At the World’s Parliament of Religions on September 11, 1893, a 30-year-old monk named Swami Vivekananda stood confidently on the platform. In part from inner spiritual conviction, but also out of deep historical awareness, he spoke to the rapt Chicago audience a bold, simple greeting: “Sisters and Brothers of America!” The crowd resounded with thunderous applause—an acclamation fit not for a stranger from a strange land but rather a brother returned home after a journey of many years.

What does a Hindu spiritual leader have to teach American Christians today? Perhaps the best of their own faith.

No one man introduced Hinduism to America. Iconic Americans such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Walt Whitman steeped themselves in the Upanishads as soon as they appeared in English. The ancient spiritual heritage of India was freely adapted in works of philosophy and art that shaped the early republic. India and America have likewise never been truly strangers. For the bulk of the 18th century, the 13 colonies along America’s Atlantic coast and growing slices of the Indian subcontinent were subject to the British crown. Their colonial administrations differed wildly, each capable of tyranny, but India’s was more uniformly brutal and capricious. India and America also shared a heritage of English common law, which was leveraged by the founders of both nations in freedom struggles separated more by time than by spirit.

What was rare in America were encounters between ordinary Western Christians and Hindu teachers. Hinduism directly reached only a sliver of the American elite until the close of the 19th century through the works of careful Indologists and reckless occultists. Encounters between American and Indian patriots, however, were entirely new. American national consciousness was mature by the 19th century, while the Indian national consciousness was just being born. Swami Vivekananda was an outstanding example of both: a Hindu monk and an Indian patriot who successfully captivated America and transformed India through the mutual enrichment of both.

Vivekananda would address the World’s Parliament of Religions six times over the course of six days. The longest of these addresses, a paper on Hinduism, was delivered in half an hour. His shortest, a plea for Christian missionaries to provide not merely preaching but material aid to impoverished Indians, under two minutes. His total speaking time on the platform that September was scarcely over an hour. It was all he needed. His message was one of holiness, purity, and charity that rejected sectarianism, bigotry, and fanaticism. Swami Nikhilananda, in his brilliant Vivekananda: A Biography, notes what set Vivekananda apart: “Whereas every one of the other delegates had spoken for his own ideal or sect, the Swami had spoken about God, who, as the ultimate goal of all faiths, is their innermost essence.”

Religious Indifferentism?

Vivekananda’s hope for religious unity was grounded not on belligerent triumphalism nor a patronizing dismissal of religious differences. From an address given in September 1893:

The seed is put in the ground, and earth and air and water are placed around it. Does the seed become the earth; or the air, or the water? No. It becomes a plant, it develops after the law of its own growth, assimilates the air, the earth, and the water, converts them into plant substance, and grows into a plant.

Similar is the case with religion. The Christian is not to become a Hindu or a Buddhist, nor a Hindu or a Buddhist to become a Christian. But each must assimilate the spirit of the others and yet preserve his individuality and grow according to his own law of growth.

The wild success of Vivekananda and his message at the World’s Parliament of Religions did not sit well with the parliament’s theologically liberal organizers nor with its religiously conservative critics. Some of the parliament’s most enthusiastic promoters were theologically liberal Protestants who saw it as an opportunity to demonstrate the superiority of a modernist and progressive Christianity over the superstitious and backward religions of the non-Western world. And a convincing case can be made that Pope Leo XIII was the most prominent, albeit belated, conservative critic of the parliament.

Thousands of Catholics, clergy and laity, attended the parliament in 1893. Archbishop Feehan of Chicago and Bishop Kean, rector of the Catholic University, attended. Cardinal Gibbons opened the first session of the parliament by praying the Our Father. Two years later, however, in an apostolic letter to the Apostolic Delegate to the United States, Pope Leo XIII addressed this participation. Fr. Francis J. Connell, C.Ss.R., in an article titled “Pope Leo XIII’s Message to America” published in the American Ecclesiastical Review in 1943, provides an excellent summary: “Though couched in the form of a suggestion and pervaded with benignity and kindness, the message of Leo XIII unquestionably manifested disapproval of the part which Catholics had taken in the Chicago Parliament of Religions and forbade future activities of a similar nature.”

Pope Leo XIII’s concern with Catholic participation in the parliament was that it could be construed as a religious indifferentism, a conviction that differences in religious belief are of no importance. Subsequent church teaching, such as Nostra Aetate (Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions), which was promulgated at the Second Vatican Council, and ecumenical interfaith gatherings such as the World Day of Prayer for Peace (1986) organized by Pope St. John Paul II in Assisi, Italy, would facilitate greater understanding of the relationship between Christian and non-Christian religions.

Vivekananda saw religious differences as both real and consequential. What he did not see was that those differences should necessitate hostility or preclude mutual understanding and enrichment.

A Curious and Adventurous Boy

Religions differ on matters of both historical fact and metaphysical truth. Islamic tradition claims that Christ’s crucifixion was not real but only apparent, while St. Paul proclaims that “we preach Christ crucified, unto the Jews a stumbling block, and unto the Greeks foolishness” (1 Cor. 1:23). St. Paul also preaches that God has become incarnate once: “When the fulness of the time was come, God sent forth his Son, made of a woman, made under the law, to redeem them that were under the law, that we might receive the adoption of sons” (Gal. 4:4–5). Krisha tells Arjuna that God incarnates periodically: “For the protection of the good, for the destruction of the wicked, and for the establishment of dharma (religion), I am born in every age” (Bhagavad Gita 4.8).

What then is the ground on which Vivekananda builds a case for the harmony of religions? The answer is found in the story of his life. A boyhood of devotion, an adolescent crisis of faith, and an answer to that crisis in the form of a beloved guru.

Narendranath Datta, not yet having taken the name Swami Vivekananda, was born January 12, 1863. His father was an attorney at the High Court of Calcutta. He was a cosmopolitan agnostic, loved both English and Persian literature, and possessed an indiscriminate appreciation of the high culture of Christian, Islamic, and Hindu civilizations. His broadmindedness went hand in hand with generosity toward family and friends. Narendra’s mother by contrast was a paragon of traditional Hindu womanhood. Deeply pious, she would sing the young Naren devotional songs, tell him tales from India’s great epics the Ramayana and Mahabharata, and comfort him with the repetition of the divine name of Shiva.

This curious couple raised a most curious and adventurous boy who was fond of animals, often lead other children in games, and would, unbeknownst to his parents, give away household items to wandering monks. He had a conventional Hindu piety but also experienced vivid visions in meditation. Even in boyhood, he rejected religious bigotry and crass sectarianism. In his office, as was the orthodox Hindu custom at the time, Narendra’s father kept separate tobacco pipes for clients of different castes and religions. The young Narendra smoked from them all, observing, “I cannot see what difference it makes.”

Upon his entrance to the Presidency College of Calcutta in 1879, the young Narendra began a rigorous Western education and experienced a crisis of faith. The study of Western philosophy, history, and science consumed and fascinated him. This was a period of immense learning and growth, but also a crisis of identity. The social problems of India became more visible through Western-educated eyes. Narendra questioned Hindu ritualism, the place of women in society, child marriage, casteism, and a whole raft of superstition he would later come to call “Don’t-touchism.” He later came to understand that this Don’t-touchism “is not Hinduism: it is in none of our books; it is an unorthodox superstition which has interfered with national efficiency all along the line.” The damage to his conscience had, however, already been done. Narendra would oscillate between skepticism and liberal Hindu reform movements like the Brahmo Samaj until he found his guru.

Narendra the young skeptic knew that nothing less than the experience of God could resolve his crisis of faith. To prospective religious teachers, he would put the pointed question: “Sir, have you seen God?” Stunned interlocutors could give only hedging or equivocating answers. Such answers were of no use to Narendra, and everywhere he turned for a prospective teacher, that was all he found.

Then Naren remembered an offhand remark concerning the modern paucity of ecstatic trances. During a lecture on William Wordsworth’s “The Excursion,” his professor, the theologian William Hastie, shared, “I have known only one person who has realized that blessed state, and he is Ramakrishna at Dakshineswar.” A relative also recommended, “If you really want to cultivate spirituality, then visit Ramakrishna at Dakshineswar.” And so he did. Narendra asked once more his bold question, “Sir, have you seen God?” Ramakrishna answered without hedge or equivocation:

Yes, I have seen God. I see Him as I see you here, only more clearly. God can be seen. One can talk to Him. But who cares for God? People shed torrents of tears for their wives, children, wealth, and property, but who weeps for the vision of God? If one cries sincerely for God, one can surely see him.

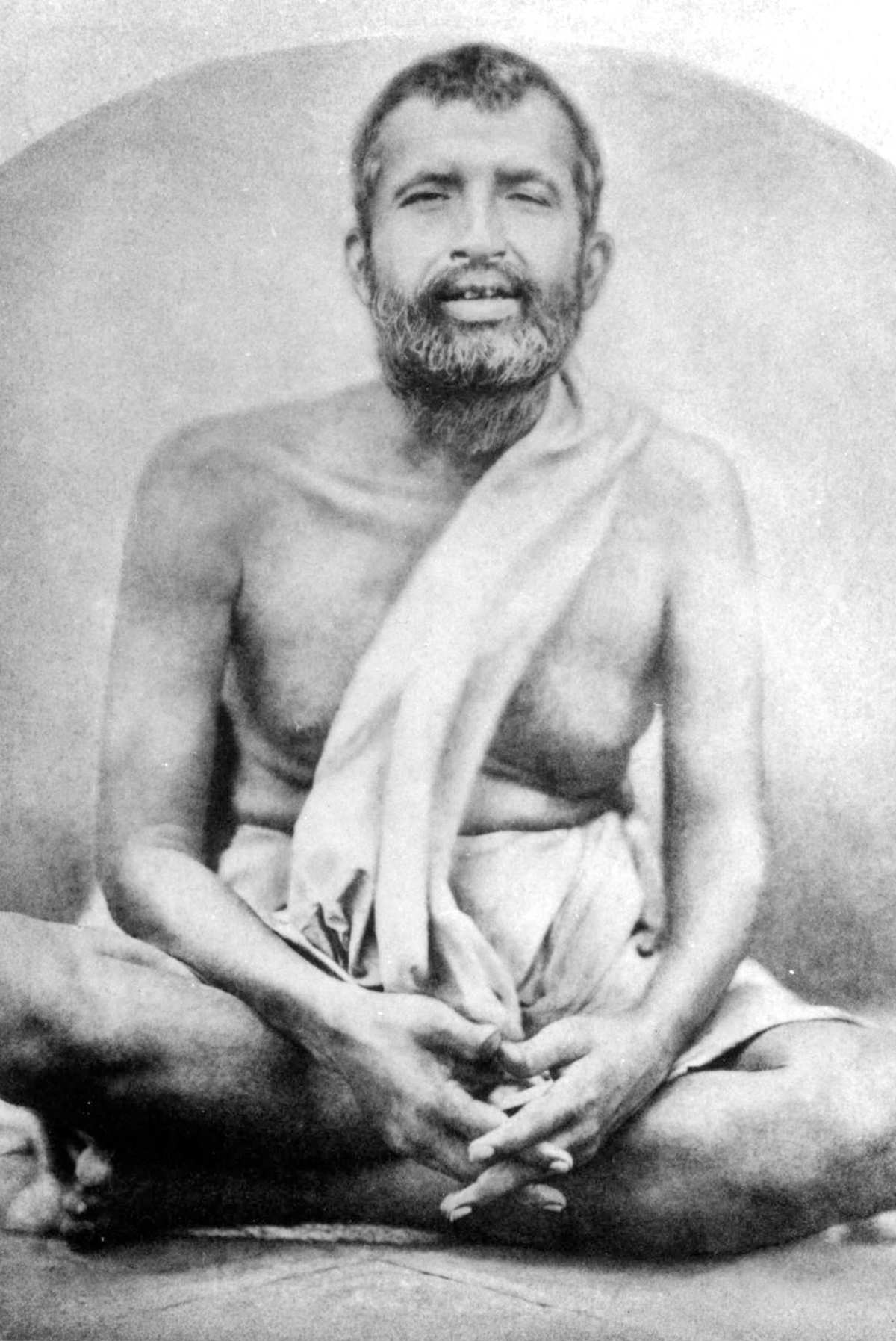

Ramakrishna was a Hindu priest and mystic who was born in 1836. In 1855 he became a priest at the Dakshineswar Kali Temple in a small village outside of what was then Calcutta. There he cultivated a succession of spiritual practices drawing from diverse sects across Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity, claiming that each led him to experiences of God-realization. He often entered states of Samadhi, total contemplation and absorption in the divine. During his life a group of devotees, including the young Narendra, would regularly meet to hear his teaching and form a spiritual community that would endure through Ramakrishna’s passing away from throat cancer in 1886.

These teachings are most exhaustively documented in the Bengali language classic Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita (The Nectar of Sri Ramakrishna’s Words). Based on the journals of the householder devotee Mahendranath Gupta, this work was published in five installments from 1902 to 1932. Its most beloved English translation, titled The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, was made by Swami Nikhilananda and published in 1942.

What is the ground on which a harmony of religions can be based that does not devalue and dismiss religious difference? From where can a harmony emerge from a cacophony of conflicting claims of historical fact and metaphysical truth? One answer is found in the unique perspective of Ramakrishna’s eclectic spiritual practice. In his book Infinite Paths to Infinite Reality, Ayon Maharaj (now Swami Medhananda) argues that

Sri Ramakrishna champions the religious pluralist doctrine that there are infinite paths to the Infinite Reality. … Every religion is an effective means of attaining the common salvific goal of God-realization, the direct spiritual experience of God in any of His innumerable aspects or forms.

Vivekananda’s definition of religion, as it appears in the preface to his commentary of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali Raja Yoga, is the definitive articulation of his guru’s solution to the question of the harmony of religions:

Each soul is potentially divine. The goal is to manifest this Divinity within by controlling nature, external and internal. Do this either by work, or worship, or psychic control, or philosophy—by one, or more, or all of these—and be free. This is the whole of religion. Doctrines, or dogmas, or rituals, or books, or temples, or forms are but secondary details.

The world’s major religions all stress a goal of unity with the divine and the potential of men and women to realize that unity. What Vivekananda means by the control of nature, external and internal, is control of the senses and mind. He categorizes spiritual disciplines into the four broad categories of work, worship, psychic control (meditation), and philosophy. He lectured on each of these categories of spiritual disciplines, which were eventually published in volumes titled Karma Yoga (work), Bhaki Yoga (worship), Raja Yoga (meditation), and Jnana Yoga (philosophy). While Vivekananda viewed doctrines, rituals, scriptures, and worship as “secondary details,” they were nevertheless not unreal or inconsequential ones.

Vivekananda believed the Christian religious tradition to be disposed to the spiritual discipline of work (karma).

This way of thinking about the harmony of religions is a unique contribution by Ramakrishna and Vivekananda to the question, but ready resonances can be heard in the teaching about the nature of religion from other religious traditions. Paragraph 28 in the Catechism of the Catholic Church is one such example:

In many ways, throughout history down to the present day, men have given expression to their quest for God in their religious beliefs and behaviour: in their prayers, sacrifices, rituals, meditations, and so forth. These forms of religious expression, despite the ambiguities they often bring with them, are so universal that one may well call man a religious being:

“From one ancestor (God) made all nations to inhabit the whole earth, and he allotted the times of their existence and the boundaries of the places where they would live, so that they would search for God and perhaps grope for him and find him—though indeed he is not far from each one of us. For ‘in him we live and move and have our being.’” (Acts 17:26–28; NRSV)

The categories of work, worship, meditation, and philosophy are meant to provide conceptual tools for spiritual practitioners rather than rigid boundaries. One or more (or all) of these can resonate depending on an individual’s disposition and temperament. What is true of individuals is also true of societies and religious traditions.

A Christian Spirit of Service

Some months after Ramakrishna’s passing in 1886, Narendra together with other disciples of Ramakrishna destined for monastic life gathered around a fire for meditation. Swami Nikhilananda recounts:

Suddenly Naren opened his eyes and began, with apostolic fervour, to narrate to the brother disciples the life of Christ. He exhorted them to live like Christ, who had no place “to lay his head.” Inflamed by a new passion, the youths, making God and the sacred fire their witness, vowed to become monks.

It was only after some of the new monks returned to their rooms that they realized it was Christmas Eve, “and all felt doubly blessed.”

‘Better be ready to live in rags with Christ than to live in palaces without him.’

Thus, the harmony of religions was observed, in a natural and spontaneous way, from the very beginning of the Ramakrishna Order. It was an auspicious beginning to an order that would come to embrace a spirit of selfless service. Vivekananda believed the Christian religious tradition to be disposed especially by its own nature to the spiritual discipline of work (karma).

There is a lively debate today over whether the United States is or ever was a “Christian nation” and, if so, just what that means. Vivekananda’s position on this question is unambiguous as revealed in a letter to a friend penned a little over a month after his arrival in the States in 1893. “I am here amongst the children of the Son of Mary, and the Lord Jesus will help me.” Vivekananda experienced friendship and generosity as well as enmity and meanness from Christians in America. He encountered Americans of other faiths and no faith at all. But in America Vivekananda saw how a Christian spirit of service animated the commercial, civic, and social life of the nation.

Among Vivekananda’s most powerful initial impressions of America was of its great prosperity. The hospitality extended by his American friends toward him was so lavish, it scandalized him. The contrast to the poverty in India so moved him that he implored God to show him how to help. Swami Nikhilananda recounts that this inspired him to “study American life in its various aspects, especially the secret of the country’s high standard of living, and he communicated to his disciples in India his views on the promotion of her material welfare.”

Vivekananda also saw the spiritual dangers of materialism, which he extoled his Christian audiences to always guard against: “If you can join these two, this wonderful prosperity with the ideal of Christ, it is well; but if you cannot, better go back to him and give up these vain pursuits. Better be ready to live in rags with Christ than to live in palaces without him.”

The underlying principles of American civic life—freedom, equality, justice—impressed Vivekananda, and so did such institutional frameworks as the rule of law and republican government. In these he saw a spiritual foundation the contours of which are ably described by Swami Nikhilananda:

Both the Holy Bible and the philosophy of Locke influenced the Bill of Rights and the American Constitution. Leaders imbued with the Christian ideal of the Fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of men penned the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence, which clearly set forth its political philosophy, namely, the equality of men before God, the state, and society.

Vivekananda lamented the failure of India to ground a similar set of principles in Hinduism. “No religion on earth preaches the dignity of humanity in such a lofty strain as Hinduism, and no religion on earth treads upon the necks of the poor and the low in such a fashion as Hinduism. Religion is not at fault, but it is the Pharisees and Sadducees.”

No facet of American social life so impressed Vivekananda as the role of American women. As just one example, Mary Hale of Chicago had been among his earliest friends and benefactors. He noted early and with wonder the prominent role American women played in the country’s philanthropic, educational, and cultural life: “Nowhere in the world are women like those of this country. How pure, independent, self-relying, and kind-hearted! It is the women who are the life and soul of this country. All learning and culture are centred in them.”

The contrasting degradation of women in India had contributed to Vivekananda’s own earlier crisis of faith. Swami Nikhilananda relates that “he often thought that the misery of India was largely due to the ill-treatment the Hindus meted out to their womenfolk. Part of the money earned by his lectures was sent to a foundation for Hindu widows at Baranagore.”

No facet of American social life so impressed Vivekananda as the role of American women.

The social problems of India were not, in Swami Vivekananda’s estimation, the consequence of Hinduism, but rather the result of its abuse. In a letter to Raja Ajit Singh Bahadur of Khetri, who had encouraged Vivekananda to attend the Parliament of the World’s Religions and provided financial support, he wrote:

The more, therefore, the Hindus study the past, the more glorious will be their future, and whoever tries to bring the past to the door of everyone is a great benefactor to his nation. The degeneration of India came not because the laws and customs of the ancients were bad, but because they were not allowed to be carried to their legitimate conclusions.

In this present vale of tears, even religion itself can tragically degenerate. Reform and renewal are the constant task of those who seek God and to do his work in the world. Vivekananda would return to India to restore its glorious Hindu past armed not only with knowledge of that past but with inspiration from late-19th-century America’s Christian present.

The Vitality of Religion Necessary for Reform

When Vivekananda left India for America, he was an obscure wandering monk. On his return in 1897, he was the world’s most famous and celebrated Hindu teacher. But what sort of teacher would he be, and how would his vision for national and social renewal be accomplished?

‘God and truth are the only politics in the world; everything else is trash.’

Shortly after his return, a Hindu pandit (wise man) attempted to draw him into sectarian religious controversies, and Vivekananda answered, “This incarnation of mine is to help put an end to useless and mischievous quarrels, which only distract the mind and make men weary of life, and even turn them into sceptics and atheists.” His program for national renewal would reject sectarianism, bigotry, and fanaticism while recognizing that the only path to a flourishing commercial, civic, and social life was through religious renewal. “If you succeed in the attempt to throw off your religion and take up either politics or society,” said Vivekananda in a lecture entitled “My Plan of Campaign,” “the result will be that you will become extinct. Social reform and politics have to be preached through the vitality of your religion.”

To this end, Swami Vivekananda would found the Ramakrishna Mission less than six months after his return to India. Swami Nikhilananda describes the broad contours of the organization this way:

Its methods of action were to be: (a) to train men so as to make them competent to teach such knowledge and sciences as are conducive to the material and spiritual welfare of the masses; (b) to promote and encourage arts and industries; (c) to introduce and spread among the people in general Vedantic and other ideas as elucidated in the life of Sri Ramakrishna.

The organization would stay aloof from party politics. As Swami Vivekananda had once written to a friend, “I do not believe in any politics. God and truth are the only politics in the world; everything else is trash.”

Such a program is unremarkable to the ears of American Christians. By the late 19th century, ecumenical and parachurch organizations that worked toward the material and spiritual uplift of the masses, a vibrant cultural and economic life, and the spreading of religious teachings to the general public permeated national life. But for Indian Hindus, such organizations were unheard of. Even intimate associates of Vivekananda, some of them fellow devotees of Ramakrishna, believed such a program to be the product of his Western education and travels to America and Europe. To them such bodies were foreign novelties that could only serve to distract from the spiritual life.

To such aspersions, Vivekananda reacted with fury:

What do you understand of religion? You are babies. You are only good at praying with folded hands: “O Lord! how beautiful is Your nose, how sweet are Your eyes,” and all such nonsense; and you think your salvation is secured. … Study, public preaching, and doing humanitarian works are, according to you, Maya because Shri Ramakrishna did not do them himself!

Vivekananda would eventually win his brother disciples over to his way of seeing things, and not through outbursts of emotion and rough humor but patient and careful explanation of karma yoga, that selfless service rendered to others. Ramakrishna himself had taught infinite paths to Infinite Reality. Vivekananda believed that, in the modern world, action was required for not just material but also spiritual progress. The need was particularly great in India, where centuries of colonialism and religious decadence had rendered the masses, in his own estimation, degraded and inert.

His misguided brother monks who were skeptical of a revitalization of the commercial, civic, and social life of India through religious renewal were right about one thing: Vivekananda had seen such things work in a Christian America. Praise God that he did! There is a special Christian genius for organization, the spirit of which Vivekananda sought to assimilate into Hinduism to reinvigorate India when he saw that “the Christians are, even in the darkest days, even in the most superstitious Christian countries, always trying to prepare themselves for the coming of the Lord, by trying to help others, building hospitals, and so on. So long as the Christians keep to that ideal, their religion lives.”