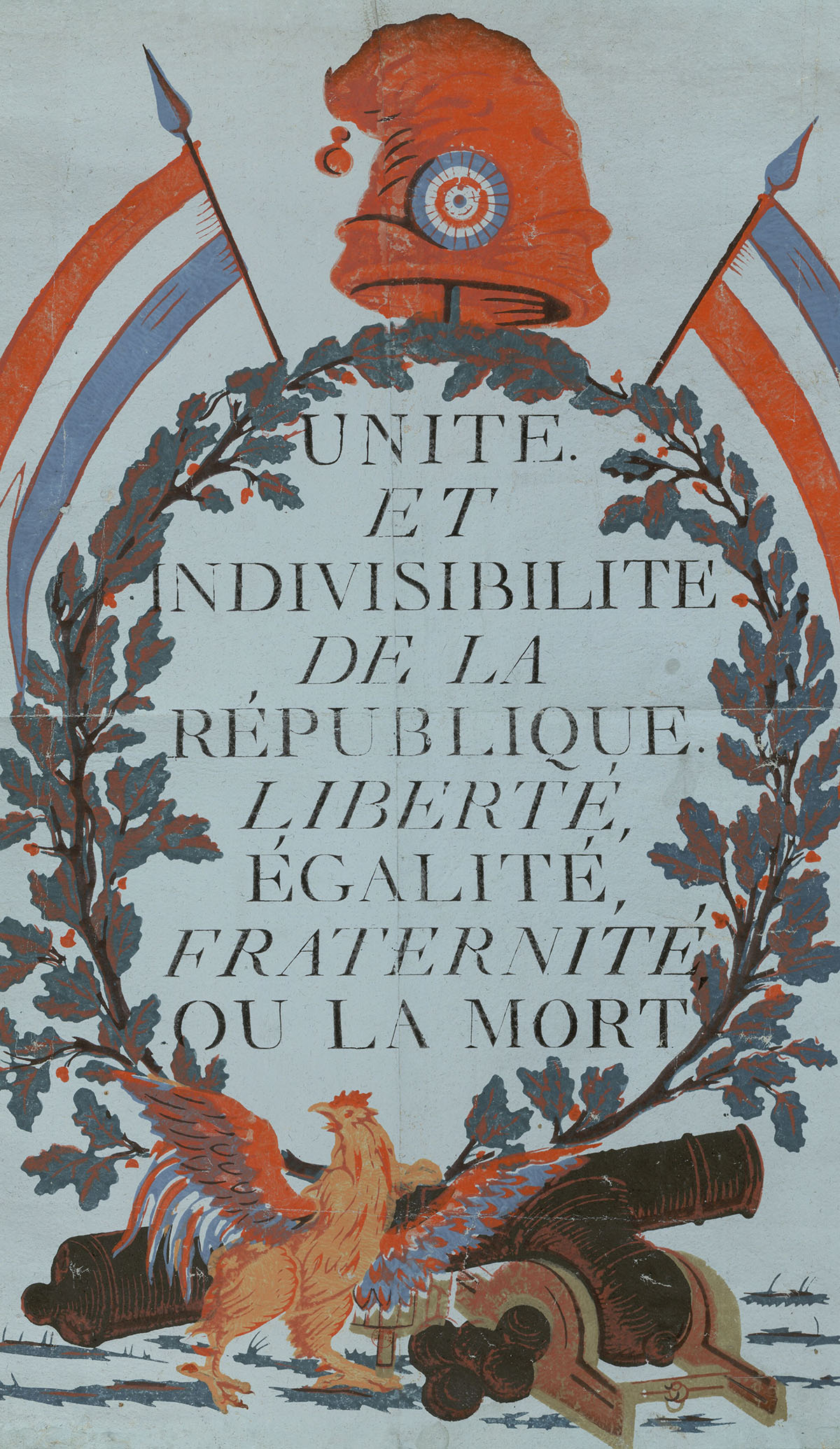

But the values often held to be absolute today—like diversity, equity, and inclusion—are values secundum quid, as the medievals would say. They’re values depending on circumstances, values as far as they go. They are not absolute. However “inclusive” a university may be, for example, students are excluded from the admissions process to be included in that community. The point is that inclusivity is a good thing secundum quid—and the same is true of equity and diversity. These three values are like the triplet that came out of the French Revolution: liberté, égalité, fraternité. Those, too, were values secundum quid. When you try to make secondary values primary values, you lead your nation by a short route to chaos.

If we want to engage wokeism in an intellectually serious way—and, mind you, the theorists of the movement do not want you to do that, but rather want to keep the discussion on emotional grounds—it’s important for us to understand not only where it came from, but also how strongly Catholic Social Teaching stands athwart it.