“Kris, I need to know how many books.”

Vehicle, boxes, packing materials, hand truck (I wasn’t going to make that mistake again—always bring a hand truck). Books. To a librarian, their names and forms are important, but before they become part of a collection, they must be numbered. I had known the generous donors, James and Mary Holland, as long as I had worked at the Acton Institute: 15 years. Well, not “known”—known of, never met. I knew their work and by extension something of their books. Collections live and breathe, expand and contract. Expansion was coming, and for a librarian that is thrilling, but as with breathing, it could also be terrifying not knowing how deep or shallow it would be.

There was a time when a mere magazine could shake up institutions and sway generations. Have we sacrificed scholarship for persiflage and influence for “likes”?

Two days later, Kris Mauren, president of the Acton Institute, had some rough numbers for me.

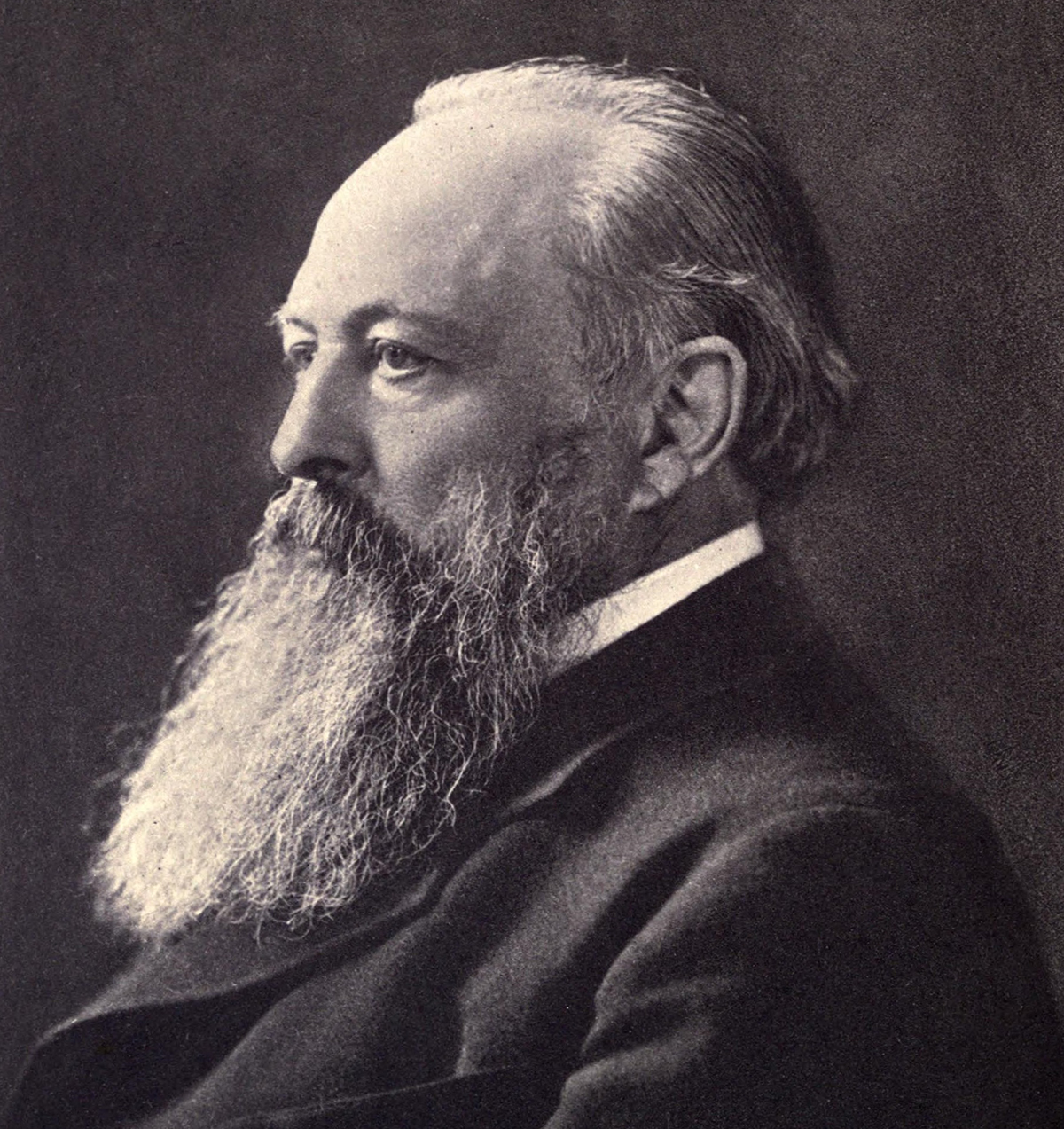

After two hours in the air and two hours on the road, I found myself in the Hollands’ driveway. James and Mary are retired academics who have made outstanding contributions to the intellectual history of Catholicism. My first introduction to Lord Acton was a slim volume published by the Acton Institute titled The History of Freedom, which collected two of Acton’s finest lectures with a historical introduction by James C. Holland, whom I now, finally, had the pleasure of meeting.

James and Mary were both delights, their home charming, and their books treasures. We spent the afternoon packing books to take back to the Institute, mostly historical works, and of those mainly British history. Many were volumes featuring Lord Acton’s closest allies and leading adversaries, including a few figures who could rightly claim to have been both. Shelves were emptied and the truck filled and then Mary reminded James not to forget about the basement. The basement!

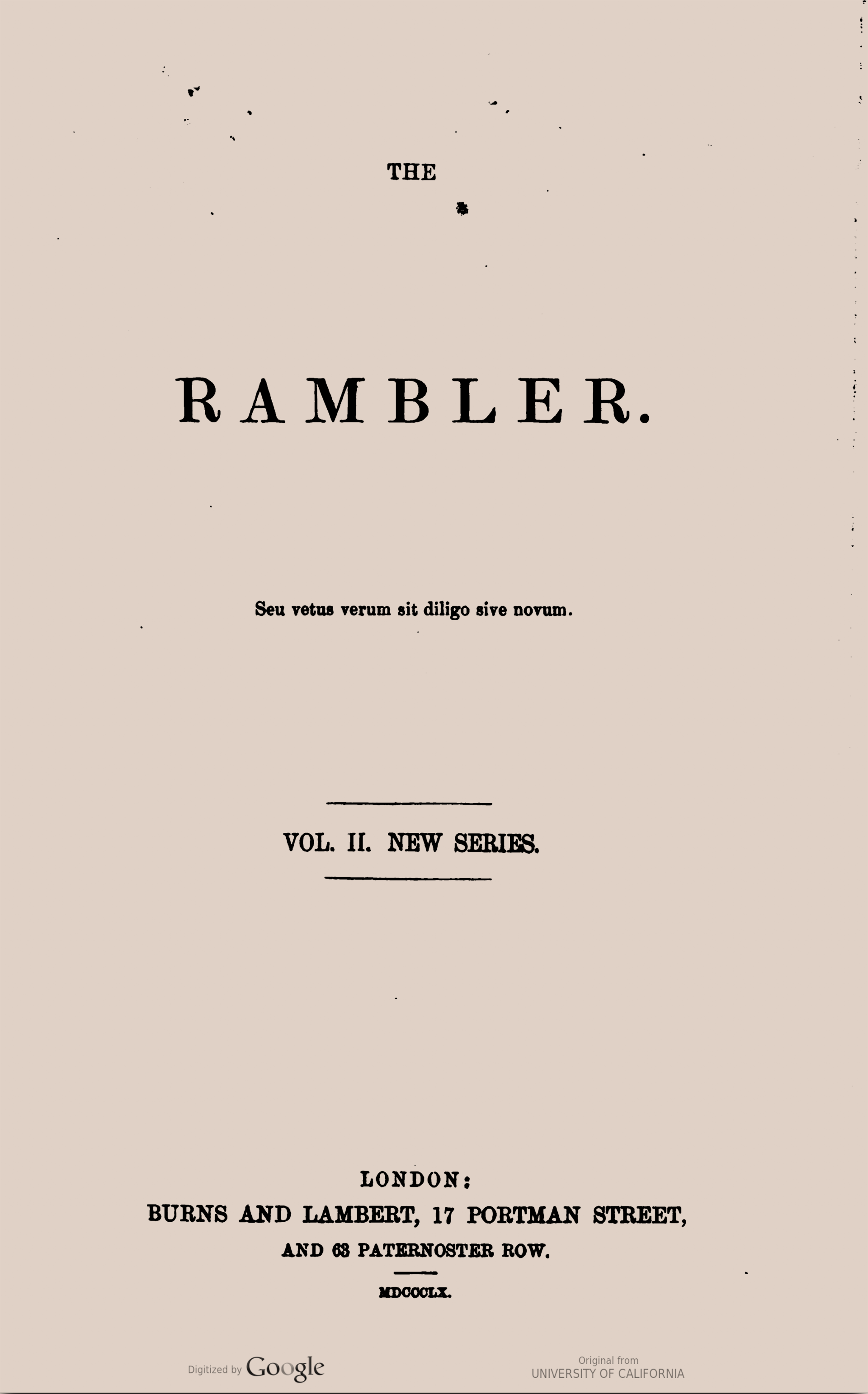

In the basement was the greatest treasure of all—The Rambler. A complete bound set of the Catholic magazine so intimately associated with Lord Acton, annotated by James and Mary themselves. The annotations are incredible. A guide through the vagaries of its composition. Bylines, so often absent in Victorian periodicals, carefully penciled in the margins! I loaded The Rambler set last, and loaded it best. Riding in the passenger seat, shotgun, all the way back to Grand Rapids.

From the perspective of the 21st century, this may all seem rather strange. Why would scholars carefully pour over and study a magazine? Why would a librarian (myself), even one most eccentric, give pride of place to a magazine over so many significant and rare books? The answer is twofold: the times and the man. The times were Victorian, and the man was Lord Acton.

A Man of Many Vocations

Few live as synchronically with their times as did Lord Acton. He was three years old when Queen Victoria assumed the throne, and lived only a year after her passing. Acton’s heritage was aristocratic, Catholic, and cosmopolitan. Five years before his birth, the Catholic Emancipation Relief Act of 1829 was enacted allowing for his full participation in England’s public life. In 1850, when Acton was just 16, Pope Pius IX would issue the papal bull Universalis Ecclesiae, “restoring in England the ordinary form of ecclesiastical government, as freely constituted in other nations.” Acton’s was thus the first generation of English Catholics since the Protestant Reformation to live their adult lives with full rights as citizens and ordinary church governance as Catholics.

The legacy of civil marginalization and ecclesial irregularity, however, could not be erased by a mere stroke of a pen by parliament or even pope. English Catholicism had become deeply isolated and inward looking, as the French historian Élie Halévy observed: “Catholics by nature or choice were something of an interior emigration, and the history of their advance cannot be considered as forming an integral part of English history.”

Acton’s early education, both Catholic and cosmopolitan, gave him a broader perspective than most English Catholics of his day. He studied in France with Mgr. Felix Dupanloup, in England at Oscott with Cardinal Wiseman, and finally in Munich with Europe’s foremost Catholic historian, Ignaz von Döllinger. It was from Döllinger that Acton developed his vocation as a historian and was schooled in the latest historical methods. Despite his emerging vocation as a historian, his stepfather began to apprentice Acton in Liberal Party politics.

Acton rightfully saw journalism as a powerful venue for both scholarship and influence.

His brief parliamentary career almost immediately took a back seat to his emerging passion for journalism. Why would a historian want to be a journalist? The journalism of mid-19th-century England was very different from the journalism of today. Librarian W. F. Poole describes the scene well:

The best writers and great statesmen of the world, where they formerly wrote a book or a pamphlet, now contribute an article to a leading review or magazine, and it is read before the month has ended in every country in Europe. … Every question in literature, religion, politics, social science, political economy … finds its latest and freshest interpretation in the current periodicals.

Magazines and journals were the podcasts of their day, so Acton assumed the editorship of The Rambler in 1859. He rightfully saw journalism as a powerful venue for both scholarship and influence. This description, given in The Rambler’s final issue, echoes Poole’s description of the scope and energy of Victorian magazines, while also relating Acton’s aspiration to shape and give voice to a newly liberated English Catholicism:

The Rambler was commenced on 1st of January 1848 as a weekly magazine of home and foreign literature, politics, science and art. Its aim was to unite an intelligent and hearty acceptance of Catholic dogma with free enquiry and discussion on questions which the Church left open to debate and while avoiding, as far as possible, the domain of technical theology, to provide a medium for the expression of independent opinion on subjects of the day, whether interesting to the general public or especially affecting Catholics.

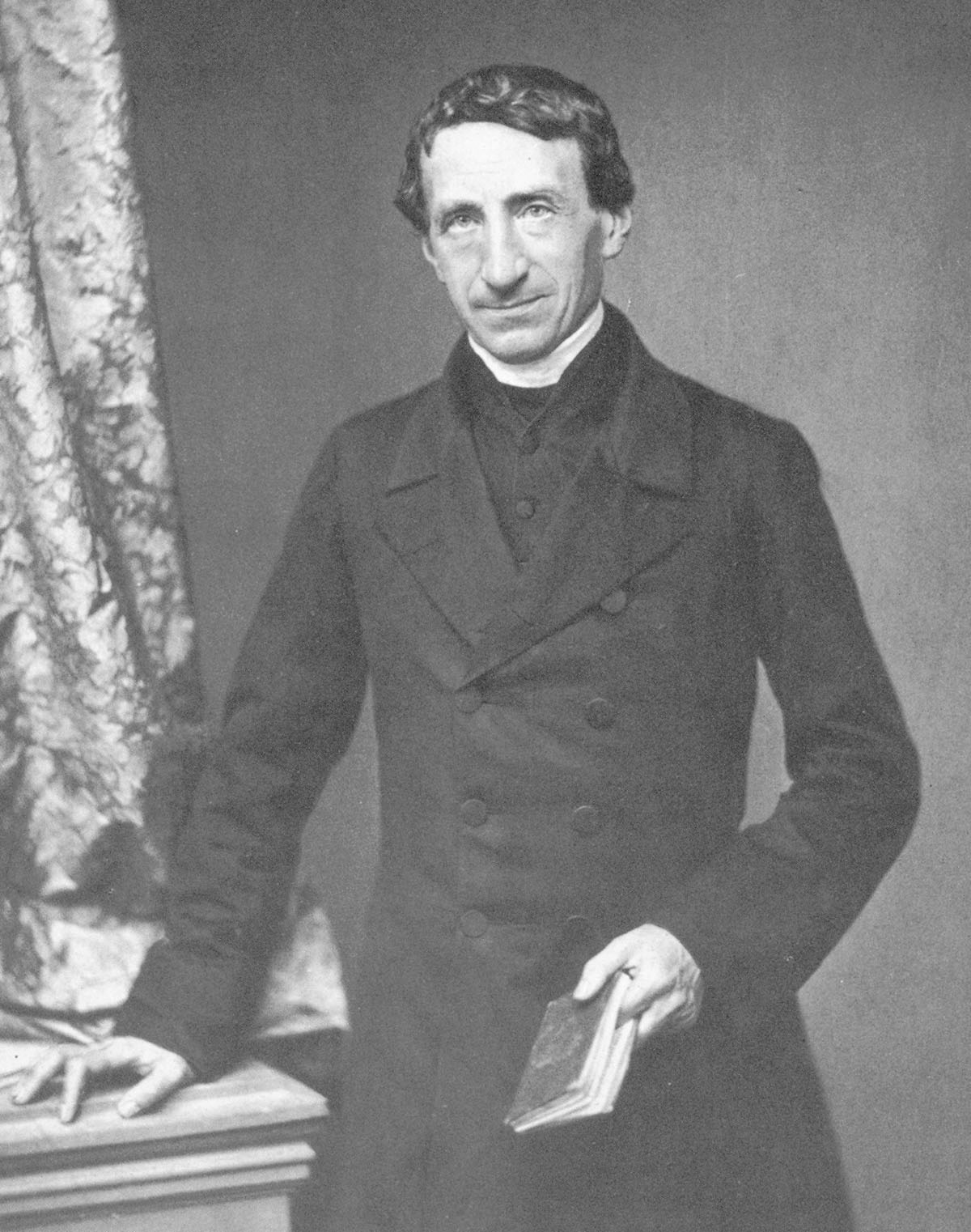

The contributors to The Rambler shared with (now) St. John Henry Newman, himself a contributor and briefly editor, the conviction that the Church should fear no knowledge, “for all branches of knowledge are connected together because the subject matter of knowledge is intimately united in itself, as being the acts and work of the creator.”

This was more controversial than one might imagine. English Catholicism at the time was either deeply insular and narrow or belligerent and triumphalist. Acton recounted a vivid example of this triumphalism from his studies at Oscott, recalling how Cardinal Wiseman paraded recent converts to Catholicism from the Church of England around the school: “The converts used to appear amongst us, and he seemed to exhibit their scalps.” Acton thus saw the role of The Ramblerto fight on two fronts: “with those who are of little faith and with those who have none at all—with those who for the sake of religion fear science, and with the followers of science who despise religion.”

Threat of ecclesiastical censure loomed constantly over The Rambler.

Obedience vs. Principle

Threat of ecclesiastical censure loomed constantly over The Rambler. Bishop William Ullathorne wrote to Cardinal Alessandro Barnabò, then prefect of the Congregation Propaganda Fide in Rome, “The Rambler demands the greatest and most prompt attention” for “if these writers are not themselves sceptical, and I believe they are not, but only delight in being bold, daring and provoking, from pride of intellect, yet the result may ultimately be to awaken scepticism in minds that are ill-instructed, weak and pretensious.”

At one point, Newman assumed editorship to conciliate The Rambler’s critics. When his article “On Consulting the Laity on Matters of Doctrine” was published in its pages, it was delated to the Congregation of the Index in Rome. Acton had to resume editorship to take the heat off Newman. One of its most prolific contributors, the Catholic convert Richard Simpson, was even denied absolution after confession because of his work for The Rambler.

The field of controversy was over all Wissenschaft—the systematic body of facts and knowledge. The Rambler’s editorial policy was open to knowledge from all academic disciplines, and its contributors freely drew on them in a disinterested pursuit of truth. This alarmed ecclesial critics who feared science unconstrained by religious authority. In a letter to his fellow contributor Simpson, Acton wrote:

In politics as in science the Church need not seek her own ends. She will obtain them if she encourages the pursuit of the ends of science, which are truth, and of the State, which are liberty. We ought to learn from mathematics fidelity to the principle and the method of inquiry and of government.

There were conflicts over philosophy, theology, politics, art, and, most consistently and constantly, history. Today’s dominant narratives of the supposed “conflict between religion and science” are centered on natural science in general and biological evolution in particular, but the past is another country altogether. John Lyon, writing in a 1972 article inChurch History titled “Immediate Reactions to Darwin: The English Catholic Press’ First Reviews of the ‘Origin of the Species’” finds surprising points of consensus between the reviews by Simpson in The Rambler and Canon W. Morris in its ultramontanist rival the Dublin Review.

They were able to point out what seemed to them to be Darwin’s unwarranted jump from facts supporting an evolutionary viewpoint to natural selection—simple chance—as the sole logical explanation of the observed phenomena.

For Lyon, The Rambler review is a marvel as so much Catholic reaction to Darwin at the time was simply “inarticulate horror”: “Richard Simpson saw the issues, faced them as best he could, made what distinctions were possible, and then wrote forcibly of his perception.”

Many leading conservative Catholic churchmen failed to appreciate such constructive engagement. They cultivated a deep suspicion of modern civilization, which they viewed as fundamentally antagonistic toward the Church. Reflexive hostility to so much of the development in the sciences across disciplines was embraced as a strategy in that struggle—a misguided attempt to undermine the Church’s enemies by cutting them off from the source of their strength. Acton was finally pushed into a corner he felt he could not escape by any means other than ceasing The Rambler’s publication. Newman suggested a clerical board of censors be adopted to convince hostile bishops they had nothing to fear. He drew up a list of four priests who could make up such a board, including himself and Acton’s teacher Döllinger. Acton dismissed the idea because all the named priests were alsosuspect in the eyes of hostile bishops.

There was still some fight in Lord Acton, however. First he cheekily approached the Dublin Review with a merger proposal. Upon being rebuffed, he made a final defiant stand by founding a new magazine that Gertrude Himmelfarb describes deliciously in her biography Lord Acton: A Study in Conscience and Politics:

With the old staff and old ideas, the new title and format deceived no one, and the Home and Foreign Reviewinherited the ill-will formerly directed against the Rambler. From the first issue, when it insisted upon speaking of Pope Paul III’s “son” rather than the conventional euphemism of “nephew,” until the last stormy issue just two years later, the journal carried on an incessant feud with the hierarchy.

Bishop Ullathorne’s observation that some of The Rambler’s contributors took “delight in being bold, daring and provoking” was certainly true of its successor, Home and Foreign Review. Acton’s closing article, to which he affixed his own name, “Conflicts with Rome,” reveals no “skepticism” or “pride of intellect,” but rather a resolute faith and commitment to the service of truth:

It would be wrong to abandon principles which have been well considered and sincerely held, and it would also be wrong to assail the authority that contradicts them. The principles have not ceased to be true, nor the authority to be legitimate because the two are in contradiction. … I will not challenge a conflict which would only deceive the world into the belief that religion cannot be harmonized with all that is right and true in the progress of the present age. But I will sacrifice the existence of the Review to the defense of its principles, in order that I may combine the obedience which is due to legitimate ecclesiastical authority, with an equally conscientious maintenance of the rightful and necessary liberty of thought.

Lord Acton would continue to write learned and influential articles in the leading journals of his day, but he would never play the leading editorial role for any publication as he had for The Rambler and its successor the Home and Foreign Review. His vision of an English Catholicism that embraced both faith and science alongside legitimate authority, and human freedom over and against insularity and triumphalism, was one not realized in his lifetime. It was one that much of Catholic Europe failed to attain in the 19th century.

Is such a vision perhaps too bold and daring for the world this side of paradise? Or was it simply too much to expect a magazine to secure intelligent and hearty acceptance of Catholic dogma alongside a spirit of free enquiry?

What Should a Magazine Cost?

Six years after the shuttering of the Home and Foreign Review, Lord Acton was still thinking about the power, promise, and peril of Catholic magazines, this time not in England but in Rome.

Writing for the North British Review in 1870, Acton penned “The Vatican Council,” a fascinating study of the First Vatican Council and its leading personalities. Early on, Acton references the profound influence of the Jesuit magazine La Civiltà Cattolica, which was founded in 1850, the same year Pope Pius IX returned to Rome in the wake of the French Army’s restoration of the Holy See’s temporal power, which had been contested since the Garibaldian revolutionary upheaval of 1848.

Acton argued that the editors of the new magazine did not identify themselves primarily with their religious order, since “their General, Roothan, had disliked the plan of the Review, foreseeing that the Society would be held responsible for writings which it did not approve, and would forfeit the flexibility in adapting itself to the moods of different countries, which is one of the secrets of its prosperity.”

La Civiltà Cattolica and its editors were taken under the pope’s protection instead:

The Pope appointed them on account of that devotion to himself which is a quality of the Order, and relieved them from some of the restraints which it imposes. He wished for something more papal than other Jesuits; and he himself became more subject to the Jesuits than other pontiffs. He made them a channel of his influence, and became an instrument of their own.

Acton is clearly unsympathetic with the editorial line at Civiltà Cattolica, but the attention he paid to it and the importance he placed on it in shaping Catholic opinion in Rome and the wider Catholic world in the 20 years leading up to the First Vatican Council is revealing. He clearly still believes in the transformative power of magazines, especially if its readers include the pope.

Acton was right in understanding magazines as a path to influence in his own day. That he lost the battle does not mean that the field on which it was contested wasn’t the high ground. Acton’s great teacher Döllinger once said that he didn’t believe his student would ever write a book unless he wrote one before he was 30. The Home and Foreign Reviewpublished its last issue in 1864, just a few months after Acton’s 30th birthday. His biographer Roland Hill titled the chapter on this period of Acton’s life “Editor in Chains.” Was his bondage to the magazine medium worth it—to him or to those who try and carry on his legacy?

Gertrude Himmelfarb, writing in 1952, said,

It is only now, while his background recedes even further from sight, that Acton himself is beginning to come, for the first time, clearly into view. It appears that we are privileged to see and understand him as his contemporaries never did. He is of this age more than of his. He is, indeed, one of our great contemporaries.

Himmelfarb attributes this to the post–World War II confrontation with the horrors of German Nazism and Soviet Communism that left little room for crass optimism or materialism that dominated so much of Acton’s century. That naïve, reductionistic liberalism finds a realist alternative “religious in temper, which is able to cope with the facts of human sin and corruption … because Acton was never taken in by history, he can speak with authority when history runs amok.”

Acton’s vision of an English Catholicism that embraced human freedom over and against insularity and triumphalism was one not realized in his lifetime.

This is most certainly true. Acton’s moral vision has never been more resonant. The ideological evils he identified, such as radical egalitarianism, socialism, and nationalism, cannot be confronted by those of little faith or none at all. Much of that moral vision, however, is literally bound to its time—regular intervals of it—within periodical slices of Queen Victoria’s reign.

This is the tradeoff inherent in packaging ideas to be “read before the month has ended in every country in Europe.” This has become more severe in the age of the internet. Information and influence today ride on algorithmic tides moving according to their own principles. These are obscure, devoid of the moon’s constancy. There is no astrology for the information age.

Acton inspired many faithful students who repackaged so many of his insights that were first circulated in magazines. Biographies such as Himmelfarb’s and Hill’s place them in context. Anthologies such as Rufus Fears’ three-volume Selected Writings of Lord Acton present them by topic. My own Lord Acton: Historical and Moral Essays is an attempt to arrange lectures, essays, and reviews written during his life into an intelligible outline of his understanding of the universal history of freedom. This sort of work will be more difficult for students of future thinkers who write in digital media in our digital age. Link rot, the trend of hyperlinks over time to lose their referent file, page, or server, may make it impossible. Magazines, in all their 19th-century splendor, may still be the best trade-off an author can make to influence the future.

The Rambler Effect

Twentieth-century editors of American religious magazines placed such bets and hit the jackpot. The intellectual development and popular imagination of Christians in the United States was shaped by magazine editors at Christian Century, Commonweal, and Christianity Today. These magazines centered on religious traditions that have since become the standard “identities” of American religious demography: mainline, Catholic, and evangelical.

Christian Century began its life under another name as a Disciples of Christ magazine in the late 19th century. With the new century, it adopted the new name and, in a few years, a nonsectarian identity. It became the flagship magazine of the mainline, espousing theological liberalism and the Social Gospel.

Christianity Today, established in 1956, played a similar role in evangelicalism. An early editorial explained its origin in “a deep-felt desire to express historical Christianity to the present generation. Neglected, slighted, misrepresented—evangelical Christianity needs a clear voice, to speak with conviction and love, and to state its true position and relevance to the world crisis.” This neglect and misrepresentation were not primarily from secular elites but rather at the hands of the Protestant mainline establishment.

The Catholic magazine Commonweal was different. It did not foster the emerging trans-denominational religious identities as Christian Century and Christianity Today did. What it did do was contribute to an emerging identity of American Catholicism. A part of the larger Church but also a unique expression of it. Founded in 1924 as an independent Catholic journal, it was edited by laypeople. Its original board called themselves “the Calvert Associates” after the 1st Baron Baltimore and his descendants, who were instrumental in the founding of colonial Maryland. They understood Catholicism as compatible with the American experiment in ordered liberty and believed American Catholics had and should continue to make contributions to it.

All three of these magazines remain in print well into the 21st century. Each has continued to evolve along the trajectories of their constituencies and the sensibilities of their editors. In reaction to these dynamics, many imitators, rivals, and innovators sought out arbitrage opportunities. One entrepreneurial priest, Fr. Richard John Neuhaus, attempted a brilliant synthesis with the establishment of First Things in 1990.

First Things was ecumenical from the start, seeking to advance “a religiously informed public philosophy for the ordering of society.” Fr. Neuhaus was uniquely situated to cultivate the best writing from mainline, Catholic, and evangelical contributors owing to a unique and remarkable career. He began his ministry as a Lutheran pastor in the conservative Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, transferred to ministry in the Lutheran mainline, and was finally received into the Catholic Church and ordained a priest. Coordinating the contributions of such diverse writers, including in the mix many Jewish contributors, remains an inspiring editorial feat.

Neuhaus’ skills as a writer, editor, and networker were the secret to the magazine’s success, but even he could not prevent tensions from boiling over. Lord Acton’s biographer Gertrude Himmelfarb resigned from the board of the magazine after a symposium titled “The End of Democracy” published in November of 1996. She described the situation in the pages of Commentary a few months later:

The editors of the religious journal First Things, citing the “judicial usurpation of politics,” put into question the very “legitimacy” of the American democratic system and invited a number of writers to consider the steps, not excluding force, which a citizen might be morally entitled to take against “the existing regime.” The symposium, with its explicit invocation of the analogy of Nazi Germany, and its echoes of 1960’s-style radicalism, prompted the outraged resignation of a number of prominent conservatives from the magazine’s board.

First Things continued under Fr. Neuhaus until his passing in 2009 and continues today. Its quest for a religiously informed public philosophy remains but with a narrower set of voices than in its earliest days. The 21st century has seen much great writing in religious magazines of varying vintages, but the editorial vision seems small when compared to the ambitions of the 19th and 20th centuries. What is needed in the future are magazines that reach beyond our sects, our religious “identities,” and partisan politics. To take a page from Lord Acton, they must be dedicated to the disinterested pursuit of truth and human freedom in all its dimensions.

The Gift That Keeps On

After the books were all packed and The Rambler’s seatbelt securely fastened in the passenger seat, I had dinner with James and Mary Holland. It was lovely, saturated with engaging conversation. I thanked them both for their wonderful gift and their generous hospitality, drove a short distance to my hotel, and went to bed.

I couldn’t sleep.

I went out to the truck and grabbed the box containing The Rambler set. I opened it and leafed through a volume. Exhaustion settling in, I packed them back up but left them in the room for the night. It didn’t feel right to leave them out in the cold.

The next morning, I woke up and checked my email. There was a message with an attachment from my editor. It was notes for revisions for a magazine article I had sent him before leaving Grand Rapids. I accepted all changes and made a few tweaks to the manuscript before emailing him back. I closed the laptop and looked across the room to the box containing The Rambler.

“There’s articles left in you yet.”