Historians studying immigrant religion in America don’t generally spend a lot of time on Norwegian Lutherans. We’re a fairly small group, after all. But if you’re rash enough to “drill down,” as they say, you’ll encounter a welter and confusion of tiny Lutheran church bodies that split off and recombine like some protean monster out of a Lovecraft story. A book on Norwegian Lutheranism in America will generally contain a chart resembling some OCD attempt to organize a can of worms. (Don’t worry, I won’t include one here. I’m concentrating on one church body—the Lutheran Free Church (LFC)—and the broad brush is my tool of choice.)

The name Georg Sverdrup may not be familiar, but he was key to forming something new in the history of Lutheranism—a free congregational church in which laypeople were empowered and the spirit was unhampered. But freeing the Gospel from dead traditions can result in a legal mess.

The root cause of this sectarianism may have been the considerable success enjoyed by the Danish kings (who ruled Norway from the 14th to the 19th centuries) in educating their people. They decreed that each of their subjects should get enough schooling to read the Bible and, after the Reformation, to be familiar with the teachings of Luther’s Small Catechism. The catechism was supplemented by a rather larger book, an explanation written in 1737 by Bishop Erik Pontoppidan. That explanation was subsequently revised more than once, notably by Pastor Harald Ulrik Sverdrup (pronounced SVAIRD-roop; 1813–1891), a prominent Norwegian churchman and politician.

The name Sverdrup gave off a nice ring when you dropped it in those days. Harald’s uncle Georg was among the presidents of the assembly that drafted Norway’s constitution in 1814. Harald’s brother Johan was the country’s first parliamentarian prime minister. Their cousin Otto Sverdrup, an arctic explorer, shared command with Fridtjof Nansen on two voyages. Another, younger relation would give his name to a standard unit for measuring seawater flow.

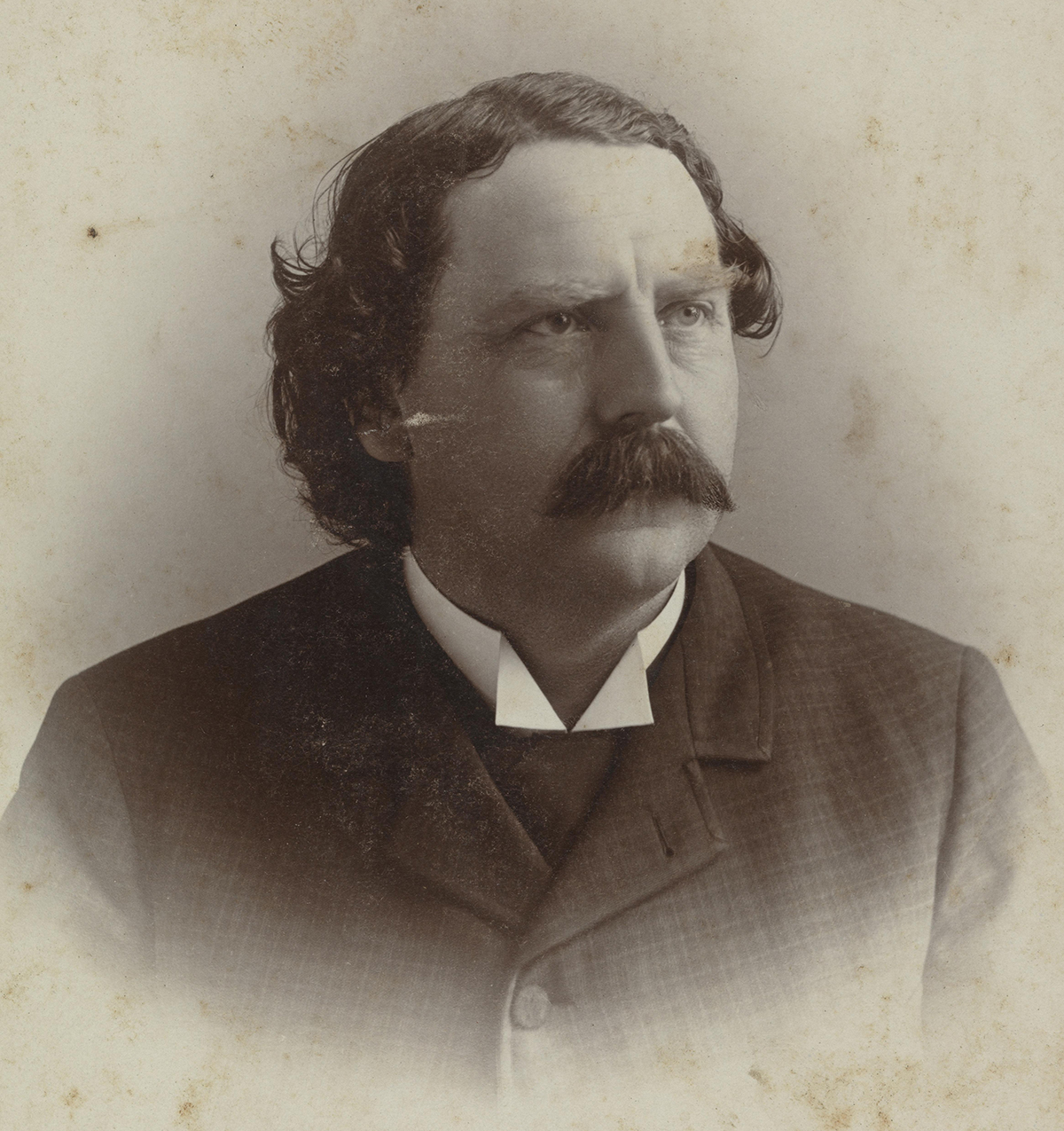

Harald’s son Georg (pronounced GAY-org; 1848–1907), the subject of this article, could be expected to lay his own set of laurels on the family altar. Born in Balestrand, where his father was pastor, he proved a gifted scholar from an early age. He took his degree in theology from the University of Christiania (now Oslo) in 1871, going on to study Semitic languages at the University of Paris and various schools in Germany.

But a friendship altered the course of his life. Sven Oftedal (1844–1911) from Stavanger, whom Sverdrup first met at the university, was a member of another prominent Norwegian family, one that produced politicians, religious leaders, scholars, and publishers. The two young men renewed their acquaintance in Paris, forming a symbiotic partnership—Sverdrup quiet and reserved, Oftedal voluble and gregarious. Sverdrup was the Hebrew-language man, Oftedal the Greek maven. For the rest of their lives, they would complement and support each other as colleagues and allies. Both were intelligent young Christians, peculiar products of Haugeanism, a social and religious movement not generally noted for its intellectual vigor. Nevertheless, the world, they understood, was changing all around them. Sverdrup and Oftedal believed they’d figured out a way to shape that change.

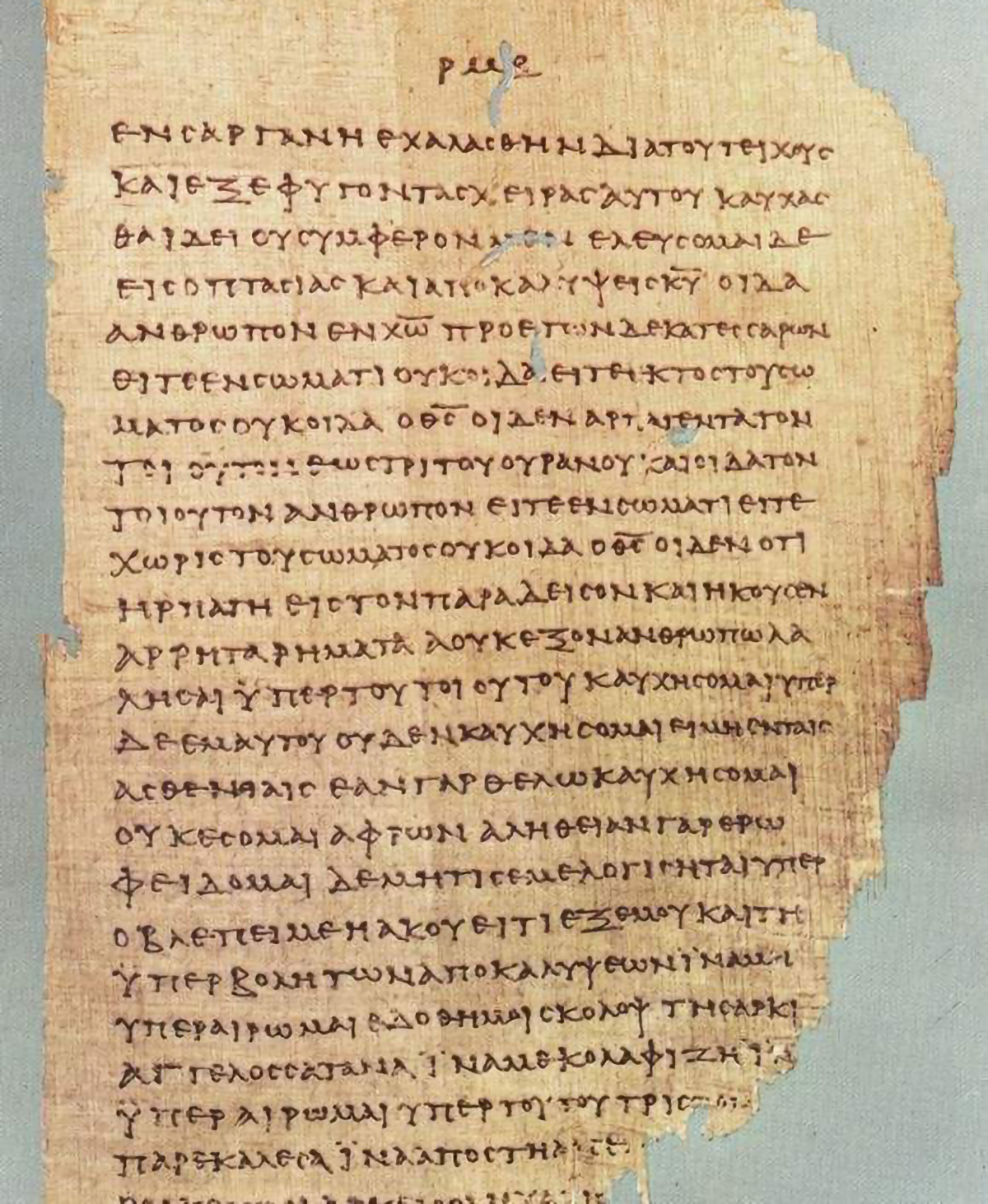

Between them, they were hammering out a new idea—for Lutherans, a radical one. The Christian church, they decided, had gone wrong at a very early stage, when Rome began dominating the other local churches. Based on their reading of the New Testament (in the original Greek, of course), they concluded that the early church was organized around the local congregation. Each congregation was free and equal. No central authority except the Holy Spirit dictated to it. It was then, they believed, that the church had spiritual power. This model must be reclaimed. Lutheranism didn’t require any particular form of church government. Luther himself had little to say on the subject. Why not try Lutheran congregationalism—that is to say, a Lutheran free church?

At this point I need to explain a little about the remarkable social and religious movement, Haugeanism, from which these two young men sprang.

Pietism and a Reborn Church

The Pietist impulse rose side by side with Romanticism, growing from much the same intellectual (sometimes anti-intellectual) soil. The people at large were sick of being ruled by men of the Enlightenment. Newton had, through no fault of his own, become the effective god of the age. The universe, it was claimed, was a closed system. All important questions had been answered, or soon would be. Christianity, so far as it survived in this environment, was reduced to moralism, stripped of the miraculous and the passionate.

Man, however, cannot live by bread alone. The human heart remained what it had always been (and still is—let the reader understand), for good and for evil. Beneath the surface, the Western world was pulsing with a repressed, half-conscious thirst for wonder, for the transcendent. Pietism, born among German Lutherans, offered a cup of cold water to souls parched by Rationalism. Like the Romantics, the Pietists aspired, looked for hope beyond the horizon. Unlike the Romantics, they moored their teachings to solid, traditional morality and doctrine.

Each congregation was free and equal. No central authority except the Holy Spirit dictated to it.

In Norway, there was a farmer’s son named Hans Nielsen Hauge (pronounced HOW-geh; 1771–1824). He had the minimal education common to his class but was unusually bookish and scrupulous. In April of 1796, while plowing his father’s field, he experienced what he called his “spiritual baptism,” an ecstatic conversion experience that filled him, he recalled, with love for God and neighbor. He took it for granted that he must now help other people to have the same experience. So he began traveling (mostly by foot) from place to place in that mountainous country, leading small meetings in homes. He wrote several books, which he packed on his back and distributed. (Hauge was no systematic thinker; he simply poured his heart out onto the paper. Sometimes he goes on for pages without a period or a paragraph break.) He also had a practical side, spreading modern agricultural technology among the farmers and assisting in the establishment of startup businesses. He himself became a prosperous entrepreneur in Bergen (he plowed the profits back into his ministry).

The difficulty was that he was breaking the law. The Danish-Norwegian Conventicle Act of 1741 made it illegal for any layman to lead a religious meeting without a clergyman present. Surprisingly innocent in some ways, Hauge simply assumed that, since God had called him, he couldn’t possibly be violating any lawful ordinance. Even if magistrates disagreed, surely the king would understand. After repeated brief arrests, Hauge was imprisoned in 1804, charged with various crimes. He remained mostly in confinement until 1814. By then, enforced idleness had broken his robust health. But in his later years, even churchmen and government officials would come to pay him their respects on the farm his friends had bought him. His movement was no cult of personality; others took up the work and carried it on with great success in both Norway and America.

Starting from Scratch

When I do lectures on Lutheran Free Church history, I have to break one important fact gently—Hauge and his followers were liberals in their time. The political party most of the Haugeans joined was the “Venstre” (Left) or “Liberal” Party. It was this party that Georg Sverdrup’s uncle Johan represented. Thus, we need to keep in mind as we study Georg Sverdrup’s story that he was a liberal—in some ways even a radical—in his day. Of course, at the time, liberalism essentially meant the view that the lower classes deserved economic opportunity and a larger role in running the world. That’s what Johan Sverdrup’s Venstre Party was all about.

The Pietist impulse rose side by side with Romanticism, growing from much the same intellectual soil.

This division between liberal and conservative followed the Norwegian immigrants to America. (Indeed, organized immigration from Norway first began with a sloop-load of Quakers and Haugeans who embarked from Stavanger in 1825.) The Norwegian government and the state church both adamantly opposed this exodus. The only possible reason anyone would want to go to America, they reasoned, was either to get rich (which was covetousness when the poor did it) or to rebel against God’s constituted authorities. For that reason, they refused for decades to send any Norwegian pastors to minister to the emigrants. When the first pastor finally did show up, he was a Haugean who got himself ordained in Chicago.

Thus, the initial state of Norwegian Lutheranism in America was anarchic, a flock without shepherds. Gradually, however, the sheep began organizing. But the Norwegians were (as they remain) quietly contentious.

When Norwegian state-church pastors finally did arrive, they attracted those settlers who were comfortable with the old state-church model. This group formed the Synod of the Norwegian Evangelical Church in America (generally known as the Norwegian Synod), which had no seminary of its own. To educate their pastors, they sent them to the Germans at the Missouri Synod seminary in St. Louis. The Norwegian Synod was the largest Norwegian American Lutheran church body.

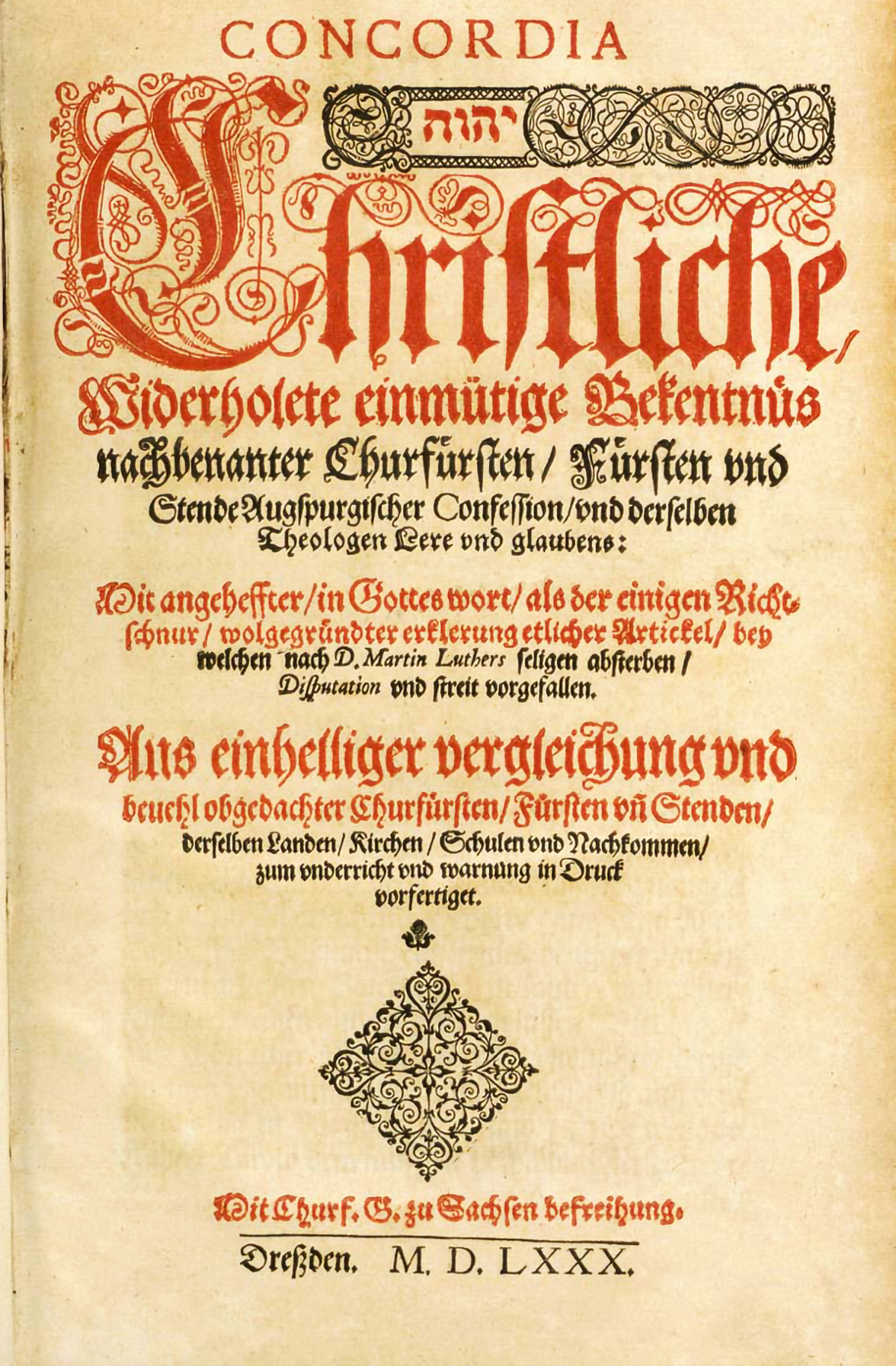

The Haugeans, a large minority of the new immigrants, were for their own part giddy with religious liberty and disdainful of the Synod, which they considered formalistic and lukewarm. They hadn’t forgotten the state church’s persecution of Hauge. To them, the Synod was “high church,” “confessional” (referring to the Lutheran Augsburg Confession and Book of Concord), cold, desiccated, and dead. In the spirit of Hauge, they wanted “living” Christianity—fiery, committed, revivalist. They organized their own church bodies … several of them. For some time, the original Haugean group, commonly known as the Hauge Synod, couldn’t make up its mind whether to build a seminary. Some of them weren’t convinced an ordained clergy was even necessary. A more moderate faction joined with a group of Danes to form the “Conference of the Norwegian-Danish Evangelical Lutheran Church in America,” generally known as the Conference. They established a small seminary that they called Augsburg Seminarium in Marshall, Wisconsin, in 1869, the first Norwegian American Lutheran seminary. A pastor from Norway named August Weenaas (VAY-noace) was its first president and almost its entire faculty.

In 1873, the Conference moved the seminary to Minneapolis. That same year, Weenaas persuaded young Sven Oftedal to come over and become professor of the New Testament. The following year, Georg Sverdrup followed, with his wife, to be the Old Testament man.

It hadn’t been an easy decision for Georg. Most Norwegian immigrants were poor folk who didn’t really wish to leave their families and the beautiful (if economically marginal) land of their birth. They emigrated out of desperate hope for a better life. Georg, on the other hand, could expect only privilege and advancement if he stayed in Norway. His educational attainments and family connections would have opened every door. No office in the country, beneath that of king, would in theory be barred to him.

But he was now convinced there was no way to achieve his free-church dream in Norway. The state church was too conservative, too entrenched and hidebound. When he tried to raise enthusiasm for reforming it on congregational lines, he was laughed at. He could have his career, it seemed, but only at the cost of his dream.

“I have offered up my Isaac,” he wrote to Oftedal. “I will come.” This is the challenge and conundrum of liberty in every place and time—the gamble, the bet that makes or breaks you. In America, there was no state church. Never before in history had there been an opportunity to build a Lutheran church body from scratch, on new-dug foundations with no underlying stratum of an older church structure. (Even the Missouri Synod Lutherans had started out with a bishop from the old church.) If the free Lutheran church was ever to be built, the United States was where it could be done. Then the world would see.

Now all they had to do was convince the Norwegian Americans.

Empowering the Laity

In 1874, before Sverdrup arrived, an article signed by Sven Oftedal and Professor Weenaas appeared in a Norwegian-language paper. It was called “The Open Declaration.” It attacked the Norwegian Synod, calling it “rationalistic” and accusing it of “Catholicism.” It charged the Synod with promoting spiritual indifference, with being controlling and contemptuous of revival and spiritual life.

The Declaration’s intent was to unite the Haugean elements of the Norwegian American community behind Augsburg Seminary and the free-church vision. The result was quite different. Condemnations came from as far away as Norway, and even members of the Conference criticized it. Permanent enmities were conceived in its aftermath. Two years later, Weenaas himself renounced the Open Declaration and returned to Norway. This left Augsburg College and Seminary in the young, radical hands of Sverdrup and Oftedal.

The pair conceived a plan to shape Augsburg into a facility for instructing pastors in Lutheran free-church principles. A college department had been added in 1874, but Sverdrup and Oftedal reconfigured it into a pre-seminary program. “The servant pastor” was a theme to which they would return for the rest of their lives. No longer would the pastor be an aristocrat in his community, as he had been in Norway. The free-church pastor would be a Christian among Christians, not dictating but leading and coordinating lay activities as a conductor leads a choir.

Sverdrup declared Augsburg a “Greek School,” as opposed to traditional universities and seminaries, which he called “Latin Schools.” The idea was that Greek—the language of the New Testament—prepared pastors for practical work in the congregation. Latin, on the other hand, was a nonbiblical language, the language of the classics, of elite studies that generated scholarly arrogance. The goal of Augsburg, he wrote, was “menighedsmessig presteuddanelse,” pastoral education oriented to the congregation.

Another favorite term was barnelærdom, a Norwegian word with no English equivalent. Literally it means “children’s education.” To Norwegians, it signified the Lutheran instruction they’d received in confirmation class, the material contained in the Small Catechism and H.U. Sverdrup’s revision of Pontoppidan. Master this material, Sverdrup argued, and you have all the theology you really need. Studying the minutiae of Lutheran doctrine, particularly the massive Book of Concord, though not a bad thing in itself, added little of practical use and tended to puff pastors up.

Another purpose of this emphasis on barnelærdom was to raise the status of the layman. If advanced scholarship was required to do the work of the church, then only pastors were qualified to do most anything. Such a division horrified Sverdrup. The free church must be the body of Christ described in 1 Corinthians 12. Everyone must exercise their gifts as God had equipped them.

The free-church pastor would be a Christian among Christians, not dictating but leading and coordinating lay activities as a conductor leads a choir.

Lay activity was in fact a central issue in all Sverdrup’s controversies. This tension over lay activity went back to Hauge himself. The Fourteenth Article of the Augsburg Confession was often interpreted to forbid anyone but an ordained minister from leading any religious gathering. But informal “edification meetings,” led by laymen, were central to Haugeanism and strongly encouraged by the Haugean pastors.

A Church Divided

Sverdrup’s and Oftedal’s emphasis came to be known as “the New Direction,” and it provoked sharp division in the Conference. As the two professors published editorials and debated fiercely, often in Folkebladet (The People’s Paper), the newspaper they established, opposition grew, inside and outside the Conference, and financial support and enrollment at Augsburg plummeted. Oftedal made a tour of friendly congregations in newer Norwegian settlements, chiefly in northwestern Minnesota and eastern North Dakota, succeeding in raising (during a time of recession and grasshopper plagues) an endowment of over $50,000. The school’s situation improved by stages until 1890.

By that time, there were plans for a merger of several Norwegian American church bodies, excluding the Norwegian Synod but including Augsburg’s Norwegian-Danish Conference. It was to be called the United Norwegian Lutheran Church of America. Initially, Sverdrup and Oftedal were enthusiastic promoters of this merger. They had received assurances that Augsburg would be the sole seminary of the new church body. It seemed to them their great dream was about to come to fruition. Most of the non-Synod Norwegian American pastors, from this point on, would be trained as Free Lutherans at Augsburg. Sverdrup assumed that Augsburg’s college division would be included in this arrangement, unifying United Church thinking behind his “Augsburg Plan.”

But another group within the merging bodies, “The Anti-Missourian Brotherhood,” had just established a college of its own, Saint Olaf, in Northfield, Minnesota. They proposed that Saint Olaf should be the official college of the United Church. Sverdrup viewed this as a breach of the previous understanding. His critics, however, were concerned, beyond theological and church governance considerations, with academic standards. There was a perception, as Carl H. Chrislock wrote in his history of Augsburg, From Fjord to Freeway, “that Augsburg tended to substitute piety for scholarship.” This was ironic considering Sverdrup’s impressive personal academic credentials, but it was also more than a little justified by his publicly stated positions.

Both sides dug in their heels. The new United Church demanded that Augsburg transfer all its property to it. Augsburg’s board of trustees refused, arguing that they had no legal authority to take such action, as the school belonged to the free congregations.

In 1893, a group of Augsburg supporters gathered at the United Church convention to form an association they called “The Friends of Augsburg.” That same year, other United Church members established a new, rival seminary elsewhere in Minneapolis. By this point, Augsburg’s membership in the United Church had been reduced to a technicality.

At the 1895 convention, Sverdrup and Oftedal were denied seats. The United Church then expelled 12 congregations for their support of Augsburg. About 100 more congregations followed them out voluntarily. This was the true beginning of the Lutheran Free Church.

In 1896, the United Church sued the Lutheran Free Church for ownership of Augsburg. A Hennepin County judge ruled in their favor, but the LFC appealed. In 1898, the Minnesota Supreme Court reversed the decision based on a legal technicality. By now both sides were ready to compromise. The LFC retained Augsburg College and Seminary in return for part of its library and the entire endowment fund Oftedal had labored so hard to raise.

Through the years that followed, the Lutheran Free Church remained one of the smaller American Lutheran church bodies. The wounds of the controversial years lingered, but Augsburg persisted, the center and heart of Free Lutheranism in America.

The Free Church Today

Georg Sverdrup served as president of Augsburg College and Seminary until his death in 1907, aged only 58. Many of his writings were collected posthumously in a six-volume set of Samlede Skrifter (Collected Works), edited by Andreas Helland.

And what of the Lutheran Free Church remains?

It was with the LFC as with so many idealistic schemes, religious and political. It did not long survive the passing of the visionary generation. The LFC continued as a church body for several decades, but its raison d’etre seemed more and more obscure. (It didn’t help that Sverdrup wrote only in Norwegian.)

In 1960, a group of Lutheran church bodies voted to merge into a new denomination called the American Lutheran Church (today part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America). The LFC, with its congregational polity, took a little longer making up its mind. Congregations and pastors still holding to Sverdrup’s principles mistrusted the new church body. It took three referendums before a majority of the congregations finally agreed, and they entered the merger in 1963. Augsburg Seminary was then folded into Luther Seminary in St. Paul, but Augsburg College continued as a four-year institution (which rejoices today in the name, Augsburg University).

A small group of recalcitrant congregations gathered in Thief River Falls, Minnesota, in 1962 to form a legacy body, which they wished to call “The Lutheran Free Church (Not Merged).” (Seriously.) They were sued by the new ALC, which, in the spirit of the dog in the manger, claimed sole right to the Lutheran Free Church name, and prevailed in court. The new group then took the name the Association of Free Lutheran Congregations (AFLC). I’m a member of that body and served as librarian for their Bible college and seminary in Plymouth, Minnesota, until my retirement. We follow the Lutheran Free Church tradition and, faithful to that tradition, we are small.

It’s hard to deny that, in some ways, history seems to have vindicated Sverdrup’s critics. The Norwegian Synod theologians, in line with Missouri Synod thinking, had warned that reliance on enthusiasm and subjective experience would inevitably end in a slide toward doctrinal subjectivism. Which is precisely what happened, whether inevitably or not. A friend who attended Augsburg in the 1970s, himself a theological liberal, once told me that the way Augsburg taught the Bible even then was “a crime. They aimed to demolish our faith.” Today, Augsburg has a Muslim chaplain on staff and holds Muslim Friday prayers in their chapel, where they also host same-sex weddings.

On the other hand, the Pietists won their share of arguments, too. I don’t think many Missouri Synod pastors today mind if a layman leads a Bible study. And doctrine-centered church bodies have also been known to slide into liberalism (the new liberalism, of course, not Sverdrup’s kind).

As political radicals believe in perpetual, self-renewing revolution, Sverdrup the Christian radical believed in perpetual revival. The church must not be defined by “dead” doctrine but through the dynamic witness of living congregations, constantly reenergized by infusions of the Holy Spirit. Which should not be taken to suggest that their worship style was in any way “charismatic.” The liturgy was low church, centered on Scripture reading, prayers, hymns, and the sermon. The preaching could get fiery, but Sverdrup explicitly rejected speaking in tongues. Altar calls, however, were always in order.

And the LFC’s annual conference was explicitly not empowered to be a governing institution—it had no executive authority over the congregations. Rather, it was to be a “spiritual dynamo” (Oftedal’s words), its momentum holding the congregations forever on one course. Sverdrup affirmed Lutheran doctrine entirely, but he believed that, without “spiritual life,” doctrine was a dead thing, incapable of empowering the work of Christ’s body in this world. And that idea has sent roots deep down into all American Lutheranism.

The Georg Sverdrup Society today is devoted to getting Sverdrup’s works translated, so that if we Free Lutherans forget the core principles of the Free Lutheran movement, there will be no excuses this time. And now and then, driving past Augsburg on Interstate 94, I say a prayer for the school. I ask the Lord to give it back to us. A quixotic prayer, I know, but truly in the Lutheran Free Church spirit.