Amid the rise of the nones and the implosion of church attendance, concerned Christians have offered a myriad of explanations and recommendations for what must be done to repair the wreckage of our culture. They may exhort us to wage cultural war against the apparent dying of the light, embark on various plans of cultural care that might draw in the lost, or retreat from the public square altogether for the purpose of spiritual fortification. But all such suggestions share a common sense that the reputation of Christianity in the U.S.A. is in a bad state.

Fight or flight? Christians looking to the early church may find another way of engaging and surviving in a culture gone mad.

By Stephen O. Presley

(Eerdmans, 2024)

Studies may (or may not) show that men think about the Roman Empire once a day, but the resonances between the Roman world and ours at least appear to grow more profound. We seem to live in “dread latter days” akin to those Walker Percy described in Love in the Ruins, where everything is falling apart. Corruption in high places and loss of public confidence in the laws and traditions of our polity abound. So, too, does a public anti-theology that demands entrance into every public space: How else to explain the “progressive” insistence that every public library in America be a place where transgenderism is celebrated; that elusive if not nonsensical concepts like equity supplant the long traditions and customs that gave us a tolerably clear notion of justice; or the complete rejection of conscience as previous generations understood it? A repaganizing of our public culture proceeds, with its own distinctive public cults and idols. Roman history may not be repeating, but we can at least read the rhymes.

Rome was a place, as Ferdinand Mount notes, where you “could believe in anything or nothing” if it did not disrespect the civic region. Christian belief was decidedly in conflict with the dominant Roman culture because of its insistence on one God and his law. It is easy to overestimate these comparisons to Rome, but Christians anxious about our faith’s loss of status have generally not looked to the early church for inspiration for how we might cope with—or even thrive under—these circumstances.

In Cultural Sanctification: Engaging the World Like the Early Church, church historian Stephen O. Presley aims to remedy this oversight. He does so in recognition that the situation appears quite dire:

We are no longer living in a modern world where Christianity is intellectually suspect but morally acceptable. We are in a postmodern world where Christianity is rejected as morally bankrupt (and most of the time still intellectually suspect). … While many moral expressions are applauded in the public square, traditional Christian morality is not often discussed in polite company.

Presley looks to the early church because these conditions bear some resemblance to that of the Christians living in the late Roman Empire, a time when the church grew even amid persecution, scorn, and dismissal by most Romans. The early church offers distinctive lessons for the present, he argues, and as an example of how to embark upon the book’s eponymous “cultural sanctification.” Christians should neither assimilate to the cultures in which they live nor exile themselves from public life. Instead, we should pursue a manner of engaging with culture that “neither repeats Benedict nor crowns Charlemagne.”

Presley develops his account through thematic chapters that address major areas of life in the early church and our own time. The first of these concerns identity, which especially in this era of identitarian idolatry seems apt: the dominant culture tends to insist that identity is the master category through which we engage with others. To begin with, this denies that the world (or for that matter the bodies) we inhabit have any authority or reality. What remains is the limitlessly creative—and destructive—sense of self-invented identity. Against this confusion, Presley reminds Christians that they are called “to put on the new self, created after the likeness of God in true righteousness and holiness” (Eph. 4:24) and that believers have good reason to realize their identity in Christ rather than in culture.

The early church was quick to show hospitality to newcomers but very slow to admit them into the body of Christ.

The early church was quick to show hospitality to and teach newcomers, but very slow to admit them into the body of Christ. The church prayed for the conversion of their neighbors but was focused on the patient cultivation of those “who were willing to join their community and conform their lives after the teachings of the church.” Focused on teaching what they called “the rule of faith,” which offered “an essential summary of the church’s main theological commitments and presaged the creeds that would develop later,” the early church was defined by the long, challenging work of catechesis. The rule served as the church confessional standard to which members must adhere, but also gave God’s people a basis on which to order their lives, “so that whether surrounded by ancient stoics or modern secularists, this rule orders reality.”

Without this fuller sort of conversion the early church sought, Presley thinks any attempt by Christians to sanctify our culture will fail: “We are often concerned with how to respond to culture without considering the very basis upon which that response must proceed.” This leads to outreach efforts and other forms of programming that place the seeker at the center of many churches’ efforts at evangelism. The difficulty here is that these efforts do not begin with doctrine but with various experiences that mimic secular culture rather than stand apart from it through being distinctively Christian.

The modern church, Presley argues, has placed far too much emphasis on the moment of conversion and the practice of revival. He argues that the model of revivals, especially in their most recent versions, fail to grasp that, for most people in the U.S. and other western countries, “revivalism assumes that the reigning cultural structures are Christian, and that a dead Christendom can be brought back to life.” Today no church can assume that new believers have any knowledge of scripture or doctrine—and speedy growth is likely to result in new Christians that are very ill-equipped to answer challenges to their faith.

Christians should stand apart from secular citizens in their belief in providence.

Throughout this discussion, Presley implies that efforts to restore the public forms of Christianity without conveying the substance of the faith are doomed to failure. Sudden revivals, too, are unlikely to return us to a Christian public culture. Christendom, he emphasizes, was created not simply by persuading the Roman elite to embrace Christian observance but by building a body of believers deeply committed to the faith: “There is no Christian cultural sanctification, either in the ancient world or today, without Christianconfession.”

Cultural Sanctification is not a work of political theology, and Presley does not develop comprehensive notions about how Christians ought to engage in political life today. Instead, he asks variations on this question: What would it be like if Christians today were known for the same sort of citizenship as members of the early church were? He tells us that three assumptions formed the core of the early church’s approach to politics: “a firm conviction in divine transcendence and providence, a belief that God granted political authority to certain earthly rulers, and an active citizenship that proceeded from a political dualism.”

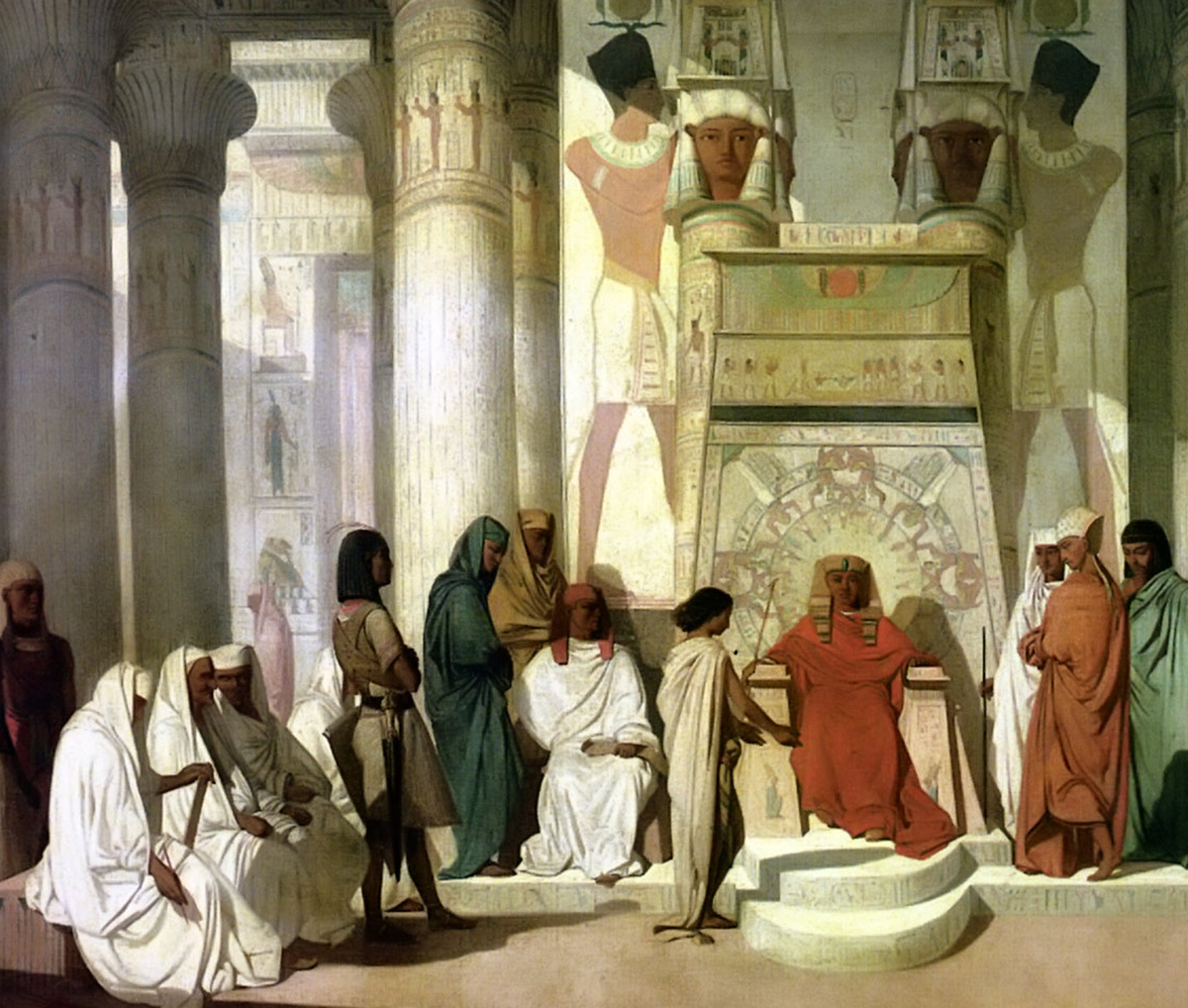

Christians should certainly stand apart from secular citizens in their belief in providence. This should give us confidence that, even if our own circumstances are painful or difficult, we need not fear the ultimate outcome of history. Presley emphasizes what this meant for the early church in terms of its relations to power: “When Joseph or Daniel found themselves in a foreign land ruled by a pagan king, they did not sit around complaining; they lived virtuously and worked within the structures of the civil authority to become leaders worthy of respect.” Moreover, “to the early church, the state was essential to the work of God and the unfolding of God’s redemption. The church was not rebellious or cynical toward the state and agreed with its pagan neighbors that those who rebel against the king or dissolve public order should be justly punished.” Governments are instituted for our good. The goal is to balance judgment against the state’s excesses while respecting the necessity and goodness of political power.

The principal lessons Presley thinks we can learn from the early church have to do with respecting civil authority. He suspects that Christians have too generally lapsed into dishonorable forms of critique, that they too begrudgingly pay their taxes and frequently adopt an unbiblical view of the state as an evil to be rejected. Here, too, the early church can guide us: it eschewed any effort to reject secular political authority—rendering unto Ceaser—or to “meld religion and the state as theonomy or integralism.”

Presley says little more on this point, but his rejection of attempting to foster state religion follows naturally from his conviction that we lack the early church’s deep adherence to the faith’s central truths. He also points to the key role that natural law might play across religious and cultural lines. By rooting public appeals to cultural reform in the natural law, others can be persuaded to adopt laws and policies that correspond to Christian moral teaching even if they themselves are not believers. This is a view that has the advantage of starting from the real fact of diversity and treating fellow citizens as equals.

The book concludes with a thoughtful meditation on Christian hope. Here one of the strongest comparisons between the Roman world and our own becomes clear: Romans’ hopes rested entirely in the politics and history of the city, and our modern world likewise “ties all its hopes to redistributions of power and new political configurations. While these acts encourage justice here and now, the church knows they are not enough.” Moreover, the early church shows that the powerful witness of placing the love of God first leads naturally to a love of our fellow man. Christian belief also ought to chasten dramatically our expectations for political life in this fallen world. It also checks our desires to glory in secular accomplishment, as well as our dreams for political change. Nations will rise and fall in God’s goodly providence, and our faith will see us through.

As citizens in a republic—even a decadent one—we have power that the early Christians did not.

Nevertheless, Presley emphasizes that we should not despair of our world. We must not forget the differences between our world and the Roman one. As citizens in a republic—even a decadent one—we have power that the early Christians did not to promote public virtue and decency. Yet Presley offers a warning in this regard: “In our intellectual arguments, we must walk this line between rhetoric and virtue and make persuasive arguments, but never in ways that undermine our call to embody virtue.”

This is perhaps the greatest danger for politically active Christians at this moment. In the name of “fighting back” or “winning so that we have a church,” it is too easy for Christians to mistake their secular aims for sacred ones, and to embrace vicious means in the hopes of securing our political future. We would do well to heed the author.