According to Ron Swanson, the gruff libertarian of the TV show Parks and Recreation, “History began on July 4, 1776. Everything else was a mistake.” Andrew Wilson partially agrees, although he focuses on the year rather than the day: “The big idea of this book is that 1776, more than any other year in the last millennium, is the year that made us who we are.”Remaking the World: How 1776 Created the Post-Christian West is a sweeping book with a strong thesis. It is also a delightful work full of interesting stories and facts.

The late 18th century did more than transform the colonies into America. It saw an explosion of revolutions—political, cultural, economic, scientific—that remade the West forever. The question is why—and why the West?

By Andrew Wilson

(Crossway, 2023)

Wilson contends that Western society is distinctive because of seven transformations: “Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic, Ex-Christian, and Romantic,” which he refers to by the anacronym WEIRDER. Each of these occurred in 1776. He provides a nice overview of this argument in this second chapter, and subsequent chapters unpack and explore each transformation.

The first substantive chapter raises the fraught question of why some peoples developed faster than others. He begins to answer it by considering the earliest human civilizations. Drawing from Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel, he contends that humans shifted from being hunter-gathers to forming civilizations in places with moderate climates and good soil where crops could be cultivated and stored. Those civilizations in the Fertile Crescent were particularly blessed as they had access to large animals that could be domesticated and could travel easily from east to west (which facilitated the spread of knowledge and facilitated trade).

Civilizations arose around the globe, and by 1776 there were 10 major powers in Eurasia: Tokugawa Japan, Qing China, Mughal India, Ottoman Turkey, Romanov Russia, and the Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, French, and British Empires. Several non-European civilizations had been more advanced or richer than any European nation, and yet in the late 18th century the western European powers began to develop far more rapidly than the others.

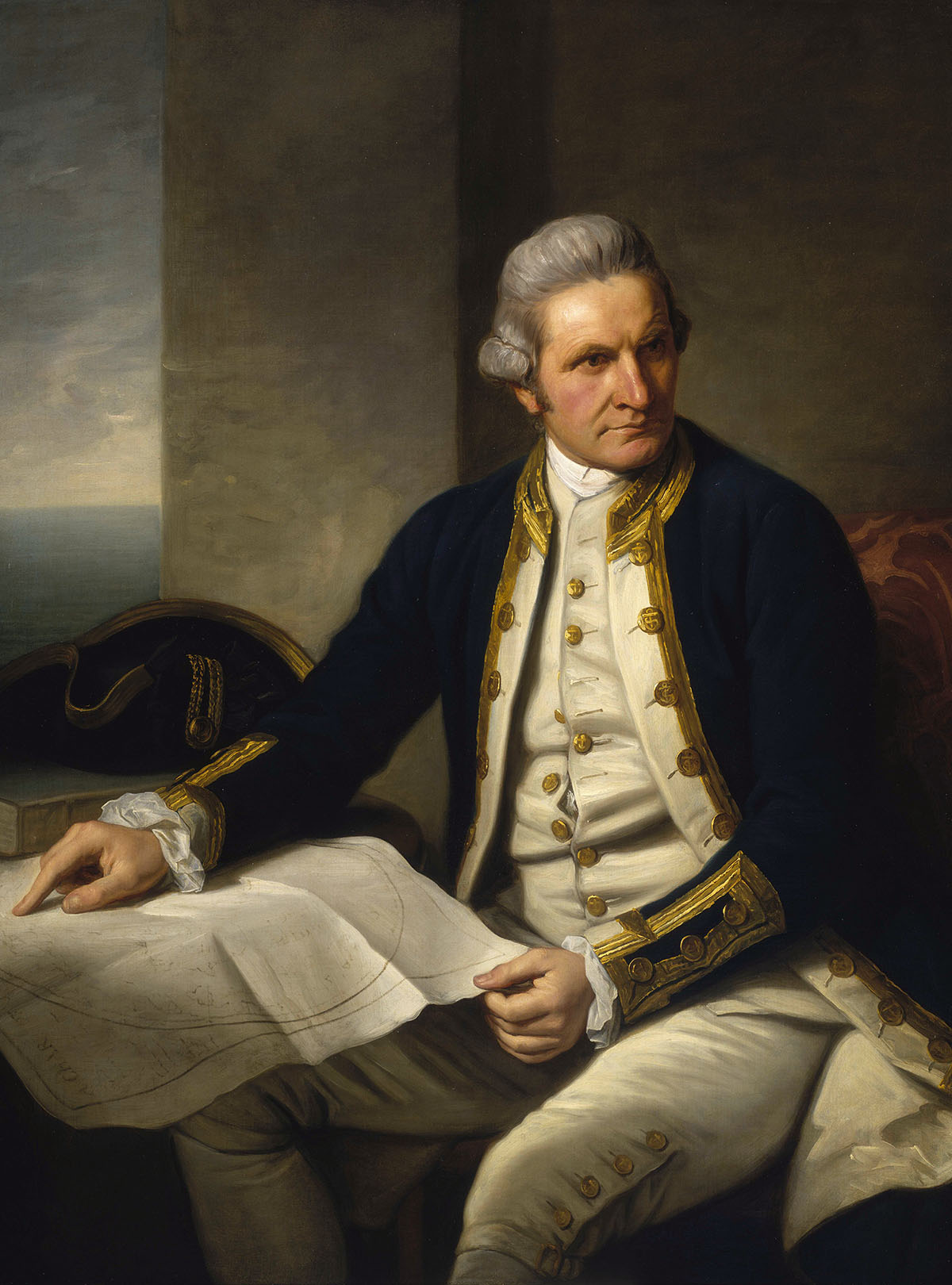

Wilson offers possible explanations for this divergence throughout the book, but he begins by emphasizing the intellectual curiosity that led some Europeans to explore the world for the sake of knowledge rather than plunder or conquest. Illustrative of this phenomenon is Captain James Cook. Wilson cleverly ties Cook’s exploits to 1776 by noting that in the summer of that year two ships left England in opposite directions. The first of these was Cook’s former ship, HMS Endeavour. In it, Cook had navigated the globe to “observe the transit of Venus: a rare astronomical event that would enable the scientists of the Royal Society to calculate the distance between the earth and the sun.” After succeeding in this quest, Cook visited numerous lands that the scientists on board studied in great detail. Wilson notes that the three botanists on the ship collected 30,000 dried specimens, which enabled them to identify more than “a hundred new genera and thirteen hundred new species.”

Unfortunately for Wilson’s thesis, the famous voyage just described occurred in 1768–71. The ship formerly named Endeavour left England in 1776 to transport Hessian soldiers to America. But Cook did leave England in the summer of 1776, this time in the HMS Resolution. Alas, after exploring numerous islands throughout the Pacific, Cook was killed in Hawaii in 1779.

Wilson argues a strong thesis, but he acknowledges early on that each WEIRDER transformation did not “spring up out of nowhere in 1776.” He implicitly acknowledges that it would be more accurate to say that these transformations occurred in the late 18th century, but his attempts to tie the changes to 1776 make the book more interesting. And it does seem to be the case that 1776 was a particularly important year—especially for Americans.

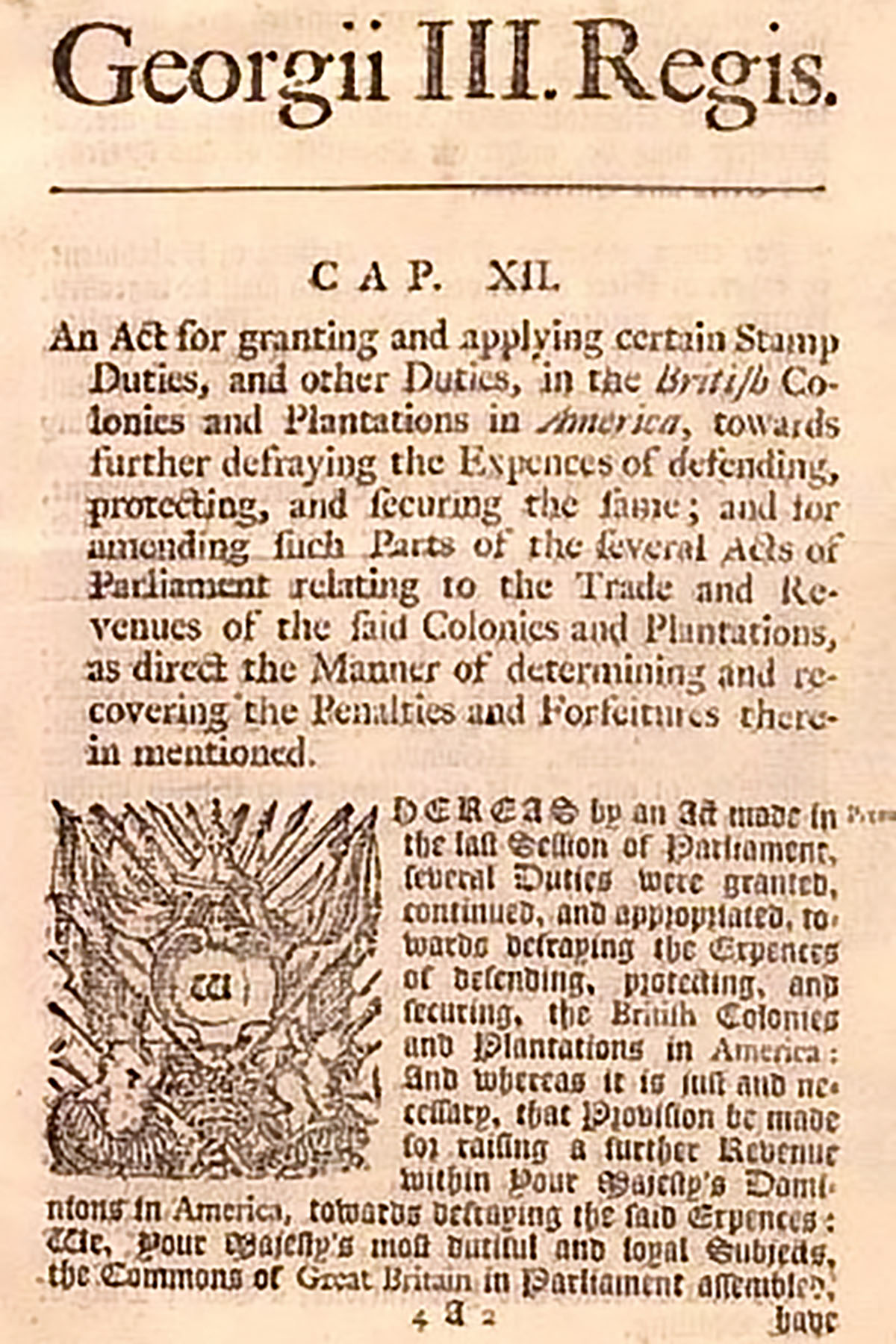

According to Wilson, in 1775 no country could reasonably claim to be a democratic republic, whereas today every country in the world (with six exceptions) claims to be democratic. Channeling his inner Ron Swanson, Wilson (who is English) contends that “the fountainhead for this transformation was the United States.” He recognizes that America’s conflict with Great Britain must be traced back to the Stamp Act Crises (1765), but Wilson highlights 1776 because the Continental Army was formally “launched” on January 1 of that year and because of General Washington’s great victory at Trenton (Dec. 25–26, 1776).

It is puzzling that Wilson spends only about two pages discussing the Declaration of Independence in his chapter on democracy, mostly dispelling myths about it. It would have helped his case to at least note that many Americans, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frederick Douglass, and Abraham Lincoln, believed that the Declaration articulates the basic principles upon which America was founded and that these principles have inspired people around the globe.

Wilson offers a brief discussion of what he calls the “great prophets of democracy” such as Algernon Sidney, James Harrington, and John Locke, and he briefly suggests that the American Puritans may have had something to do with the development of America’s experiment in self-government. In my opinion, he underestimates how democratic New England was and the impact of Protestant political theology there and elsewhere well before 1776. His lack of appreciation for earlier Protestant republicanism is illustrated by his observation, after he quotes Jefferson’s famous deathbed letter (“the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred”), that “there are no passages like that in Harrington, Sidney, or Locke.” In fact, Jefferson borrowed these striking images from a 1685 speech the English radical Richard Rumbold made before he was executed for plotting against James II.

The third transformation Wilson considers is the Enlightenment. He acknowledges, as he must, that the movement was broad, multifaceted, and often dated as lasting from 1685 to 1815. But he ties it to 1776 by describing a meal at the Baron d’Holbach’s Paris salon on February 11, 1776, and then observing that “there was more intellectual fire power sitting down for lunch in Europe on [that day] than at any time since,” including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Adam Smith, Antoine Lavoisier, Edward Gibbon, Carl Linneaus, Edmund Burke, Catharine Macaulay, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Denis Diderot. Moreover, these men and women were “connected to each other, through an international network of letters, salons, clubs, societies, magazines, taverns, and coffee houses,” and many of them understood themselves to be “engaged together in a common project.”

Wilson underestimates how democratic New England was and the impact of Protestant political theology there.

Many Enlightenment thinkers thought of themselves as using reason to bring light to darkness. To them, the Middle Ages were the dark ages, wherein “people spent all of their time burning witches, eating turnips, and dying of the plague, until early modern Europeans arrived and switched on the lights.” Wilson challenges this caricature, contending, on the one hand, that there was plenty of creativity and discovery in the Middle Ages and, on the other, that Enlightenment thinkers were not always so enlightened (especially on matters of race). Nevertheless, the era was a time of intellectual ferment and discovery in ways that continue to shape us today. For instance, it seems obvious to us to use the scientific method, educate boys and girls, think critically about the past, and “expect truth claims to be established by persuasion, not fiat.”

Some of the Enlightenment figures mentioned above played a role in the West becoming, in Wilson’s words, “Ex-Christian.” Ex-Christians reject essential aspects of orthodox Christianity even as they often remain profoundly shaped by the tradition. Ex-Christians come in different varieties, from a James Boswell who remained a professing Christian but rejected elements of orthodox theology to irenic deists like Franklin to polemical deists such as Voltaire to combative atheists like Diderot to God-haters such as the Marquis de Sade.

Most Ex-Christians are still shaped by Christian morality and ideas, such as the inherent dignity of all persons. Their doctrinal convictions are sometime even expressed in creedal form, for instance:

In this house, we believe that science is real, women’s rights are human rights, black lives matter, no human is illegal, love is love, kindness is everything.

Any departure from this contemporary orthodoxy, Wilson observes, is treated as a grievous sin. Living individuals committing it will be called to repentance, and the dead may well be “cancelled” (as Hume and Voltaire have been).

Before 1700 there were only three sources of power: wind, river, and muscle. The first is inconsistent and hard to utilize, the second is not portable, and so in practice most things were lifted, pulled, crushed, etc., by human or animal power. The 18th century saw the invention of a machine that revolutionized society—the steam engine. The first inefficient steam engine was built in 1712, but Isaac Watts’ innovations allowed for the widespread use of efficient steam power. His first commercial steam engine started running on March 8, 1776. This engine, along with advances in chemistry and metallurgy, laid the basis for the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution was responsible, in part, for what economic historians call “the great divergence.” Throughout human history, the gross domestic product per person remained roughly the same—until the late 18th century. With industrialization came an absolute explosion of wealth in Western countries, an explosion that began in Great Britain but that spread elsewhere. The scale of this increase of wealth is remarkable. Wilson observes that today “human beings consume around seventy times more goods and services than we did two centuries ago—an increase not of 70 percent but of 7,000 percent.”

Why did some countries develop more rapidly than others? Acceptance of free markets is part of the answer, and one conveniently (for Wilson’s thesis) advocated for by Adam Smith, whose An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations was published in 1776. Wilson also considers the importance of good institutions (e.g., courts that enforce contracts), colonization, culture (a desire to explore the unknown, innovate, disseminate knowledge, etc.), and that the geography of Europe resulted in fragmented countries that competed with each other. Whatever the exact combination of causes, there is no doubt that the late 18th century saw an explosion of wealth in the West that continues to shape us today.

Of course, not everyone celebrated all the transformations discussed above. Romanticism is often treated as a reaction to the Enlightenment. Wilson acknowledges that many iconic figures of Romanticism were children in 1776, but he makes a reasonable argument that Rousseau may be understood as an early Romantic and that his last book, The Reveries of the Solitary Walker, was based on strolls he took around Paris from 1776 to 1778. The work, Wilson suggests, “shows many of the hallmarks of Romanticism … inwardness, imagination, individuality, inspiration, innocence and intensity.”

Wilson is teaching pastor at King’s Church London, and his Ph.D. is in theology. He informs his readers in the first chapter that his “primary motive in writing [this book] is to help the church thrive in a WEIRDER world,” but the bulk of the work could have been written by a historian simply attempting to explain the massive transformations that occurred in the late 18th century. The book’s last two chapters are pastoral in nature, suggesting ways in which Christians did and can respond to the transformations he identifies.

There was plenty of creativity and discovery in the Middle Ages, and Enlightenment thinkers were not always so enlightened.

Although Wilson describes the transformation of many Westerners into Ex-Christians, he recognizes that countless remained committed to orthodox Christianity and engaged their cultures in important ways. He identifies three such ways he hopes will inspire Christians today. The first is the profound celebration of God’s grace that flourished in the 1770s. This is reflected well in the marvelous hymns from that era, such as “Rock of Ages” and “Amazing Grace.” Second, he highlights the increasing commitment of believers to end the enslavement of men and women, a commitment nicely illustrated by Lemuel Haynes’ pamphlet Liberty Further Extended, or Free Thoughts on the Illegality of Slave-Keeping. Haynes, the first African American to be ordained a pastor, wrote this pamphlet in 1776. Finally, Wilson observes that Christians like Johann Georg Hamann began to make thoughtful criticisms of the excessive rationalism and materialism found in the work of some Enlightenment luminaries.

The final chapter offers ways in which Christians might respond to our WEIRDER world. Wilson observes that many of the benefits of this world—“life expectancy, wealth, safety, education, health choice, and rest”—can entrap rather than free us. Many of us are so consumed with the pressure of privilege, constructing identities, and pursuing status that we feel overwhelmed. The temptation to compare ourselves constantly with others on social media and the possibility of being cancelled if we don’t observe today’s orthodoxies doesn’t help. Christians should help our fellow citizens understand that the Gospel of grace provides true freedom. They need to present the “Christian vison of liberty in all its fullness: spiritual and physical, freedom from and freedom to, confronting the flesh within and the power without.”

Wilson suggests as well that Christians have much to offer those Americans who are (or think they are) post-truth. The Christian understanding of Creation, Incarnation, and Resurrection makes it possible for us to

know what is true, not just about God, but about creation, humanity, history, and the future. Creation is coherent, created with a purpose by an all-loving God. Every human being possesses inestimable value simply by bearing God’s image. History is heading somewhere under divine guidance rather than going around in circles.

Remaking the World is a remarkable book. One shouldn’t take Wilson’s strong thesis too literally, but he identifies important transformations that came about or at least began in the late 18th century that continue to impact the West today. The book offers a serious historical argument, but it is also fun to read because of Wilson’s ability to tell interesting stories, relate fascinating anecdotes, and make improbable connections.