There are good reasons to avoid the subject of missionary Puritanism—it is too fraught. Nowadays, Christian missions reek of white-savior cultural imperialism (at best). Puritans have a bad enough reputation already without this one being added to their charge sheet. And anyway, we tend to think they were not guilty. Their reputation in their own time, and since, was of being moralistic busybodies, too inward-facing and self-satisfied to bother with the godless heathen.

Puritans are not generally known for their missionary work, perhaps due to their stern predestinarian theology. But there are hidden stories of great works of evangelism among Native Americans that need telling—and retelling.

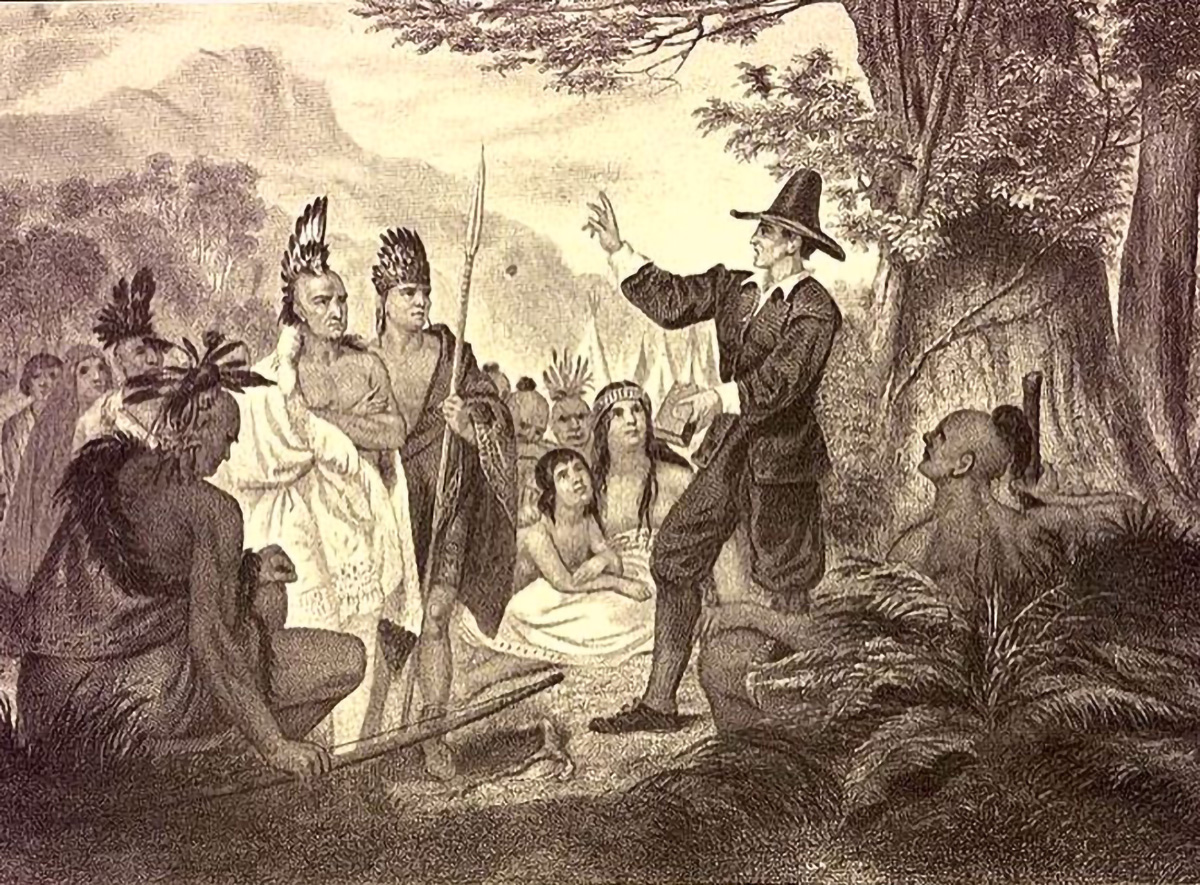

There is one famous exception: John Eliot, preacher at Roxbury, Massachusetts, known in his own lifetime as “the Apostle to the Indians.” But the “praying towns,” the self-governing Native American Christian republics he founded, were shattered by the bloody settler-Native conflict known as King Philip’s War (1675–1678). Eliot looks less like an exemplar than a voice crying in the wilderness to a Puritan culture that did not want to hear.

But there is a little more to be said about Puritan efforts to convert non-Christians in the colonial era. Eliot’s contemporaries may not look like active missionaries, but they had their reasons for acting as they did, reasons that might seem disconcertingly modern. Nor did Puritan missions die with Eliot; there are stories from the 1700s that show how Puritan missions were caught up in—and sometimes transcended—the cruelties and tragedies of an era of colonial rapacity.

It is sometimes said that Calvinist doctrines of predestination made Puritans indifferent to missionary efforts, but this is simply untrue. It was often the most convinced predestinarians—like Eliot—who were the most determined to claim the honor of finding God’s elect saints hidden in the heathen darkness. The early New England colonists, staunch defenders of predestinarian orthodoxy, claimed that “the propagating of the Gospel is the thing we do profess above all to be our aim in settling this Plantation.” But their theology did shape their distinctive view of how it should be done.

Their hope, as the first formal instructions issued to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629 put it, was to “draw the Heathen by our good example to the embracing of Christ and his Gospel.” Their predecessors at Plymouth shared the same ethos: to live such exemplary lives, as a preacher there in 1621 had told them, that Native Americans “should see and take knowledge of our labours, orders, and diligence, both for this life and a better,” and would thereby be persuaded of the merits of their religion. The Puritans’ “city on a hill” would be visible not only to Christendom but also to the pagan lands to the west.

This sort of talk may look desperately naive, or indeed a lazy excuse for inaction, but it was meant in earnest. For if there was one thing Puritan settlers passionately wanted to believe about themselves, it was that they were completely unlike the wicked Spaniards, who had enforced their false religion onto hapless Native Americans with cruel tortures. It became a matter of pride and of conscience: Puritans would not allow even a hint of religious coercion.

Instead, through their scrupulous fair dealing they would demonstrate that their faith was utterly unlike the Spaniards’ corrupt idolatry. They would not pressure “the heathen” in any way to convert. Nor would they have to, since Native Americans would be allured by the self-evident simplicity of the Puritans’ worship, the superiority of their doctrines, and the holiness of their lives. This was how the elect would be revealed. The Puritans’ only responsibility, and their only right, was to be witnesses and exemplars. There are moments when this scrupulous respect for the independent spiritual agency of Native Americans feels startlingly in tune with 21st-century pluralism.

When David Jones met a Native American who asked him when Easter would fall that year, he replied that 'my soul was filled with horror.'

This blithe faith that mere benevolent example would be all that was needed to win converts could almost be charming if it did not have a dark streak running through it. We can see its sincerity in the way that repeated failure produced genuine bafflement. In 1723, after a century of “allurement” had not borne very much fruit, Solomon Stoddard admitted he was flummoxed by how, when such a pious people settled among the Native Americans, “they did not enquire into it whether the Doctrine that they professed was [true], or not.” What was wrong with these people?

Perhaps it was the settlers’ fault, since the embarrassing truth was that they did not, in fact, set a terribly good moral example. For all their high hopes, the real example the English set for Native Americans was of greed, drunkenness, prejudice, sharp dealing, and land-hungry rapacity. It was also clear that sermons were not going to solve that problem. So another explanation beckoned: It was the Native Americans’ own fault. Stoddard concluded that they resisted Puritan allurement because they were “brutish,” mere animals. “We gave the Heathen an Example, and if they had not been miserably besotted, they would have taken more notice of it.” Indeed, settlers told themselves, Native Americans had not merely ignored the kindness and forbearance of their new neighbours; they had repayed it with violence. “Great care and pains hath been taken by us” with Native Americans, wrote one Massachusetts minister during King Philip’s War; and now, he observed with malicious relish, look how they thank us! Plainly they had proved themselves “unworthy of the grace of the Gospel.” All that the naivety of allurement achieved, in the end, was to allow the Puritans to cast themselves as the unlikely victims of the settler-Native encounter.

And so missionary Puritanism withered. We are left with figures like David Jones, a New Jersey Presbyterian who in 1772 took himself on a mission to the uncharted lands west of the Ohio river, intending to proclaim “the day of GOD’s mercy and visitation of these neglected savage nations.” His mission was an utter failure. Not only was he ignorant of Native American languages; he was also contemptuous of his interpreter, and bitterly resented how much he had to pay him. “Indians, from the greatest to the least, seem mercenary and excessively greedy of gain.” Nor was it much better when he did succeed in communicating. When Jones met a Native American who asked him when Easter would fall that year, he replied that “my soul was filled with horror,” expostulating against the “superstitious relics of the scarlet whore,” meaning not just Easter but the December festival he called “Popemas.” You can take the Presbyterian out of Princeton, but you can’t take Princeton out of the Presbyterian.

But there is more to missionary Puritanism than this. Two remarkable 18th-century cases show how hard it was for missionary Puritans to work against the background of rapacious settler expansion, but also show that, even in that context, something could be done.

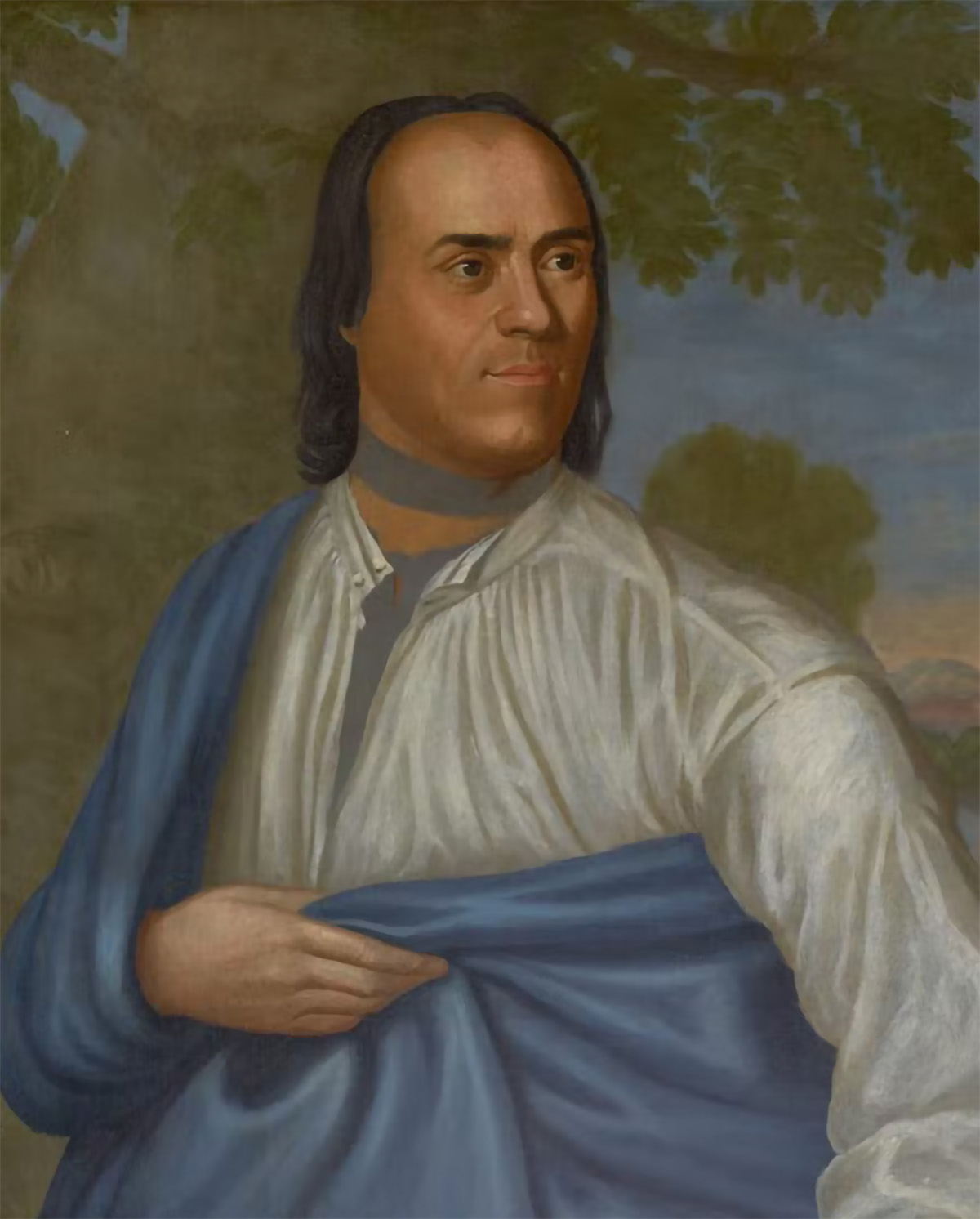

Samson Occom was a Mohegan Indian from Connecticut, born in 1723, converted by a revivalist preacher in his teens, and educated by the Congregationalist pioneer of Native American education, Eleazar Wheelock. Occom became a schoolmaster among the Mohegans of Long Island and in 1759 received Presbyterian ordination. He lived simply among his flock, supported himself and his family with the work of his hands, led an evangelical awakening on the island, and took what he called “a mild way” that avoided the divisions so often sparked by the revivals of this era. You could be forgiven for imagining him a man of saintly patience.

But that was not Occom, who knew exactly what it meant to be a Native American missionary in a white church. For one thing, he knew how little he was paid: £15 a year even after a decade’s service, less than a third of what the New England Company’s commissioners would have given to a callow white minister. “I Can’t Conceive how these gentlemen would have me Live,” he wrote. “What can be the Reason that they used me after this manner? … I believe it is because I am a poor Indian. I Can’t help that God has made me So; I did not make my self So.” When a neighbouring white schoolmaster, Robert Clelland, tried to seize some of Occom’s lands, Occom responded with fury:

Take Care that you don’t turn your Self out of Heaven—… you represent me to be the Vilest Creature in Mohegan; I own I am bad enough, and too bad, Yet I am Heartily glad that I am not that old Robert Clelland, his Sins won’t be Charged to me. … I am, Sir, Just What you Please, S. Occom.

This sort of thing got him labelled a troublemaker. Eventually his stipend was stopped altogether.

He had one supporter, however: his old teacher Eleazar Wheelock, who now made a suggestion of his own. Wheelock’s Native American school was underfunded and dogged by accusations that he was using his pupils as forced labor. He hoped to reestablish it with a proper endowment. Occom agreed to travel to Britain to raise funds.

He was there from 1766 to 1768, and hated it. On its fact, the tour was a storming success: He raised some £13,000. But he bitterly missed his wife and family, and he did not much like his hosts, to whom he was merely “a Spectacle and a Gazing Stock.” British crowds wanted to gawp at him, not listen to him. And, like any good Puritan, he despised England’s bishops, who “don’t look like Gospel Bishops or ministers of Christ.” They gave him lukewarm encouragement and no money:

It seems to me that they are very indifferent whether the poor Indians go to Heaven or Hell. I can’t help my thoughts; and I am apt to think they don’t want the Indians to go to Heaven with them.

But he posed for crowds and bit his tongue.

When he finally returned home, his situation deteriorated further. In 1769 he was accused of drunkenness, which seems simply to have related to self-medicating after a shoulder injury, but given the stereotype of Native American alcoholism, this accusation was lethal. Wheelock now took the opportunity to drop his fundraiser. When he established his new institution, Dartmouth College, with Occom’s funds, it rapidly became clear that this was not going to be a missionary school but just another college for wealthy young white men.

Occom’s sense of betrayal was complete. In a volcanic letter to Wheelock, he wrote:

Your Seminary … is already adorned up too much like the Popish Virgin Mary. … Your College has too much Worldly Grandeur for the Poor Indians; they’ll never have much benefit of it.

Like a fool, he said, he had believed Wheelock’s promises, left his young family, crossed the ocean, and humiliated himself for months on end in pursuit of a missionary dream. “Now I am afraid, we shall be Deemed as Liars and Deceivers.” He recalled a conversation he had with the great evangelical preacher George Whitefield before he left England:

Ah, says he, you have been a fine Tool to get Money for them, but when you get home, t hey won’t Regard you, they’ll Set you adrift.—I am ready to believe it Now.

Occom and Wheelock had a final meeting, but all Occom could do was tell his former mentor he would answer before God for his deceit.

And yet Occom was unbowed. He continued ministering. A sermon he preached at an execution in 1772 became a bestseller, going through 19 editions. No Native American writer had ever achieved anything like that kind of success, and it made him a sought-after celebrity preacher. He used his fame to establish a new, pantribal Native American Christian community named Brothertown in upstate New York, where a neighbouring minister believed that “there is no Indian … who has more inveterate prejudices against white people than Mr. Occom.” In fact, Occom could also be unsparing about his own people’s failings, but it is true that he would not wink at white folks’ sins, in particular at slavery. He never kept anyone in slavery himself, insisting that those who did so “are no Christians; they are unbelievers.”

So his story is one of prejudice, defeat, and betrayal; but also of Puritan virtues: righteous anger and mulish persistence. And the legacy he left is deep. The Brothertown Indian Nation that he forged in the wake of the American Revolution relocated to Wisconsin in the 1830s and survives as a thousands-strong community down to the present, despite being denied formal federal recognition. Occom would recognize both that community’s ongoing struggles and its stubborn endurance.

David Brainerd’s case is very different. He was the 18th century’s most celebrated missionary to Native Americans—and another staunch predestinarian—but at the heart of his much-told story is a mystery that enables us to see his ministry, and with it missionary Puritanism more widely, in a different light.

When Brainerd died in 1747, aged 29, he had spent less than four years as a missionary, first at the forks of the Delaware River in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and then at Crossweeksung, New Jersey. Until the final year of his mission, he admitted he had not “had any considerable appearance of special Success”—that is, his ministry had been outwardly almost fruitless. He was certainly fervently committed to “the enlightening and conversion of the poor Heathen,” but he was already gravely ill with tuberculosis and prey to weeks-long bouts of debilitating spiritual anxiety and depression. He was also, naturally, entirely dependent on interpreters. When he moved to Crossweeksung in June 1745, he was “exceedingly depressed with a View of the Unsuccessfulness of my Labours,” believed himself to be a worthless burden to his sponsors, and considered resigning.

And then something remarkable happened. He preached to the seven or eight Native Americans living near his new base. The next day, they asked him to preach again. “None made any Objection, as Indians in other Places have usually done.” After three days, his congregation was nearly 30 strong; a week or two later, 40. Some began to show signs of being struck to the heart by his message. Brainerd was sure this awakening would soon subside, but it only strengthened. Barely a month after arriving, he baptized his first converts. Many more followed over the next year. On August 8, “the Power of God seemed to descend upon the Assembly like a rushing mighty Wind. … They were almost universally praying and crying for Mercy in every Part of the House. … A surprising Day of God’s Power.”

Surprising indeed, but naturally Brainerd’s admirers have had no desire to explain the mystery. The glory of this awakening lies in its very improbability. If this solitary, sickly, depressive minister showed no previous signs of being able to kindle such flames, that simply demonstrates that God’s Spirit was at work through him. Which may be true, but there is another solution hiding in plain sight: Brainerd had just changed his interpreter.

The man’s name was Moses Tunda Tatamy—a name Brainerd mentioned only once, amid several references to him simply as “my Interpreter.” Tatamy first catches our eye because he and his wife were the first two converts baptized in July 1745. Brainerd had first hired him because of his linguistic skills, but initially worried that “he seemed to have little or no Impression of Religion upon his Mind, and in that Respect was very unfit for his Work. … I laboured under great disadvantages in addressing the Indians, for want of his having an experimental, as well as more doctrinal Acquaintance with divine Truths.”

And yet, over the winter of 1744–1775, Tatamy was “somewhat awakened” by Brainerd’s preaching. Brainerd was initially skeptical about this conversion, but what convinced him was the change in his work as Brainerd’s interpreter when they came to Crossweeksung:

There was a surprising Alteration in his public Performances. He now addressed the Indians with admirable Fervency, and scarce knew when to leave off: And sometimes when I had concluded my Discourse, and was returning homeward, he would tarry behind to repeat and inculcate what had been spoken.

Tatamy is a constant, understated presence throughout Brainerd’s account of the awakening. The converts “were much assisted by my Interpreter, who was with them Day and Night.” Tatamy informed Brainerd of who was “under Concern’ and who had “received Comfort” before accompanying him to counsel them individually. When Brainerd himself traveled, he worried that the fervor would fade in his absence and praised God on his return to find it had not, for Tatamy had been there the whole time. By contrast, in September 1745, fresh from the revival, Brainerd visited another nation, on the Susquehannah river; but his preaching there fell on stony ground. Tatamy did not speak their language.

Tatamy is a constant, understated presence throughout Brainerd’s account of the awakening.

Brainerd openly, if not quite fully, recognized Tatamy’s contribution. Preaching through an interpreter was generally a poor business, but thanks to Tatamy’s “sense of divine Things,” Brainerd believed his sermons had lost nothing “of the Power or Pungency with which they were made.” He also knew that Tatamy was not merely translating:

He was rendered capable of understanding and communicating, without mistakes, the Intent and Meaning of my Discourses, and that without being confined strictly and obliged to interpret verbatim. … When I was … enabled to speak with more than common Freedom, Fervency and Power, under a lively and affecting Sense of divine Things, he was usually affected in the same Manner almost instantly.

This was not Brainerd’s mission. It was his and Tatamy’s—or perhaps Tatamy’s and his. At least it was until Brainerd’s posthumous hagiographers wrote the interpreter out of the story.

Brainerd went on to early death and great posthumous fame. Tatamy, nearly 30 years his senior, lived until 1760 and became a preacher in his own right, as did his son after him, but has largely vanished into obscurity. He is mostly remembered now for a dispute over lands he purchased and that, later, Delaware Indians tried in vain to reclaim. There is a borough named after him in eastern Pennsylvania and a swamp named after him in the New Jersey town where Orson Welles set his infamous radio version of The War of the Worlds.

The point of Tatamy’s story is not simply to rescue a remarkable figure from obscurity. Cases like his and Samson Occom’s show that missionary Puritanism cannot be separated from its context of ethnic conflict, prejudice, and dispossession. But they also show it cannot be reduced to that context. Puritanism was capable of going beyond the naive and condescending talk of “allurement” and fostering a Native American Christianity that could put down roots even in the harshest of circumstances. That alone might be seen as, as the title of Brainerd’s memoir called it, “a remarkable work of grace.”