What would the essayist Lionel Trilling make of today’s American conservative movement? While Trilling would certainly be critical of what he called “irritable mental gestures,” it would be hard to maintain that there are “no conservative ideas in circulation” or that liberalism is the “sole intellectual tradition” in America. He was wrong back then and even more so today. We are awash in debate about the meaning of conservatism, who is conservative, whether conservatism has a future, and Trilling may be surprised at the number of people who think liberalism itself is dead.

It’s obvious that conservatism has splintered into a variety of factions and that the old “fusionist” coalition is dead. But what killed it? And what would it take to resurrect it for the 21st century?

There is deep division not only among left and right and so-called liberals and conservatives. Many liberals are now progressive and reject liberal positions on religion and speech; mainline conservatives are now derided as liberals who are missing the signs of the times. Since the early 2000s and the breakdown of fusionism, the conservative project has been fragmenting into multiple camps. Today there are varieties of post-liberals, Catholic integralists, pro-Trumpers, anti-Trumpers, free traders, protectionists, and National Conservatives who, while railing against the dead consensus of fusionism, appear to be building a new fusionist coalition themselves.

The division in the conservative movement is complex. It reflects both political and social changes, geo-political alignments, and cultural, philosophical, theological, and generational shifts. How we got here is … complicated.

The Conservative Movement Was Always Divided

Critics of fusionism speak about the “dead consensus.” Others want to get the band back together, but perhaps the band was always an illusion. More precisely, the conservative movement was predominantly a political coalition more than an intellectual one. Rather than seeing the breakdown of a shared vision, we must admit it has always been a varied one.

The standard shortcut way to describe this old fusionist coalition was as a combination of traditionalists (religious and otherwise); anticommunists; socially conservative, limited-government free marketers; and libertarians. Here were lots of people with irreconcilable differences but who rallied against a common opponent. George Nash documents much of the diversity in his excellent book The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945.

Within and in addition to the main groupings listed above, the conservative movement included evangelicals and fundamentalists, classical liberals, Southern Agrarians, East and West Coast Straussians, Catholics, conservative and Orthodox Jews, paleoconservatives, Chamber of Commerce pro-business people, corporate skeptics, small farmers, large farmers, anti-environmentalists, pro-GMO mono-culture industrial farming people, anti-GMO technology- suspicious conservatives, hunters, natural law Thomists, Buchanan protectionists, free-traders, Second Amendment activists, distributists, Kirkian conservatives, anarcho-capitalists, pro-life activists, Texans, Latin Mass activists, and of course neoconservatives (neocons). But even here, it is important to make distinctions; there were different types of neocons. Michael Novak, for example, was not the same kind of neocon as Bill Kristol. Neocons were first associated with Irving Kristol and leftists “mugged by reality” before they were seen as war hawks. Divisions among this group also played a role in the breakdown of fusionism.

More than a coherent vision of the world, fusionism was an amalgamation of various groups in an electoral compact that shared common foes, including the USSR and the global threat of communism and, domestically, the dominant status quo liberalism that reigned from FDR through LBJ and beyond, the legacy of the New Deal and the Great Society, the sexual and cultural revolutions, democratic socialism, and statism. But once the opposition changed, so did the alliance.

I think it is important to note, however, that there did exist a type of fusionism that was not simply a blending of different views for pragmatic reasons. Among the many camps and groupings, there did develop a “fusionist” philosophy that combined traditionalism, limited government, free markets, and natural law thinking. Here I partially agree with Stephanie Slade of Reason magazine that a fusionist philosophy did exist, but I would argue that it was still just one view among others. What made it stand out and feel dominant was that this fusionist vision was held by some of the most prominent and vocal figures in the movement, including Frank Meyer, who is credited with coining the term (but didn’t like it), and Buckley and Fr. Richard John Neuhaus, the editors of influential conservative magazines. Yet even for many of their followers, this was still a weak grouping of what felt like irreconcilable or least conflicting ideas. For example, support for free markets seemed to contradict the promotion of moral and cultural restraint as well as patriotic adherence to America against growing globalism. But for others, like Buckley, Neuhaus, M. Stanton Evans, and Novak, the fusionist integration was grounded in more than a shaky combination of Hayek’s free market ideas, Whittaker Chamber’s anticommunism, and Russell Kirk’s traditionalism. It also developed out of experience and deeper religious, theological, and philosophical sources like Thomas Aquinas and Catholic social teaching. This is not to say there were no inconsistencies, but it had an internal coherence and mutually reinforcing vision that went deeper than a merely pragmatic alliance against a common opponent. The important point here is that fusionism was both a coherent idea held by a small but vocal group of people as well as a collection of diverse views united against perceived common threats.

The conservative movement was predominantly a political coalition more than an intellectual one.

Victims of Their Own Success?

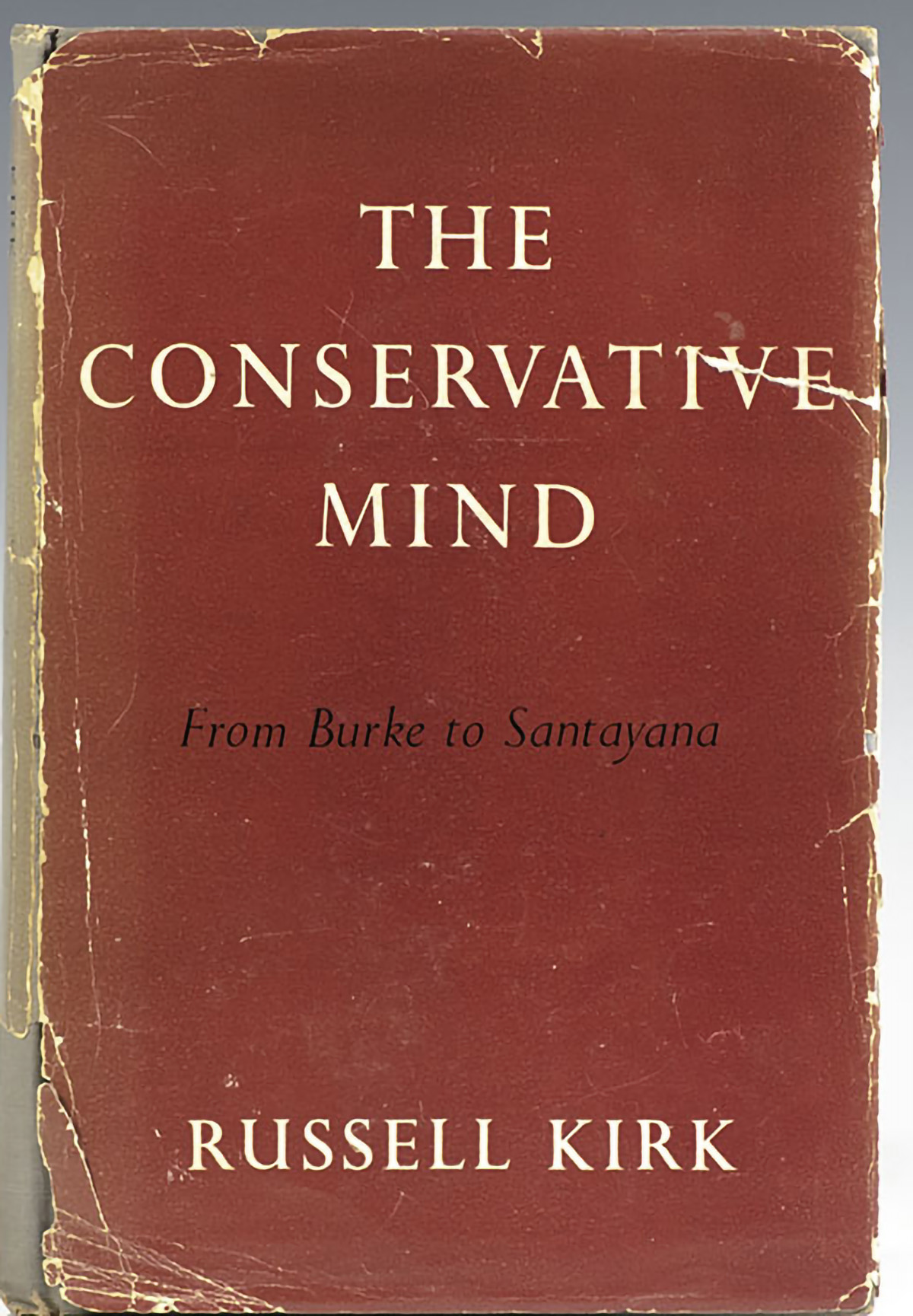

But let’s double-back to the beginning. The modern American conservative movement began in the wilderness in the 1950s and ’60s with, among other events, the publication of Russell Kirk’s The Conservative Mind, Robert Nisbet’s The Quest for Community, Buckley’s God and Man at Yale, and the founding of the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947, the Intercollegiate Studies Institute in 1953, National Review in 1955, the Philadelphia Society in 1964—not to mention the Barry Goldwater campaign for president. The movement’s crescendo was the victory of Ronald Reagan in 1980 and continued to resound through President George H.W. Bush’s administration and into the ’90s with Republican control over the House after 40 years of Democrat domination. These successes also created some changes in the movement. Conservatives were no longer in opposition, and despite small-government rhetoric, the size of government increased under both Reagan and Bush. This, too, revealed division and created disaffected groups that would later seek to break away from the old fusionist coalition.

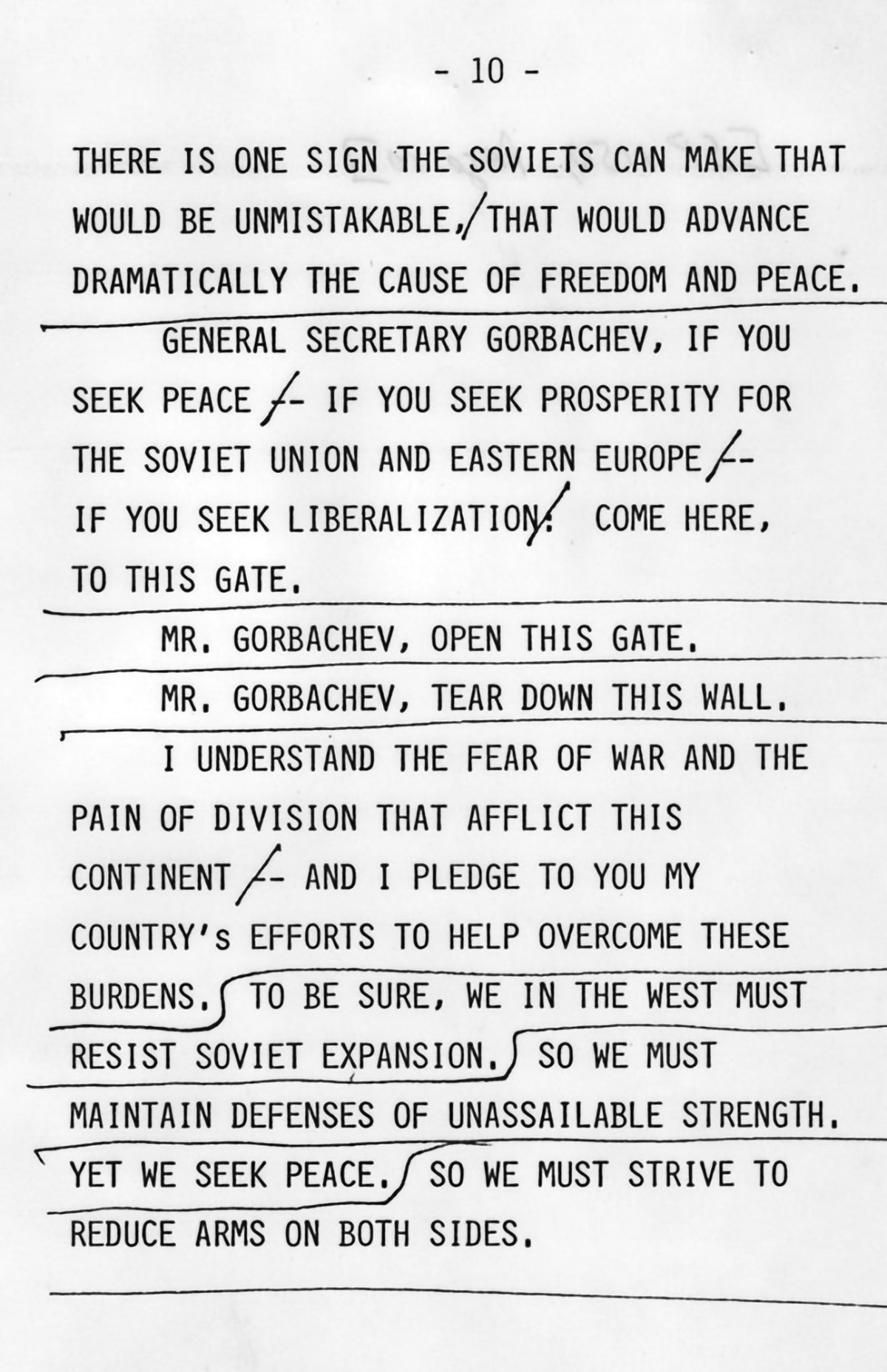

Along with the electoral victories, there was the momentous collapse of the Soviet Union and the failure of communism. Ronald Reagan’s much maligned speeches about the “evil empire” and his call to “tear down this wall,” along with decades of conservative critiques, were vindicated. Contrary to liberal ideas that the Soviet economy would ultimately win out, that communists and socialists were simply misguided liberals, or that appeasement was the only way forward, the fall of the Soviet Union finally revealed the intellectually bankrupt and murderous reality of communism. Conservative ideas, anticommunism, and the free market won out. This victory also meant the opposition crumbled. The conservative alliance lost some of its rationale.

In addition to the fall of the Soviet Union, enthusiasm waned for collectivist polices that had been in vogue in England and the United States for decades. Keynesian economic policy was put on the back burner. There was general support for privatization, liberalization, and globalization. Both Bill Clinton and Tony Blair called themselves New Democrats and New Labor. They spoke positively of free markets, entrepreneurship, business. “The era of big government is over,” claimed Clinton. Globalization and Davos capitalism were now cool. Francis Fukuyama declared the end of history.

All this fractured the fusionist coalition. Conservatives were unsure how to react. Socially liberal pro-business conservatives were happy to join New Democrats and adopt culturally fashionable and even progressive ideas. We see the results of this alliance in corporate social responsibility, DEI, ESG, and what is called “woke capitalism.” Other conservatives following such thinkers as Adam Smith, F.A. Hayek, Nisbet, and Kirk were critical or suspicious of big business, regardless of how “responsible” they claimed to be for various reasons; cronyism, centralizing tendencies, willingness to work hand in hand with big government, etc., were still problems. Then there were those wary of globalization and its impact on American workers, while still others saw free markets as a force for consumerism and moral breakdown. One of the main divisions in the conservative movement today is precisely how to think about business and its role in society.

There was also an error in the conservative movement’s response to the death of socialism. Many erroneously identified socialism solely with its economic dimension instead of recognizing the ideology as a broader social and anthropological vision. As Joseph Ratzinger argued, Marxism was only the radical execution of the spirit that dominated the West, and that after the fall of the Soviet Union, relativism did not die. Instead, he insisted, it combined with the desire for gratification to form a potent mix. Ratzinger, along with Alexander Solzhenitsyn and the Italian philosopher Augusto Del Noce, warned about this morphing of socialism as early as the ’80s. As the world changed and new political, economic, and social problems emerged, many conservatives missed these shifts until it was quite late and continued in a Pyrrhic triumphalism.

When the Soviet Union fell, there was general euphoria that liberal democracy and capitalism had proved victorious. (And to be clear, the euphoria was appropriate. The USSR and other communist nations killed millions of innocents and enslaved several generations of their people.) But something else occurred that is playing out today: the left made temporary peace with markets—and realized they could be used to further their cultural objectives. It was not just in America with the Clintons. José Luis Rodriguez Zapatero, prime minister of Spain from 2004 to 2011, was a prime example: a socialist politician promoting policies attacking the traditional family while lowering corporate tax rates to encourage economic growth.

As the opposition adapted and was recast, conservative blocs continued to unravel, coming to a head during the presidency of George W. Bush with divided views on the Iraq War. Fusionism was on life support by the early 2000s, but the Iraq War killed it for good, and by 2016, with Trump and the resurgence of Buchanan conservatives, alliances had rearranged.

How this will play out in the conservative movement is yet to be seen. Unless a very clear problem akin to something like the Soviet threat arises, the conservative movement will remain fractured for the near future. Deep divisions include: Trumpers vs. Never-Trumpers; conservative debates about abortion and marriage, nationalism, and immigration; increasing worries and critiques about globalization and the free market and its effects on urban and rural communities; and perhaps most unpredicted, criticism of the American founding that until recently most conservatives tended to defend against leftist critique.

Again, we are living in a time of great division. Yet I would argue that this division is needed to work through complex problems and may be more representative of conservatism than the muted electoral alliance of the 20th century. In sum, there was indeed a conservative movement, but while the conservative band was an electoral reality, it was an intellectual illusion.

Reaction Is the New Thinking

Another element that has proved a dividing force of the contemporary conservative movement is the challenge of anti-leftist reactionary thinking that has widened an incoherence within conservatism. Consider, for example, early progressivism. It promoted social engineering, eugenics, the rational planning of those whom Thomas Leonard called “Illiberal Reformers,” and the attendant mechanistic vision that influenced the New Deal, the Great Society, the War on Poverty, and Keynesian, technocratic big-government liberalism. Against all this the conservative movement rallied in an echo of Edmund Burke’s critique of the hyper-rationalism, anti-tradition, anti-organic views of the French revolutionaries and Enlightenment rationalists.

But something happened that created an incoherence in the conservative movement. The ’68 student and hippie movements protested both traditionalism and religion, technocracy and the military industrial complex. As Del Noce and Carlo Lancellotti have argued, when the Age of Aquarius and hippie hopes for a new eschaton failed to materialize in the 1960s and ’70s, the hippies became yuppies. They retained their disdain of family, tradition, religion, and transcendence but embraced technology, technocracy, and material acquisition as a means to happiness. Fred Turner further explored the embrace of techno-utopianism in From Counterculture to Cyberculture. Del Noce explained how everything became an object of trade or manipulation. He called it a shift from the Christian bourgeois with commerce grounded in morality and justice to the “pure bourgeois,” for whom everything is commodified: persons, relationships, sperm, eggs, children—everything is for sale.

Del Noce’s insights are valuable on their own terms for helping understand our current situation. But his analysis also sheds light on the incoherence that existed within the conservative movement and that is now being revealed in some of the divisions today. The student protests and hippie movement led conservatives to support not only tradition but many technocratic, hyper-rationalist solutions, social engineering, Taylorite management techniques, industrial farming, GMOs, and big corporations. Many of these developments became part of a new conservative ethos. But these would have been met with deep skepticism by the likes of Edmund Burke and early conservatives like Nisbet, Kirk, and Christopher Dawson. Whatever happened to the conservative emphasis on free exchange, commutive justice, localism, and subsidiarity?

A simple example I often use to illustrate this is to consider the early conservative reaction to localism, farmers markets, raw milk, and organic movements. Farmers markets are generally unregulated, free, competitive markets filled with small- and medium-size farmers and businesses. But there was, especially 20 years ago, when fusionism was breaking down, a sense among many conservatives that these were just left-wing hippie enterprises. This of course has changed. Many conservatives are now leading voices in skepticism of the industrial medical/pharma complex, but that is part of the point. Changes in society, the rise of “pure bourgeois,” the alliance of government and the medical establishment, and the breakdown of the fusionist compact all contributed to deepening inconsistencies that become more visible and caused further fragmentation among conservatives that persists to this day.

Owning the Libs

Another influence on the current conservative division was the rise of talk radio and conservative cable news, which changed the ethos of the conservative movement—more soundbites, fewer long-form essays and arguments. There was also an emphasis on simplistic narratives that were often just less false than the leftist narratives they were intended to combat. Voices like Rush Limbaugh began as a breath of fresh air and a welcome alternative to establishment and liberal-controlled media and culture. There had been long frustration over monolithic left/liberal dominated universities, media that favored the Democrats and gave short shrift to Republicans, and so on. Some surveys showed that over 90% of professors and journalists identified as liberal. Other voices like Sean Hannity, Laura Ingraham, and Bill O’Reilly also attempted to counter the imbalance with popular critiques and conservative perspectives.

But as time went on, there was the temptation to deliver bombastic and incendiary arguments to “own the libs.” Yes, a substantial audience of listeners and viewers liked this (we all like clear, simple cause-and-effect explanations), but this undermined the conservative ethos of dialogue and wrestling with complexity and tradeoffs. A partisan echo chamber developed on the right as well as an increasing anti-intellectual rejection of nuance. And this was true not only of radio hosts and popular TV commentators—all of us were affected, including academics and scholars.

Everything now has to be simple. Trade-offs are ignored. Free marketers argue that globalization would benefit everyone without seriously considering that some people would be worse off. National Conservatives propose industrial policy and protectionism without wrestling with the dangers of regulatory capture, cronyism, and the negative impacts of protection and a mono-economy on the very people they purport to help. Also unexamined are the erroneous ideas that free trade and capitalism would necessarily make China free or that private entrepreneurs alone invented the smartphone while negating the role of government and military technology—or its corollary, that the government invented the smartphone and national industrial policy could accomplish innovation without the messiness of entrepreneurs.

The world is complex, but we don’t like to hear that. Tough debate is often forsaken, and bickering camps hurl epithets like “free market fundamentalism” and “right-wing socialism.” National Conservatives versus free marketers versus integralists versus libertarians versus strict Constitutionalists versus “the American founding is fundamentally flawed,” and on and on. The coveting of huge numbers of followers on social media has clearly played a role in the dumbing down of complex socio-economic, religious, and cultural issues. Marshall McLuhan’s point about the “medium is the message” and the shaping forces of technology has clearly been proved true. I’ve even heard of leaders of respected publications encouraging people to start fights to get things going. Good argument is one thing, but disingenuous provocation and creating strawmen is another.

Technology Matters

While technological change is by no means the determining factor or most important in understanding the current fractious situation, nevertheless, one of the reasons that conservatism is so divided is that it is incredibly easy to start a magazine, online journal, or even your own blog. In the past, there were only a handful of outlets like National Review, The Freeman, Human Events, the New Criterion, First Things, and one or two others where one could publish conservative ideas. And these magazines had gatekeepers who influenced who and what got published. It is well known that the editor of National Review, William F. Buckley, made sure to exclude from publication members of the John Birch Society and other groups he thought were fringe, immoderate, anti-Semitic, or overly incendiary. But even beyond extreme groups, it was often difficult for many on the right to get published. Now a couple of us could get together, write some essays, record some podcasts and videos, and build a professional-looking website in less than a week—all at a low cost. In short, it’s the Wild West, and there is no one with the authority or influence of Buckley to decide who is part of the “movement.”

There are many benefits to this. Online publishing creates avenues for new ideas and debates. Young and different voices add new perspectives. You don’t have to know anyone to get published anymore—you just have to write decent prose with a compelling argument. This has opened up serious debate about complex topics. It’s no longer necessary to hold to some party line. The ease of publishing creates much more diversity. It also reveals the diversity of thought that was always there.

But there are downsides. Online publishing, combined with social media platforms, doesn’t just encourage and reward good argument; it also rewards bombast and passion without regard to prudence or complexity. I remember as a younger man reading Michael Novak’s Templeton Address, “Awakening from Nihilism,” in First Things or articles by Theodore Dalrymple in New Criterion and hoping someday, in my 50s, after much study and life experience, to write a serious essay like Novak, Russell Hittinger, Peter Berger, or Robert P. George and get published in places of such stature. Today, the need for daily content has watered down the arguments to opinions and hot takes. This requirement for constant content creates a need for lots of writers, many of whom are young and, though often skilled as writers, they are rarely serious thinkers. Partially because they spend so much time generating content, they don’t have time to read and think. And the lack (or failure) of gatekeepers to guide them makes it worse. We have 20- and 30-year-olds opining on how to solve complex global economic issues or resolve geopolitical conflicts.

Online publishing, combined with social media platforms, rewards bombast and passion without regard to prudence or complexity.

In some ways, it’s understandable. More worrying is how it impacts older, seasoned writers. The desire to go viral can overcome a desire for nuance or accuracy. It encourages caricatures of other thinkers and positions. It rewards novelty (or at least apparent novelty) and simplistic albeit attractive intellectual histories that create followers among young readers who do not know better. The lack of gatekeepers has been a boon to letting ideas flow, but now self-described conservative writers can make audacious, silly claims without an editor pulling them back—either because there is none or because the siren song of virality is too alluring to be nuanced. After all, nuance in the “Wild West” just means you’re weak or a squish.

Again, I am not suggesting technological determinism, but it has enabled previously muted voices in the conservative movement to get a hearing they couldn’t get until now, and this has been a major factor in fragmenting “conservatism” for good and bad.

Failure to Deliver

Finally, a key factor that led to real division was warranted frustration: after 70 years of electoral victories at the national, state, local, and presidential levels, plus conservative judicial appointments, lots of think tanks, journals, and policy networks, there grew a strong and understandable sense that the conservative movement had nevertheless failed. Despite political victories and even dominance since the 1980s, conservatives lost the culture in almost every area, from family, marriage, public schooling, and university education to the environment, transgenderism, technology, and free speech. Indeed, with the rise of woke capitalism, Pride month, and all the progressive-activist lobbying, Republicans struggle to influence what used to be their greatest source of support: big business!

But we must ask ourselves a hard question: Are we really different from anyone else? How differently do conservatives act from the rest of culture? What are our marriage rates, childbirth rates, religious attendance, entertainment choices, and so on? As a character asks in the film Katyn, about the Polish resistance to Soviet brutality, what is the big deal that you think differently if you act like everyone else?

Yes, it’s possible to overstate this. There are many wonderful things going on: charter schools, universities, and organizations including the Philadelphia Society that play important roles in creating space for serious conservative debate. And yet, in many ways, we are all still imbibers of big government, big culture, big tech, big education, big medicine, and big entertainment. As Del Noce wrote in 1989, just before his death, Marxism failed in the East as it realized itself in the West. When conservatives, and especially younger conservatives, look at the situation we are in today, they see truth in Chris Arnade’s critique of corrupt elites of the right and left, Tim Carney’s worries about Alienated America, and Michael Anton’s appraisal of Conservative Inc. as the Washington generals that get paid to lose but are happy as long as they keep power.

Socially liberal pro-business conservatives were happy to join New Democrats.

The failure of the conservative movement to deliver on culture, politics, and even many areas of economic policy created division and understandable animosity. I share it. While some of the critiques of the “dead consensus” are mistaken and the diagnoses of our contemporary situation are wrong, these debates are nevertheless positive. Conservatives need to own up to the fact that it’s no longer the ’70s, ’80s, or ’90s. The rote “conservative” answers and approaches from those times are irrelevant at best and harmful at worst. In this sense, division and debate are a positive development. We all cling to incoherent and perhaps irreconcilable positions that we need to wrestle with or let go. Serious debate can revitalize the conservative movement—it can also attract people to it. Conservativism can be principled and rooted in the permanent things and at the same time engage in serious dialogue about our changing world, because dialogue is an affirmation of the logos, of reason and philosophy over ideology.

The crises of our time and the progressive opposition we face make it clear that we must provide more than a compelling political vision. We are in a struggle over not only politics but also civilizational questions: the defense of reason; what it means to be an embodied, embedded person; whether truth can be known; and the meaning and purpose of a society. This means we have to take anthropology seriously, and the complexity of economics, politics, and truth seriously. Our narratives cannot simply be less false. We need to think politically, socially, culturally, and morally. We cannot use Machiavellian means to achieve supposedly Christian ends.

A Parallel Polis

With all that said, I think there is still a pressing need for the two variants of fusionism—both political and philosophical. We need a coalition of diverse views and groups that is still substantive and principled and that can rally against the progressive, transhumanist, and statist left. We need to participate in public life, win elections, while also building what Vaclav Benda called a “parallel polis” and what Nisbet called “a new laissez faire” of associations. We can think and act differently by opting out of big government, big education, big healthcare, big tech, and big culture, and renew American civilization by renewing functional communities. Here we can find common ground and overlap among lots of conservatives, post-liberals, libertarians, traditionalists, free-marketers, agrarians, and followers of Tocqueville and American associational-ism.

We also need to rearticulate and develop a more philosophically coherent “fusionist” vision of limited government, rule of law, support for free competitive markets (with a proper understanding of freedom)—one that also values truth, tradition, the principle of subsidiarity, and our embodied and social nature. This must come from the American experience, but most importantly it must also be rooted in the Jewish and Christian vision of the goodness of being and creation, the dignity of the human person, and the core roles of the family, justice, and the common good that made America possible in the first place.

This essay was adapted from an address given to the Philadelphia Society on March 27, 2021, in Fort Worth, Texas.