The landmark 1983 study of American education, titled “A Nation at Risk,” warned that “the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people.” It continued: “If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war,” a claim one critic of the report suggested “came perilously close to defining teachers and administrators as enemies of the United States.” Whatever the reliability of the data, the overall thrust of the findings seemed largely correct, but the proposed correctives would receive an F. America’s schools have not improved.

The education reformer believed a good education meant freedom from authority, curriculum, and convention. And especially parents. We’re seeing the fruit of this approach today.

The report’s recommendations failed in no small part because the authors did not provide a sound analysis of how things had gotten to such a state. Nor did it ask the question of central importance: Were the problems the schools faced a bug or a feature of the design of the system? And if the latter, who were the designers and where did they go wrong?

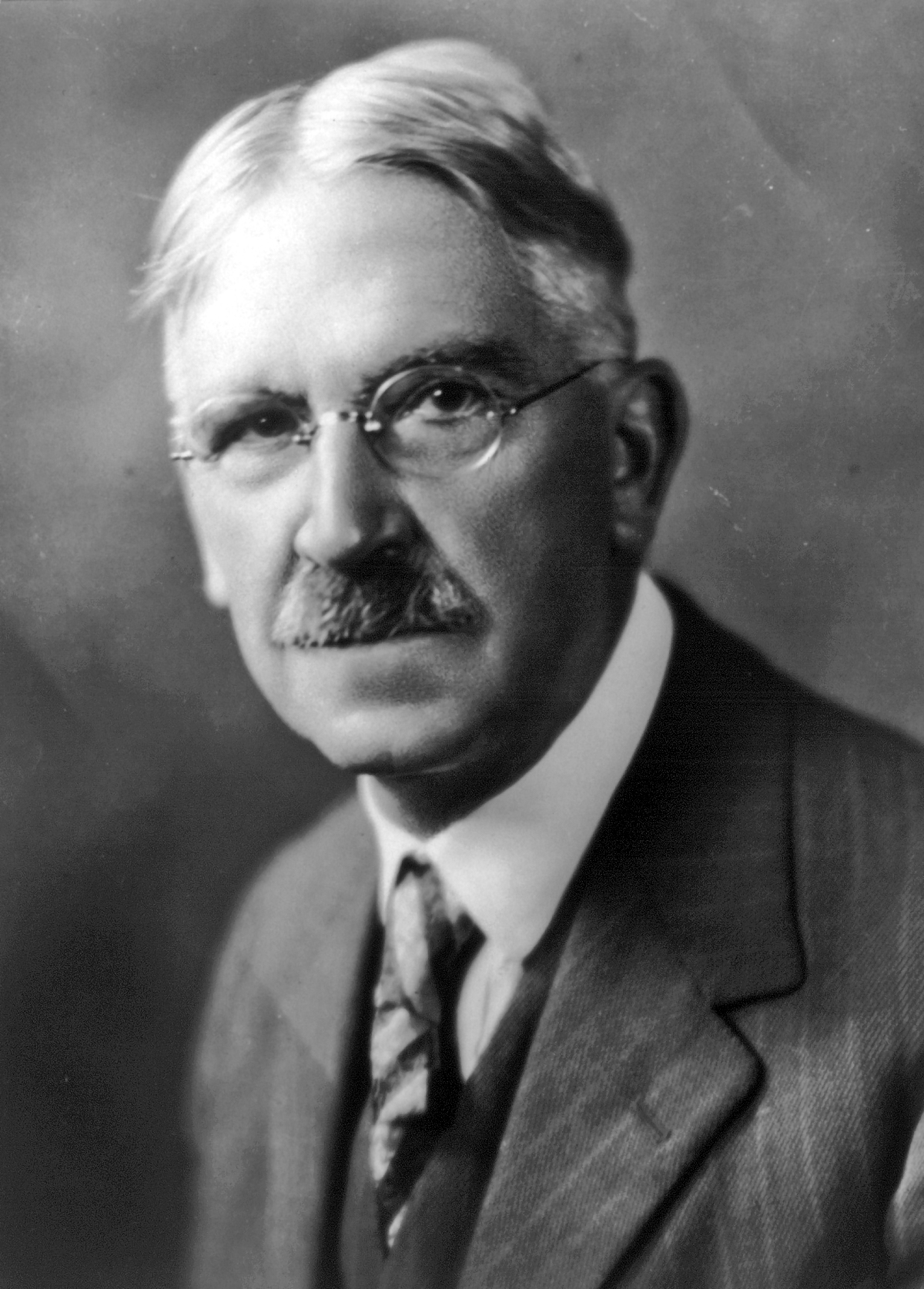

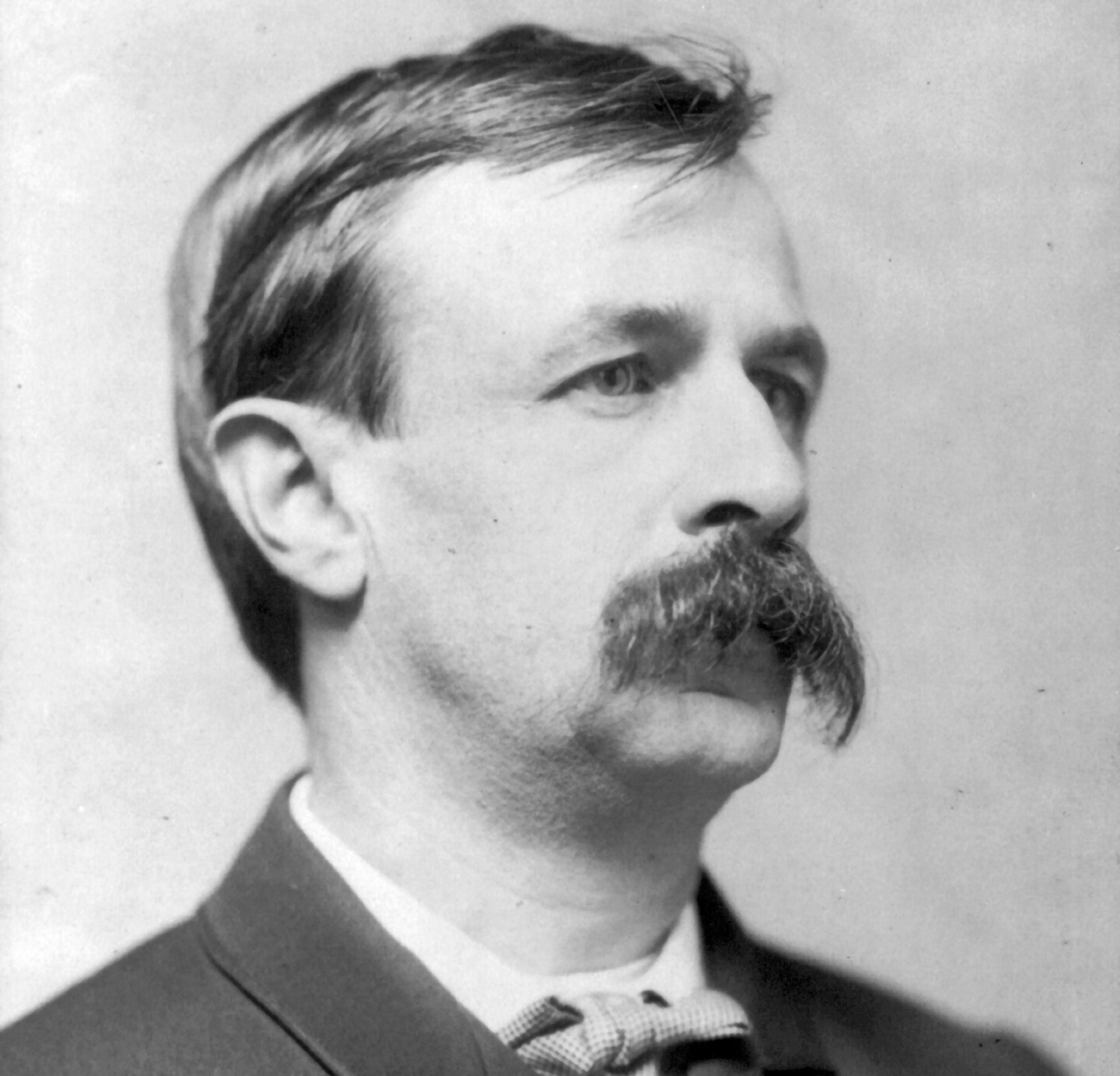

Most social institutions don’t have “designers”; they’re the result of generations of trial and error. This does not mean, however, that extant institutions cannot be suddenly altered by those convinced they have found the status quo wanting and, within themselves, the unquestioned principles of reform. In the case of America’s schools, the great transitional period was the later 1800s and early 1900s, and the main reformer was John Dewey.

Independent of the decimal system that bears his name, many Americans have heard of him, and almost all Americans have experienced in some fashion the consequences of his ideas. The scope of his influence tends to result from assigning him too much credit or blame for our current state of affairs. Defenders of Dewey may still insist that his ideas were sound but never fully realized, while critics will credit those ideas for destroying our schools.

Conservatives have long been critics of Dewey’s reforms. Flannery O’Connor and Russell Kirk’s one interaction with each other involved both expressing gratitude that Dewey and his acolyte William Heard Kilpatrick had recently died. Kirk blamed Dewey’s Democracy and Education for some of the deficiencies in his own education, while O’Connor advised parents to “beat your children moderately and often; and anything that Wm. Heard Kilpatrick and Jhn. Dewey say do, don’t do.” Dewey himself observed that “I seem to be unstable, chameleon-like, yielding one after another to many diverse and even incompatible influences; struggling to assimilate something from each and yet striving to carry it forward.” This quality of not being able to pin him down, of his contradicting himself, of the sheer vagueness or unintelligibility of his language, combined with the vast volume of what he wrote, strains the ability of any interpreter. Hannah Arendt wrote about Dewey’s writings that “it is equally hard to agree and to disagree with it,” and Oliver Wendell Holmes observed that Dewey was what one would read if one wanted to know what God thought if God was incapable of expressing Himself clearly.

Dewey is one of those rare figures whose influence is impossible to over- and understate. Given the central importance of schooling, this would be the fate of any person responsible for large-scale changes. But we might also suspect that a good part of the reason we misunderstand his legacy is that many people study Dewey’s ideas without actually studying Dewey’s writings.

For this one can hardly be blamed. Dewey wrote both voluminously and clumsily. He never put a premium on precision, clarity, and consistency of thought; or, if he did, he never accomplished these things. Even native speakers find his writings hard to decipher, both for the turgidity of expression and the often-contradictory web of ideas. He borrowed liberally from other thinkers, which at times makes his original contributions difficult to discern. His influence as a thinker, however limited, results from the central insight that all thought must resolve itself into action.

Democracy and the Kingdom of God

Dewey was born in 1859, the same year as the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, and Karl Marx’s A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, which would become the groundwork for his subsequent Das Kapital. These three books significantly influenced Dewey: on the positive side from Darwin and Marx, and on the (mainly) negative side from Mill. All three works put individual existence into relief against larger historical and cultural forces, and all three suggested that the past and tradition not only offered no sure guide for action but were to be discarded remnants of a now gone and discredited world. Life needed to be recast on an entirely new basis, a new mode of understanding. While Mill focused on cultural and intellectual forces, Darwin and Marx both inclined to see the social world as an epiphenomenon of fundamental material forces. Even though Darwin was the biggest influence on Dewey, Mill’s articulation of liberalism and Marx’s critique of industrial capitalism both played a large role in setting the parameters of his work.

The Origin of Species, like many of Dewey’s own books, is mostly unread but has exerted enormous cultural influence. And, like many thinkers, Dewey experienced that book as a paradigm reset: it put faith and science in conflict with each other, to the disadvantage of the former; it stressed that development occurs only in interaction with the surrounding environment; and it seemed to stipulate that this development was melioristic. While Dewey cannot be accused of being a social Darwinist, mostly because his egalitarian impulses wouldn’t allow it, he did believe that the interaction between persons and their environments would result in the betterment of the species. The key would be to control and manipulate the environment, and obviously the earlier in a member’s life you can control that environment, the greater the benefit that would redound to the species as a whole.

Given the importance of interaction between species and environment, Dewey naturally became concerned with the preeminent social environment of his day—namely, industrial capitalism. He may not have shared Marx’s determinism, but he did share his concerns about economic inequality. In Dewey’s rendering, the “socialized intelligence” in the controlled environment of the schools (for the art of teaching was not referring to a subject matter but managing the environment) would make “the abuses and failures of democracy [and any vestiges of plutocracy] … disappear.”

Like Darwin with biology and Marx with economics, Dewey approached both democratic and educational theories as if they were science. The common impulse may in part account for why, when he visited the Soviet Union in 1928, Dewey and his ideas were greeted enthusiastically. But in his hands the idea of science took on a decidedly moral sheen, for he argued that science could solve the fundamental problems attendant to human nature, and thus bring about endless moral progress. For Dewey, the advancement of science and democracy went hand in hand, in no small part because the procedures of science mirrored those of democracy.

In many ways, however, the central figure in Dewey’s development was the German philosopher Georg W.F. Hegel, who argued that historical progress occurred when opposites were reconciled into a higher synthesis. Perhaps the most brilliant synthesis in Hegel’s work was to balance the claims that all knowing was historically and culturally conditioned with the belief that, nonetheless, absolute knowing was achievable. The key was stipulating that knowledge conditioned by the end point of history, what in Christian theology might be thought of as the Kingdom of God, was a kind of relativism one could live with. While Dewey did not share Hegel’s yearning for absolute knowledge, he did retain the identification of the Kingdom of God with his own historical moment.

Having been raised in a Puritan New England household with a religiously strident mother, Dewey rejected faith in 1891 and stopped going to church in 1894, claiming that religion was little more than “intolerance and fanaticism.” But the residuals of Christian faith remained with him, partly in the claim that sectarian churches would collapse into a secular democracy. Dewey may be credited for mainstreaming Hegel’s ideas into American political thinking. Dewey himself admitted that his encounter with Hegel had “left a permanent deposit in my thinking.”

Progress required the negation of tradition, of prior ways of thinking, living, and believing.

Dewey enthusiastically took up Hegel’s challenge that the modern world uniquely combined a new science with a form of social organization that could synthesize the moral unity of the ancient world to the individuality of the modern world. Moral progress was contingent on cultural progress, which in turn required the sheltering and coordinating power of the modern state—“the March of God through time.” Democracy, in its continual unfolding, became for Dewey the realization of the Kingdom of God here on earth. But such progress required the negation of tradition, of prior ways of thinking, living, and believing. The past was no longer a heritage to be passed along but an obstacle to be overcome. Politics and law—and especially education—had to become dedicated to such overcoming.

But how to catechize democratic citizens, with their chaotic willfulness and nettlesome individuality, into a secularized kingdom wherein alone they could find their true freedom? The obvious answer was state-mandated and -controlled educational apparatuses. Dewey was long enamored of 19th-century America’s greatest effort at socialist catechesis: Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, which Dewey ranked only behind Das Kapital as the most important book of the previous century. In April of 1934, as the Great Depression descended on America, Dewey wrote an appreciation for Bellamy’s bloodless revolution, where human activity was directed toward a common good and all wealth was held in common. Dewey saw Bellamy as the great defender and prophet of American democracy. Perhaps the most important educational idea that Dewey got from Bellamy was that the traditional systems of education were predicated on and perpetuated an unjust class system. Dewey, like Bellamy, vehemently opposed any vestiges of hierarchy and old class structures in education. The democratic purpose was to facilitate communication and to involve everyone in a great society founded on mutual sharing and responsibility, while also identifying the tasks for which each person was uniquely fitted.

Schools as Tools of the State

The idea of progress as the central organizing principle of social life is the key idea of the 19th century. Given the tremendous acceleration of the rate of social change, reformers were inclined to see progress as leading to perfection in the here and now. Dewey connected the schools to this central philosophical or quasi-religious belief. Dewey claimed America was the historical bearer of a special truth, and that there are no deep truths. What made Americans so special in this regard was their ability to live comfortably with this knowledge. What gave them comfort was a faith in progress as a secular process. Like his later disciple Herbert Croly, Dewey believed that America existed more as Promise than as Fact, and the reforming of social institutions was required to achieve that promise, with the schools being the most important institution to reform. The key to reform was dismantling the curriculum and putting the interests of the student at the center.

Students should be told as little as possible and enabled to discover as much as possible.

To accomplish this, students should be told as little as possible and enabled to discover as much as possible. “The child’s own instincts and powers furnish the material and give the starting point for all education,” the central purpose of which is to adjust individual activity to the needs of society. The schools must be transformed into tools of the state dedicated to the purpose of reforming society along the lines of progress. This adapting of human power to social purposes is “the supreme art” that brings an end to all want, social division, and violence—not just in theory, but in actual practice. Thus the schools take on utopian tasks that require no limits to the “resources of time, attention, and money which will be put at the dispense of the educators.” And why would that be? Because “the teacher always is the prophet of the true God and the usherer in of the true Kingdom of God.”

Dewey saw the purpose of education as liberating the student from the past toward full membership in a democratic community, thus “letting the child’s nature fulfill its own destiny.” Education in a democracy “repudiates any principle of external authority” and rejects any understanding of the past except as it meets present needs. “The segregation which kills the vitality of history is divorce from present modes and concerns of social life. The past just as past is no longer our affair. If it were wholly gone and done with, there would be only one reasonable attitude toward it. Let the dead bury their dead. But knowledge of the past is the key to understanding the present. History deals with the past, but this past is the history of the present.” This freedom from the past tracked well with “the great advantage of immaturity,” which is that “it enables us to emancipate the young from the need of dwelling in an outgrown past.” He believed that “the business of education is rather to liberate the young from reviving and retraversing the past than to lead them to a recapitulation of it.”

This rejection of tradition reflected Dewey’s central concern that education should meet social needs and solve social problems. The mechanism for ensuring such is his notion of growth. Many commentators have observed how nebulous and frustratingly unclear Dewey’s notion of growth is, one simply referring to it as a “mischievous metaphor.” Like Darwin, Dewey saw growth both as a process without an end and resulting from the interactions of any organism with its environment. It is constant forward movement, intrinsically related to the progressive creed that “it is better to travel than to arrive, it is because traveling is a constant arriving, while arrival that precludes further traveling is most easily attained by going to sleep or dying.” Probably the closest he comes to defining it is when he wrote, “This cumulative movement of action toward a later result is what is meant by growth.”

But that’s a fairly vapid definition and one that results from his rejection of all a prioris or any appreciation for tradition. Most of us will distinguish between good growth (muscle) and bad growth (fat), but that requires that we have some sort of criteria we can apply, and Dewey is adamant in rejecting any absolute or transhistorical criteria. Relatedly, his disciple Richard Rorty observed that there is nothing in or about human beings that would transcend the truth of the historical moment, so if the secret police knock on our door, there aren’t any external criteria to which we might appeal to resist them other than to suggest, weakly, that we ought not be cruel. If National Socialism is the truth of our day, Rorty wrote, then so much the worse for us. But most of us would be inclined to take up the question at that point and ask why it’s worse, but this gets us into the realm of philosophy. For Dewey and Rorty, philosophy is merely a description of how people actually live and offers no normative criteria.

Furthermore, the “movement of action to a later result” tells us nothing about the desirability of that result. A man might enter a bar, talk to the woman sitting next to him, buy her a drink and then another, and eventually commit adultery with her, and each action is understood in terms of its relation to a later result, but many might find this all morally condemnatory. In other words, we would want to be able to distinguish between good and bad results by employing criteria that are not themselves part of the process, and to that Dewey is stridently opposed. Dewey never really had a plan to replace what he discarded, which must inevitably happen when you jettison respect for the past in favor of endless futurity. For the past can be known; but the future, since it does not yet exist, cannot be known except by faith—this “democratic faith” being the crux of Dewey’s thinking. Allow democracy its rein, discipline it with a system of education, and the result is “the great community.” And, like many progressives who dreamed of a great community, the greatest barrier was any principle of division.

The schools take on utopian tasks that require no limits to the ‘resources of time, attention, and money.’

This aversion to division accounts for his attitude toward the states and local governments as centers of education, to churches as sectarian enterprises, and to families as independent entities, the idiosyncrasies of which required undoing by mandatory, universal, state-run schools.

The school has the function also of coordinating within the disposition of each individual the diverse influences of the various social environments into which he enters. One code prevails in the family; another, on the street; a third, in the workshop or store; a fourth, in the religious association. As a person passes from one of the environments to another, he is subjected to antagonistic pulls, and is in danger of being split into a being having different standards of judgment and emotion for different occasions. This danger imposes upon the school a steadying and integrating office.

The schools, to repeat, are microcosms of the desired community. Because modern societies are irrational and inefficient, the schools must become rational and efficient. They must be purged of all the problems that plague society, and this results from Dewey’s belief that human nature can be perfected if it is placed in the right environment. Currently extant environments were clearly not doing their job, and so students had to be emancipated from them. They had to be “gradually weaned from their homes” and the emotional ties that connected them to their parents in favor of “an impersonal intellectual and social diet.” This symbiotic process of liberating the child from home and church would result in the child being the instrument that would liberate society from its past. Traditional society has spoiled the “plasticity” of the child and his or her “power to change prevailing custom” by having mastered “the art of taking advantage of the young” by substituting static adult interests for dynamic juvenile ones. A healthy society does not transmit its achievements to the young but allows them to shape a vision of the future.

Dewey believed that the liberal arts simply reflected the interests of a corrupt ownership class who used the schools to perpetuate its own interests.

Dewey opposed the liberal arts, which are relics of a feudal past, in favor of the liberating arts, those which prepare students for life in the great community. A good education is liberating in that it is “freedom from authority, freedom from the curriculum, and freedom from convention.” Dewey believed that the liberal arts simply reflected the interests of a corrupt ownership class who used the schools to perpetuate its own interests. The schools, as they existed at Dewey’s time, celebrated the leisure of the liberal arts, that is, an education that had no purpose beyond itself, but had “their origin in the fact that the reflective or theoretical class of men elaborated a large stock of ideas” that maintained an unequal society. And in that present moment, “Our economic conditions still relegate many men to a servile status. As a consequence, the intelligence of those in control of the practical situation is not liberal.”

The Irony of a “Classless” Education

Many current ideas are part of Dewey’s legacy, but one of them is the idea that a classless or nonhierarchical society is an inclusive society. Clearly the schools have become the major drivers of the push for inclusion. Nor ought we lightly to dismiss the impulse. Dewey may have started the idea, but it picked up steam in the 1990s with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the creation of classrooms that could serve the needs of students who traditionally, because of either physical or mental handicaps, could not succeed in the schools. Undoubtedly the parent of such a child might have some positive things to say about inclusion. But the term is not self-justifying, nor is it fully coherent. As in any egalitarian enterprise, Dewey’s schools tend to have a leveling effect. His classrooms are not friendly places for bookish or introverted students. Instead, schools require that “methods of instruction and administration be modified to secure direct and continuous occupation with things” in opposition to the traditional schools that “substitute a bookish, pseudo-intellectual spirit for a social spirit.” His focus on external action negated the importance of contemplation, especially as regards to what it meant to live a good life. Dewey believed that the virtues were nothing more than “working adaptations of personal capacities with environing forces.” As a result, he wanted schooling to have nothing to do with character formation, since that would predicate itself on normative (adult) modes of conduct; instead, schools should focus on citizen formation.

Dewey had already set up a laboratory at the University of Chicago to test his educational theories, and then later help set up the nation’s first school of education. One of the problems with these schools of education, whether free-standing or embedded in a university, is that people who study there are not required to master a subject matter. Dewey insisted that the job of the teacher is not to communicate a subject matter but to produce the right kind of learning environment, one where the interests and desires of the student determine the educational project. As a result, schools of education tend to be populated by people who don’t know a whole lot but are coached in techniques of management. (I will testify to that—on the whole, education majors were my worst students.)

What’s worse, even though Dewey insisted that the interests of the student be dispositive in establishing the practices and procedures of the school, he could not avoid the fact that teachers have to teach something, and this opened the door for teachers to engage in ideological promulgation. Indeed, schools of education have been described as “menaces” to the whole educational enterprise because of their tendency to indoctrinate students into a progressive ideology. In no small part this results from their “stand-alone” status and the fact that they can always hide behind certification agencies, which themselves are typically ideological. The stand-alone status of these schools means that the professors who work there are able to work outside the dialogue with and scrutiny of other university scholars, many of whom would blow the whistle on the shabby scholarship that takes place.

Again, the belief that the interests and desires of the student determine the educational enterprise is the linchpin of Dewey’s theories. “It is as absurd,” he wrote about parents and teachers, “to set up their ‘own’ aims as the proper objects for the growth of children as it would be for the farmer to set up an ideal of farming, irrespective of conditions.” Granted, the teacher had a role to play in directing the child’s impulses, but Dewey gave no guidance for how or when, other than asserting that it all had to be directed toward responsible action in the great community. Dewey’s mind was fertile when it came to discussing means, but vague and abstract when it came to talking about ends. The important thing was to direct the schools toward the moral needs of democracy; but here, the teacher’s own perceptions of those needs could hardly be discounted. Dewey himself advocated for a ripped-from-the-headlines approach to education that would lead to “the sober treatment of mundane problems.” (He favorably quoted Hegel’s line that “Reading the morning newspaper is the realist’s morning prayer.”)

The pragmatic impulse in Dewey relates to William James’ claim that the truthfulness of an idea lies in its “cash value,” meaning its ease of exchange as well as its ability to purchase results—in other words, its usefulness. For that reason, Dewey believed that education mainly involved “problem solving.” Teachers had to help students identify the problems, but again with reference to the interests of the child. From there, Dewey believed, children should devise their own experiments, build their own equipment, cooperate in designing their own results, and to be accountable to authority for the results. This destruction of the curriculum, whose sole purpose, Dewey thought, was to be a carrier of tradition, does have a point to it.

The traditional schools that Dewey was such a critic of typically lived up to his dismissive prejudices. Rote memorization, lesson plans, passive instruction, and spending a day sitting still and listening is unlikely to stir the hearts and minds of many children, especially boys. That one-sized-fits-all approach to educating has, I think, been definitively rejected, at least in theory. But Dewey substitutes for it another “one-sized fits all” approach, one where the student is directed by utility and interest alone. This is because Dewey’s theory largely reverses the traditional model: instead of taking its cues from the interests of the leisured classes, it takes them from the working classes. Dewey thus shifts the default of the classroom so that the bright child and not the dull one becomes the problem. The irony is obvious: our brightest children are poorly served by our schools unless their parents have the means to put them in private schools, thus perpetuating the very class system that Dewey worked so hard to dismantle. In the 100 years since his reforms became the standard for education, our schools have become less egalitarian, not more so.

Giving The Devil His Due

Nonetheless, Dewey’s emphasis on hands-on and practical learning ought not to be lightly dismissed. Matthew B. Crawford, author of Shop Class as Soulcraft, has written intelligently about the atrophying of the mind that takes place when we think of ourselves as pure mind. He insisted on the wholistic “satisfactions of manifesting oneself concretely in the world through manual competence,” which make “a man quiet and easy,” for this competence seems

to relieve him of the felt need to offer chattering interpretations of himself to vindicate his worth. He can simply point: the building stands, the car now runs, the lights are on. Boasting is what a boy does, who has no real effect in the world. But craftsmanship must reckon with the infallible judgment of reality, where one’s failures or shortcomings cannot be interpreted away.

I, for one, am convinced that all the mental health problems epidemic among our young people would largely disappear if we got them more actively engaged in the physical world. And I think Dewey knew that, too.

He also correctly cast suspicion on our tendencies to quantify learning, especially through the grading system. The push for “high marks” would introduce competition into the educational enterprise, contrary to the communal spirit of education. Dewey insisted that the schools were microcosms of the larger community and should reflect the values thereof, and since community was a cooperative and not a competitive enterprise, the schools should eliminate traces of competition. Students were not learning for the purpose of development and growth but to satisfy artificial criteria created by adults, and this, too, was a perversion of the educational enterprise.

Dewey worried that his prescriptions would be turned into rigid dogma, and by the 1930s he expressed concern with the implemented reforms that reflected his own ideas and experiments. He did not openly recant of his errors, and one suspects this is mainly because he didn’t think he had made any. Rather, the problem was one of either misinterpretation or misapplication. One can hardly be blamed for the former, given how turgid and often contradictory is Dewey’s prose. As to the latter: what he would regard as an abuse of his thinking strikes the observer as simply a logical outworking of it. The rejection of external authority, the assumptions about the purity of the interests of the child, the declaration of parents and churches as agents of division, the notion that the efficacy of education can be determined only by its practical application, the belief that the fundamental purpose of education was to solve social problems, and the egalitarian leveling of the enterprise could only produce some deleterious results, no matter how noble the aspirations. It’s not that Dewey was simply wrong about everything, but where he was wrong he was spectacularly so, and where he was right the insights were often compromised by their one-sidedness.

But we largely live in his world now, where students know very little of their own history; where teachers know very little about what it is they are supposed to teach, and also burn out quickly because the demands of controlling the environment are so burdensome; where, because Deweyan schools are so expensive, the taxpayer pays a lot of money for poor results; where the space has been opened to the worst kinds of ideological machinations and indoctrinations because the purveyors believe they are solving social problems and creating the great community; and where schools and parents and churches are in perpetual antagonism with each other because parents will no sooner give up their children than churches will their beliefs. In that sense, “A Nation at Risk” might well have simply repeated what Flannery O’Connor once observed: whatever John Dewey said do, don’t do.