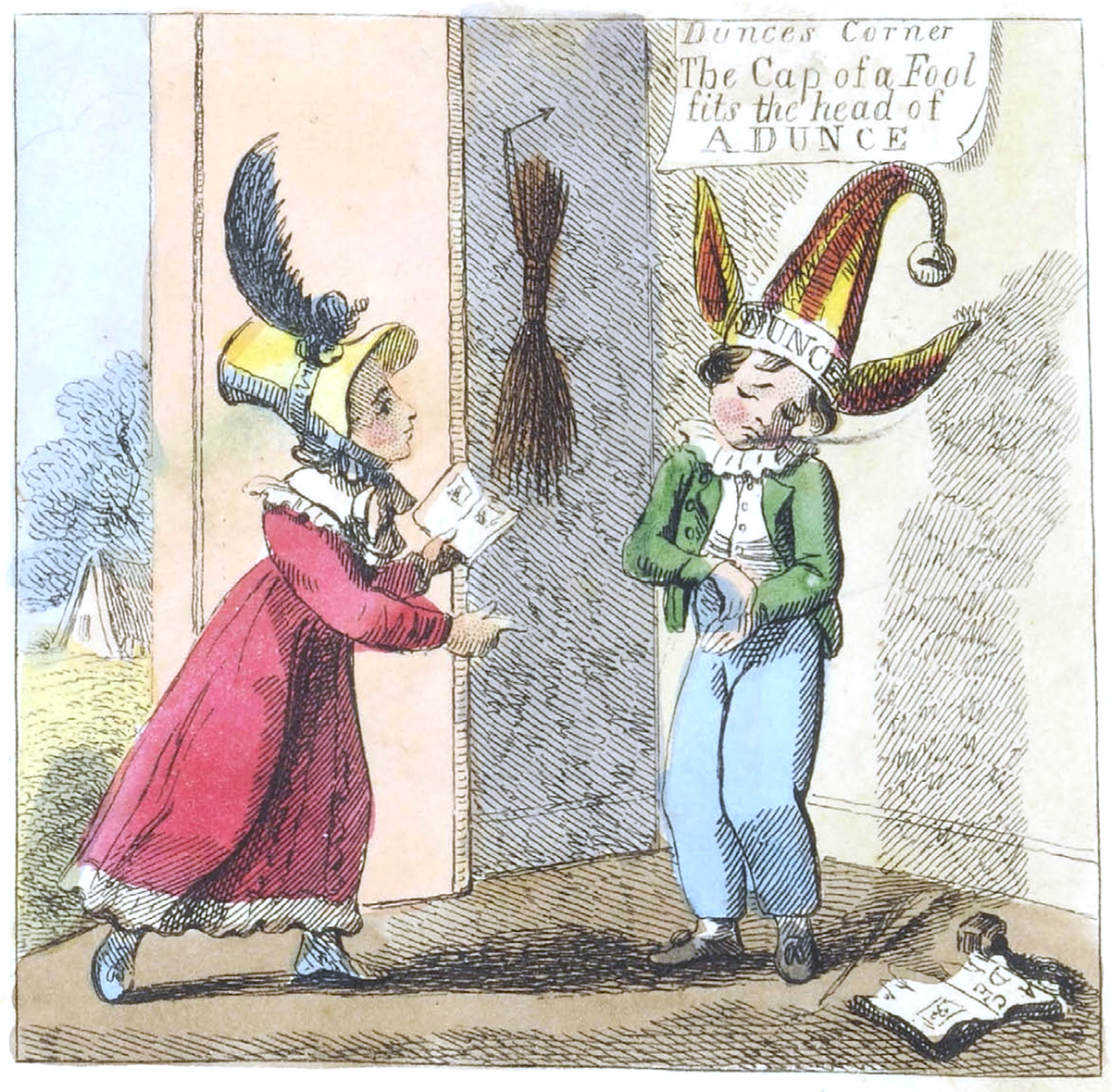

"When a true genius appears in the world, you may know him by this sign, that the dunces are all in confederacy against him."

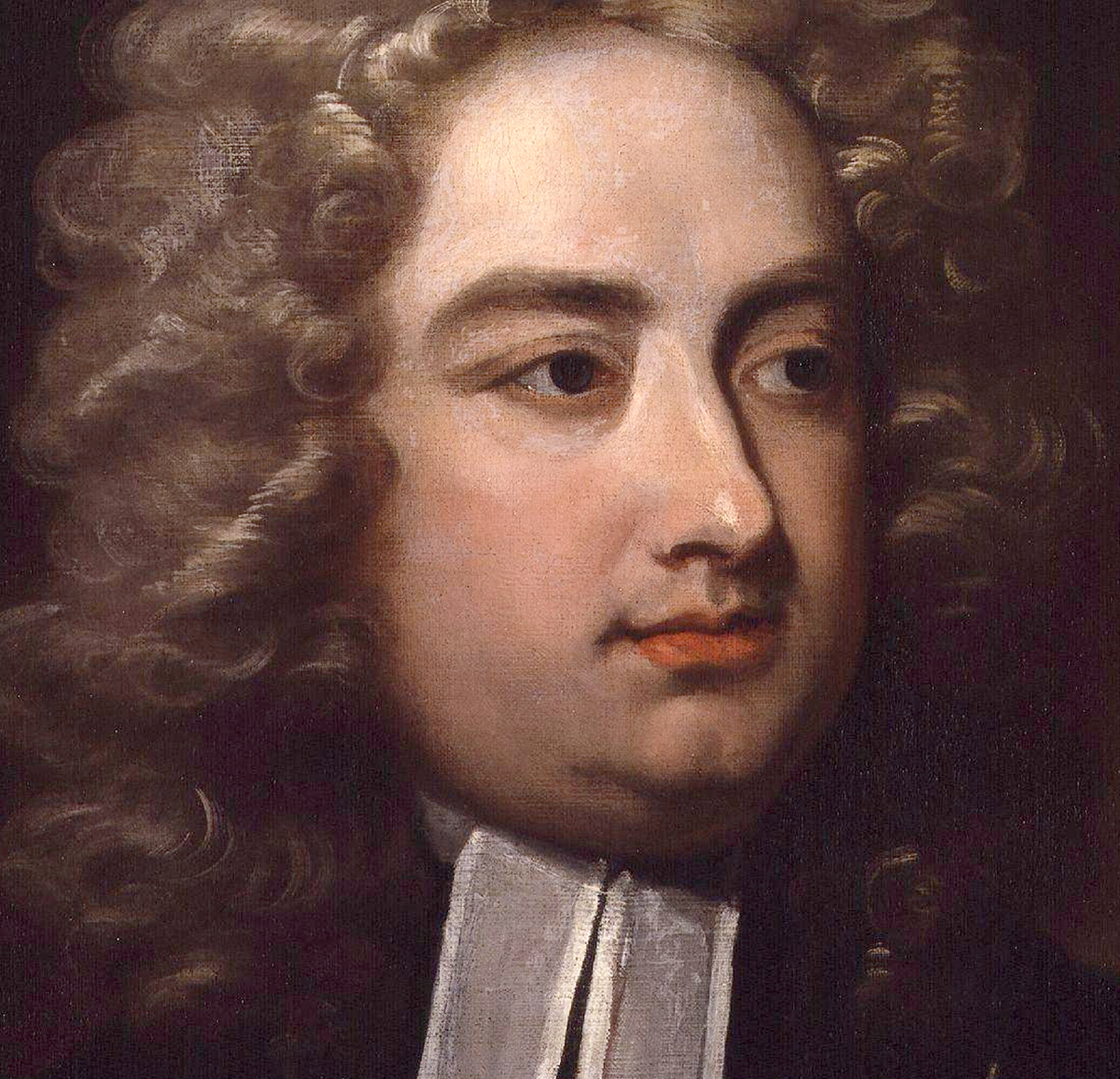

Jonathan Swift

Various Thoughts, Moral and Diverting

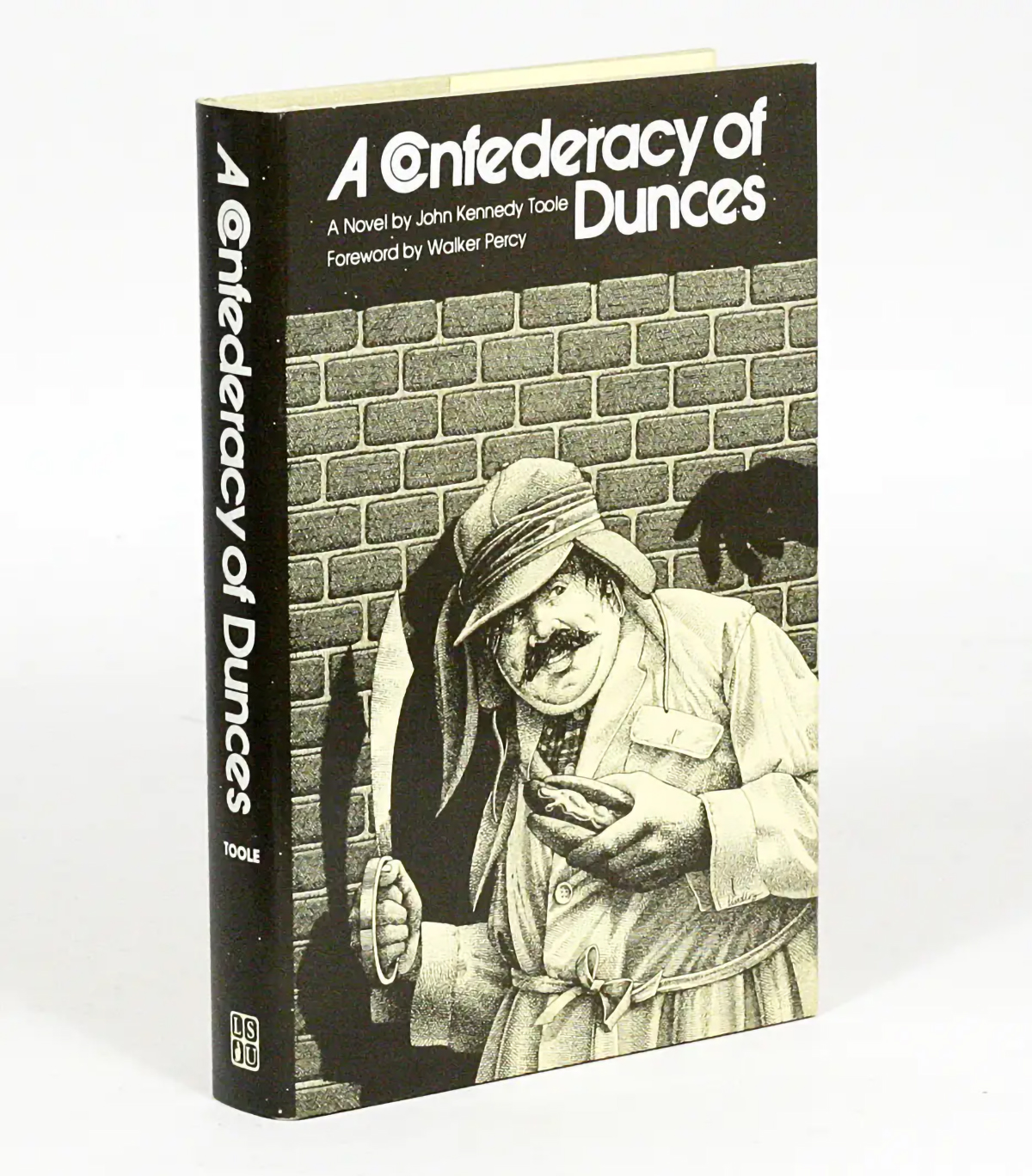

In the Winter 2023 issue of this publication, I addressed briefly the impact of Don Quixote on the author of A Confederacy of Dunces. In that essay, I referred to the latter novel as “a miracle of art, conceived and constructed by genius but founded on scholarship that is still largely unrecognized.” We know as a fact that, during the academic year 1958–59, John Kennedy Toole took a graduate seminar at Columbia University on Augustan satirists. But while the titular and epigraphic connection to Swift is easily acknowledged, little has been said about what else Toole might have learned from him. In this essay, then, I want to explore and comment on Swift’s impact on Toole, for the purpose of advancing Toole’s reputation as a learned author and correcting some convenient misunderstandings. This effort will require some stamina on the reader’s part, and some interest in the finer points of scholarship.

What does an 18th-century High Church Anglican skewer of intellectual pretensions and a 20th-century Roman Catholic professor lost in the cosmos have in common? The eternal struggle against dunces.

Jonathan Swift’s Various Thoughts, Moral and Diverting (1706) is a loose collection of maxims written in the style of La Rochefoucauld. When he penned the sentence that would become the epigraph to A Confederacy of Dunces, Swift was linked in the English mind to the statesman and adviser to Charles II Sir William Temple. The famous quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns was going strong in the 1690s, when Swift was serving as Temple’s secretary. Swift took offense at the rough treatment that Temple, a leading Ancient, received from two Moderns, William Wotton and Richard Bentley. An Ancient himself, he ridiculed them in The Battle of the Books. Wotton, eager to return fire, dismissed A Tale of a Tub (bound in the same 1704 volume as The Battle of the Books) as “irreligious” and “crude.” The exchange occurred after Temple’s death in 1699, so it is natural to associate William Wotton and Richard Bentley with the dunces of Swift’s maxim.

Swift reserved the word genius for a select few, including his friend Alexander Pope and, in his 1714 poem “The Author upon Himself,” himself:

By an old red-pate, murd’ring hag pursued,

A crazy prelate, and a royal prude;

By dull divines, who look with envious eyes

On ev’ry genius that attempts to rise …

Confessing to “the sin of wit, no venial crime,” the Ireland-exiled Swift continued to fire back at the vicious, the mad, the prudish, and the dull.

The conflict of genius and dunce returns in Gulliver’s Travels (1726), in Gulliver’s visit to Glubbdubdrib, the sorcerer’s island where the ghosts of Homer and Aristotle “appear at the Head of all their Commentators.” Gulliver describes the conversation:

I introduced Didymus and Eustathius to Homer, and prevailed on him to treat them better than perhaps they deserved, for soon he found they wanted a Genius to enter into the Spirit of a Poet. But Aristotle was out of all Patience with the account I gave him of Scotus and Ramus, as I represented them to him, and he asked them whether the rest of the Tribe were as great Dunces as themselves.

“Genius,” as used with respect to Homer, establishes the “Spirit” of a true poet, which none of the commentators can “enter into.” Adding to the humiliating spectacle, the notion of the man who wrote Nicomachean Ethics losing “all Patience” is a master stroke, heightened by an equal-opportunity swipe at two “Dunces”: the Protestant Ramus and the Catholic Duns Scotus.

As a master ironist, Swift might be compared to an all-star pitcher who commands an overwhelming arsenal of pitches. He can throw you the straight heat at 100 mph, or he can uncork a slow sweeper that catches you off-balance and makes you fall down swinging. To describe his ironic game with readers, critics have used such terms as “entrapping” and “vexatious,” the latter following from a well-known letter to Pope, dated September 27, 1725, in which Swift confided that he wanted to “vex the world rather than divert it.” For all its variety, though, Swiftian irony is invariably linked to the wisdom of Ecclesiastes and informed by a keen Protestant ear for how we rationalize unspeakable behavior. It is a constant trial, all rather humbling and humiliating.

For Swift, then, the opposition of genius and dunce rarely survives the strain of experience. The mathematical geniuses of Laputa are, in Swift’s view, dunces of the highest order, estranged from their own senses. Likewise, the choice of Yahoo or Houyhnhnm is a vexatious and false choice. The epigraph to A Confederacy of Dunces carries with it a similarly vexatious air. Ignatius J. Reilly sees himself as a “genius,” but the gap between Ignatius’ image of himself and the world’s response to him tells a different story. It suggests that Ignatius, like Gulliver, is a bit of a dunce.

The Scholar of Fortuna

A Confederacy of Dunces is a vexatious, satirical parody of Kennedy-era America, written while Vatican II was in full swing, by a Southern Catholic who was far more of an outsider than the middle-class novelists who triumphed in New York—Mailer, Roth, Updike, etc. Toole’s novel is so vexatious in its vast scope that we may be mystified, or, as Rabelais would humorously suggest, metagrobolized. Where Swift suggests a frame or standard in our powers of reason (in the famous letter to Pope, he redefines man from animal rationale to animal rationis capax), Toole, in exposing the American mania for political causes and “virtue signaling” (as we call it today), verges on discarding the frame or standard altogether. In his antics, Toole diminishes the middle-class realism that connects Swift to Defoe and turns, instead, to Rabelais, to Cervantes’ Don Quixote, to Shakespeare’s clowns and fools, and to Eliot’s Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.

The madmen, dreamers, and outcasts in this constellation are instruments of profound moral insight, the kind that cuts through seemingly inviolable conventions, including, say, the illusions of middle-class realism. Ignatius J. Reilly is a literary descendent of J. Alfred Prufrock (like Toole, Eliot was a transplanted Southerner), but Ignatius is adrift on a grander scale. As an oddball “celebrity,” he recalls Toole’s lost heroine, Marilyn Monroe, “who,” Toole wrote, “could find no bearings in the society which had formed her.” Toole’s nautical metaphors—the wheeled hot dog stand is often referred to as a ship—convey this sense of lost “bearings,” of a vessel that has gone hopelessly off course. In consequence, Toole’s moral defiance loses Swift’s indignant edge. To be sure, the moral hideousness of Lana Lee is plain to see, but hers is, relatively speaking, an underplot. Throughout Ignatius’ voyages into that hostile, Hobbesian state that Swift called “the Republick of Dogs,” Ignatius is always the center of attention.

The literary question that provoked this essay is: What does Toole’s comic genius mean to us? As the Victorian critic Walter Pater might suggest, how can comparison with Swift reveal Toole’s unique and special virtue? A good passage to consider, in this regard, is Ignatius’ recognition scene, one of the funniest payoffs in all literature, which occurs when his mother, Irene Reilly, returns his copy of The Consolation of Philosophy:

“Oh, my God! This has all been arranged,” Ignatius screamed, rattling the huge edition in his paws. “I see it all now. I told you long ago that that mongoloid Mancuso was our nemesis. Now he has struck his final blow. How innocent I was to lend him this book. How I’ve been duped.” He closed his bloodshot eyes and slobbered incoherently for a moment. “Taken in by a Third Reich strumpet hiding her depraved face behind my very own book, the very basis of my worldview. Oh, Mother, if only you knew how cruelly I’ve been tricked by a conspiracy of sub-humans. Ironically, the book of Fortuna is itself bad luck. Oh, Fortuna, you degenerate wanton!”

As a goddess of late antiquity, Fortuna does not lend herself to immanentizing the eschaton. She militates against the millenarian fantasies that, as Lionel Trilling tried to warn us in The Liberal Imagination, occupy the unreal, academic mind. Like the Knight of the Sorrowful Countenance, Ignatius does not make progress. He comes full circle as the punchline of fate: the scholar of Fortuna is now her stunned sacrifice. But he is, at least, self-conscious regarding his worldview and his predicament.

In Gulliver’s Travels, the opposition of genius and dunce rarely survives the strain of experience.

As Toole’s epigraph seems to have prophesied, the dunces closed their eyes to this great American anagnorisis. “It isn’t really about anything,” Simon and Schuster editor Robert Gottlieb informed the hopeful young author in December 1964. “The book could be improved and published. But it wouldn’t succeed; we could never say that it was anything.” The point was apparently lacking. It is perhaps doubtful whether Gottlieb made the association between Ignatius Reilly and Saint Ignatius of Loyola—I shall return to this concern.

Swift reminds us that literary justice can be severe. The ugly likelihood, it must be acknowledged, is that Gottlieb recognized, on some level, that his own culture was being skewered. When “a young Female Yahoo standing behind a Bank” is “enflamed by Desire,” the human race receives a slap in the face. It may seem an unfair blow, directed at a defenseless female, but it has stood the test of time. In Gottlieb’s judgment, Myrna Minkoff is “a pain in the ass.” Myrna is a sexually enflamed, post-religious Freudian Jew whose conscience has splintered into a thousand progressive causes. In response to his editorial predicament, Gottlieb turned for guidance to the ethnically conspicuous “Candida Donadio, a young woman who is probably the best literary agent in town (one of my closest friends).” Ain’t that nice, Ignatius? Gottlieb has a friend who’s a Catholic! In the end, after his two-year ordeal, when Toole is finished apologizing, suffering, revising, and diminishing himself, all that remains is the original manuscript in its shoebox, and Manhattan’s normative skyscrapers. Small surprise the New Yorker eventually made Gottlieb editor.

The Swiftian Touch

“The prime significance of Swift’s sin of wit,” Geoffrey Hill observes, “is that it challenges and reverses … the world’s routine of power and … considers all alternatives including anarchy.” Likewise, the prime significance of Toole’s anarchic sin of wit is that it challenges and reverses the philistine norms of political orthodoxy and social control that have ravaged American intellectual life like a cancer. Michiko Kakutani, a more recent enforcer of New York’s cultural authority, prefers Toole’s morally simplistic juvenilia, The Neon Bible, to his magnum opus. Another writer at the New York Times, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, fell to mocking the “myth” of Toole’s “lonely genius” and doubting that the book merited a Pulitzer. Early in 2021, Tom Bissell made sure the beat went on, a beat more militant than musical, publishing “The Uneasy Afterlife of ‘A Confederacy of Dunces,’” an essay so antiseptically, self-consciously, and provincially New Yorker, it felt like a bespoke suit tailored for a man allergic to cloth. It is notable that none of these critics notices the depth of Toole’s erudition. Because to discuss Toole’s relation to Swift would be to elevate Toole’s stature, this line of critics is not interested.

The sense of protesting too much haunts these proceedings. Self-justification has eclipsed literary justice. Toole’s death is a kind of landmark, an unwanted war memorial. I will say it: if you want to understand American culture, then you must confront the reality of Toole’s suicide at the age of 31. One must understand, as well, that, beyond the maternal persistence of Thelma Toole (who kept at it through numerous rejections), beyond the heroic generosity of Walker Percy, it was the reading public that saved A Confederacy of Dunces; we owe the immortality of Gulliver’s Travels to the same mortal tribe.

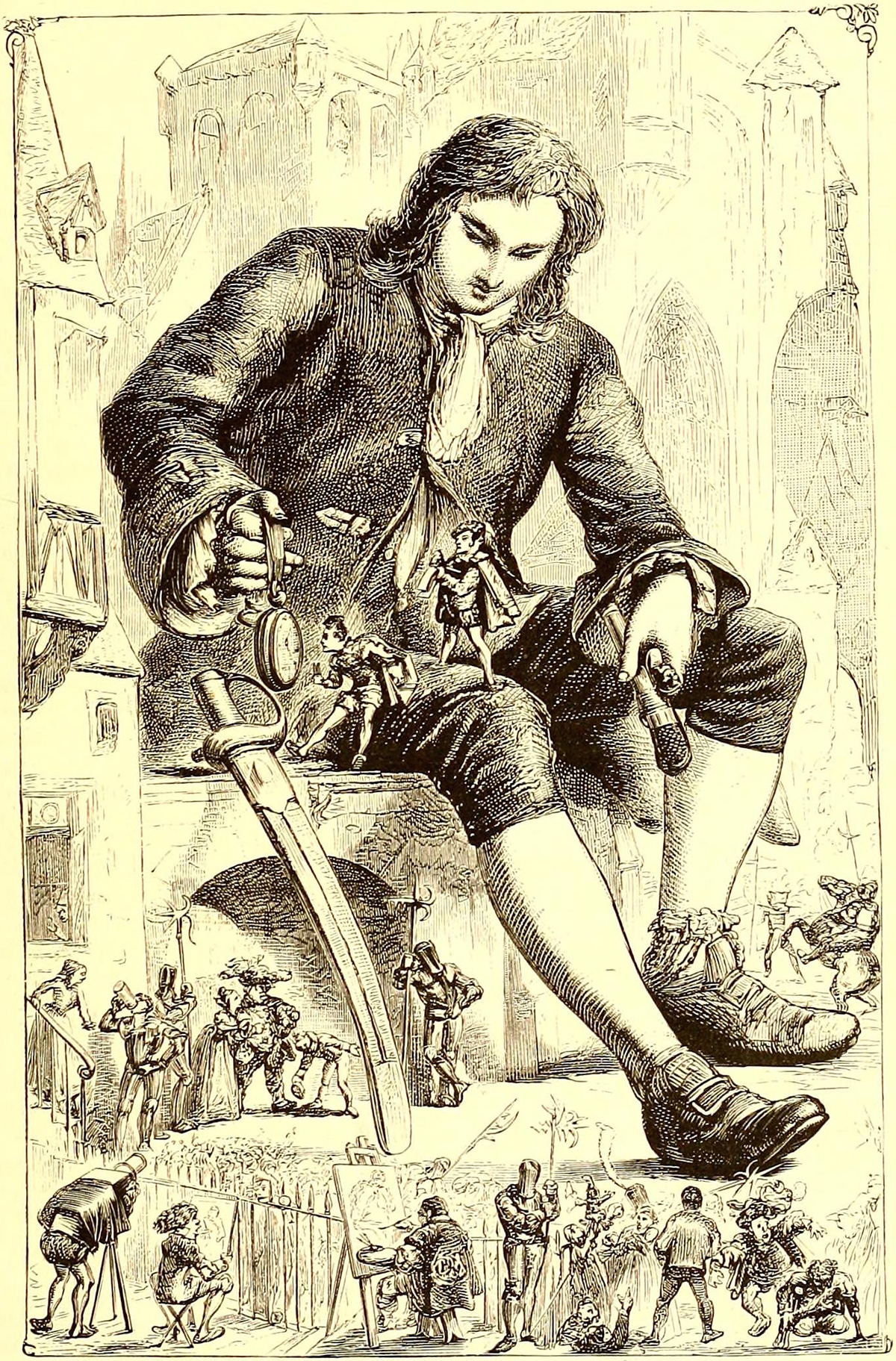

Gulliver’s “Travels into Several Remote Nations” are adapted, in Toole’s New Orleans, to Ignatius’ colossal and Lilliputian state of alienation. The Reilly house in New Orleans is “a Lilliput of the Eighties,” where the elephantine Ignatius resides with his “huge feet.” Mr. Levy, the reluctant owner of a Levy Pants and husband to the fiercest shrew in American literature, asks in a moment of sympathy (despite the damage done to him by Ignatius), “Could the huge kook live in such a dollhouse?” Technicolor visions at the Prytania movie theater compare to a tiny Gulliver’s observing the Maids of Honor in Brobdingnag: “She smiled in a huge close-up. Ignatius inspected her teeth for cavities and fillings. She extended a leg. Ignatius rapidly surveyed its contours for structural defects.” Miss Trixie, the octogenarian assistant accountant, is Toole’s version of the immortal Struldbrugs. The mock Eucharist at the Academy of Lagado is a precursor to Lana Lee’s mock Eucharist in the Night of Joy. The Battle of the Books, the culture war of Ancients versus Moderns, is restaged as the battle of Boethius and Hrosvitha versus television and Lana Lee, in whose pornography, which is intended for teenage consumption, the final logic of the cash nexus stands revealed.

In A Tale of a Tub: Written for the Universal Improvement of Mankind, Swift mischievously includes a Rabelaisian list of treatises “which will speedily be published.” These include A Panegyrical Essay upon the Number THREE,Lectures upon a Dissection of Human Nature, and A general History of Ears. The Tale is written in the persona of an anonymous Grub Street hack. Its target is the mind of the age. That mind and the hack’s mind are, if you can gain the perspective, very close of kin. Ignatius’ Journal of a Working Boy is likewise the work of a conceited and brilliant hack, a “sociological fantasy” loaded with digressions that realize and instantiate the “failure to make contact with reality.” Such failure is Ignatius’ chief criticism of our age, and his own failure to make contact with reality does not invalidate his criticism. We find that both authors, Swift and Toole, are carnival maskers, writing in persona to revel in the sin of wit.

Paradise Lost

Utopian schemes abound in both authors. Tracing the transformations of matter into spirit, both dwell on the biology behind our ideals and aspirations. The “Wise Aeolists,” the hack writes, “affirm the Gift of BELCHING, to be the noblest act of a Rational Creature.” It is a noble act that Ignatius cultivates in the high tradition. When Swift, with a schoolboy wink, has Gulliver refer to the death of “my good Master Bates,” the author is clowning around but also alerting the attentive reader that Gulliver is Gulliver (cf. gullible) and therefore not to be entirely trusted. The bed sheet on which Ignatius scrawls Crusade for Moorish Dignity bears the yellow stains of his onanistic “hobby,” the source of “flights of fancy and invention.” When Toole describes Ignatius exercising his rubber glove, he is satirizing Ignatius’ “Rich Inner Life” by exposing its fons et origo. As for the female of the species, her saving this strange soul is one of Myrna’s “most important projects.” Her public lecture in New York is conducted in the spirit of the Aeolists’ female priests, “whose Organs were understood to be better disposed for the Admission of those Oracular Gusts, as entering and passing up thro’ a Receptacle of greater capacity, and causing also a Pruriency by the Way.” Despite Toole’s reliance on Swift and Freud, the author of A Confederacy of Dunces manages somehow to retain a romantic affection for human sexuality. Ignatius is polymorphously perverse, and Toole presents sex in any terms as an expression of human folly. And yet it brings lonely individuals together (unlike Lana Lee’s pornography), and it makes Myrna and Ignatius a pair. The scene where Irene Reilly and Claude Robichaux join hands has a pathos unique in literature: it possesses a special virtue, something akin to Act V of Midsummer Night’s Dream but romantically serious and dignified in a working-class milieu unknown to Shakespeare’s stage.

Swift, by contrast, scours all Edenic traces from the earth. Eden is irretrievably lost, and his salvos against the utopian visions of science underscore this point—in fact, C.S. Lewis saw Laputa as an “attack” on science itself. Let us accompany Gulliver to Lagado, the residence of impoverished scientists:

The Projector of this Cell was the most Ancient Student of the Academy. His Face and Beard were of pale Yellow; His Hands and Cloths dawbed over with Filth. When I was presented to him, he gave me a very close Embrace, a Compliment I could well have excused. His Employment from his first coming into the Academy was an Operation to reduce human Excrement to its original Food, by separating the several Parts, removing the Tincture which it receives from the Gall, making the Odour exhale, and scumming off the Saliva. He had a weekly Allowance from the Society of a Vessel filled with Human Ordure, about the bigness of a Bristol Barrel.

This particular Projector is recognizable as a latter-day alchemist, and Gulliver notes that “none of these Projects are yet brought to Perfection.” But Swift is surely within his rights as a satirist to mock them (much as Erasmus satirized bad theology) without our leaping to the conclusion that he was anti-science tout court.

Ignatius and Myrna are both modern-day Projectors, and the ironical sound of project echoes through Toole’s novel to form a leitmotif. At the same time, Toole’s departure from Swift’s excremental vision correlates to a lack of savage indignation on Toole’s part. Folly and humanity are so inextricably bound that no moral intelligence can unravel them. Morally, the enemy for Toole is not folly, irrationality, or social vanity, since they are all inevitable and often incite us to laughter, but the “negation of all human qualities.” This is what Ignatius astutely recognizes in Lana Lee, the character most lacking in human sympathy—though Ignatius himself is far from being a model of sympathetic feeling. Her powers of reason, in its instrumental mode, are strong, but cold pride undoes her because she is overly confident that she can spot an undercover cop. Her arresting officer, Patrolman Mancuso, is honest but incompetent. His sergeant gives him the business. “Mongoloid Mancuso” (as Ignatius calls him) does not succeed at last by virtue of his merits. He is not a middle-class success story living the American dream. Lana gets what she deserves, and Fortuna is simply kind to him, at long last.

Gulliver’s Travels shows an abiding concern for both the meaning of the word Christian and the moral obligations that a Christian conscience entails.

Swift, in his growing concern for the poor in Ireland, remains a realist. Toole’s portrait of working-class New Orleans has the angular realism of great caricature. It is closer in this respect to Marlowe, Jonson, and Rabelais than to Swift: it is not out to reform the school of hard knocks and its cast of suffering humanity. “Life’s hard” is the choric plea of Irene Reilly. Santa Battaglia remembers her own mother: “It was hard in them days, Irene. Things was tough, kid.” But Swift, compared to Toole, is more severely impersonal. Denis Donoghue comments on Gulliver’s Travels: “Gulliver is not, strictly speaking, a character at all. He is someone to whom things happen.” Ignatius, by contrast, establishes a powerful sense of self and an independent imagination, however adrift and incongruous. He remains the glorious, personal center of the action, even if he is also “someone to whom things happen.” His grotesquerie fits with his tragic-comic nature, which is the source of our sympathy for him, as opposed to Gulliver, who, like the Robinson Crusoe of Virginia Woolf’s alert criticism, “has a way of snubbing our enthusiasms.”

Another, Very Different St. Ignatius

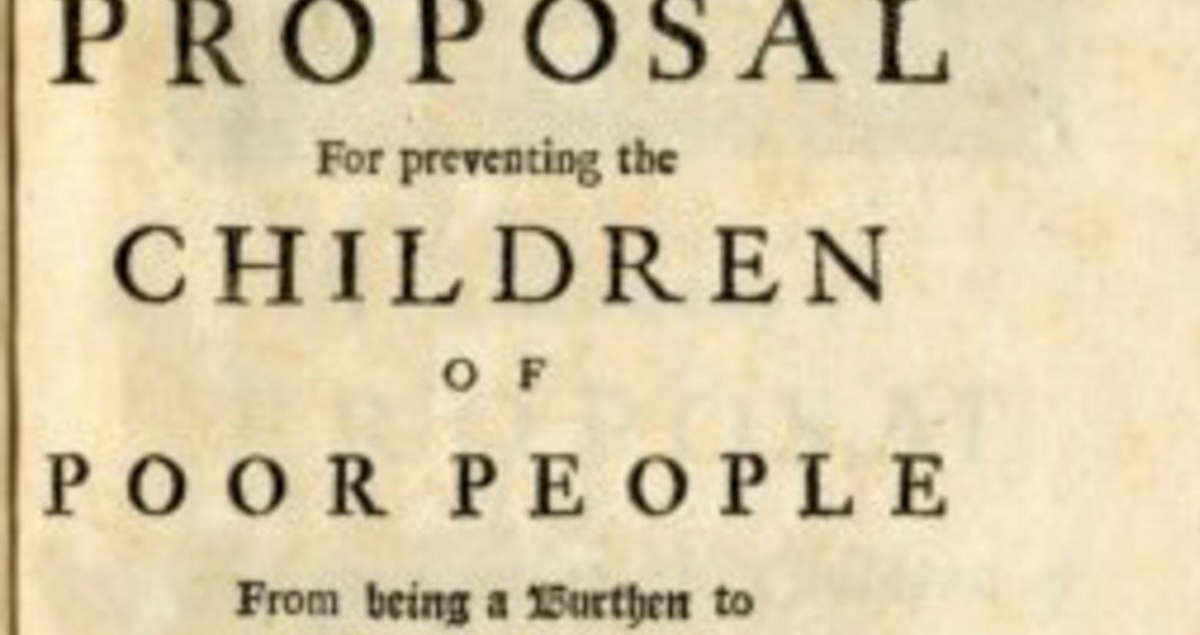

In their different approaches to character, we glimpse the tribal and religious affiliations that separate the two authors. Swift is an Irish Protestant; Toole an American Roman Catholic of strongly marked Irish descent (his Creole ancestry lends a romantic backdrop to the potato famine lineage). When Swift was given the Deanery of Saint Patrick’s in Dublin in 1713, he saw it as a defeat, long having coveted a position in England. Ireland was exile. But in the years after the death of the “royal prude,” Queen Anne, in 1714, with the fall of the Tory ministry and the rise of the Whigs under Sir Robert Walpole, Swift more than fulfilled his administrative and priestly duties as a high-ranking official of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy. Over time, he became the Drapier Dean, the author of A Modest Proposal (1729), patriotic champion of a conquered people for whom he felt little affinity but whose suffering roused his Christian conscience.

While Toole’s childhood was neither poor nor culturally famished, his Irish heritage was summed up by his mother, Thelma Toole, when she remarked in 1981 to TV host Tom Snyder, “Someone told me that in Ireland perception extends to the working classes!” The “someone” in question may have been her son, the young professor who in 1961 wrote on his blackboard at Hunter College, “Anticatholicism is the antisemitism of the liberal” (sic). “The WASPS were routed,” he wrote his friend Joel Fletcher in February 1961, in the wake of JFK’s victory over Richard Nixon. Tribalism is intrinsic to his work, because it animates his self-consciousness. But it is not a matter of provinciality: it is a particular tribalism with a universal message, such as we find in the Harlem Renaissance.

Ignatius J. Reilly presents the strangest vision of the Church militant that the world has ever seen.

Swift was obviously a serious Christian. Gulliver’s Travels shows an abiding concern for both the meaning of the word Christian and the moral obligations that a Christian conscience entails. He confronts the limitations of deism and the corruptions of the Church. But Swift belongs to that period in English literature when England was recovering from the religious enthusiasm of the Civil War. He has read Hobbes, who described imagination as “nothing but decaying sense.” He takes a good deal from Locke, whose materialist psychology informs The Mechanical Operation of the Spirit (1704), a satire on religious enthusiasm. He despised spiritual and stylistic pretension, and in this respect his religious and literary outlook were unified.

But where Swift satirizes spiritual enthusiasm to exterminate it, Toole transforms spiritual enthusiasm into what I am tempted to call “pyloric” enthusiasm, fueling a kind of endless carnival masque or Mardi Gras. Swift is the administrator. He prefers an efficient style (when he isn’t adopting a persona or mask), an efficient nation, and an efficient Church. He wants to set things to rights and make them work. Sergeant Toole was himself an administrator—at a U.S. Army outpost in Puerto Rico called Fort Buchanan, where he ran the English-language program for undereducated recruits. Tribally, though, Toole was never in power. He had very little faith in modern administrative or bureaucratic solutions. Swift had no great faith in government but he had a country to care for. Toole was beyond all that. Ignatius is incapable of improving anything. He identifies with impoverished African Americans, except when they voice middle-class aspirations. His native Roman Catholicism is active only in prayers to obscure saints. It cannot be modernized, despite Vatican II. It cannot be progressive.

And yet, Toole is never misanthropic. His comedy concludes on a note of gratitude, a curious note of self-penetrating grace as Ignatius makes his miraculous escape:

He stared gratefully at the back of Myrna’s head, at the pigtail that swung innocently at his knee. Gratefully. How ironic, Ignatius thought. Taking the pigtail in one of his paws, he pressed it warmly to his wet moustache.

“The book could be improved and published. But it wouldn’t succeed; we could never say that it was anything.” Then again, the repetition of “gratefully” is striking—coming after Ignatius has been entombed alive in the prison of himself and declared mad by society. As I have suggested, the key reference may have been lost: “Ignatius,” as described by Toole’s friend Emilie Russ Dietrich (later Emilie Griffin), “a kind of latter-day Loyola at odds with sinful society.” We may further note, with Toole biographer Cory McLauchlin, that Toole was “baptized in the Catholic Church at Loyola University.”

Ideally (ironic adverb!), Ignatian spirituality leads to a synthesis of prayer and action, to the formation of active contemplatives. Ignatius J. Reilly is the alienated, dark-horse inheritor of this tradition, teetering on the “very rim of our age.” He presents the strangest vision of the Church militant that the world has ever seen:

My cutlass slapping against my side, my earring dangling from my lobe, my red scarf shining in the sun brightly enough to attract a bull, I strode resolutely across town, thankful that I was alive, armoring myself against the horrors that awaited me in the Quarter. Many a loud prayer rose from my chaste pink lips, some of thanks, some of supplication. I prayed to St. Mathurin, who is invoked for epilepsy and madness, to aid Mr. Clyde (Mathurin is, incidentally, also the patron saint of clowns). For myself, I sent a humble greeting to St. Medericus, the Hermit, who is invoked against intestinal disorders.

Rest assured these are real saints. Mathurin, also called Maturinus, was ordained by St. Polycarp in the fourth century. Medericus, also called Merry, is a seventh-century figure associated with St. Martin’s monastery in Autun, France. Ignatius thus emerges as an absurd St. Ignatius, a parody, if you will, but a parody with heart and soul.

Returning to Swift, we can now see the difference between the two authors at its most absolute. Gulliver, with his solid vocational training, never joins prayer and action. After his final voyage, he is terribly cut off from grace. His reasoning leads him to recognize his abject insignificance. Swift ends his greatest work in negation: “and therefore I entreat those who have any Tincture of this absurd Vice [of Pride], that they will not presume to come in my Sight.” By contrast, Toole’s closing movement is sympathetic. He uses his extraordinary skill at plotting to give things a providential twist, concluding in a weird Edenic plenitude: “Taking the pigtail in one of his paws, he pressed it warmly to his wet moustache.” If I imagine someone reading Toole’s valedictory passage at his funeral, the word that seems to stick out is innocently. Ignatius and Myrna retain a saving vestige of their innocence. Our better angels must extend a similar grace to that dignified man, Robert Gottlieb, and even to those who have, as it were, gleefully danced on Toole’s grave. We are all fools gone wrong, all in need of forgiveness, and possibly that is the point of the novel after all.