In the debates between Roman Catholics and Protestants (such as they abide), the former have the advantage of a worship service that ends generally in an hour and features a rite that combines both mystery and communal feeling (the Eucharist). For their part, Protestants on the lower side of the high-church-to-low-church spectrum limp along with a service that, to finish in an hour, needs the pastor to preach for no more than 30 minutes. If Protestants add the Lord’s Supper to the ordinary service, worshiping cooks who have forgotten that this was the week for the sacrament will invariably be worrying about the roast in the oven at home, which is to be ready for consumption when the family has heard a sermon, had a cup of coffee, and set the dining room table. In fact, if the Bible matters to the liturgy debates between the two parties of western Christianity, Protestants are hard pressed to understand how the Eucharist takes center stage in other Christian traditions when the New Testament is so explicit about preaching in direct instruction and examples.

If the sermon remains the heart of much Protestant worship today, you have the Puritans to thank.

Scripture does provide some instruction on the Lord’s Supper, but the New Testament is far more explicit—as counterintuitive as it seems to modern outlooks—about the value and effectiveness of long-winded men speaking. In the so-called Great Commission, Jesus told the apostles to make disciples by teaching (he also mentions baptism). In Paul’s instruction to his pastoral apprentice, Timothy, the apostle emphasizes the logocentrism for which Protestants are known (and sometimes dismissed): “I charge you in the presence of God and of Christ Jesus, who is to judge the living and the dead, and by his appearing and his kingdom: preach the word; be ready in season and out of season; reprove, rebuke, and exhort, with complete patience and teaching” (2 Tim. 4:1–2). Then there is the example of Peter early in the book of Acts, who on the very day of Pentecost marked its significance apparently not with the ceremony that resembled Christ’s meal with his closest disciples on the night when he was betrayed. Instead, Peter “lifted up his voice and addressed” the assembled throng. He preached a sermon.

Among the Protestants best known for taking this part of biblical precedent seriously, the Puritans remain noteworthy. A label often misunderstood—H.L. Mencken once defined Puritanism as “the haunting fear that someone somewhere may be happy”—the Puritans were a wing of English Protestants that sought further reform (or purity) of the Church of England. Their calls for greater fidelity to Scripture and their study of the early church coincided with Elizabeth I’s religious policies designed to steer both England and her established church through conflicts downwind from the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Dissatisfaction with both Elizabeth and her Stuart successors eventually prompted some Puritans to strike out on their own in a colony across the Atlantic in North America. Unshackled by bishops and crown officials, New England’s Puritans attempted a holy commonwealth. The prospect of running their own colonies, first in Massachusetts and then in Connecticut, also gave Puritan ministers the opportunity to institute worship services free from the taint of compromise.

At the heart and center of the Puritan worship service was the sermon. Anglicans at the time, at least in London, were also preaching long sermons—John Donne’s were supposed to last an hour or more—but those verbal filet mignons (as opposed to word salads) came packaged in the liturgical forms of the Book of Common Prayer. Puritans kicked away state-church liturgies, prescribed prayers, vestments, and requirements for worshipers to kneel or make the sign of the cross, and gave wide berth to the sermon, which, according to Harry S. Stout in The New England Soul: Preaching and Religious Culture in Colonial New England, was “the only regular medium of public communication,” “the central ritual of social order and control.” Not only was the Puritan sermon the public rite that bound the community together, but it was also the chief occupation of New England pastors. Stout adds that “twice on Sunday and often once during the week, every minister … delivered sermons lasting between one and two hours.” He calculates that, over the course of the colonial period (1630–1763), ministers delivered five million separate sermons to a population that never exceeded 500,000. Those numbers indicate that the average churchgoer in New England heard roughly 7,000 sermons over the course of his or her life. That meant listening to a sermon for a total of 15,000 hours (or almost two years of a person’s life). Talk about overcooked pot roast.

To observe that Protestants do not preach like that anymore is not simply a question of quantity but also one of erudition, because the Puritan sermon was a remarkable display of rhetorical skill. On the one hand, ministers were beneficiaries of a classical education that exposed them to the importance of grammar and rhetoric in verbal communication. This led to the use of metaphors that would appeal to hearers. Because church members were not familiar with the classical authors and ancient Greek and Latin texts, Puritans refrained from using classical allusions in sermons. They did, however, purposefully employ metaphors not simply fitted to the social experience of church members but that also influenced the separate faculties of the soul—the will, imagination, affections, and understanding. Successful sermons needed to involve all the faculties. Puritan preaching included illustrations from both Scripture and common experience. As a sea-faring people, Puritans were prompted to use maritime imagery. Such language was not as prominent as using types and shadows from the Old Testament to point to Christ as the fulfillment of salvation history.

Puritan knowledge (and use) of the Old Testament drew upon Reformed Protestantism’s highly elaborate covenant theology. The Reformation principle of sola scriptura invited close scrutiny of all Scripture, which in turn launched intricate interpretations of the covenants that God established with humans, from the covenant of works in the Garden of Eden to the covenant of grace that proceeds from Abraham and Moses to David and Jesus as the mediator of a “new” phase in the history of redemption. As much as covenant theology could lead Puritans to imagine themselves the New Israel with attendant obligations for personal and national obedience that could lapse into moralism, this theological grid also added another layer to the depth of Puritan intellectual achievement. Not only were Puritans well trained in the regular arts curriculum, but to stay conversant with their peers, pastors needed to give careful scrutiny to both Scripture and systematic theology.

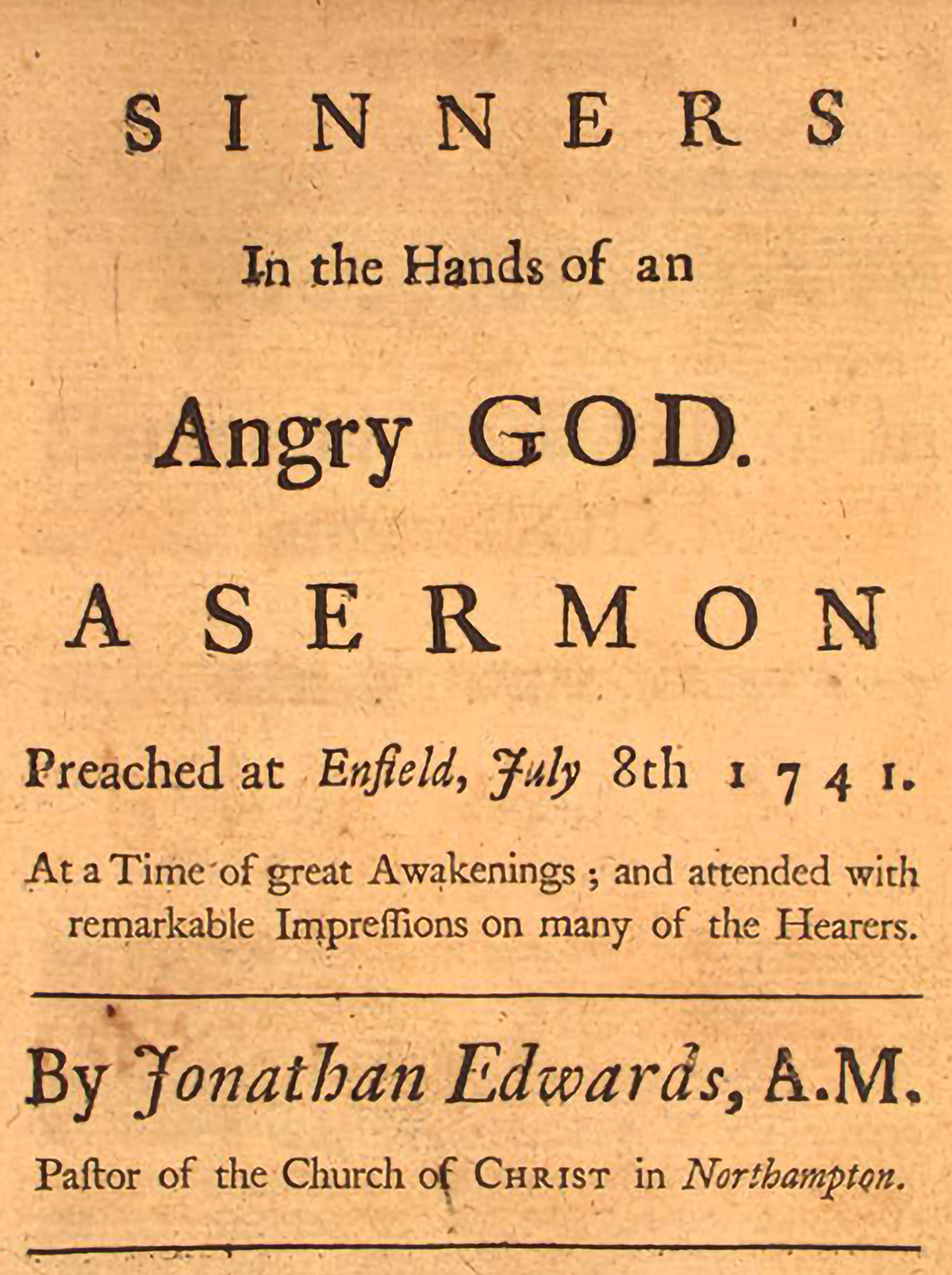

One of the most famous Puritan sermons on American shores is Jonathan Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Born in 1703 (East Windsor, Connecticut), Edwards was several generations removed from New England pastors who cultivated the standards and style of Puritan preaching. Some even argue that by Edwards’ time, the ideals of and hopes for Puritanism of the early 17th century had failed. However someone comes down on that point, Edwards’ sermons demonstrate all the habits of Puritan preaching. “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” included in most anthologies of American literature, follows the standard order of a Puritan sermon: text, doctrine, reasons, and application. In this case, Edwards’ text was Deuteronomy 32:35: “Their foot shall slide in due time.” His doctrine was the sure destruction of sinners owing to their wickedness and unbelief, and that the only circumstance keeping persons “out of hell” was the “meer [sic] pleasure of God.” From there, Edwards developed reasons for 25 paragraphs, all to support the assertion that “natural men are held in the hand of God over the pit of hell; they have deserved the fiery pit, and are already sentenced to it.” Even more dramatic, perhaps, was Edwards’ additional comment that “the devil is waiting for them, hell is gaping for them, the flames gather and flash about them, and would fain lay hold of them, and swallow them up.” The most famous part of the sermon came in the application, when Edwards employed the imagery of a spider, though his claims about God may strike moderns as more provocative:

The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider or some loathsome insect, over the fire, abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked; his wrath towards you burns like fire; he looks upon you as worthy of nothing else, but to be cast into the fire; … you are ten thousand times more abominable in his eyes than the most hateful venomous serpent is in yours.

As Cara Ball argues, Edwards’ sermon became famous not for the doctrines he explains but for its “sustained imagery.” He employed so many images and made their realities so immediate that listeners “were left with no escape.” Ball adds that what has impressed literary scholars is “the sermon’s raw immediacy, intensely personal tone, escalating emotional appeal, syllogistic structure and pulsating rhythm.” Yet “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” exhibits the sort of learning, theology, and attention to Scripture that characterizes Puritan sermons generally, even as it stands out among them.

When surveying Puritans in New England, Jonathan Edwards receives the lion’s share of attention (in England, he does not rank as high as Richard Baxter, John Owen, and Thomas Manton). Still, because Puritans excelled at preaching, the ranks of gifted pastors even in North America extend well beyond Edwards, who came at the tail end of Puritanism in its most vigorous expression. Among American Puritans, Samuel Willard, Urian Oakes, and Thomas Hooker—all 17th-century figures—stand out as skilled exemplars of Puritan preaching in the New World.

Puritan knowledge (and use) of the Old Testament drew upon Reformed Protestantism’s highly elaborate covenant theology.

Samuel Willard (1640–1707) was born in Concord and trained for the ministry at Harvard College. His first call was to a church in Groton, a town roughly 25 miles northwest of Boston, then on the border between English settlements and Native American territories. In 1676, hostilities between the colonists and natives forced the town to scatter, at which point Willard received a call to Old South Church in Boston, where he ministered until his death. (He was also vice president of Harvard for the last six years of his life.)

Willard’s funeral sermon for John Hull, Esq., on Psalm 116:15, “The High Esteem which God Hath of the Death of His Saints,” mixed Puritan zeal and communal compassion. He reminded his congregation that the deceased’s status as a saint was more important than family relations or friendship. “That they were Saints … makes their loss to be greater than any other Relation doth or can.” Others’ tears are natural, but when a saint dies, he “deserves the tears of Israel.” Although all praise for the deceased’s accomplishments would fade compared to a life of faith in Christ, Willard acknowledged the significance of death in human terms. Boston’s government had lost a magistrate, the town a benefactor, the church an “honourable member,” his family a husband and father. Despite all these accomplishments, “this outshines them all: that he was a Saint upon Earth; that he lived like a Saint here and died the precious Death of a Saint, and now is gone to rest with the Saints in glory.”

Urian Oakes (1631–1681) spanned the worlds of 17th-century Puritanism. Born in England, as a baby he accompanied his parents to Massachusetts Bay and eventually graduated from Harvard. In 1654 he returned to England only to be ejected in 1662 from his pulpit, thanks to the religious policies of Charles II. Back in North America, he was a pastor in Cambridge before presiding over Harvard for the last five years of his life. His 1677 Election Day sermon, “The Sovereign Efficacy of Divine Providence,” based on Isaiah 41:14–15, was a reminder that for many Puritans the Protestant work ethic was never separate from God’s control of all affairs. “In him we live and move, and have our being,” Oakes explained. The counsels of civil magistrates, “how rational soever,” would “not prosper” without God’s blessing. The same went for pastors, “how sufficient soever, pious, learned, industrious, [and] zealous.” They could convert or edify no man without God. Even in battle, training was in vain “unless the Lord bless.” He added that “when valiant Souldiers come to fight; whatever Skill, and Strength, and Courage, and Conduct, and Advantages they have, yet they will be worsted, if the Lord do not give Success.” Oakes did not say that human striving is pointless. Human agency was indeed valuable. But in the overall scheme of earthly affairs, the success of a proper use of human ability depended on God’s sovereign plan.

As much as Puritans looked to God for succor in distress and acknowledged dependence on God’s ultimate and hidden purposes, they did not neglect the interior life, as Thomas Hooker proved in his preaching. Born in 1586, Hooker came to America after Archbishop William Laud forced him out of the ministry. Hooker first pastored in Newtown, Massachusetts, before relocating in 1636 to Hartford, where he became the dominant figure in the Hartford colony’s brief history. His 1656 sermon “The application of redemption by the effectual work of the word, and spirit of Christ,” based on 1 Peter 1:18, is a reminder that Edwards was not unusual in describing the effects of sin. On the one hand, Hooker explained that sin’s heinousness stemmed from its jostling “the Almighty out of the Throne of his Glorious Sovereignty” by placing the sinner’s will above the divine. On the other hand, Hooker was not reluctant to use the consequences of sin to scare his auditors. The enormity of sin made plausible that a “Terrible God” punished “a poor insolent worm” and sent him “packing to the pitt.” Hooker could heap it on, such as when he declared, “Suppose thou heardest the Devils roaring, and sawest Hell gaping, and flames of everlasting burnings flashing before thine eyes; it’s certain it were better for thee to be cast into those inconceivable torments than to commit the least sine against the Lord.”

And yet Hooker was not all fire and brimstone. His counsel against sin came in one of his books, Application of Redemption (1656), where he correlated the effectiveness of preaching. Hooker drove home the point that Christians needed constantly to examine themselves. The ministry of the word was ineffectual among sinners. Instead, God “drives the sinner to sad thoughts of heart, and makes him keep an audit in his soul by serious meditation, and pondering his waies” before “working kindly” through the preaching of the word.

As intellectually challenging and as heavily doctrinal as Puritan sermons could be (especially by contemporary standards), preaching was not merely a way for pastors to show off. Many historians have argued that the care Puritans devoted to their sermons stemmed directly from pastoral care for the cure of souls. David D. Hall, one of the greatest American historians of Puritanism, highlights the simple reality of Puritan (and Reformed) piety, namely, that preaching was “the chief means of grace.” The best way to attend to the health of church members’ souls was by preaching sermons that were both accurate in their presentation of biblical truth and that took Scripture teaching from bare abstraction to immediate appeals to the hearts (or faculties) of believers.

Although Puritans did not subscribe to the Second Helvetic Confession, their high estimate of preaching was akin to the first chapter of the Zurich church’s statement of faith (1566). Because Scripture was the source of “true wisdom and godliness, the reformation and government of churches,” preaching the word “is the word of God.” “Wherefore when this Word of God is now preached in the church by preachers lawfully called, we believe that the very Word of God is proclaimed, and received by the faithful.” Even if the pastor were “evil and a sinner,” the word preached “remains still true and good.” Again, the Puritans themselves did not necessarily affirm this Swiss confession, but English Puritans were in the vicinity of it when they wrote in the Westminster Shorter Catechism that the Spirit made “the reading but especially the preaching of the Word” an effectual means of salvation.

Although Puritans did not subscribe to the Second Helvetic Confession, their high estimate of preaching was akin to the first chapter of the Zurich church’s statement of faith (1566). Because Scripture was the source of “true wisdom and godliness, the reformation and government of churches,” preaching the word “is the word of God.” “Wherefore when this Word of God is now preached in the church by preachers lawfully called, we believe that the very Word of God is proclaimed, and received by the faithful.” Even if the pastor were “evil and a sinner,” the word preached “remains still true and good.” Again, the Puritans themselves did not necessarily affirm this Swiss confession, but English Puritans were in the vicinity of it when they wrote in the Westminster Shorter Catechism that the Spirit made “the reading but especially the preaching of the Word” an effectual means of salvation.

Of course, Protestants reduced the western church’s sacraments from seven to two—baptism and the Lord’s Supper—and did not conceive of preaching as a sacrament. But the effect of the early Protestant estimate of preaching was to endow the words of the pastor during worship services on the Sabbath with a meaning and function that resembled Roman Catholics’ high regard for the Mass. The legacy of Puritan preaching is still discernible in contemporary Protestant worship. As much as the liturgy of praise bands and Hawaiian-shirt-wearing megachurch pastors has reduced Protestant worship to 30 minutes of singing and 30 minutes of speaking, preaching remains a defining characteristic of Protestant expectations for worship services. Contemporary sermons may seem more like TED talks than deep dives into Scripture. Acquaintance with theology and rhetoric may be far removed from distracting illustrations and lame attempts at humor. But Protestant leaders of churches and the people who go to them still expect a longish period of instruction based on some part of the Bible. If today’s Protestants do not compare favorably with the Puritans, the tradition of preaching that those English Protestants in both Old and New England developed remains strangely alive.