In a popular 17th century work called Of the Principles and Duties of Natural Religion, the Anglican John Wilkins defended the proposition that “Religion is the Cause of Riches.” The true Christian faith, he argued, prepares one for success because its ethical principles convey “all the lawful Arts of Gain and good Husbandry.” These include a “heedfulness to improve all fitting Opportunities of providing for our selves and Families, being provident in our Expences, keeping within the Bounds of our Income, [and] not running out into needless Debts.” Wilkins’ discourse captures what was at the time a common English belief: Virtue, profitable commercial enterprise, religion, and the social good are of a piece.

The Puritans may not have invented capitalism but they certainly imbued it with moral worth.

Today many associate this belief with the English Protestant subgroup known as the Puritans, a movement that can roughly be identified, as historian Margo Todd has described it, by shared commitments “to purging the Church of England” of “Romish ‘superstition,’ ceremonies, vestments and liturgy, and to establishing a biblical discipline on the larger society, primarily through the preached word.” The Puritans were not unique harbingers of English commercial spirit. But in their teaching and practice, they undeniably contributed to the spirit of the age. That spirit valorized commerce and elevated perceptions of merchants. By the 18th century, the figure of the merchant was no longer reviled but heralded, according to the writer and playwright Richard Steele, as “the greatest Benefactor of the English nation.”

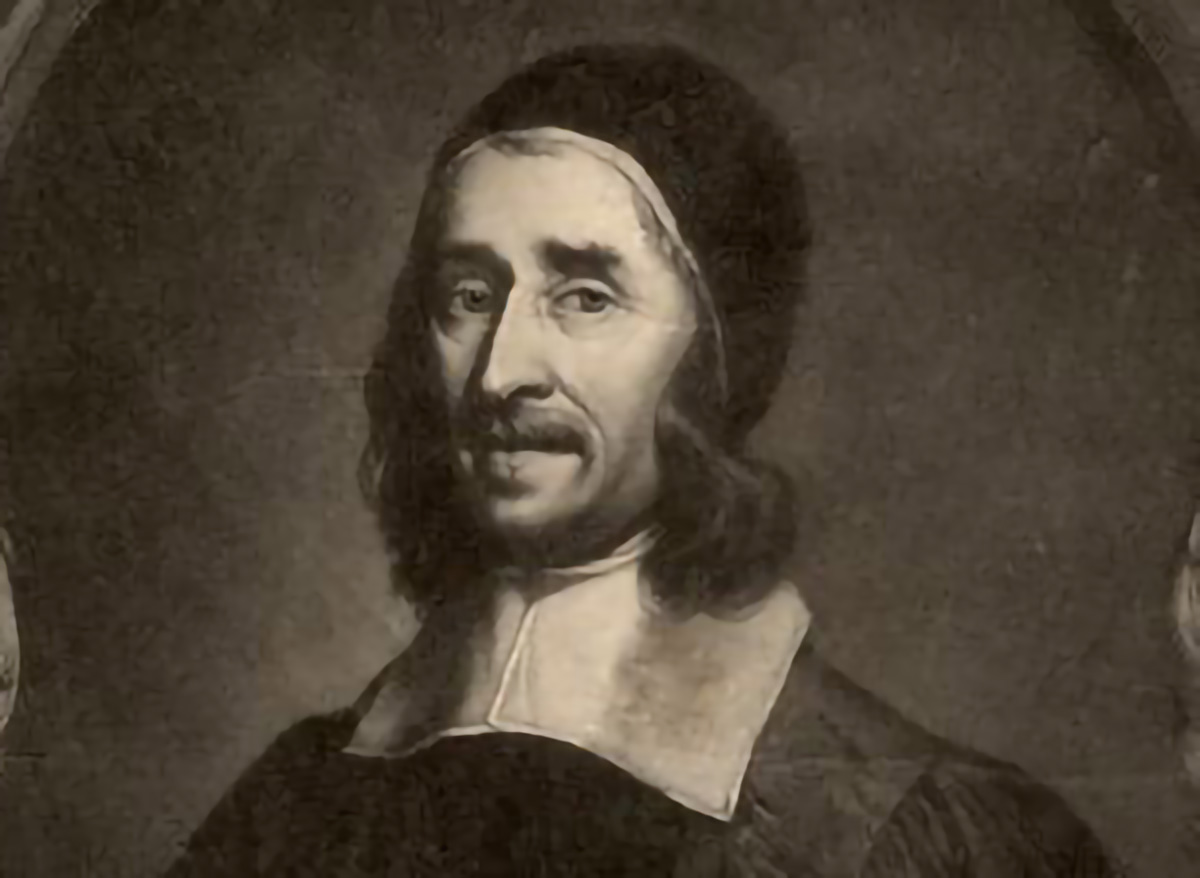

The Puritans inherited long-standing Christian suspicions about commercial life. William Perkins, a founding figure in the Puritan intellectual tradition, advanced traditional arguments against the practice of usury. He condemned common loan practices of the early 17th century as unethical. So, too, did he condemn price speculation. He argued that speculators should be kept from partaking in the Lord’s Supper until they expressed penitence to the church community. Puritan perspectives changed, however.

Richard Baxter, the most influential Puritan teacher of the 17th century, wrote in his hugely influential Christian Directory that each has a duty to “labour in a manner as tendeth most to [his] success and lawful gain” and a responsibility to “lawfully get more” when the opportunity presents itself. That passage was later canonized by Max Weber as exemplifying the “Protestant ethic” out of which, he believed, the spirit of capitalism emerged. In 1684, the minister Richard Steele, in his popular work The Tradesman’s Calling, argued that the “Market-Price” is “the surest Rule” for justice in exchange, and the attempt to determine a moral rate of profit is a fool’s errand. Across the Atlantic, Samuel Willard in Boston dismissed traditional Christian arguments against the charging of interest as “Noise and Railery, without solid Reason or Cogency or arguing.” In contrast to the Aristotelian notion of money as sterile, Willard argued that money was “the most Fertile thing in the World.” Commerce, in his opinion, should be liberated from the restrictive moral rules of church governance and left to the consciences and voluntary agreements of its practitioners.

Puritans exhibited increasing commercial spirit not only in theory but in practice. This can be clearly seen in the mercantile communities of New England, as Mark Valeri has cataloged in his book Heavenly Merchandize: How Religion Shaped Commerce in Puritan America (2010). Commercial heavyweights like the Bostonian John Hull pursued profits, in the 1660s and 1670s, through transatlantic credit and exchange on the understanding that these activities were not just consistent with their faith but also acts of public service to be pursued with diligence for the good of God’s kingdom.

In England, the entrepreneurial spirit manifested similarly in commercial ventures, but also in Puritan zeal for technological and scientific innovation. The new experimental science, in the mode of Bacon and Newton, aimed at illuminating the order of God’s creation and drawing fruit from creation. The fruit often took the form of commercially profitable commercial applications.

Notable Puritans of the day included polymath John Wilkins, chemist Robert Boyle, botanist John Ray, and the political economist William Petty. In their enthusiastic pursuit of practical knowledge and improvement, these men and their colleagues contributed to the proto-industrial developments of the century. The Puritans were not uniquely responsible for the rise of capitalism, but they certainly fostered what Joel Mokyr has called a “culture of growth.” This culture was arguably a necessary precondition for the great enrichment of northwestern Europe and America that took off in the late 18th century.

What drove the development of Puritan economic ethics? Weber famously emphasized the doctrine of predestination. In the face of deep psychological uncertainty about the state of his salvation, the Puritan fell back on the industrious pursuit of material prosperity. The achievement of material prosperity, Weber theorized, served as a signal: Material success could be taken as an indication of God’s favor; that indication signaled to the Puritan’s community and to the Puritan himself that he was likely among God’s elect. This part of Weber’s theory falls flat for several reasons. The main reason pertains to historical theology. One is hard pressed to find evidence for such beliefs in the writings of the Puritans. They certainly are not present in the teachings of Calvin, for whom material prosperity was no sure indication of God’s election.

A more nuanced suggestion comes from R.H. Tawney in his 1926 book, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism. Tawney claims that by the end of the 17th century, the Puritan consensus was to respect commerce as a separate sphere of life with its own logic. Tawney sometimes comes across as suggesting that Puritan divines simply lost interest in governing the conduct of actors in the marketplace or that economic interests usurped theological conviction. Attention to sermons and pamphlets of the period indicate that this was not the case. Tawney’s broader point, however, is that the development of Puritan economic ethics must be understood in conversation with analytical developments in English political economy. “The progress of economic thought,” he argues, “fortified the economic virtues” in the Puritan mind. The teachings of the early political economists informed the substance of Puritan moral theology, inclining them to reassess traditional perspectives more skeptical of commercial life.

A merchant’s gain was portrayed as serving not only his own benefit but also that of the community and even the nation.

The early political economists, such as William Petty (a Puritan), Josiah Child, Edward Misselden, Nicholas Barbon, Charles Davenant, and John Locke (the son of a Puritan), promoted the national benefits of mercantile activity. Their analyses called into question the traditional views of the superior dignity and usefulness of the landed aristocracy as compared to merchants. A merchant’s gain was portrayed as serving not only his own benefit but that also of the community and even the nation. Building on decades of such arguments, Nicholas Barbon, in his Discourse of Trade, argued in 1690 that Europe had grown more populous, better fed, and healthier by virtue of trade and its enabling levers of credit. Through participation in commercial life, laborers, moreover, benefited themselves and their fellow citizens by refining the “Natural Stock” of their country’s resources into “a Thousand useful Things.”

Economic arguments intertwined with political discourses associating increased economic freedom with the interests of religious toleration and hence Protestant dissent. Since the reign of Elizabeth, Puritans had opposed such economic regulations as crown-chartered monopolies, trade restrictions, occupational licensing requirements, and certain taxes. Their opposition formed part of a broader program of resistance to extensive crown prerogatives and was motivated by concern for religious toleration. David Hume wrote in his History of England that under Charles I, when this opposition peaked in the middle of the 17th century, parliamentary “debates concerning tonnage and poundage went hand in hand with … theological or metaphysical controversies,” and the “merchants who should voluntarily pay these duties, were denominated betrayers of English liberty, and public enemies.”

The analytical arguments about the social benefits of commerce advanced the association of economic freedom and religious toleration. The emergent commercial ideology proved deeply congenial to some long-standing elements in Puritan moral theology: teachings on work, callings, and the common weal.

The Genesis creation narrative portrays work as a creative feature of God’s design for humankind—it is only after the introduction of sin into the world that work turns to toil. Jesus’ parables convey an obligation to stewardship, diligence, and even, as in the Parable of the Talents (Matt. 25:14–30), the pursuit of honest gain. Positive visions of work can be found in the Christian tradition reaching back to the early church fathers, affirmed and expanded by the teachings of early monastic figures such as Benedict of Nursia.

Teachings on the redemptive aspects of work came to the foreground during the Protestant Reformation, however. Part of the foregrounding came in polemical writings against monastic life and corruptions of the institutional church. Professional clerics, Protestants argued, have no monopoly on the claim to sanctified work. The people of God are together members of the priesthood of all believers. The priesthood spans a great variety of worldly occupations, including seemingly mundane activities, and it is often through faithfulness in such mundane activities that the kingdom of God moves forth.

These perspectives complemented Protestant theologies of works. Luther emphasized the importance of good works, not for salvation but for the good of one’s community. God does not require our good works, but our neighbors do. For our neighbor’s sake, once we have been reconciled to God in love through Christ, we are to move outward in love to socially profitable acts. In a Christmas sermon, Luther said: “In this conduct of the shepherds we find a valuable and beautiful lesson. After they have obtained the revelation from heaven, and the true knowledge of Christ, they do not run out into the dessert, as the foolish monks and nuns run into cloisters, but remain in their calling, and are useful to their fellow men.” In a similar mode, Calvin taught of God’s provision for humankind—a species of common grace—through a diversity of human activities. He emphasized the vital importance of our participation in God’s providence through the stewarding of our gifts and talents for the good of our neighbors. We should, he wrote, “join zeal for another’s benefit with care for our own advantage,” ultimately subordinating “the latter to the former.”

The emphasis on the potential sanctity of ordinary work and its contribution to the common weal found a strong foothold in the Puritan intellectual tradition. English Puritans focused on the distinction between the shared general calling of Christians to faith in Christ and the particular earthly calling of each Christian to a course of life beneficial to his community. The emphasis on considering the social benefits of a calling in forming one’s life plans was pronounced. At the turn of the 17th century, William Perkins wrote that the Christian is “the freest man of all men in the world. … And yet, for all this, he must be a servant of every man. But how? By all the duties of love as occasion is offered, and that is for the common good of all men.” Each must devote himself to a calling, Perkins continued, “so that he may be a good and profitable member of some society and body.”

It was not to confirm their election that the Puritans strived but to glorify God in making a becoming use of their resources.

The stress on social benefits in Puritan moral theology can also be traced to the influence of Christian humanism. Associated with the Dutch theologian Desiderius Erasmus, humanist philosophy took hold in 16th and 17th century England, eventually leading to extensive reforms and changes in curricula at universities including Oxford and Cambridge. Like their continental counterparts, English humanists such as Thomas Starkey prioritized encounters with classical texts in the original languages and elevated the active over the contemplative life. The active life was to be pursued as a means of serving the common good; idle contemplation was to be avoided. As Starkey wrote in 1533: “To this all men are born and of nature brought forth: to commune such gifts as be to them given, each one to the profit of others.” The humanist influence, interacting with Protestantism generally, contributed to the pronounced emphasis on social usefulness in English culture. That emphasis is well captured in the moral philosophy of David Hume in the 18th century. In a eulogy to merchants, he drew attention to their social usefulness, taking that usefulness as sufficient evidence of their moral worth: “In general, what praise is implied in the simple epithet useful! What reproach in the contrary!”

Puritan economic ethics grew from a matrix of Protestant teachings on the affirmation of the mundane and humanist emphases on the importance of an active life and the cultivation of civic virtue for the sake of the common weal. The combined influence of these strands of teaching help us begin to appreciate the Puritan valorization of ordinary striving, including the trades; exhortation for the faithful to select socially beneficial earthly callings; and stress on the importance of hard work and diligent application. It is in that basic theological context that Richard Baxter’s statement about our obligation to pursue gain must be taken. Theologically speaking, it was not to confirm their election that the Puritans strived but to glorify God in making a becoming use of their resources, a beatitude corresponding to advancing the good of society.

In the context of discussing the Puritan Richard Steele, Tawney remarks in his book that “trade itself is a kind of religion.” The point is overstated, but it highlights the influence of political economy on Puritan thought. Given the emphasis on the importance of social benefits and practicality, it should not come as a surprise that Puritan moral theology absorbed findings of new perspectives into the social consequences of commercial activity—findings of political economy. In Boston in 1701, Cotton Mather indicated the influence of these findings, emphasizing God’s desire for humans to exist in mutually beneficial relations: “God hath made man a Sociable Creature. We expect Benefits from Humane Society. It is but equal, that Humane Society should Receive Benefits from Us. We are Beneficial to Humane Society by the Works of that Special Occupation, in which we are to be employ’d, according to the Order of God.” Attention to the development of Puritan economic ethics reminds us that the disciplines of moral theology and social science do not exist in isolation, and they remain isolated from one another at their peril.

The Puritans were, as has been mentioned, not uniquely responsible for the rise of English commercial spirit, let alone the genesis of what some now call capitalism. But they certainly contributed to the moral affirmation of commercial life. They participated in the formation of the spirit of the age, a spirit that formed the English into, as William Blackstone describes them, “a polite and commercial people.” In America, Alexis de Tocqueville later observed, “professions are more or less laborious, more or less profitable; but they are never either high or low: every honest calling is honorable.” Here, too, can we discern part of the moral legacy of the Puritans.