This summer marks the 10th anniversary of the death of Michael Brown. It is a decade marked far more by heat than light. One could even say that, as time has passed, events have confirmed the worst suspicions each side held for its opponent.

We know what we want freedom from. But do we have a vision of what freedom is for? Perhaps it’s time to look at the hope and goodwill our first president held out to fledgling Jewish communities, and to the promise of a thriving particularity.

Michael Brown, a Ferguson, Missouri, 18-year-old, died after being shot multiple times in an altercation with a white police officer named Darren Wilson. Early reports indicated that Brown was shot while holding his hands up or while fleeing Officer Wilson. But the facts complicated this narrative. On the one hand, multiple investigations exonerated Wilson, corroborating his claims that Brown charged him and engaged him in a physical altercation. On the other hand, there was abundant evidence to suggest that the Ferguson Police Department had a serious problem with racial bias. And so, while Wilson himself was innocent of any crime in the incident, it took place within an ecosystem in which injustice and bias was the norm.

These facts turned Brown’s death into a kind of Rorschach test, allowing anyone to see what they wanted to see. Those inclined to think of America in terms of systemic injustice can see Brown as one more young black man unjustly killed by the police; those who tend to think in terms of individual responsibility can see only that Officer Wilson was guilty of no crime.

The result was a firestorm of protests that reignited and reshaped debates over race in America. Ferguson solidified the Black Lives Matter movement as a powerful influence in politics and media, and gave rise to a new generation of civil rights leaders as well as new language and a new issue set.

The impact is easy to trace. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) departments were opened in academic, corporate, and government institutions. The New York Times published the 1619 Project, a Pulitzer Prize–winning work of revisionist history that reframes America’s founding myth around the institution of chattel slavery and not the personalities and ideas of the founding. A new race consciousness permeated Hollywood, reshaping unwritten criteria for casting and awards.

The Black Lives Matter organization, however, has not been without controversy. Along with accusations of grift and corruption, it was roundly criticized for making the nuclear family a target for deconstruction, and it stirred new ire in the fall of 2023 when chapters around the country joined the Democratic Socialists of America in celebrating the Hamas massacre of Israelis on October 7.

Meanwhile, the American right, which largely objected to narratives of systemic racism, embraced Donald Trump in 2015 and remade their party in his image. Trump’s entry into politics actually came several years earlier, as one of the most vocal and prominent purveyors of the “birther” conspiracy theory accusing Barack Obama of not being a natural-born citizen. During his campaign and in the years since, Trump has trafficked in racist and xenophobic rhetoric about Muslims, immigrants, and refugees, and he helped mainstream alt-right figures like Steve Bannon, militant white nationalists like the Proud Boys, and white supremacists like Nick Fuentes.

These two currents in American culture were a sort of Hegelian nightmare, each one reaching further into radicalism to match the rhetoric and ambitions of the other. By May of 2020, the country was ready to explode. An incident in Minneapolis lit the fuse.

While arresting a black man named George Floyd for a petty crime, a white Minneapolis police officer named Derek Chauvin kneeled on his neck. Floyd’s injuries were catastrophic, and he died shortly thereafter. Video of the arrest, shot by a bystander, went viral online, and the outrage erupted in violent street protests from New York to Portland.

Anti-Semitism’s reemergence serves as final, damning proof of the corruption of the political ideologies that dominate our culture.

This case ended very differently from Wilson’s. Here, a jury of Chauvin’s peers found him guilty of 2nd-degree unintentional murder, 3rd-degree unintentional murder, and 2nd-degree manslaughter. It marks the first conviction of a white police officer in the death of a black man in Minnesota history.

Somehow, both ends of the ideological spectrum still saw the event as evidence of injustice. On the left, Floyd’s death proved (again) that police have a license to brutalize black men, and Chauvin only faced consequences because he was caught on video. On the right, Floyd was framed as a petty criminal and drug user who resisted arrest and suffered the consequences, and Chauvin was seen as the subject of a witch hunt.

Radical Binaries

That summer was one of the most polarizing of my lifetime. It marked a new era of tolerance for protests and street violence. Police were ambivalent about escalating their efforts at restraint, given the nature of the protest, and the progressive leadership of the local governments were sympathetic to the protestors’ cause.

Much of the mainstream media shared these sympathies, which led to now-infamous moments, as when CNN used a chyron reading “Fiery but mostly peaceful protests after police shooting” while airing footage of burning buildings in Kenosha, Wisconsin, or when NPR ran an interview in defense of looting.

In June, New York Times Opinion editor Bari Weiss published an op-ed from Tom Cotton, a sitting U.S. senator, suggesting the deployment of the military to squelch the riots. Younger and more progressive staffers were outraged. The internal dissent and lack of support from the executive leadership of the paper led to Weiss’ resignation, as well as that of James Bennet, the Opinion Page editor. Their exit was seen by many as a sign that a generation of young, progressive activists were willing to weaponize HR departments, social media, and other means of protest to reshape institutions like the Times in their image.

In August, Kyle Rittenhouse, a 17-year-old who shot three protesters, killing two, became the embodiment of white privilege for the left and a folk hero for the right. In September, Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg died. Ginsberg was an icon for progressives, and her replacement, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, was in many ways her ideological opposite. The swap secured a conservative supermajority on the Court just as Donald Trump’s presidency was ending, and ramped up a sense of loss and despair among progressive activists.

These are just a handful of the polarizing events of that summer, and of course I’ve made no mention of the COVID pandemic and shutdowns—events that colored all the above and became racially charged in their own strange ways. Likewise, I’ve made no mention of the presidential campaign that was taking place at the time, which would climax not in the American tradition of a peaceful transfer of power, but in a right-wing riot instigated by the Proud Boys and encouraged by Donald Trump on January 6, 2021.

It is a story without heroes. There are only constituencies gathered around oppositional ideologies whose radicalism and corruption continually prove their opponent’s worst accusations. It seemed like an unbridgeable divide, as though these two poles would repel one another further and further until they tore the nation’s social fabric. And then came October 7, 2023.

When 1,200 Israelis were slaughtered by Hamas on that black Saturday, the worst elements of left and right found a common cause: anti-Semitism. For the left, it was the ideological anti-Semitism of identity politics and anti-colonialism. For the right, it was historic anti-Semitism in the form of conspiracy theories, social Darwinism, and religious contempt. The result was a bizarre unity of opinion from the likes of the Squad, Candace Owens of the Daily Wire, Ivy League political science departments, and Tucker Carlson.

One can hardly imagine the anti-Semitism of Ilhan Omar or the terrorist apologia of Rashida Tlaib being tolerated in the party of Daniel Patrick Moynihan. It’s equally hard to imagine the party of Reagan embracing Vivek Ramaswamy, Steve Bannon, or Matt Gaetz. And yet here we are. For a decade now, political parties have allowed their constituencies to expand in ways that would have been unimaginable in previous generations. Parties no longer practice the kind of institutional hygiene that keeps the most radical elements out.

Jonah Goldberg has often lamented that this is a reflection of the political party’s inherent weakness—which I think is true. It’s a reflection of the coalition’s fragility that it won’t practice any sensible discipline against its most radical members.

But it also reflects a lack of vision. The left and right share a reactive and nihilistic spirit. For the progressive left, it’s focused on the deconstruction of social institutions and centers of cultural power. For the right, that spirit is focused on undoing the agenda of progressives, which is summed up perfectly in the slogan “Make America Great Again.” In spite of the positive tenor of the phrase, the agenda it represents is almost entirely reactionary, from building the wall to tearing down portions of the administrative state. Even the more mainstream elements of our political parties are defined negatively. Most “old school liberals” among Democrats will argue that the coalition needs to stick together in spite of the more fringe elements because Donald Trump is a unique threat to the republic. Most “old school conservatives” among Republicans will argue that whatever Trump’s faults may be, the left is a greater threat.

Americans who are less ideologically motivated, whose lives are not fueled by politics, arrive at the polls with nothing greater to ask themselves than “Whom do I dislike more?”

The Canaries in the Coal Mine

Many have pointed out that this eruption of anti-Semitism is final proof of the “horseshoe theory” of political polarization, which posits that as ideology polarizes into opposing political factions, the most extreme elements of either will bend toward each other and converge around common, radical ends. That anti-Semitism is what has fused this coalition evokes another political theory—that Jews are the canaries in the coal mine of culture.

Historically speaking, the emergence of anti-Semitism is always a sign of something poisonous taking root in a society. It doesn’t just spell danger for Jews; it spells danger for everyone. As Bari Weiss has put it, “What starts with the Jews never ends with the Jews.” The rise of anti-Semitism in Nazi Germany, Soviet Russia, and half a dozen Middle Eastern states was quickly followed by other forms of violence, tyranny, and authoritarianism.

As a Christian, I recognize something spiritually dangerous at the root of anti-Semitism. As Robert Nicholson, president of the Philos Project, has put it, anti-Semitism isn’t simply ethnic hate, though it certainly isn’t less than that. It is a hatred of the God who revealed himself to the world through the Jewish people, whose revelation declared the value of human life and human dignity, values that are the basis of Western civilization.

Christians of different traditions hold conflicting views on the Jewish people in the present age, and the age to come. While I’m not particularly compelled by any particular theory of the end of days (I’ve long said I’m an adherent of “meh”schatology, since no single theory strikes me as particularly convincing), I am thoroughly convinced that God is not done with his covenantal promises to them. History itself seems to testify to this. The Nazi regime is gone. So is the Soviet Union. So is pretty much every tribe and nation that set as a goal the destruction of the Jewish people. As Walker Percy noted, you’ll be hard pressed to meet a Hittite or an Assyrian walking the streets of New York or London. And yet, here are the Jews, in almost every city and nation, bearing witness to God’s covenant with Abraham by the mere fact of their existence.

That remarkable fact ought to serve as another kind of warning. Rejecting anti-Semitism isn’t just good manners or principled pluralism; cultures that pursue the persecution or eradication of the Jewish people tend to vanish. If nothing else, resisting anti-Semitism is an act of cultural self-preservation. Theologize it or don’t; the historical record speaks for itself.

The success of the principles of liberty would be measured by the flourishing of its marginal communities.

Anti-Semitism’s reemergence here and now ought to serve as final, damning proof of the corruption of the political ideologies that have come to dominate our culture. It reveals a nihilistic, even suicidal impulse at the heart of our politics and ought to invite sober reevaluation of what drives it.

A Spirit of Liberality and Philanthropy

If Jews are the canary in the coal mine of culture, and a threat to them signals a threat to all, is the opposite true? Is it a sign of civic and social health when Jews are treated with dignity and equal rights? I think so, and one need look no further than the American founding to understand why.

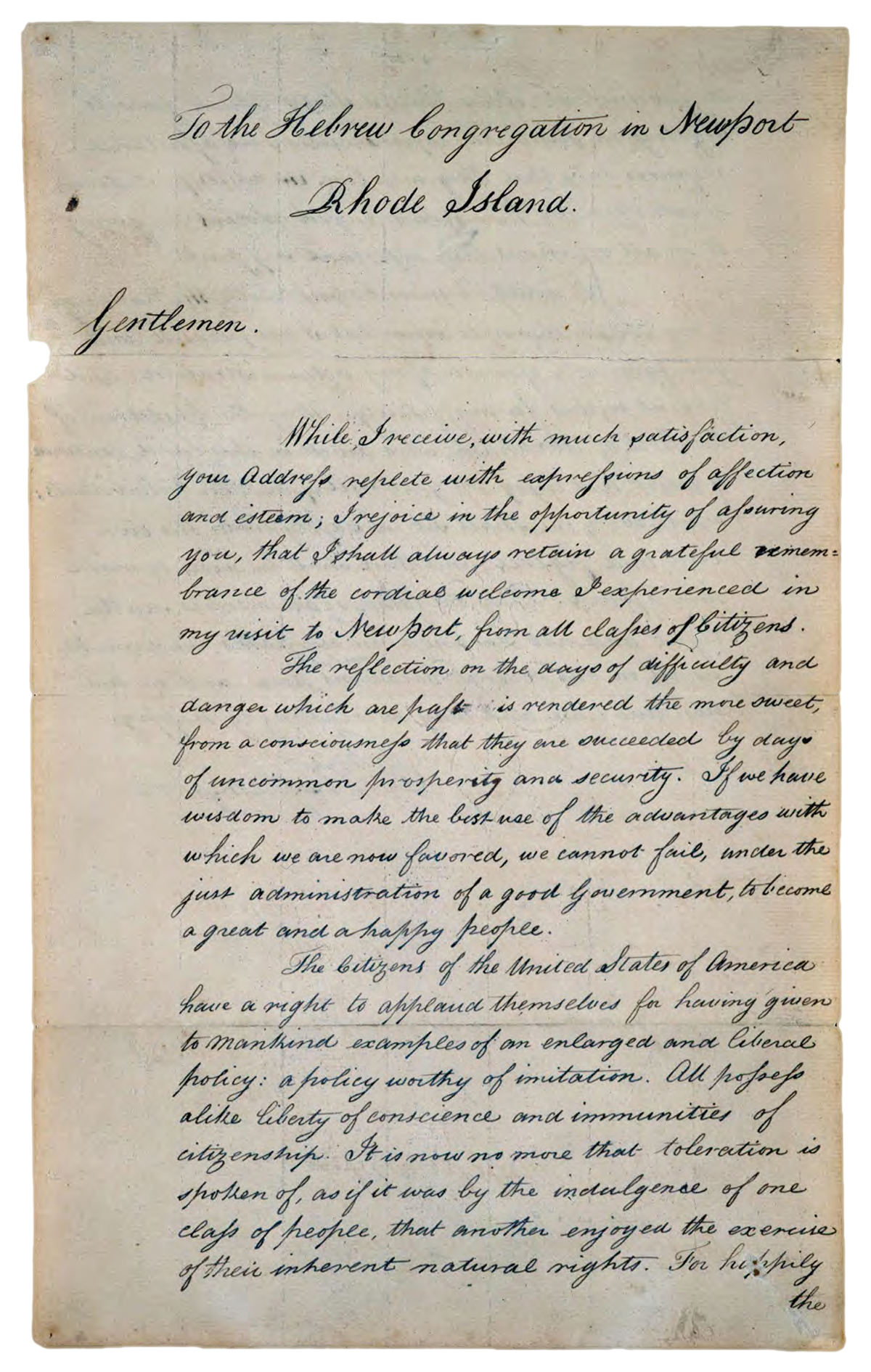

In 1790, a year after George Washington was sworn into office, he received three letters of congratulation from Jewish congregations around the new nation. Washington replied to each one, expressing his gratitude not only for their words but also for the safe harbor they’d found in the new nation. His hope was that, in this way, America would be a model to the nations of healthy liberalism. To the Hebrew Congregation in Savannah, Georgia, he wrote:

I rejoice that a spirit of liberality and philanthropy is much more prevalent than it formerly was among the enlightened nations of the earth; and that your brethren will benefit thereby in proportion as it shall become still more extensive. Happily the people of the United States of America have, in many instances, exhibited examples worthy of imitation.

He ends the letter with a remarkable benediction:

May the same wonder-working Deity, who long since delivering the Hebrews from their Egyptian Oppressors planted them in the promised land—whose providential agency has lately been conspicuous in establishing these United States as an independent nation—still continue to water them with the dews of Heaven and to make the inhabitants of every denomination participate in the temporal and spiritual blessings of that people whose God is Jehovah.

As Rabbi Meir Y. Soloveichik, in a recent Commentary magazine essay, describes it, Washington “was making American Jews feel as if they truly belonged. … The God Who performed miracles for Jews in the past is the same Deity Who performed miracles for America in the present. The God Who saved Israel from tyranny saved America from tyranny as well. The Jews were to be welcomed in America not only because of the ideals of equality, but also because of the way in which the Jewish story inspired America itself.”

Washington wasn’t saying these things in an effort to secure Jews to his coalition; at the time, there may have been a total of 1,000 Jews in the entire fledgling nation. Rather, he recognized that the success of the principles of liberty by which the new nation was founded would be measured by the flourishing of its marginal communities. For Jews, liberty wasn’t an abstraction. Their ability to maintain their communal identity depended on their ability to thrive as outliers, to be as insular as they required, and to enjoy the rights and protections of citizenship when needed.

Washington expressed that understanding beautifully in the letter he wrote to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport, Rhode Island:

May the Children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.

Here, he references Micah 4:4, a passage that would appear more than 50 times in his speeches and correspondence, including his Farewell Address. “But they shall sit every man under his vine and under his fig tree, and none shall make them afraid.” Micah the prophet writes these words to Jewish exiles, promising them a future restoration of their nation in which they will no longer live under the thumb of Babylonian oppression. Washington saw a similar liberation in the American story and hoped for the nation to be an example to the world of the kind of prosperity and moral beauty that could emerge from pluralism and liberty.

As he saw it, a healthy nation would give birth first not to national unity but to thriving particularity. The litmus test for liberty was whether or not Jews, a marginal community in the new nation at best, could thrive and flourish as Jews firstand as citizens second.

Living Up to Founding Creeds

While Washington’s letters to these Hebrew congregations are a remarkable testament to his vision of liberty, praise here deserves an asterisk. Because of course, not everyone was invited to sit under their own vine and fig tree in the new nation. According to the 1790 census, there were almost 30,000 slaves in Georgia and 1,000 in Rhode Island when these letters were exchanged, which was just a fraction of the nearly 700,000 slaves in America at that time. There is something right about calling slavery the nation’s “original sin,” as it stains the legacy of our founding.

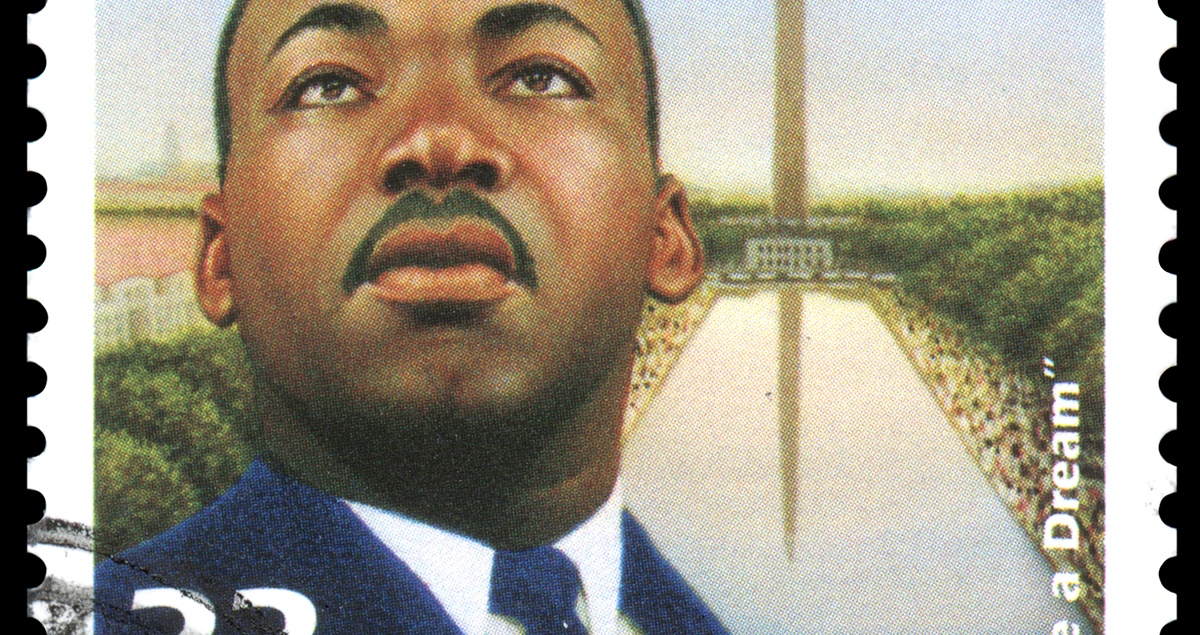

But our nation’s better angels emerged when its leaders called us to fidelity to its first principles, not when they rejected them. This was the message of Fredrick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, and it was the message of Martin Luther King Jr.

In a 1967 speech to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, King lamented a nation that had “a high blood pressure of creeds and an anemia of deeds.” Our problem was not a failure of moral imagination or vision, but of action; we weren’t living up to the promise of our founding creeds. “Let us be dissatisfied,” he continued, “until that day when the lion and the lamb shall lie down together, and every man will sit under his own vine and fig tree, and none shall be afraid.”

The civil rights movement King led was birthed from America’s Black churches. His demand for a better, more just world was inextricably linked to that spiritual community, both in how it formed him as a person and how it informed his vision of that more just world. In this we find a link between his vine and fig tree to that of America’s earliest Jewish citizens and to Washington: a purpose beyond politics and the freedom to pursue it without fear.

A healthy nation would give birth first not to national unity but to thriving particularity.

This strikes me as the missing element in our contemporary conversations about race and justice in America: a vision of liberty. Because the orientation of our parties and their accompanying ideological movements is negative and destructive, it is easy to find an articulation of what people want freedom from: theocracy, woke ideology, white supremacy, drag queens, or religious zealots.

What is missing is a vision of what that freedom is for. The Israelites were freed from bondage in Egypt so they might worship their God. The exiles longed to flee Babylon so they might live under their vine and fig tree unafraid. Jews in the newborn United States wanted freedom to embody their faith without fear. Black leaders of the civil rights movement wanted access to the promises of the founding.

Those who are animated by the scandals du jour of contemporary politics need to be asked about their own vine and fig tree. What do they hope to go home to after they’ve achieved victory in their culture war? What will give them meaning when the battle is over? What stops them from pursuing that meaning now?

For 20 years, American intellectuals have lamented the erosion of our social infrastructure and the collapse of our institutions. The world is increasingly a hard place in which to find friends or purpose, and lonely people are turning to politics as one of the few energetic spaces in American life that purports to offer meaning. But contemporary politics, so driven by grievance and nihilistic in spirit, can only animate them to become more polarized and more destructive.

The decade since Ferguson has proved that again and again. At every turn, whether confronted by questions about race, the rise of extremism, political violence, the COVID pandemic, or global conflicts in Ukraine and Israel, the impulse of our culture is to react in ways that leave us more polarized and less united than before.

It may simply be that the problems of our politics will not be solved in the realm of politics. Instead, those who wish to interrupt the suicidal momentum of our culture need to find other spaces in which to invite people into a sense of meaning, purpose, and belonging.

My hope is that American Jewry can provide a vision for that as a community with a sense of identity and a telos that transcends politics. Failing to find that, I fear that they’ll provide a more terrible example—as canaries in the coal mine, foreshadowing the collapse of our experiment with liberty.