Toward the end of the 20th century, historian Mark Noll dilated on the “unobtrusiveness of Lutherans in America.” There was, in what Noll called a “superficial view from the outside,” little in American Lutheranism that seemed “newsworthy.” To those in the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS), such an assessment would probably not have constituted news. Although the longstanding and sometimes self-perpetuated stereotype of the LCMS as a midwestern church overwhelmingly composed of head-down, mind-their-own-business immigrant farmers was of course never entirely accurate, neither was it wholly mistaken. Reared on Martin Luther’s warning against a “theology of glory”—the belief that worldly prestige or success is confirmation of standing in God’s favor—the clergy and laity of the LCMS would likely have accepted “unobtrusive” as a fair, even complimentary, evaluation of their place in American society.

Revisiting the Concordia Seminary controversy 50 years later is to realize that sometimes neither politics nor theology is key to preserving orthodoxy.

Which made it all the more shocking when, between 1969 and 1974, such an un-newsworthy church was very much in the news. It featured regularly in religious periodicals like Christianity Today, consistently made headlines in the New York Times, and was being discussed by Walter Cronkite on the CBS Evening News. When the controversy that courted such attention reached its peak a half-century ago this year—when 85% of the 700 students at its chief seminary withdrew and 90% of the same seminary’s faculty were fired—media referred to it as the “climax to the top religious news story of the past few years.”

What exactly was that controversy, and what made it so embarrassingly newsworthy? The answers to those questions have remained in dispute over the intervening five decades. For many in the church, the conflict was nothing other than a “Battle for the Bible,” the early 20th-century fundamentalist-modernist controversy restaged in Lutheran vestments—but rewritten with a happy ending. The march through the institutions that had transformed the mainline Protestant churches was halted and reversed; liberalism was routed and conservatives maintained control of the institutions. In this telling, the conflict was always and only theological.

Yet others have denied that doctrine was the true engine of conflict. There was no theological division in the Missouri Synod, they argue, or at least none significant enough to warrant charges of heterodoxy, threats of discipline, and eventual schism. Rather, the controversy was primarily political. In this narrative, not only were many of the divisive issues political in nature, but so too were the tactics and goals. Far from maintaining the status quo, conservatives introduced novelty with their unchurchmanlike adoption of secular political maneuvers—campaigning for church offices, packing committees with partisan allies, and exploiting media to organize the base. Expressed doctrinal concerns were merely pretext for a seizure of power. The whole affair is therefore best described as a “takeover” that issued in a “purge.”

Whether substantive theological differences or cynical political machinations—or both—drove the controversy of the early 1970s, what has always remained beyond dispute is that its point of focus was Concordia Seminary in St. Louis.

Clouds on the Seminary’s Horizon

In the course of walking a freshly hired professor around Concordia Seminary in 1958, LCMS president John Behnken cautioned him that not all was as idyllic as the Gothic buildings and shaded lawns might suggest. The institution faced “serious problems,” he warned; there were “dark clouds on the horizon.” It is perhaps no coincidence that, though the seminary had been founded more than a century previously, these remarks were offered by the first American-born president of the church body that owned and operated it. Behnken himself was a symbol of the Americanization that was one source of his concerns.

Established in the 19th century by refugees from wayward and oppressive European state churches, the LCMS had largely retained its Germanic language and culture—insulating itself from many trends influencing American churches—until nativist hostilities attendant on two World Wars made a degree of assimilation seem only prudent. A generation later, that begrudgingly made decision might have appeared (if one were tempted by a theology of glory) divinely approved. Between 1935 and 1962, the years of Behnken’s presidency, the church had nearly tripled in size and was the largest Lutheran body in America, oversaw the largest Protestant school system in the nation, and governed 10 undergraduate colleges. Its flagship seminary regularly sent graduates to doctoral programs at the Ivies and abroad, and counted Martin Marty, Jaroslav Pelikan, and Richard John Neuhaus among recent alumni.

But—as the eventual exodus of those esteemed alumni from the LCMS might suggest—Behnken was not wrong to fear that such rosy anecdotes obscured real, and growing, fault lines. Indeed, two further events of the same year would send the first tremors through the broader church.

In February of 1958, New Testament professor Martin Scharlemann presented a short paper for faculty discussion in which he bluntly stated, “The book of God’s truth contains errors.” Pressing the point, he made clear that he was taking direct issue with the Brief Statement of the Doctrinal Position of the Missouri Synod formally adopted at the Synod’s 1932 National Convention and regularly reaffirmed thereafter. According to that document, “Since the Holy Scriptures are the Word of God, it goes without saying that they contain no errors or contradictions.” Although originally presented behind closed doors, the sentiments of Scharlemann and other seminary faculty were not exactly a closely held secret, as evidenced by the second significant event of 1958.

In that year, Herman Otten, a bright but pugnacious student, brought accusations directly to President Behnken that faculty were teaching contrary to LCMS doctrine. The faculty was incensed by the charges but, rather than rebut them, took Otten to task on procedural grounds. They complained that classroom teaching was private and so students had no right to publicize its content; more persuasively, they argued that Otten erred in not bringing his concerns directly to the faculty before “telling it to the church” (cf. Matt. 18:15–17). He conceded the second point and apologized for the manner in which he made the accusations; he would not, however, retract their substance. The faculty therefore informed him that he would not be certified for ordination upon graduation.

Denied pastoral status in the LCMS, and so largely beyond the reach of ecclesiastical oversight, Otten devoted his considerable energy to the creation of Lutheran News (soon renamed Christian News), a confrontational weekly newspaper that immediately became the most widely circulated—and consistently denounced—source of news, polemic, and innuendo regarding the perceived infiltration of liberalism within the LCMS, not least at Concordia Seminary.

But Otten could also operate in less confrontational ways; he was reportedly the means by which Scharlemann’s unpublished paper eventually landed on the desk of President Behnken, confirming rumors that had swirled since its original presentation. Because it was clearly at odds with the position articulated by the LCMS, delegates to the 1962 National Convention were presented with a resolution to strip Scharlemann of his professorship. Before action was taken, however, Scharlemann addressed the convention. Walking back his previous comments, he confessed the Scriptures to be “utterly truthful, infallible and completely without error.” He apologized for being a cause of unrest and asked the forgiveness of Synod. Delegates granted it by an overwhelming vote of 650 to 17, and Scharlemann continued at Concordia for another 20 years.

Despite the joy expressed at the prodigal’s return, though, there remained lingering doubts that Scharlemann had been a single bad apple. Through the next decade, Herman Otten did his best to encourage those doubts; the seminary faculty, on the other hand, did less than their best to discourage them. So too did Oliver Harms, voted in as Behnken’s successor at the same 1962 convention.

Tietjen insisted that a seminary requires ‘a diversity of viewpoints, even conflicts of viewpoints.’

Unlike Behnken, Harms was unconvinced of “serious problems” at the seminary. At the 1965 convention, he lamented the “public accusations” and “negative criticisms” leveled at the faculty and waved away calls for an enquiry into their teaching. Assuming clearer communication would assuage concerns, though, Harms did encourage the faculty to publicly rebut rumors that some of them, for example, denied the factuality of certain biblical miracles. The faculty responded instead by questioning the usefulness of terms like “factuality,” and the seminary’s president, Alfred Feuerbringer, could only weakly assure Harms that “no member of the faculty holds that the Bible contains error in the moral sense of the term.” Satisfied, Harms again at the 1967 convention decried “accusation and slander,” along with “divisiveness and dissension … over matters that are not part of the Gospel.”

A Traditional vs. an Alien Theology

Through the second half of the 1960s, it therefore became increasingly clear to both traditional and progressive factions that Harms was the seminary’s most effective defender. If the Synod were to get a frank review of faculty teaching, believed the former, Harms would have to be replaced as LCMS president. If Harms were indeed ousted, the latter believed, the seminary must acquire an even more amenable and assertive head.

Both changes came to pass two years later. Rallied in no small part by the drumbeat of Christian News, delegates to the 1969 National Convention did what had long been considered unimaginable: they voted a sitting president out of office. The replacement of Harms by Otten-backed J.A.O. (Jack) Preus II seemed to sanction a more vigorous approach to perceived problems at Concordia. Anticipating the possibility of synodical leadership change, though, Feuerbringer had already announced his retirement as seminary president, allowing his replacement to be elected prior to the convention (ensuring that, were a more conservative synodical president there elected, he would have no say in determining the seminary’s leadership). His successor, John Tietjen, came into the office from the public relations office of the interdenominational Lutheran Council in the U.S.A. If, as Harms professed to believe, a lack of clear communication was the root cause of recent turmoil, Tietjen’s expertise would surely be pacifying.

It was not to be. Indeed, Tietjen quickly created further confusion with apparently mixed messages. He insisted that a seminary requires “a diversity of viewpoints, even conflicts of viewpoints,” while also insisting that “rumors of division” among faculty “are not true.” But in February 1970, only a month after making the latter assertion, he participated in a faculty meeting to discuss a multipage list of theological points on which professors were at odds, admitting that public awareness of such division would be “disastrous.”

The suspicions of many had already been confirmed a month earlier, however, when three professors signed on to a publicly distributed Call to Openness and Trust. Despite the title, its blunt denial that “the question of factual error in the Bible” should have any bearing on LCMS membership inspired little trust in the seminary. Finally, in early April, none other than the prodigal professor Martin Scharlemann wrote to Preus that students were complaining of a “theological schizophrenia” evident in classroom teaching, and encouraged an official review of the doctrines held by the faculty. Less than two weeks later, Preus announced he would do just that.

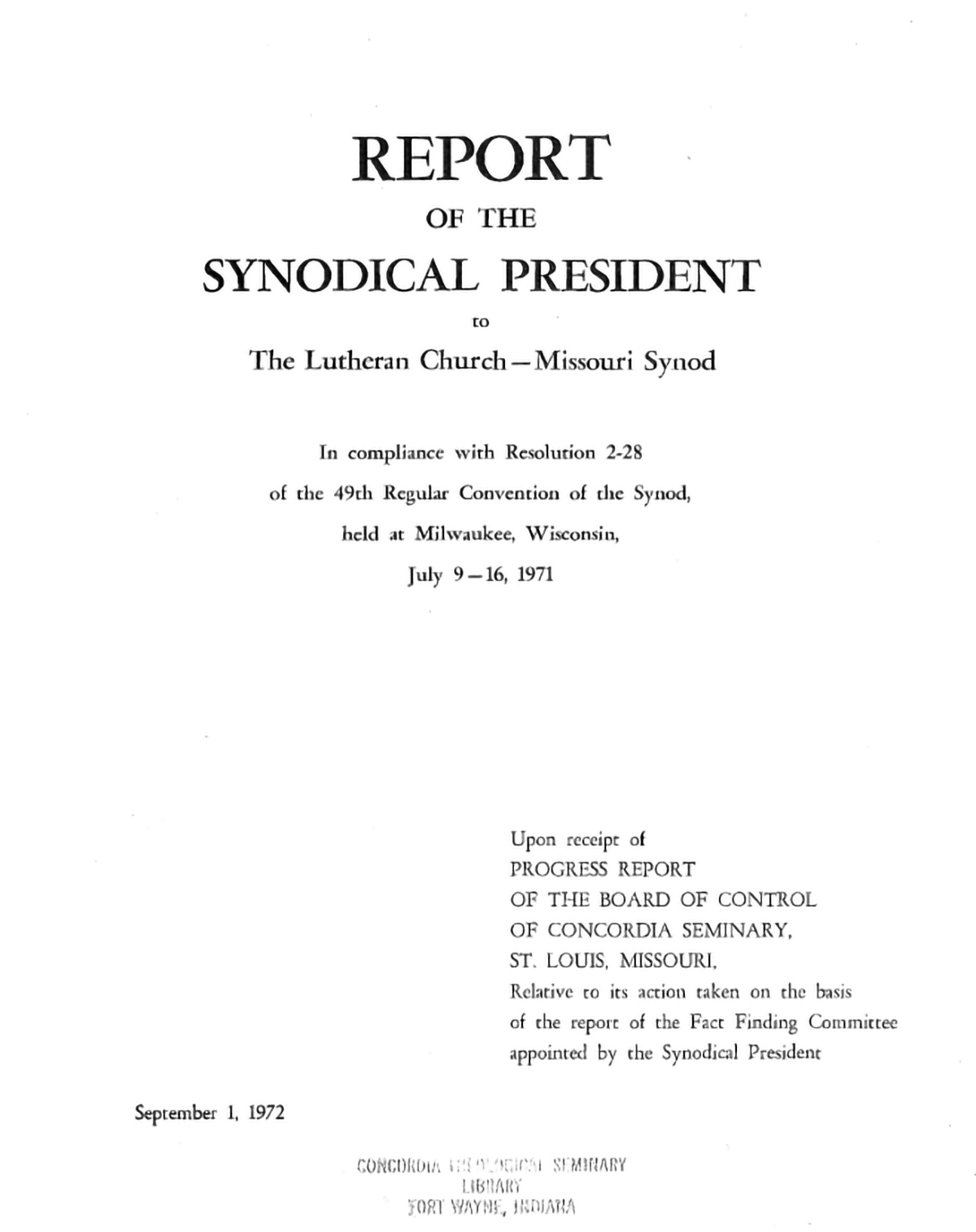

His appointed “Fact Finding Committee” interviewed all Concordia professors and reviewed their publications and presentations. Professors were allowed the opportunity to review, amend, and supplement transcribed interviews. Tietjen himself attended all interviews and, with a single exception, raised no objections to the procedures. Indeed, despite expressing his “regret that Dr. Preus had chosen to dignify the accusations of the seminary by conducting an investigation,” Tietjen professed to welcome it as an opportunity to “demonstrate how truly Lutheran we are.” It was of course inevitable, though, that some would characterize the committee’s work as an “inquisition” and the work of “frustrated dictators.” As interviews took place between December 1970 and March 1971, seminary faculty increasingly voiced the same opinion. In January, Tietjen publicly criticized the committee’s work as “unscriptural, unethical, [and] divisive,” announcing that the faculty would continue to cooperate “only under protest.”

None were surprised, then, that the committee’s activity became a heated topic of debate at the 1971 National Convention. But if the election of Preus two years earlier had been read as a mandate to investigate the seminary, the 1971 convention made this explicit. Delegates affirmed the committee’s constitutionality and commended Preus for his “pastoral concern for doctrinal unity and purity” in creating it. He read the signs and acted accordingly, requesting fellow conservative Ralph Bohlmann to draft a Statement of Scriptural and Confessional Principles. The document’s intended purpose, he explained, was to provide basic criteria by which the seminary board might evaluate the summary report of the Fact Finding Committee. In addition to forwarding the Statement to the board, however, in March of 1972, Preus released its text to all congregations of the LCMS.

The faculty’s reaction was immediate, condemning the Statement as “unscriptural,” “unethical,” and having “a spirit alien to Lutheran confessional theology”—an unintentionally revealing assessment, since the Statement itself largely relied on previously adopted doctrinal resolutions of the LCMS. Indeed, even an outside observer critical of its theological content would concede that it contained “nothing even slightly innovative,” but was entirely “traditional, and never retracted solid Missourianism.”

But before the next National Convention could render judgment on whether the Statement’s theology was “traditional” or “alien” to the LCMS, Preus would make one more move to influence its outcome. The Fact Finding Committee had presented its report to both him and the seminary board in June of 1971, but its content had never been made public. Throughout the following year, Concordia faculty loudly complained that the report misrepresented their teaching. Whether such complaints were warranted, though, was impossible for the wider church to determine without knowledge of its content. Moreover, since the report merely summarized the committee’s findings, even if publicized, how would Synod members judge the accuracy of those summaries? In September, Preus solved both problems by distributing his own Report of the Synodical President. Rather than merely including the committee’s original summations, however, it provided lengthy excerpts from the faculty interviews and writings that had informed them.

This “Blue Book,” so called for the color of its cover, landed like a bomb. As Tietjen would later admit, “We realized full well that for us the BB was a disaster.” He thus retreated to allegations that the investigation had been prejudicial and unfair. Most significantly, he doubled down more explicitly on his remark about a spirit “alien” to Lutheranism. In a document distributed to all LCMS clergy, he asserted that “the theology which lies behind the inquiry and the report, by whose standard the theology of the faculty was measured, is unLutheran.”

Almost certainly Tietjen—who regularly portrayed critics as “more fundamentalistic than Lutheran”—believed this to be true. Just as certainly, saying so out loud was an unforced error. For more than a decade, the faculty’s contention was, in effect, “We’re Lutheran too.” In their responses to both the Statement and the Blue Book, Tietjen and the faculty now appeared to be saying, “We’re Lutheran, and you’re not.” The unstated implication was that both camps within the LCMS now agreed that the Synod was afflicted by real theological differences, and that only one party could be deemed faithfully Lutheran. It would fall to delegates at the next convention to determine which party that was.

Ousting the Sem’s President

The 1973 reelection of Jack Preus by a 2-to-1 margin was an early indication of the way voting would go. By a similar margin the convention reaffirmed Synod’s right to adopt doctrinal statements “in accord with the Scriptures and the pattern of doctrine set forth in the Lutheran Symbols,” and to make such statements “binding upon all its members.” The Statement of Scriptural and Confessional Principles was itself deemed to be “Scriptural and in accord with the Lutheran Confessions,” and to express “the Synod’s position on current doctrinal issues”; it was thus formally adopted as a binding doctrinal statement.

Having approved the Statement, it was a foregone conclusion that the alternate theology embraced by the Concordia faculty would be judged “false doctrine running counter to the Holy Scriptures, the Lutheran Confessions, and the synodical stance.” Such doctrine, the adopted resolution concluded with a quotation from the Lutheran Confessions, “cannot be tolerated in the church of God, much less excused and defended.” The seminary board, with a newly elected conservative majority, was directed to take appropriate action.

Lack of time prevented the convention’s consideration of a more specific resolution to remove John Tietjen from the seminary presidency. Shortly thereafter, though, two congregational pastors brought formal charges against him for having “allowed and fostered the teaching and dissemination of doctrine contrary to the Scripture and the Synod’s historical confessional stance.” The board accordingly announced on January 21, 1974, that Tietjen would be suspended (with full pay and benefits continuing) until the case brought against him could be resolved.

Tietjen addressed seminary students the following morning, denouncing the “moral bankruptcy” of Preus and the seminary board, and what he called “collusion” between them and his accusers. The student body immediately declared a moratorium on class attendance; the same day, the faculty majority announce a similar moratorium on classroom teaching. As the headline in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch explained, “Majority at Concordia Suspend Themselves.”

The ensuing stalemate dragged on for a month, until the long drama finally climaxed on February 19. On that date, the board had already announced, any faculty who had not resumed teaching duties would be dismissed for breach of contract. Rather than return to classrooms on that day, faculty and students staged a theatrical “funeral” for Concordia. While news cameras rolled, bells were tolled and white crosses were planted in the campus quadrangle. After reading the biblical account of Israel’s exodus from Egypt, professors and students processed off campus to establish their own “Seminary in Exile” (Seminex).

The student walkout and simultaneous firing of most faculty brought to a crescendo 15 years of conflict concerning the seminary, now reduced from 50 faculty members to five, and from 700 students to fewer than 100. The repercussions of the controversy would of course continue for years. One immediate consequence, though, merits brief mention because it brings the affair nearly full circle. Declaring that Seminex was the “real” Concordia existing in exile, faculty had also convinced students that certification for ordination in the LCMS would be unproblematic. But as they well knew from their own treatment of Herman Otten at the controversy’s beginning, such certification was the prerogative of Synod’s recognized seminaries. Otten no doubt relished seeing his old antagonists hoisted on their own petard.

Chairman Jao?

But what had it all been about, this civil war over a seminary? These skeletal outline of events clearly emphasizes the theological nature of the controversy. But there is no question that it was deeply enmeshed with politics throughout, evident not least in the tawdry tactics employed by partisans across the divide. Extra-synodical interest groups proliferated, clandestine meetings were held, lists of approved candidates for office were distributed, language was manipulated, media were exploited.

Criticism of the conservative faction has, with warrant, made much of Otten’s incredibly effective but ethically dubious journalism—printing, for example, the content of private correspondence or secretly recorded conversations. Much has likewise been made of Preus’ political maneuvering, often, though never overtly, in concert with Otten. The preludes to the 1971 and 1973 National Conventions provide particularly egregious examples. To prevent undue partisan pressure upon delegates, Preus insisted that their names not be released prior to the conventions, “except upon authorization of President Preus.” He then promptly, but privately, authorized their release to Otten.

Faculty complained that inerrancy had become a shibboleth and that it was not found in the Lutheran Confessions.

Even without the cloak-and-dagger, though, Preus, as Synod president, wielded immense control over church appointments and proceedings, especially those of the Synod’s regular conventions. Speaking of the committee that brought forward the conclusive 1973 resolutions on seminary matters, he later recalled, “that was an absolute 100% conservative committee.” Of course it was; he’d had the prerogative of appointing its members. The possession of such power led Newsweek to describe Preus as a “Lutheran Pope.” Syndicated columnist Lester Kinsolving upped the ante, employing Preus’ initials to dub him “Chairman Jao.”

Whatever one makes of Preus’ political devices, though, two things deserve note. The first is that a great deal of the power he wielded had been given him by the very faction complaining most loudly about its use. Feeling increasingly thwarted by the lay-populism made possible by the LCMS’s congregational polity and exploited by Otten’s muckraking, progressives in the mid-1960s had moved to reduce the influence of laity and congregations and to increase that of the bureaucracy. Resolutions adopted shortly before Preus’ election, for example, stripped laity of the right to submit overtures to conventions and gave Synod presidents absolute power of deciding which overtures would come to delegates as resolutions. If the Synod, urged on by its liberal elements, wanted its presidents to wield such unchecked power, well, who was Preus to disappoint them?

Also, however poorly politicking reflected on Jack Preus and his allies, it reflected equally poorly on John Tietjen and his. Faculty retaliation against Otten’s whistle-blowing and the irregular election of Tietjen have already been mentioned. Tietjen’s own power plays were especially evident in his treatment of those faculty in the traditional minority. To note only one example, within hours of Martin Scharlemann’s having recommended that Preus investigate the seminary (in a letter he copied also to Tietjen), Tietjen announced a special faculty meeting for the following week—while Scharlemann was away on duty as a military chaplain. Though no agenda was advertised, the only item of business was a vote to censure Scharlemann, who then received a follow-up letter with threats of discipline and accusations of insubordination for not being present at the meeting.

In sum, neither camp was above bare-knuckle politics. However much both parties denounced the other’s stooping to such tactics, each convinced itself that theological ends justified political means. In other words, though the conflict was unquestionably political, it was never about politics. Tietjen was no less clear about this than was Preus. He openly expressed what he called “grave misgivings about the doctrinal position of our adversaries,” which he insisted was “something different from what was in the Lutheran Confessions.”

Not only did both parties agree that the conflict was fundamentally theological; they agreed even on the specific point of theological dispute. At a May 1972 meeting of Preus with Concordia faculty, all agreed that “the basic issue is the relationship between the Scriptures and the Gospel,” and more specifically, “whether the Scriptures are the norm of our faith and life or whether the Gospel alone is that norm.” This being the case, it was rather strange that Tietjen and the faculty majority insisted it was their opponents who were “unLutheran.” The Lutheran Confessions are quite explicit that the Scriptures are “the only true standard by which all teachers and doctrines are to be judged.” The seminary president and faculty, on the other hand, declared that “the Gospel gives the Scriptures their normative character, not vice versa.”

Equally strange in this light is Tietjen’s open acknowledgement that it was indeed his party’s position that had changed over time. He would later write, for example, “I did not appreciate what I thought was less than candor in the seminary’s repeated claims that nothing had really changed in the CS [Concordia Seminary] teaching. I resented the efforts to demonstrate that what was happening at CS was really the ‘old’ Missouri Synod after all.”

When the formation of the AELC provided congregations the opportunity to vote with their feet, 96% remained with the LCMS.

The earlier remarks of Alfred Feuerbringer—implicitly conceding that faculty members believed the Bible contained errors in some non-moral sense—and Oliver Harms—declaring this to be fine so long as the point at issue was “not part of the Gospel”—offer clear, if subtle, indications of the changes that were taking place with respect to the traditional confession of Scripture’s inerrancy. Faculty complained that the term had become a shibboleth and that it was not found in the Lutheran Confessions (a bit of pedantry that willfully ignored those Confessions’ insistence that the Scriptures are God’s “pure, infallible, and unalterable word” and that “God’s word cannot err”). As Feuerbringer and Harms clearly understood, the concept of inerrancy was only acceptable, at least to some faculty, in a strictly qualified sense, with reference only to those portions of Scripture deemed “part of the Gospel.”

Faculty statements, however, made evident just how expansive that qualification could be. Some cast doubt on the virgin birth of Jesus, for instance, while more than one raised questions even about Christ’s resurrection. Dr. Walter Bartling, for instance, told students that “it made no difference to his faith whether or not Jesus’ body physically rose from the dead”; speaking on another occasion to fellow pastors, he declared, “I have problems with the virgin birth, real presence [of Christ in the Sacrament of the Altar], bodily resurrection. … I can’t bear the burden of Scriptural infallibility.”

To be sure, such extremes were not embraced by most faculty members. Indeed, some in the majority could concede even to Tietjen that “the other side does have a point. How much Gospel do you have left if you don’t have a historical event on which you ground it? Can we proclaim Jesus as the divine physician if the miracles of healing didn’t happen?” None the less, the faculty majority was adamant that even the most radical views were not disqualifying for a Lutheran, a Lutheran pastor, or even a teacher of the next generation of Lutheran clergy. The broader church disagreed. Even while Richard John Neuhaus allied with the progressives and eventually departed the Synod with them, the majority of LCMS members intuitively anticipated his later formulated “law”: “Where orthodoxy is optional, orthodoxy will sooner or later be proscribed.” Nor did subsequent events give them cause to reconsider.

When it became evident that Seminex would not be recognized as a seminary of the LCMS, faculty and sympathizers in 1976 organized an independent denomination, the American Evangelical Lutheran Church (AELC). A decade later, their merger with two other Lutheran bodies created the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), a denomination perhaps most familiar to outsiders for its vulgar superstar “pastrix” Nadia Bolz-Weber and her “vagina project” (in which donated purity rings were melted down to form a sculpted vagina). Or perhaps it is best known for the 2023 headlines made by one of its congregations liturgically reciting the “Sparkle Creed,” in which was confessed belief in a “non-binary God whose pronouns are plural” and a Jesus who “had two dads” and “wore a fabulous cloak.” Then again, maybe it’s for the intersectional dust-up involving transgender bishop Megan Rohrer, recently removed from office following accusations of “racist words and actions” but who also sued the denomination for alleged gender discrimination.

Would such have been the fate of the LCMS if Concordia’s faculty majority and student acolytes had remained? Offering confident answers to counterfactual questions is a fool’s errand, but two things might at least be noted about the Seminex trajectory. The first is that many of the former LCMS pastors and professors who entered the ELCA were not simply passive observers of that denomination’s moral and theological radicalization. More often they spearheaded it. As their new colleagues observed already in the 1980s, “they became advocates of progressive agendas in their new ecclesial setting,” and “when the umbilical cord was cut those dissidents tended to run amok.” Also, as such remarks suggest, here again one might note ironic similarities between the progressives and their original nemesis Herman Otten. Once free of LCMS oversight and the attendant necessity of prudence and circumspection, all bets were off.

Whether the ELCA’s trajectory would have been the LCMS’s if the faculty majority had gotten its way, it can at least be said that their departure made possible the maintenance of—or return to—traditional Missouri Synod orthodoxy. When the formation of the AELC provided congregations the opportunity to vote with their feet, 96% remained with the LCMS. A similar vote of confidence for Concordia itself proved the seminary’s mock funeral premature. Accreditation was maintained, the faculty was quickly rebuilt, and already by the 1980–81 academic year, enrollment was back up to more than 700 students.

When Your Opponents Walk Away

Given the typical pattern of American church schisms, in which the liberal party gains control of denominational institutions and conservatives split off to form new ones, one might assume there are some practical lessons that might be learned from the contrary LCMS experience. Frankly, though, it’s not at all clear what these might be. Though a theology of glory might still tempt some to speak proudly of routing the forces of liberalization and saving orthodoxy, LCMS traditionalists did not in the final analysis maintain control of Concordia because they had the better arguments, because their messaging was more effective, or even because their politics were more Machiavellian. They “won” because their opponents simply walked away.

They traditionalists ‘won’ because their opponents simply walked away.

For all their disagreements, this at least was a point on which John Tietjen and Jack Preus would come to consensus. Tietjen later admitted that the walkout was a tactical blunder, that the faculty should have stayed and forced the administration to bring formal charges against each professor individually: “It would have been much more difficult for them to bring off.” By Preus’ own admission, it would likely have been impossible. The collective will to prosecute dozens of high-publicity heresy trials simply didn’t exist. Had the faculty and students only returned to their classrooms, he remarked, “They could have broken the back of the Synod.”

The conclusion is sobering, but almost certainly correct. Perhaps, then, there are no practical lessons to be learned, only eternal truths to be remembered. Not least that “the Lord is merciful and gracious, slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love. He will not always chide, nor will he keep his anger forever. He does not deal with us according to our sins, nor repay us according to our iniquities” (Ps. 103:8, 10). Thanks be to God.